“There’s a lesson to be learned from this and I’ve learned it oh so well,” was coming out of any number of small radio speakers when we marched across the perimeter and into the temporary encampment Captain Casey referred to as his command post. I walked in the lead with the Gunny behind me, feeling like, but not resembling, the much taller and hugely more elegant leader of the Marine Corps band. The music wasn’t marching music, and I somehow felt the part of the song playing about a mythical non-existent red rubber ball might prayerfully apply: “I’ve bought my ticket with my tears, and that’s all I’m going to spend.”

The captain had somehow offloaded some version of real shelter from the chopper, and set it up in the very middle of the open area of the sand covered river bank. As I approached, it looked like nothing more than a bullseye in the middle of a large target.

I looked back over my shoulder. The company followed in the first semblance of any kind of order I’d seen since dropping into its midst so few days before. The Marines did not march to cadence or with the parade ground precision the corps was known for all over the planet. But they walked with order, their loads shifting, machine gun belts swinging and bodies leaning forward into the task of moving heavily loads. I checked my Omega, and the little hand was on the three. There was plenty of daylight left, which meant plenty of time to get off of the exposed open area and safely set up in inside the brush and under the hanging eave provided by the near base of the cliff we’d just descended. I knew instantly upon seeing it that the flat sand bank was a killing zone.

I tried to straighten myself up, as our tattered and dried mud mess of a company snaked out onto the packed sand clearing. Captain Casey waved the side of his tent-like structure aside and stepped out, with Billings behind him. Both men were angry about something, from the expressions on their faces. Red Rubber ball finished playing from behind me on Fusner’s radio. I stopped when the Gunny, off and just back of my left side, touched my elbow.

“Company, halt,” he ordered loudly and unnecessarily, using a deep D.I. guttural growl. The silence and sudden stillness was filled with Brother John’s deep comforting voice. Brother John didn’t normally comment that much between songs, so I was vaguely surprised as I tried to meet Casey’s and Billing’s baleful stares. “It’s fixing to be an interesting afternoon in Vietnam,” Brother John said, but he got no farther.

“Turn that God damned thing off,” Casey screamed at the top of his lungs, before breathing deeply in and out to get control of himself.

Fusner fumbled and got the transistor radio shut down.

“Who in the hell do you think you are, Lawrence of Arabia?” Casey said, his voice deep, and filled with a seething anger.

I looked away from his accusing eyes downward. My eyes focused on his feet. He and Billings were wearing their new jungle-issue oil-soaked green socks, but no boots. I looked away, past Casey’s tent toward the turgidly moving brownish waters of the nearby river.

“No, sir,” I replied, formally. I had automatically assumed a position of attention in reporting to my commanding officer but was having trouble holding it because I was so tired. My thigh muscles ached from the climb down, and the rest of my body felt like a beaten piece of meat from the fearful tension that hurt all the time. Strangely, it also seemed to hold me together like some form of biological epoxy.

“He’s Junior of Vietnam,” I heard come whispering gently from someone behind me.

“Who said that?” Casey screamed again. “There will be no more radios turned on while I’m commanding officer of this company. Anyone violating that order will go on report or be demoted on the spot.”

Casey breathed deeply some more, while everyone waited. I had nothing to say and still had no idea why the captain was mad. My eyes focused on a slight movement from the cliff side of the tent. Rittenhouse poked his head out. I stared into his eyes. He immediately looked down at his clipboard and appeared to make notes about something.

“Mudville,” Captain Casey hissed out. “You think I’m deaf? You think I’m not up on the command net? You think I didn’t go to school? “Mighty Casey strikes out? You think that’s funny?”

I physically rocked back at every verbal broadside he launched at me. His emphasis was so harsh and driven with slight delays between each sentence, that I was shocked. I wondered how I’d created so much enmity in such a short period of time? I also realized that I wasn’t afraid. Not of Casey or Billings.

“We need to break down the tent and get off this open area,” I replied. “They have 82-millimeter mortars down here waiting, I’m sure.” I looked quickly all around us. “Maybe not while the suns still up, but later for sure.”

Casey leaned forward, bending slightly at the waist, before standing up straight again, his facial features smoother and not giving any more emotion away.

“It can’t be you,” he finally said, softly, ignoring what I’d said about the real danger of imminent attack. “You’ve been here less than two weeks, Rittenhouse tells me. There’s got to be a darker force at work here opposing my command. A more experienced evil force.”

I moved my head slightly until I could see the side of the Gunny’s face from the corner of my left eye. I watched his eyes get bigger but he made no move to say anything or react in any other way. He didn’t look back at me, although I was sure he’d seen my glance.

“Where’s that black sergeant?” Casey asked, suddenly. “Sugar, whatever. I want him up here now.”

“Sugar Daddy, front, and center,” screamed the Gunny over his shoulder.

This time the Gunny met my eyes, and I wasn’t surprised to see a slight smile cross his lips. Sugar Daddy came lumbering up from the back,

wearing his usual flat bush hat and horrid purple sunglasses. His two Marine flunkies flanked him.

“I asked for the sergeant, not you idiots,” Casey said, pointing at the two Marines, who promptly turned and ran back into the mass of the company.

Sugar Daddy sidled over next to the Gunny’s left side. “Sir, reporting as ordered, sir,” he said, the sing-song words rolling out with about as much sincerity as a man trying to entice a dog to come forward with a snack of raw meat in his hand.

“I’m not going to take any more nonsense from you, and the resistance I’m getting from the rest of these Marines,” Casey said, pointing his finger at Sugar Daddy’s chest. “I know what’s going on. The Gunny’s going to supervise your every move from now on until I can get a real platoon commander to take over. You make one false move and your ass belongs to me.”

Sugar Daddy was about to reply but couldn’t because the Gunny had hit him in the side so hard with his left elbow that the wind had been knocked from his lungs.

“I’ll get right on it, sir,” the Gunny said. “There’ll be no more of that Mudville kind of stuff. I’m gonna be all over him.”

I looked back and forth from the Gunny to Captain Casey and wondered just where I was. The A Shau valley had been touted to me as the most dangerous place in all of Vietnam but no one had mentioned that it might also be an alternative form of the known universe or some kind of fantasyland.

“You’re dismissed, sergeant,” the Gunny ordered loudly, using his D.I. command voice.

Sugar Daddy pulled his sunglasses off and then turned to trundle back to the company. His eyes caught mine as he went around. A look of befuddled shock was in them, with his forehead wrinkled up in question. I knew from experience that the killing anger would come later.

I turned my gaze back to Rittenhouse, looking up from his clipboard at the scene. The Gunny had willingly thrown Sugar Daddy under the bus, but I knew he hadn’t been the one to point the black sergeant out, as the evil force in the company. That had been someone else. Someone close to Casey. Rittenhouse looked away again, a move I was getting used to. I hunted for Jurgens, who had to be somewhere on the perimeter he’d set up to ‘protect’ the command post. Jurgens and his men were experienced and seasoned enough to not be stupidly exposed out on the sand surface like they’d left the captain and lieutenant.

Nguyen’s face appeared from the brush, only a few feet from where the edge of the sand encountered the jungle growth. He looked back at me and and then looked along the line of bushes we marched past. I followed his gaze. Jurgens stood out of the line of my sight, unless I turned my head to the right. I could only glance over at him. This time he wasn’t laughing or even smiling. My look must have signaled my intent. Jurgens was a bit of vermin that needed to be dealt with very soon. His glance met mine with equal malevolent intent. I’d not forgotten the conversation he’d had with his men when I was nearby, so many days ago. The die had been cast, but I hadn’t really understood that at the time. I did now.

“About your boots,” I said to the captain, trying to bring the subject back to the dangers of having long conversations on top of a mortar registration mark.

“I want the corpsmen, all of them,” Casey said, looking briefly down at his feet. “There’s some sort of foot infection going around in this company. I’m sure someone must have seen it before. Billings and I can barely walk.”

I thought about the chopper ride both men had commandeered from the LZ above down to where we were. Maybe the captain had a point in doing that. If he thought he couldn’t walk the distance, then it all made sense. I was beginning to feel sorry for the man.

“And I don’t know what in hell you’re doing with this screwed up unit lieutenant,” he said to me. “You’re not the company commander. You’re the forward observer, and that’s it. You don’t have any plans. I have plans. I make and approve plans. Do you hear me? Do you understand?”

“I’m trying to keep you alive,” I blurted out, regretting the words as soon as I uttered them.

“I’ll keep myself alive,” Casey said, calmly, having regained some kind of emotional control of himself. “Billings and I will do just fine as long as you and the Gunny do your jobs. We inherited this mess from the previous company commander, and that would be you. We didn’t create it. You did nothing to fix the Sugar Daddy mess and now I have to. And I’m God damned tired of calling that man Sugar Daddy. I want his full name.”

“I’ll get that for you immediately, sir,” Rittenhouse said softly from behind him.

I stared at the scene in front of me. The captain stood in front of a tent that might have come out of some thirties African safari movie, set up in the very center of an obvious enemy target area, in his stocking feet almost unable to walk while talking to the company about how he was the leader and they were just going to have to do what he said. My comment had been the truth but, in review, I also saw that I wasn’t going to be able to manage to save his life. I couldn’t even save my own life, except for the last few days, only because of the hand of God or blind luck.

Four loud and distinct “thups” echoed back and around the sunken area of the sandbank.

“Incoming,” shouts came in from all over.

I raced forward and grabbed the captain by his new jungle utility blouse. I dragged him, hopping and staggering, across the sand to the edge of the jungle near where Nguyen’s head had appeared. I punched both of us into the harsh sharpness of the wet leaves, bamboo and fern morass, stumbling over old downed branches not washed away in past floods. We hit the rough mat of broken painful foliage together, me on my right side and him on his back.

“About twenty seconds left,” I whispered into the eerie silence. I pressed down into the mess of vegetative matter, covering the back of my neck with my hands. I’d never received mortar fire before but I was terrified because of how close we had to still be to where the rounds were likely to impact. The only good thing about mortars was the extended flight time between hearing a launch until the round arced high, and then returned to earth. The seconds passed. I thought about the injustice of being in the field and getting hit every damned night, although this time it was before the night even came. I’d heard four distinct ‘thups.’ I waited for the four explosions that had to come.

The four came in, one after another, seemingly faster than the ‘thups’ had been when the rounds were launched from the tubes. It wasn’t like receiving artillery shells. The rounds only weighed in at about six pounds, instead of forty-five. The earth did not shake and debris was not tossed about to land like a great fiery rain of potential death, as had happened up atop the cliff. And then it was over. I let go of the captain and moved to a sitting position.

“I guess you were right,” Casey said, trying to get up and brushing himself off at the same time. “Like I said, you know your artillery.”

“That wasn’t artillery and no, you never said I knew my artillery, sir.”

The captain staggered to his feet, righted himself and departed back out onto the surface of the hard sand without further comment. I followed, with Nguyen appearing near my elbow. He looked at me quizzically and I read the message in his expression. If we went back on to the sand, then there would be more mortar fire to follow. I wondered in the back of my mind if there were marks on the surface of the sand like the ones he’d found up on the rock surface above. I increased my pace to a run.

The scene in the center of the sand would have been funny in an Oliver and Hardy film, because the tent had not been knocked down by a direct hit. Instead, the canvas had been torn into strips that blew about in the mild wind sweeping down from further up in the valley. Two corpsmen worked on a body lying on the bottom remains of the tent. Dread overcame me, as I approached, hoping against hope it wasn’t Fusner or the Gunny. Fusner had not followed my move to rush Casey out of harm’s way. He’d gone in a different direction. The call of “incoming” was always greeted with a fair bit of panic, so everyone had run everywhere to find cover.

“Pull up the canvas and get him off the target,” I said, wondering when we’d hear the sounds of mortars being launched again.

“You heard Junior,” the Gunny chimed in, leaning into what was left of the inside of the tent.

“No need,” one of the corpsmen said, “he’s gone.”

“Into the bush,” I ordered both corpsmen. I didn’t have to look. I knew who it was. Billings had dived into the tent for protection instead of running for the cover of the jungle. His body was there, but I knew it wasn’t shaped the way it was supposed to be shaped.

Casey stood behind me, looking down at his executive officer, saying nothing. The corpsmen moved off, pulling the I.V. they’d started and wrapping it up as they went. I took Casey by one arm and began walking him toward the jungle we’d come out of. The Gunny followed.

“We’re going to need more officers,” Casey said, his voice muffled and low.

“Yes, sir,” I responded, guiding him to the trunk of a large tree about twenty feet into the bracken. I helped him seat himself on the back side of the trunk for maximum cover. Pilson appeared out of the jungle to join him.

“Down,” the Gunny yelled, his order coming less than a second following another mortar launch.

I plunged to the jungle mat once more, face down, my mind unable to get the image of Billings’ torn apart body out. I closed my eyes. It was only one round. This time I knew from placing the sound of the launch that it had come from somewhere upriver. The explosion was no surprise, in either timing, amount of sound or where it struck, which was almost exactly where the others had come down only a few minutes earlier. One round, following four, meant that two things were occurring. The first was that the enemy didn’t have an observer nearby, so the mortar itself was probably a mile or less away. The second was that the mortar team didn’t have much ammo or the second volley would have been greater than the first, and it would have included some adjustment around the registration point to maximize casualties. None of that had happened.

I stood up and moved to the edge of the clearing. The remains of the tent canvas smoked, but there was no more damage that could be done to Billings that mattered. I turned to look at Fusner. The rest of the team had found him and gathered around and down, waiting for more fire. I crunched and slushed through the bracken to my pack and retrieved my binoculars, before turning around.

I stood at the edge of the sand clearing and stared up along the river. Both banks of the slowly moving water were about four or five feet high, and fairly flat. Low jungle growth covered these ‘plateaus’ of land until the areas began to ease upward toward the canyon walls. The left, or east, canyon wall was a long distance away, that section of land climbing up all the way to an escarpment. Beyond that everything else was covered with huge trees and isolated giant boulders along the way. I pulled out my map. The fire had to come from that area. Either we sent a couple of squad or platoon-sized patrols in that direction to drive the mortar team back or attack it. But there was no way to tell if that enemy mortar team was attached to a major military unit or not. We did not have the strength to back up a patrol in trouble, unless Kilo and Mike companies were headed upriver behind us.

I went back to Captain Casey and asked him about the movement of the other companies in the battalion, but it was useless.

The man had to recover. Battalion was not going to tell us where the other companies were unless we needed support because we were under attack. We’d been attacked but it was over, at least for the time being. I called Americal at Cunningham on the arty net.

After a short discussion, I knew the call was fruitless when it came to putting down artillery on any target. There was no target. Even though Cunningham had the capability to use high angle fire to reach many parts of the lower valley it did not have the ammunition assets to blindly zone fire up and down an area the size of Cleveland.

“What about air?” the Cunningham battery X-O asked.

My mind immediately went to Cowboy. If he was somewhere around in his Skyraider then he might be able to see fairly well through the lower thinner parts of the jungle.

“What’s up there right now?” I asked, hoping the X-O knew something I didn’t.

“There’s a gunship rotating out of Hue airfield looking for work I heard,” he answered. “Give me your position and I’ll fill him in so he doesn’t dust you.”

I read out our real position, repeating it twice. We’d lost Billings, our second officer in twenty-four hours, and I hadn’t checked or heard yet if anybody else had been hit by the mortar fire.

“Okay,” the X-O said. “I reached him. You can come up on the air net and he should be around in about half an hour. He said he’ll cruise down the valley toward your position, do a flyover, and then look for targets of opportunity upriver from you. He goes by the call sign Beowulf.”

I went to Fusner and had him bring the air radio up, although there was no traffic on it.

The Gunny was down by the side of a bamboo stand, having cleared a small area with his E-Tool and brewing a canteen holder of coffee.

I joined him, although passed on the inhaling from his already lit cigarette.

“What was in those boots?” I asked him, “because it sure as hell wasn’t oil.”

“Mosquito repellant,” he replied, in a tone like everyone put repellant in their boots. “Makes the sensitive wet skin form boils after a few days. Used by some of the guys in trying to get shipped to the rear.”

I heard a propeller airplane in the distance before my water was hot. I tossed the water, and put my canteen outfit back together. “Gunship coming in,” I said. “We take any other casualties?”

“Only the useless lieutenant,” the Gunny replied, blowing smoke into the bamboo stand to watch it rise among the stalks.

His tone was hard and calloused, which I expected, but also didn’t in some way. Billings had been useless but he’d also not been given a chance, like Keating. I couldn’t figure out why the Gunny had given me a chance, and I wasn’t going to ask.

The light was beginning to go when the plane came flying over. It was a big supply plane, the kind that flew in and out of airports all the way from the states. What help it was going to be I could not figure out.

All of a sudden some of the Marines were running into the flat sand area that had been mortared. They were waving and yelling up at the plane as it flew over. The plane waggled its wings twice, then banked steeply, and flew back over a bit lower, before heading upriver.

I called up Beowulf on the air radio, feeling strange. What kind of radio name was Beowulf? The man who replied indicated that they had some activity about a mile upriver and in toward the far escarpment.

I didn’t know what to reply except “Roger.” The man in the plane was another southerner with a heavy accent. He’d referred to the company as “you boys down there,” in the most drawling of accents.

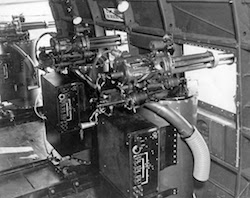

The Douglas AC-47 Spooky (also nicknamed “Puff, the Magic Dragon”) was the first in a series of gunships developed by the United States Air Force during the Vietnam War. More firepower than could be provided by light and medium ground-attack aircraft was thought to be needed in some situations when ground forces called for close air support.

I watched the big plane bank and begin to slowly turn toward the embankment. The side of the plane suddenly lit up, and a huge tongue of fire spit out from the side. The tongue lashed down, and then seemed to gently sweep back and forth over the jungle below. The roar that followed was like nothing I’d ever heard before. Like a trumpet section of an orchestra combined with that of an approaching train. It was wonderful and horrible at the same time. The tongue of fire continued to sweep around and down for half a minute before the plane abruptly pulled up and banked back toward the way it’d come.

“A little quiet in your valley down there, boys,” the aircraft voice said.

“What in hell was that?” I whispered to Fusner.

“That’s why the guys were all yelling and cheering,” Fusner replied. “Everyone loves Puff, but at the same time they want to make sure it never shoots at them.”

“Puff?” I asked, having heard the name vaguely.

“Puff the Magic Dragon, like in the song,” Fusner said, laughing. “Only the second time I’ve seen it. You never forget. I wonder what it’s like down there where all those rotary machine gun rounds went. Thousands and thousands of them. You can only see the tracer rounds, as the dragon spits fire, and tracers are only one in five rounds, of those fired.”

I walked back over to the bamboo stand the Gunny was still crouched under.

He’d pulled out another cigarette and was lighting it. I stopped to finish a thought. I finally got it about Beowulf being Puff’s call sign. It was the dragon thing.

“Quite something, that Puff, eh?” he smiled.

I wondered if I would ever be able to disassociate the gunship with the song, if I lived long enough to hear the song back in the real world.

“Find somebody to clean out the captain’s boots, and he’ll need some new socks too,” I said, looking twenty feet away, where the company commander still sat with his back against the tree trunk as Pilson, Jurgens and Rittenhouse gathered at his side.

“He’s an FNG shithead,” I said, taking a single puff from his offered cigarette, “but he’s our FNG shithead.”

Jim, couple suggestions for easier reading, Welcome home. Dave.

As I approached, it looked () nothing more than a bullseye in the middle of a large target. => add (like)

… here the company commander still sat with his back against the tree trunk as Pilson, Jurgens and Rittenhouse gathered by at his side. => by at, either word could be deleted.

Corrected, thanks

Semper fi,

Jim

That is what you get out of this story. A chance to edit someone’s writing?

Matthew,

We always appreciate reader input and Dave has been very helpful.

Semper fi

Jim

I’ve read three or maybe its five ,six story’s now, not sure how long I past by the site before I tried reading first couple I never finished , to much flooding my mind , Oh my the things I did not realize I remembered ,unnerving for a few days but I was curious so forced myself to read some more glad I did ,thanks and keep up the good righting Bro.

Thank you Bill, for working at it. I just lay it out day by day and night by night.

I have no plan or goal here other than to simply tell the story within parameters

as close to reality as it was. My wife corrects me sometimes because she’s heard bits

and pieces over the years. She reads the first draft and then says, “hey, that’s

not the way it was!” I pay attention and try to figure out what I told her and what I

am thinking in writing the story. Thanks for that work you are doing to absorb all this.

Makes me think it’s not just an old vet blathering away for free beers.

Semper fi,

Jim

“He’s an FNG shithead,” I said, taking a single puff from his offered cigarette, “but he’s our FNG shithead.”

With that comment, it seems to me that you “Became” a leader/commander. I look forward to watching how “Casey” grows or fails.

Thanks for this read.

P.s. I guessed correctly on the “mosquito boot dressing”. A stunt I knew nothing about until reading “The first 10 days”

The Gunny knew all about that stuff. How anyone ever figured out that putting

repellant in boots formed lesions and boils I have no idea, or why it did.

Stuff out there is discovered that boggles your mind back in the ‘real’ world.

Thanks for your conclusions, your comments and your support..

Semper fi,

Jim

Outstanding as usual! Had Puff work out for us. A few times, insane firepower. A POW told us they were told to lean into the rounds to avoid being hit 😀 Guess that didn’t work out so well. S/F

Puff wasn’t infallible because of the canopy. But man did it lay down the rounds

and scare the shit out of everyone even if they weren’t inside the beaten zone.

Thanks for the straight shooting comment and your support here…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jeurgens had to know the Captain’s tent was in a bad spot. Intentional?

Jurgens was real special when it came to

playing the game. Almost a match for the Gunny, but not

quite, thank God! Thanks for noticing and thanks for coming on here to say something.

Semper fi,

Jim

I’ve written you before; as always, great writing. That clip of Peter,Paul and Mary reminded me, so thought I’d share a YouTube video of them in a 2005 Christmas concert.

https://youtu.be/Qu_rItLPTXc

Thanks for the link Ed!!! Love that song to this day. Don’t know why

I really love it so as I should be one t shy away from it. But my roots run

deep back to the Nam and back to the corps. And Puff. And all of that.

Semper fi,

Jim

Each new chapter is as good or better than the next. It is raw and pungent and I can’t wait for the next chapter. I was in Nha Trang in 1965, a REMF but I don’t miss it. I have lots of respect for you grunts. We had the LRPs training there and the 5th SF was also there. You bring to life the blood and bullshit the grunts endured. Keep them coming.

Thanks Douglas. I shall be working on the next segment today.

Thanks for the encouragement.

Semper fi,

Jim

First of all, I will own this book, and share it with my family, all readers. As a son of a Vietnam Vet, and having been in a later conflict, I am awed not only by this story, but by all the people who have written in with their comments. You all are really awesome people, and so eloquent, more than I could hope to be. The book is truly great, but I also read the comments with real respect and complete interest!

I could not agree more about the comments and I stay up at night

to answer them…because the quality and the intent of the writers simply

demand to be recognized. I don’t know how to thank them and you except to

continue on with story…

Semper fi,

Jim

I find it remarkable that a Captain in the Usmc could be given command of a company and have nothing but shit for brains. You would think he’d of had previous experience as a platoon commander first. It’s a shame pitching that tent was a teffiffic market as you noted, damn near baited them into firing you up in the day time, a shame a man was killed because neither had any experience or common sense. The more I read the less faith I have in the USMC, I always thought we had out shit together, sounds like I’m wrong. I mean bug juice in his boots ? Great job as always.

The Marine Corps does have its shit together. It did back then too.

You will note that the enemy did not fare very well against us.

That we had internal problems goes without saying here. But some units

got hung out to dry. Not the fault of the corps. The good leaders cannot be

everywhere. The battalion commander was bad. And there you go.

thanks for the comment and the reading, of course.

Semper fi,

Jim

When you were coming down the cliff did you see any enemy bodies that fell down it? When i read the comments it is with wet eyes.gonna make it harder to shake a hand. I didn’t know until your accouts of how much of the battles happened at night. I spent a year reading about the Paris peace talks and after a year all they had decided was the seating arrangement. It pissed me off so bad I thought everyone concerned should be drug out and have a bullit in the head. My wife worked in a ordinance plant building primers for bombs. She lost a real good friend to a land mine and was part of the ones that sent baked goods over

I share all the episodes hoping it will help someone, will buy some books when they come out.

Can’t thank you enough, on behalf of a lot of the guys out here and there.

It was a strange time that caused a gaping alienation to be wedged in between

some really decent people back home and the guys and gals they sent out

there to protect them. thanks for caring and reading and comment about it here.

Semper fi,

Jim

I remember reading a novel about this in high school. The name was “The Gooney Bird” by William C. Anderson

Yes, I believe that was a short novel about the C-130 but I don’t really recall

that well. Thanks for that tidbit though.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, I was in in 68 – 70 but by the grace of God stationed in Ft. Riley, KS for all but a three month war game trip to Germany. I was given a choice when I got to KS w/a Nike Hercules tech MOS of infantry or MP. So after my visit to Germany I spent the rest of my time dealing with the souls returning from Nam to finish out their time in KS. They were good men, some of them were messed up mentally and others on drugs, I did what I could to keep them from being discharged before their time was up, even if they all hated me once they learned I was an MP. Nam was the first conflict (never a declared war) to be run by the Politicians and screwed royally. Much as Iraq was when Obama pulled everyone out and let it slip into Radical Islam. Bless You My Brothers

Presidents and upper members of the Military seldom get this jobs because of

past performance and many lead us into wars without any war experience whatever.

But they think they know. Common human trait. The only inexperienced ‘think’ comment

I ever really understood I never heard: “I think I know I’m dead.” Forget questions

I needed men who knew how to listen. Hard to find in combat and back here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Early on, Puff and DUSTOFF were about the only aircraft in the air at night. came to our aid more than once by strafing enemy areas as we attempted rescue of injuried troops.

Magic dragon provided as much psychological lift as it did destruction to enemy positions.

You’ll hear from Puff again as this saga goes on…

Semper fi,

Jim

I saw spooky a few times at AnLoc and Quan Loi. His call sign at An Loc was “Big Daddy” and ours was “Tarzan Cages”. I remember him dropping the parachute flares and how the shadows moved as the flares swung back and forth.Seeing the enemy in that moving lite was particularly unnerving. I saw some parking lot lites years ago that had the same orange color and it sparked memories.

Hated those parachutes swings. They made the enemy, when you did see them,

sort of super human. Agree with you entirely.

Thanks for that truth that could only come from bitter experience.

Flares in combat don’t work, or didn’t, worth a damn.

Semper fi,

Jim

we were spared three time from the enemy because of Puff, a very welcome sight never to be forgotten, tracer rounds were a steady flow streaming down on a large target, needless to say we never had another issue from the enemy again in each area they hit, it was always a pleasure to see them arrive in the evening sky, Gary a Puchett 7th ENG, BAT 1st Marine Div, Heavy G, USMC

Thanks for the comment and the experience with Puff. You own is a lot like

the rest of ours. I have never had one comment that didn’t say good things about that weapon of war.

You too. Me too.

Semper fi,

Jim

Love your story, Jim. I was not a grunt, but an Army engineer. Was in VN 3/71-1/72 on a company compound 60 m NE of Long Binh. For more than a month we were surrounded by 2 BN’s of NVA. Every night arty was dropped around us (105’s & 155’s) from FB Nancy 3 miles away, alternating with Spooky gunships. I try to describe the Spooky’s firepower to people, but if you haven’t seen it, you can’t really grasp it. Keep up the good work-can’t wait to get the book! Jeff Snyder, C Co, 169 Eng Bn, FSB “Rock”, ’71.

Thanks Jeff, sounds like supporting fires saved a few more, including you.

Impressive stuff. The A Shau was such a shithole because of confusing geography,

long range guns in Laos and the limits of our own supporting fires especially when they

were ARVN units (artillery). Thanks for the comments and liking the story.

Semper fi,

Jim

Can’t tell you how much I enjoy your writing! Thank You and keep it coming!

Thank you Jerry. Can’t tell you how much I enjoy getting the comments from one and all on here.

Thanks for taking that moment to write…and liking the work.

Semper fi,

Jim

” Attention all aircraft, this is Ramrod on Guard….avoid WR 2168 for the next 05 Mikes…..Ramrod out ”

In the cockpit there was mad scrambling on the ” one over the world” to find the Arclight impact grid……we could unass the area pronto, but I can’t imagine being on the ground anywhere near the impact area and not being able to move…

Abiding respect,

Bill

Naval Gun Fire from the Jersey and those arc lights

when we moved up toward the DMZ. Frightful.

But at least they were our own.

Semper fi, and thanks for that view from up there in the air…

and those heartfelt concerns about us down below.

Not discussed much.

Had to be a big worry though…

Semper fi,

Jim

” Attention all aircraft, this is Ramrod on Guard….avoid WR 2168 for the next 05 Mikes…..Ramrod out ”

This brings back a memory of my first tour as a crew chief on a slick, and Just how insidious that MF Murphy could be in murdering you, Yes I was sitting behind the gun as we were cursing out to Snuffy a FSB up on the Cambodian boarder, I was looking out checking the airspace around the bird, Making sure no other aircraft were approaching, no one was shooting at us, Keeping track of where we were, cross checking the instruments against the pilots, and getting nervous…. Something was missing, “The constant call from various out going fire missions on Guard…” I look back out to the 3 o’clock and saw strings of dots above us far out to the south east…… More and more strings appearing…. Then it hit me, I hit the intercom switch and screamed at Kiwi the AC if we had Guard Up, he looked down at the radio panel and started to say yes, When all of a sudden his hand jabbed down, and started turning a dial…. I head some static, and all of a sudden there it was …… Ramrod …. and a “ATTENTION ALL AIRCRAFT! AVOIDE 11°02′15.3″N 106°00′35″E”……… The Pilot was a new guy, and when he set the radio freq’s that morning he misdialed GUARD by 3 points, So there we were, flying along fat dumb and happy, bit a care in the world with strings of 750’s coming our way, and Murphy laughing his ass off, as we un-assed the AO…. No, You never want to fly formation with 750’s it does god awful things to the digestive system and mind…

Yes, FNG and Murphy……..

Wow! And thanks for that revealing portion of your own rough and tough

time in the Nam. And the reality of the radio talk, codes and other bizarre

stuff we learned in quick time…or died. Thanks for sharing that

It don’t mean nuthin’ As you understand with some others on here…

Semper fi

Jim

Enjoy reading your story of being over there with overzealous Capt. from the rear area. I was at Kham Duc (68) and watched Puff/Spooky giving us needed support. NVA had the camp surrounded and was slowly destroying vital areas of the camp with mortar and fifty cal. from surrounding hills after overrunning the hilltops during the night. Sunday morning we were given orders to get on the next available plane after destroying our radio equipment. Glad to see Chu Lai airbase and somewhat secure area . Arc Light scheduled to hit Kham Duc soon after all American and popular Forces were clear of the area.

The NVA had a hell of a time and could not have lasted. Our resolve

died back home before that happened though. War. Not fought so

much on the battlefield although lot of us lived and died there.

Thanks for the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

How right you are in stating that we lost our resolve back stateside. You should have said that Congress lost the resolve to win that war. They had all kinds of bravado when it came to sending our troops into that nightmare.

However, when the Pentagon wanted to end that war by bombing Hanoi, it was an entirely different story. Had they bombed Hanoi from the start, that war would not have lasted a year, if that! We would not have lost over 58,000 troops and brought home thousands of casualties which this government ignored.

Finally, you would not have a sordid story to write about, when it comes to the stupidity of politicians.

Well, J, I hope you didn’t really mean ‘sordid’ when it comes to my telling of the story.

I read the definition of that word and don’t really want to be even close to what it means.

But you are correct in that the DMZ destroyed everything because it gave them never

ending resupply. And so it went. Even with that we’d have still ‘won’ if we had been

allowed to persevere. But what would we have won? And entire population that didn’t like

us or want us there?

Semper fi and thanks for that comment.

Jim

My use of sordid applies primarily on how we got drawn into that war, the way thousands of young men were sent there to die for political purposes and then our troops forced to come home in disgrace. If that is not ignoble, I don’t know what else to call it.

By the way, I lived along side many of the South Vietnamese people, who loved having our presence there to fight for their freedom from communism. They were caught between a rock and a hard spot, because most knew that if the North was not defeated, they would lose what freedom they had. They were right too, as the U.S. politicians bailed on them, just like they did on our troops.

In no way am I condemning you for writing about the truth, so no defense is necessary on your part!

Thank you J. I was sort of struck by that word, but I get your drift.

There was no justice, no clue of anthropological understanding of the region or it’s peoples.

There could have been no win that could have been called any such thing.

It is hard, almost impossible, to install democracy where poverty is extreme and there’s no

basic education system that can inform and teach the masses.

Communism is so easy…going in, and deadly when it takes hold.

Thanks for bothering to explain and being here in the first place.

Semper fi,

Jim

I have been reading your accounts , bring back those things that never really never go away to the forefront . I was in country 3 Aug 67 to 30 Aug 68. Spent a few weeks in Da Nang ,then Phu-Bai-Hue , with HMM-163. Last duty station in country was Quang-tri , about 1 mile north of the city ,it was know as Base-X ,my squadron helped the C-Bees build it. We did most of the insertions an extractions in the area from about Oct./Nov.’67.,then they move in a Huey and 46 squadrons.If you ever saw the old UH-34’s ,( piston helo),that was us. I did many runs to re-supply an evac. in Ashua ,welcome home Brother.We got rockets/ motars /cannon fire dropped on us. Your fight was meaner than ours . Thanks for the read. Russ.

Not necessarily meaner Russel, depending on what of that shit you discuss fell on you!

It was all about not getting hit. Getting hit in a modern war is damn near getting dead.

Roll the dice. It don’t mean nuthin’

Semper fi, brother in the air…

Jim

Thanks for the come back. Forgot to say we were the 34’s with the eyeballs on the engine cover, we called them bastard eyes , the officers called them evil eyes .

Loved those bastard eyes. As you know I kind of identify more with the enlisted

side than the officer side in all of this. Leading is a very delicate thing

and so many officers think they know about that and the come in and get a whole

lot of people dead while they learn the reality.

Thanks for the comment and for the support.

Semper fi,

Jim

Got to watch Spooky a couple of times at night. The guns were about a klick away. Grinding growling red death flowing… Hard to adequately describe. Maybe it had something to do with heavy wet Delta air, but I swear I could feel the vibration. It was crazy-awesome.

What an orchestra of fire it was. I so remember. I never saw one

of those ships up close. I’d love to go to an airshow and see what was in

them but there’s probably none left around.

Thanks for the comment and liking the story…

Semper fi,

Jim

There was an AC-47 some years ago at the Air Force Armament Museum near Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. It has three miniguns mounted to fire to port and lots of machine guns as well if I recall correctly. I saw it when I visited there while on a business trip related to the modern version, the AC-130H, which has a howitzer as well as a minigun and a rotary cannon.

You are accurate in what you are writing about here.

The three mini-were what our 130’s had, although I think we also had the old

C-47s up there too. It was tough to get them though because the competition was

that way. Many times over there when you were getting hit others around you were

getting hit too.

Semper fi,

Jim

Puff would cover a grid square “QUICK ” … SAVED many Marines during Operation Scotland. ..I was amazed at the firepower. ..almost felt sorry for Charles. …OoooooRrrrrrrrrAaaaaaaaah!

I share your ambivalence when it came to that. I admired the enemy in all forms

but hated him too. I wanted to get back home so bad I could not help but hate all of them,

but I’m better now.

Semper fi,

Jim

One thing I experienced was the shaking of the earth while b52s were doing their thing. I was sitting on a track and the vibration was something else. Also puff did his thing for us when we sprung an ambush. Luckily we were able to call them in.

Thank you Walter. Funny how so many of us can identify with one another based

upon the weapons we were around and so effected by.

Thanks for the comment and the knowledge…

Semper fi,

Jim

LT have you ever read Sand In The Wind by Robert Roth?

Yes, Tony. Class act of a book and a great writer.

thanks for mentioning it here and commenting..

Semper fi,

Jim

Fusner’s second time seeing puff needs a quotation mark, and the heavy packs from heavily as your company marched up, if I may be so bold, and I am assuming all made it down without casualties. Yes it is real enough for worry. Rittenhouse is a fact-checker with an inability to lie. I can almost feel his pain, and Casey’s wrath is embarrassing to him. I don’t know why I share this compassion for Rittenhouse? Maybe because he is caught like a rat in a trap with his own leaders, while everyone else gets options.

As usual, an in depth analysis from a master. You should have been a detective!

More to follow and I can say much about what you said, although I much enjoyed reading it.

Semper fi, brother,

Jim

Jim you have opened so many dark areas of my life I don’t know if it’s good or bad. I do know that the VA doesn’t have anyone that could open those dark areas the way that you have thanks. watched puff do its thing and it did save many lives alot of things I would like to talk about but can’t find the words to say it. I think the capt. killed the lt. for setting up where he did. keep up the good work thanks Dave

There was stupidly abysmal decisions made in combat by so many.

Including me. Things like what the Captain did are now forgivable for me

although I thought he was horrid and endangering us all. Did he get

Billings killed? Yes and no. When the mortars went off none of us grabbed him

and got him out of there like the Captain. Fault is a tough one.

Thanks for the interesting comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another great read Jim! If you don’t mind I’d like to ask you about a response you made to a comment earlier. About the guy in the bunker in An Hoa. I had to go to the rear for a day or two don’t remember why. I noticed little glassine vials on the ground. They were about an inch and a half long and the greenish color of an old Coke bottle. When I asked someone about them they said they were heroin vials. They said you could also get pre rolled pot in cigarette packs. Someone put a lot of time and effort into making this stuff. I often wondered who. Guess I need to watch that movie Air America. Do you think it’s factual? I was there in 69/70 and I saw the vials in Bien Hoa. Thanks Jim! God Bless Puff

I don’t know. When you are mostly in the field in combat all you get

are rumors and what you yourself experience. I never saw the vials or had trouble

with heroin that I knew of.

There seemed to be plenty of pot to smoke and I ignored it (mostly by the black Marines).

Did not seem to effect much at the time.

Nobody was ever seriously fucked up from drugs unless it was from morphine.

There was Tiger Piss beer smuggled in somehow but rare. T

here was beer dropped from choppers on one occasion

but only about enough for one can per Marine.

There was that awful ‘wine’ our Montagnard would get somehow.

Dead rat or something at the bottom of it and tasted that way too.

I tried it once and got sick. No, I didn’t get evacuated either.

Thanks for the question.

Semper fi,

Jim

C co 1//5, road duty outside An Hoa, half way to Liberty Bridge, bought a machine rolled joint. A buddy and I shared the joint, the FNG didn’t, he stayed awake and I had the best sleep ever!!! Just about one of the stupidest things I did in VN.

You made it brother. It don’t mean nuthin’ Not now.

Anyway, a good nights sleep probably got you through a couple

of days you might not have otherwise lived through. Thanks for more of

the truth we get on here and almost nowhere else.

Semper fi,

Jim

James-As soon as I see your new episode, I have to drop everything and read it through. Can’t wait to buy your book. I was not a grunt, I was a deuce and a half and jeep driver for a medical company in Long Binh and Phu Loi in 65-66.

Your writing paints a great picture of the bad stuff you heroes went through. Thanks for your service, welcome home!

Don

There were no heroes out there that I met. We struggled mightily undner burdens

not meant for young humans to carry. We cared for one another when it suited us

or killed everyone around us upon occasion, by accident and by design. ‘Hero’ one day

and goat the next…I suppose. Situation ethics prevailed over all…

Thanks for bringing that up.

Semper fi,

Jim

Every day now, I ask myself whether enough time has passed that a new installment will be posted. This is a gripping tale. Cannot wait to read the next part……Bob

Working on it right this second Bob, just as soon as I get done with responding to

your comment. Lots of comments these days but then, I have a lot of spare time.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great story. For me a catharsis of hidden horrors.

Many REF came through my AID Station for medical supplies when they ” volunteered” to participate in an A Shau op in order to get their CIB’s. My medics and I couldn’t believe that is why they did that. We got our CMB’s not by choice but because the 101st operated there. FYI lots of pot was purposely laced with H. I found many of those vials mixed in with catches of captured meds. Welcome home !!!

Steve, 101 st ’68-9.

Really interesting stuff here doc. You have a few stories to tell, as well.

You are no doubt right, although most of my Marines were functional at all times

unless they were choosing not to be. I understand drugs better now, given that

the terror was so unendurably deep and heatless.

And we were kids, of course.

Thanks for the contribution.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was always amazed at how thoroughly torn up the area of impact was after “Snoopy” worked it over. ALL we ever found were blood trails. Definitely put the fear of fire power in the knuckleheads.

Interesting and we will go into some of this in the coming segments.

After action and all that entailed. The real and the not so real.

Almost always awful though.

Semper fi,

Jim

Yes, You are well ahead of the curve, When is Casey going to wake up dead? How did he ever make Captain? Even the fuck you lizards had more sense.

I am waiting to see how You end up dealing with Jurgens, He is one of the main focal points of the trouble within the unit, You or Gunny are going to have to make another run on him, Now Sugar Daddy, It would seem He is developing a respect for you and your abilities, But I wouldn’t really trust him with your back, and Rittenhouse, Now there is a piece of work, Why hasn’t he fallen to sleep on a live frag? That is a weasel of there ever was one, Yes never up front, But always ready to sink his fangs in you heel, Trying get himself enough brownie points to get out of the field, always sucking up….. Yep, I see Casey killing himself with his own stupidity, Jurgens well, You will have to turn that bastard in the night loose or He will murder you, and Rittenhouse, You need to move him into the line, and let the beast take care of him, The beast is always looking for a snack.

What a line! The beast is always looking for a snack. I have to work that in Robert. Too cool

And it was so true. It was like the night monster from the closet when I was a kid was

back and waiting. For me, so I kept throwing him snacks and getting by.

Shit, great analysis and spot on too.

Some of you guys impress the hell out of me. I am not as smart as I think I am!

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, You are plenty smart and a quick study, or we wouldn’t be having this conversation, The only thing that is a problem in Murphy, and from what I have read, Yes, He shows up in your future, Murphy The Mother Fucker, Throwing snake eyes in the game…… I would be proud to have you on my team anything Semper fi!/This We Defend!

Thanks Robert. I think that would be some team. Back here I’ve been a bit of

a success in the wild variety of jobs I’ve been fired from (23). Didn’t get fired from the

corps, just mustered out. Thanks for welcoming me back!

Semper fi,

Jim

OK, let’s get something straight here, when I read the comments from your brothers I get the combat smart part. Maybe you shouldn’t lower yourself but, rather, allow them up to your level. So far as I’m concerned, if you got out of the shit you’re all pretty damn smart.

Well Hell Walt, I didn’t understand any of that. Once more please!

Semper fi,

Jim

I’m just answering the comments as best I can. I don’t have a any style I’m aware of…

LT, no need to reply. Used to be a proofreader/editor. Here are some

corrections, and I’m going to go back over all chapters of “The Second Ten Days” and look for more. Takes 3-4 readings before I can back away from the story enough to notice errors! (I’m rusty, so I might miss a few)

Paragraph: The captain had somehow offloaded some version of real shelter from the chopper, and set it up in the very middle of the open area of the sand covered river bank. As I approached, it looked nothing more or less like than a bullseye in the middle of a large target.

Correction: It looked like nothing more than a bullseye

Paragraph: “I looked back over my shoulder.” Correction: Next sentence, take out the comma. Don’t need it.

Paragraph “This time the gunny met…” Correction: Space before the

sentence beginning with “Sugar Daddy…”

Paragraph: “Sugar Daddy was about to reply…” Correction: …knocked from his…”

Paragraph and Correction: “You’re dismissed, sergeant”, the Gunny ordered loudly, using his D.I. command voice.

Paragraph: “And I don’t know what…” Correction: observer

Paragraph: “I raced forward…” Correction: …me on my right side and him on his back.

Paragraph: “The Scene in the center…” Correction: “…on a body lying on the bottom…”

Paragraph: “I stood at the edge…” Correction: …to an escarpment. Beyond that everything was covered…

Paragraph that begins with “The man had to recover.” Correction: “it was over, at least for the time being.”

Paragraph “The Gunny was down by…” Correction: put a blank space in before the line “I joined him…”

Paragraph “Find somebody to clean…” Correction: Pilson, Jurgens and Rittenhouse gathered by his side…”

Got to say thanks Arnie. Made the corrections. Hard to catch some things and then these new computer programs

for word correct things that were not wrong in the first place! Sincere thanks.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another gem. Thanks Jim. When we got overrun (in an NDP with C 1/9, 3rd Marines) and had reestablished a perimeter of sorts, Spooky (C-130) came on station. We put ammo cans in front of our holes and lit C-4 in them to give them a read on our position. The light and sound show was unworldly. Another poster used the “rheeee” sound and that was accurate except the pitch was kind of low. Brrrrrrrrrrrrp was more like it. When we policed the battlefield in the morning, it was something else. Reduced an NVA battalion to hamburger. Will never forget that.

Definitely wanted Puff to know where you were. Great idea the boxes and the C-4 with maybe some jungle shit in there

for more smoke. and then burrow down@

Semper fi,

Jim

Really great story. Took me back to Pleiku in 67. I was in a combat Engineer Battalion, US Army. Keep up the good works.

Thanks Monte, I am on it. Writing on the plane tomorrow.

It’s always good to have some encouragement to keep going on a project that

is bound to piss a lot of people off.

Semper fi,

Jim

I spent a lot of time at night, sitting in a hole in a revetment wall, on guard duty. Often times, I would see Puff work out north and west of Da Nang. He would be close enough at times, that I could hear the awesome sound his guns made. I cannot imagine the fear it must have created in the guys on the receiving end of those rounds.

Thank you Jim for what you are doing. Semper Fi.

Hey Skeeter. Glad you had a hole. I had one some times. Loved

having a hole. Sometimes still dig one at the beach and the grand kids love it

but their parents think is unsafe because it’s so deep. they have no clue, of course.

Semper fi,]

Jim

I never personally experienced the power of gunship as a recon squad leader In Nam, but interestingly my son became a gunship pilot and flew a Viet Nam era AC130 H in a later war. The gunships continue to provide tremendous close air support to the ground troops and are much loved by the grunts.

Yes, I heard that they are still out there. Very popular like the A-10.

The stuff that can really reach down and help right then and there.

Like the Skyraider too.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim;

My Brother-in-law was in a Marine Corps infantry company in VN in 68/69. When he and I got out he would confide in me about some of the stuff that he had done and seen and I still remember our talks to this day. Because I have been reading your chapters from the start I could not wait for a chance to tell him about your work but with our busy lives we don’t get to see each other often. So out of the blue my sister calls and invites my wife and I out to dinner. As we travel in the car to the restaurant I begin to tell my brother-in-law about your book I have been reading on line. He acted like he was interested until I ask him if he ever heard of the A Shau Valley, A strange look came over him and he said as matter-of-factly “ yes I been there”. Then he wasn’t interested in talking about it anymore and I knew enough to change the subject. After almost fifty years I guess he has buried the memories deep. I would love to rehear the stories but I’ll not ask again.

Anyway Jim, sorry for going on so long. I read each chapter two or three times just to make sure I didn’t miss something.My wife is starting to wonder about mi II think.lol Awe-some work !

Sherm

He has not buried the memories. They travel with him through time and, in fact,

are the very waters that keep him afloat.

He has somehow been able to accommodate and get along.

I, and my work, are not here to disturb his journey.

You did what you could be there’s really no way to predict whether

such contemplation over the reading would be good or possibly emotionally destructive.

Thank you for trying to help him and also for attempting to see my work as curative in that process.

Thanks also for the sincere compliments and the

detail of your writing here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim,

Like the other guys, I think you have a great talent for writing. You do a great job of making the reader truly understand what you, and many others, went through in Vietnam. Hopefully your book will become a “must-read” Vietnam war classic.

As I commented earlier, I served in the Air Force as a radio and nav-aids tech Dec 65 – Mar 66 at Tan Son Nhut and April-Nov 66 at Pleiku, where I worked Puffs (AC47’s) and Skyraiders (A1E’s). The Puff’s had three side-firing electric gatling guns each of which could fire 6,000 rounds per minute. They also carried a bunch of million candle power parachute flares for lighting up the bad guys on night missions, which were most common. (To this day my key ring is the pull ring from one of those flares.) Most of the Puff’s were WWII vintage and older than many of their crew.

Both the Puff’s and the Skyraider’s primary role was ground support. A role I always thought I understood, but which you have brought to life in your writing.

Keep up the good work.

Ground support is better today, or so I’ve seen with some of the

onboard camera stuff on Apache helicopters. The Cobras were so great

and can’t imagine what it would have been like to have Apaches.

Thanks for the background, the compliments and the support.

Semper fi,

Jim

Lt thanks for waking up the echoes. When I saw Puff work out I was reminded of the neon lights of Vegas.After my tour I return to school managed to earn 2 degrees in nursing and spent 40 yrs in psychiatric nursing, 25 with the VA. Never met a psychiatrist, therapist worth a tinker’s damn! Didn’t think I had RVN issues till I met a Young Doc who started calling me Kowalski. I didn’t have a clue, he told me to watch the Clint Eastwood movie “Gran Tranio. Then the light went on! I am a casual Catholic and have neighbors who are Vietnamese Boat people escaped from Da Nang. I had a stroke due to effects of Agent Orange and the Vietnamese neighbors are always ready to help. Thank you for your book. I enlisted while in college rather than be drafted in the Army and a good life long childhood friend got drafted and put in the USMC. He’s in counseling at the VA and when you book is avaialable I will gift him a copy. Thank you, sir

It’s good to read your voice, so to speak. The different paths we ended up on as we came back. Those nights over

there, not just with our own actions but sometimes able to see and hear what was going on nearby, hoping it wasn’t contagious.

Your sojourn with VA counseling I understand. How could those guys and gals know if they didn’t go and the guys and gals who

went don’t get those educations or training or jobs. We are the ‘victims’ of war and god damn it everyone would be so much better

off if we just acted like it. We came home like the horses of the cavalry in the Civil War. Our hoofs unshod, our teeth worn and

not even given the opportunity to proudly pull a plow. But here we are, many of us standing still and unbent inside. It’s a pleasure to

read of so many of them and enjoy this strange comment relationship.

Semper fi,

Jim

We called the sound from the chopper miniguns “Elephant Farts”. Puff was just “Death From Above”. We were on a hill on the edge of the A Shau right where the Ho Chi Minh trail came into it,relaying comms from the valley to Div.Totally awesome writing.

You know the valley I know write of. I got asked on Facebook if I’d ever been there or

whether I was just writing away. I asked the guy if he’d ever been there. Then I asked him

if he though that the color and smell of that river sand down there was easy to discover on the Internet.

The color of those rocks and the endless foliage and animals. The rents in the walls and the tunnels dug into them.

That strange wind that seemed to run in the same direction and speed as the brownish water in that turgid river.

He hasn’t written back. The A Shau was even distinctive in Vietnam. It sure as hell was a long way from Buffalo New York

where I went in…

Thanks for the compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Sir, I continue to read your postings and it continues to bring. Ack memories. I too saw “Puff” work out one night. The guys in my unit said watch this. I saw 3 red lines coming from the sky. About the time the red lines stopped we heard what the previous post was like a continuos fart. I’ve heard the dinks drop them in the tubes also. I’ll never forget those sounds. Keep the articles coming and thanks again.

thanks fro the encouragement and your own view of the Puff application.

Haven’t heard the word ‘dink’ in a long long time!

Semper fi,

Jim

Had Puff help me out many times. Before I retired Worked with the AC-130 Spectre many times and wished I had that in Nam! My favorite was the F-4, it had this sound coming in on a strafing run that brought chills! When I was in the hospital in Japan ,on the way home,there was a F-4 crew chief that showed a hart with speed and angle of attack that explained the Banshee scream! Loved that rectangular area on the graph. Have to give a shout out to the great OV-10 Bronco too. Was a lifesaver. On my last tour my Dad was overhead in a B-52! Every letter ended,Please be accurate!

Didn’t get much Phantom support but did get some OV-10 help.

Later in the story. Thanks for the comment and reading the story.

Semper fi,

Jim

LT, your superb writing grabbed me from the start. You really transport the reader to be in your shoes and feel what you were feeling. I find myself anxiously awaiting your next episode. My hat is off to you and all those who found themselves there and having to face all sorts of situations that no man should wish on another. Your sentence: “Both men were angry about something, from the expressions on my face.” might need an edit (maybe their faces?). Have friends who served in country over there in various roles and returned home safely. I had 4 years of college in by June 1968 and had one more semester to go. For various reasons, decided to see marine recruiter and discuss volunteering for service and volunteering for Vietnam. Could complete my military service in a year and 9 months. Talked to him once more and needed to go back and sign papers. Fraternity brothers talked me out of it. Have always wondered what would have happened had I signed…but have nothing but the highest admiration for those who served. God bless you and all the rest, and thank you all for your service.

Thanks for that compliment WD and your own history. Yes, like would have changed for you

in dramatic ways. But you are also here today and maybe that’s because of your frat brothers

advice. Of course somebody has to go but those somebodies don’t have to come home and

wish that everyone they went for went. If that makes any sense.

Thanks for your comment and the compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

đại úy,

We didn’t have Puff. We had Snoopy or Spooky gunships. Loved ’em. Seemed like they could stay on station all night & drop those wonderful ” turn night into day” flares. When they cut loose with their mini guns, they brought piss & vinegar!! Hard to explain to non-grunts what it sounds like when they worked out. Not the “tat-tat-tat” you see & hear in the movies but more of a “Rheeeeeeeee” The long red snake of tracers, thousands of ricochets, the ground looks like someone used a meat tenderizer on it. Trees & brush mowed down. And that’s just one at a time. Never saw more than two at a time. Can’t imagine the hell three or four would bring.

Keep on keepin’ on & remember, “Don’t mean nothin!”

Bruce

2/14th Golden Dragons

25th Inf Div

’69 – ’70

Not likely to forget. Ever. Thanks for that rendition of Puff, the way you remember it.

Sort of the same for all of us who stood under and watched and heard.

Don’t mean nuthin’ is not understood out here on todays streets, of course.

Like to have the VA counselor explain it and then I’d laugh.

Had to live it…

Semper fi,

Jim

I remember Spooky – west of Da Nang hosing down the area around very steep mountain top just to the west of us. Said to be a French hunting lodge. Very impressive weapon. Very!

Thanks for commenting here Bill. Some really strange stuff they invented and used

there and amazing to see and hear.

Semper fi,

Jim

amazing…simply amazing. I know the mini’s on the huey I crewed were set up so the pilots could either fire one at a time or both. Either one by itself would fire 6000 rounds per minute. When firing both they would drop down to 3000 rpm each. My understanding was that 6000 was optimum. With our basic load we had enough for 1 minute of firing. The guns were limited to 3 second bursts. The ammo, direct from the cans came linked 4 ball to 1 tracer. All three of the hueys I crewed had the same setup; one minigun, seven rockets, and one door gun to each side. By 71 the C-47’s were history. AC 130’s had taken their place.

LaVoie. I have a friend who was L.T. Vanni back then who speaks of a laVoie from his PLC class

back in those days. I wonder if it is you. Thanks for being up on your ballistics shit. It’s better than

mine. Maybe I should research the internet better before I write the segments but I don’t. I just let er rip

as best I can and maybe apologize later when I’m wrong about something. We must have had some Hueys with rotary

but I only remember the M60s and a few Ma Deuces…

thanks for the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

i’m not Vietnam I enlisted in 1979 but my DI’s were I am proud pf what I learned from them I was in the Army SSG. I know if you do have the head space and timing on the ma deuce she won’t fire we had what you called Vulcans track mounted miniguns 7000 round per min. thanks for your stories I wait to read every day I heard a lot about the A-SHA VALLEY from my DI’S

Trained with the .50 and loved what little experience I had with it, only to

discover that they had them out there in the field and we did not.

We moved too much and they had those damned tunnels.

Ferocious weapon. Sure as hell glad they didn’t have rotary.

Semper fi,

Jim

no apologies necessary sir. I always got a kick from watching the movies where they fire off a mini with MG background noise! I was enlisted through and through so I would be very surprised if your buddy and I ever met. I rode in the back, usually in the left door manning a 60. We had tremendous latitude to use anything we desired, as long as we could make it work. Most of the guys I flew with stuck with the 60 since it could be carried if (when?) we became unintentional grunts. Every now and again we would run across a navy uh-1n, (twin engine huey) they usually had a mini in each door. I’m having a hard time staying calm while waiting on your next excerpt. Great writing, sir!

Thanks for the enthusiasm of this reply and the knowledge, as well.

Most of your life in the chopper was a mystery to those of us you served.

As you know, the choppers just did not stay around long enough to have social time or

make chatter. Back in the rear the air was totally separate from ground.

Thanks for sharing here and being ready for the next segment tomorrow.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great reaction LT. Casey sounds like the 4th CO I had, starts giving orders before knowing whats even going on in the bush. Once you’ve had “PUFF” work around you, you never forget. Keep them coming Jim, so many of us need this to help bring back the memories.

I wonder what kind of L.T. I’d have been if the Gunny hadn’t latched on to

me from the get go. If the Gunny had not been there. I’ll never know

whether I’d have been okay or a total asshole…before I died, of course.

I would not be here without the Gunny and I well know it.

thanks for the comment and the compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

A tent! Billings ran into a tent to get away from incoming? I am sorry he died, but how did he get to be a 1st LT in the Marines and not know more than that. He had to have heard you say that the open area would be a target. He should have known it without being told. Get behind something solid and get flatter than flat.

Puff came up and worked our western perimeter one night. I have these pictures that show this angry red stream of death seeking victims on the ground. I was glad I was two or three hundred yards away. Loud, very loud.

Enjoy Hawaii.

Thanks Joe. I will be writing out in Hawaii, because I have to finish another novel set there

and also work on these segments. I am going to meet a couple of guys from on here who will be there on the 19th.

I’m meeting them at the Kaneohe O’Club where they kind of know me so that ought to be fun.

The caption was a captain not a first. Training. At Quantico we were constantly being forced to spread out

when moving through the bush but the guys all tended to cluster, just like in combat. At Sill they were constantly trying

to keep our heads down when arty was danger close but the guys wanted to see the rounds go off.

It does not always work out that reason wins over other shit in combat zones.

Thanks for the observation. Never forget that some of us are better adapting in the field than others.

I did not understand that in Vietnam. Only years later in the CIA did I come to understand how I helped my

own survival by having that talent.

Thanks for the comment and if you send photos of Puff I’ll put them up.

Semper fi,

Jim

I has the pleasure of flying 2 CIA dudes. I wish I could’ve thrown them out of my Huey instead of the 2 Victor Charlie’s

The CIA was not had no ethical presence in Vietnam. Nobody has ever come forward

to deny what Mel Gibson portrayed in Air America and nobody attacked the producer over its making either.

There was a guarded wired compound at An Hoa and inside the bunker sat the man who controlled the drugs going in and

out of the airfield. That man’s name went all the way up to the White House. How the DEA, the CIA and even the FBI abroad

are ever going to shed their attachment to the lure of those huge caches of cash out there in the world is beyond me.

I never wanted to work with any of it but that does not mean you cannot be co-opted without your knowledge until it’s too late

or forced to work with them.

Thanks for the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Sent the pictures by messenger in Facebook.

Fucking “A” my friend!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

Another installment that I couldn’t stop reading until it was done. That Casey still hasn’t caught on at all yet. Wondering if he is even capable of it. I knew as soon as you asked about his boots and he wanted the corpsmen what the gunny had done. Then his setting up that tent like he is on a holiday trip in the center of that clearing I had to shake my head even though I haven’t been in combat. He don’t sound like he has enough mettle to recover and become useful even if Sugar Daddy and crew don’t frag his dumb ass.

On another note you mentioned early times and PTSD I had an uncle that was a Seabee in Korea. He operated a dozer and had to do mass graves. He came back and never put the bottle down. I also worked around a couple men from WW II that were called shell shocked. They would work normal for a few hours then something would set them into a daze and they would wander off to return later. It was more prevalent then most folks knew. Many were remanded to state hospitals and just hid away.

How do we accommodate those who come back. The American Indians used to form them into

a special council and have them meet together all the time to advise the leadership, and to be on

hand for the future when they might be needed…and then train the young ones coming up to be warriors.

Pretty damned good deal for everyone. The vets had a place where they were respected and not felt sorry for

like your vets. I don’t go to Memorial Day or Veteran’s day events because I do not want to be ‘honored’ which is merely

another substitute word for pity. I took drugs and drank to keep from killing people back here that damn well needed killing

even more than the men I killed. But I had to survive. I had to make it. And so I did. But not with help from my culture.

I cried in the parking lot outside the VA hospital in San Diego the first time I went in after I got out. They listened to my tale of

woe, it was January, and then gave me an appointment for ‘treatment’ the following June.

There’s still no system for us. There are not automatic jobs with prestige. There’s no money. There’s plenty of pity.

Fucking keep it. I’ll make it on my own.

Sorry to run on about that one, but I feel for the men reading this story, as they’ve come to identify themselves and I

know they just won’t say, can’t say what I’m saying here. And it that damned story.

Thanks for writing Peter and I appreciate the compliment at the start of your comment, as well.

Semper fi,

Jim

Only saw Puff or Spooky work out once one night,,,it was terrifying and awe inspiring at the same time,,,,there was this constant ragged sound of the firing,,,,and the tracers like a laser beam down to the ground,,,,and the bullets impacting the ground sounding like a herd of buffalo,,,,never saw an arc light but I would not want to be on the receiving end of either one….some good Officers and N.C.O.’s or Shake and Bakes or Nescafes and some bad ones,,,,amazing anyone survived Nam….

An Arc Light Strike was something else, mostly because the planes were too high to see

or hear on the ground. The strike zone just lit up and white shock waves blew out in all directions.

Then three was black smoke that wandered over the area for about an hour. Not a whole lot of guys

survived out in the field it they stayed there for any time. Remember that seventy percent of the entire

mass of sailors soldiers and Marines never went to the field, as such. So there are a lot of veterans of the war

but not many who survived out there in this killing jungles and vallies.

Thanks for the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thoroughly enjoying the read. Keep up the good work.

Thank you J.D., it’s always nice to have positive comments on here.

I read every one, like your own, and respond to every one…like your own…

to say thanks and I will persevered…

Semper fi,

Jim

As usual I get to the end too fast. A fast, riveting, soul clenching read. Keep up the good work. If your FNG shithead survives he might just turn into a decent leader…..

As a new guy LT, you’re doing a pretty good job in the field — as well as keeping us spellbound with your story.

A year ago, could you believe you’d grab so many of us and make us feel like a fish chasing the elusive bait? Looking forward to the comments and the rest….

I had no idea of the latent interest in this subject or in how popular this comment site would be.

Fortunately, I don’t have a real job so I can write the segments and respond to the comments.

Thanks for the compliment about the reading.

Semper fi,

Jim