Jurgens stood where he was, arms slightly outstretched, but he made no other move, his expression unreadable except for a faint tick arching his left eyebrow up slightly every few seconds.

“We are the same,” Jurgens said, splaying his fingers out, like his statement was more self-evident than any discussion might need to explain.

I didn’t move. I was perfectly relaxed. He blinked and then I blinked. Again, in a kind of hypnotic sympathy. We stood, ten feet apart. He had no weapon. His life was mine, and both of us knew it.

The drums. The drums that had only vibrated up from the valley once before, began to beat their deadly foretelling doom from the walls of the valley, skipping back and forth to reverberate in resonance with themselves. Jurgens and I were standing, while the team was down among the waist high foliage atop the sandy mud of the ever-moving river bed. We were exposed, and the drums were beating their message about that very fact for everyone to hear.

Jurgens slowly moved to his knees, only his half-raised arms, shoulders and head above the field of ferns that grew up from the sandy mix of loose-rooted foundations. I went to my knees with him, and lost the connection to his very being. It was gone. The moment was past. Jurgens was a future problem, once again.

The drums beat louder. We’d taken the fifty from them again. They’d taken Tex in return, but his loss was not enough. The jagged beating had nothing to do with music. There was no trilling syncopation, or rhythms and chords. The drums beat a message that was clear and possessive. The valley belonged to them, just as the vibrations filling the fetid air also filled our ears and our lungs.

I went flat to the floor of the jungle, and crawled my way back to where I’d dropped my binoculars. The company was gathering on the other side of river to make the crossing, while the Skyraiders screamed back in, so low their props blew tiny bits of jungle debris into the air with their passing. I rotated to see them hit the hillside again with their monster machine guns. They didn’t fire many rounds, since their loads of the heavy ammo were severely limited, but their presence and their deadly potential reminded anyone dug in on that hill that death was ever present and ready to claim any that might be identified or revealed.

I watched the company advance toward the tied-off end of the rope secured on the bank of the far side of the Bong Song. I slowly moved my binoculars where I didn’t want them to focus, until I could see the place beyond the tank where the river bent slightly west. Tex’s body lay face down, half out of the water. I worked the poorly designed focusing knobs with my muddy fingers. Tex’s head was on its left side, his face pointed downstream. His lower legs bobbed in a small eddy that rose and fell, raising his boots half out of the water and then back in again. I could see no wounds on his back or lower torso, or any damage to the part of his head that I could see.

But I knew the swirling water would have washed away almost any evidence as the round or rounds that hit him had not been from the big fifty. The weapon had to be a 7.62 X 39mm. The Chicom round of the communist invented and baselessly vaunted AK-47. The round packed only half the power of the American NATO rounds used in our own M-60. The M-16 rounds produced about the same muzzle energy but were much more effective at close or far range. The AK’s were also notoriously made of stamped metal that would cut unprotected fingers to shreds unless great care was taken with their selection levers, trigger guard and more. The AK round damage would not be visible if Tex had been hit in the back, and the river washed away the blood.

I put the binoculars down in front of me. I was thinking about rescuing him as if Tex was laying there wounded. The man’s body gave no evidence of that. He’d been hit hard, gone into the water and drowned if the wound hadn’t killed him first.

“Is he alive over there?” Jurgens asked, moving to lay next to me.

I looked over at him, only a few feet from where I was. The man’s eyesight was terrific. To my unaided eyes, and I saw twenty-fifteen, Tex’s body was only distinguishable on the other bank because I’d seen it in the binoculars and now knew where it was. My mind roiled with clever responses but I didn’t answer. I simply wanted to kill Jurgens at the first opportunity, and never speak to him or hear from him again. The air came out of my lungs. I’d been holding it ever since the rottenest noncom in the entire corps had lain down next to me. I inhaled deeply, and then could not stop myself from commenting.

“You were supposed to throw the fucking rope,” I accused, my anger seething out.

Jurgens smiled a cold smile.

“He may still be alive over there,” he said, without any emotion in his own tone.

“It should be you,” I hissed.

“And if it was, you’d be laying here with him, regretting it was me who took the round?”

I wanted to shout “no” at the top of my voice but didn’t. I hated the man down in the very core of my being. I hated myself because he was also right. I’d have felt nothing but relief if it was his body was laying over there, and we both knew it.

The drums continued their beating. I tried to place where they might be hidden, but the dull thumping came from everywhere. The drums had come in the middle of the night before but they were just as intimidating in the day.

“They’re pissed off,” Jurgens observed, as Nguyen crawled up and across the berm to slip in beside me. “He’d tell you that, if he was the talking kind,” Jurgens went on, pointing vaguely toward Nguyen.

The Montagnard ignored the sergeant like he wasn’t there. I handed the binoculars to Nguyen. I knew where he was looking and what he was trying to see.

“They get really pissed off when we hit them hard,” Jurgens continued. “They do the drums when they’re mad about losing, which means the Sandys probably finally took care of their fifty, which is good news, indeed.”

“I ordered you to throw the rope,” I said, not wanting to listen to the man become rational, and spouting cultural knowledge I knew I needed but didn’t want to hear from him.

“No, you ordered me to get the rope across,” Jurgens replied with his voice level and calm, in contrast to my own. “I asked him if he’d make the toss because he’s, or he was, tall and looked like he could throw a hundred yards if need be. He thought it was a great idea.”

“He’d never been in combat,” I replied, my own voice going equally as low as his own, but still filled with strong emotion. “You knew or guessed that. You didn’t happen to mention to him that he’d be standing on that bridge exposed to every sniper in range.”

“We send FNG’s to the point, Junior, and you allow it when it happens,” Jurgens replied, his flat delivery making me all the angrier. “He was an FNG, and it was him standing up there or me. I picked him.”

I reached my hand back toward Fusner, and he automatically filled it with the command handset. It was hard to believe I hadn’t called artillery in almost two days. Air power had worked, sporadically, to keep us alive at critical points but there was nothing like on-call artillery for some sense of continuing security. We’d have to move at least ten clicks up the valley to get Ripcord or Cunningham’s fire, though. I got the Gunny on the line almost immediately. He was still referring to himself as the six actual, which wasn’t bothering me much anymore.

“I’m coming across before anybody moves our way,” I said. “When’s resupply due, and did you order 106 rounds for the Ontos?”

“ETA is forty minutes from you know where,” the Gunny came back. “Why are you coming the wrong way?”

“Tex got hit on the bridge throwing the rope over,” I replied, understanding that he was telling me resupply would be heading down the valley, probably from either Hue or Ripcord itself. Army firebases were equipped and supplied with many more war toys and supplies than Marine outposts.

“Who’s Tex?” the Gunny asked.

“Army Engineer lieutenant who brought the Ontos down 548 to bail us out,” I said, stretching the truth in order to gain the Gunny’s favor in what I was going to say next.

I knew Tex was much more the advance party for the building of the ARVN firebase, our original mission than he was sent to save us or even get us across the river. The engineer battalion wouldn’t have had time to put together a rescue and get it all the way down the valley in as short a time as they had.

“His body’s down near the curve up on the bank, not far from where the tank is, but it’s in defilade. You probably can’t see it,” I informed the Gunny. “I’m coming over to recover it with Nguyen and Jurgens. Have Stevens get down there with a corpsman just in case.”

Nguyen pushed the binoculars back at me and pointed up toward the end of the bridge.

I put the handset down and focused the glasses.

“God damn it,” I whispered. The company was crossing, one Marine at a time, with at least five in the water, and some scrambling up onto the bridge’s metal tines levered out over the water.

The drums beat faster. I felt them between my shoulders and between my eyes. I wanted to put my head down and hold it with both hands, or maybe at least put the sound deadening rags back in my ears. But there was to be no avoidance. I watched the careful and slow struggle of the Marines to get across the river. The current dragged at them piteously, pulling their lower bodies downstream while they hung on for dear life, moving hand over hand with their packs and gear somehow secured to them. They looked like huge flopping turtles. There was no enemy fire, only what Jurgens described as the angry drums. I knew immediately that there was not going to be a party of men going the other way, and if a party did cross after the company came over then they’d be on the other side with no infantry support except what could be provided from this side of the river. The Gunny had thought about my plan for only a few seconds before blocking it and substituting one of his own.

I knew the company move would be explained away as a natural result of the forward attack to accomplish the mission if the subject ever came up later. I looked back at Tex’s body. Not one Marine was working his way down the bank toward where he lay, invisible from the company but obvious to the rest of us. I wasn’t angry about the Gunny’s clever countermanding of my order but my insides, where not affected by the awful drumming, were inflamed with white-hot anger at the Gunny’s failure to order Stevens and a corpsman to risk moving across the open area to get to Tex’s body.

I fought to control myself, taking some time to scan the river, up and down its length. Tex had gone in from the end of the bridge. He’d hit the water and, probably without taking a stroke, ended up inside the bend where the river curved slightly, as it flowed around the heavy tank’s body, before recovering itself and rushing downriver.

I came up with a plan. It was personal. If I was to tell anyone about it then Fusner would no doubt declare it the “You’re on Your Own” plan.

I handed the binoculars back to Fusner, along with the radio handset. I knew I should be checking with the Sandys to see when they’d be departing. I looked at my Speedmaster. I had thirty-five minutes before resupply would be coming down the valley, no doubt with at least two, and maybe more, Huey Cobra gunships. Without the enemy fifty coming back into battery, and with the air support hopefully available, the company might likely get safely across the river, occupy the area near the old airstrip, and have a pile of resupply, with food, ammo, water and 106 recoilless rounds waiting. Tex figured out how to fire the guns on the Ontos, and I prayed there was someone else in the company who’d served with the weapon or had similar natural talent.

“Forget about the crossing,” I said to my team. “They’re already crossing this way. I want Abraham Lincoln and Nguyen out on that bridge waiting for me. I’m swimming over and coming back on the rope.”

“I should be here for my platoon, anyway,” Jurgens said, quickly. Fusner, Pilson, Jones and even Nguyen turned their heads to look at him, along with me when he got the words out.

“What?” he whispered. “I’m a platoon commander.”

“Tell the Gunny I’m coming across to relieve him,” I ordered Fusner, ignoring Jurgens. I glanced at him once and caught the look in his eyes. I knew he got the message. We would deal with one another later.

“What does relieve him mean, sir?” Fusner asked, holding the handset to his chest.

“He’ll know,” I said, before stripping down to my utility blouse and trousers. I would not surrender my boots again or my .45. My pack, my canteen, my helmet, and liner, however, would all stay with the team.

“You’re going to swim over, sir?” Jones asked, getting ready to leave his own stuff and move out with me.

“Not exactly,” I replied. “Float over’s more like it.”

I crawled away on my belly, after checking the Colt to make sure the strap was secure. I couldn’t afford to leave the gun and I couldn’t afford to lose it. Another unreasonable and dilemma decision, I thought, wondering if the drums were driving rationality from my brain. I had to go. I would not spend whatever was left of my life wondering if I’d left Tex to die slowly by the side of the Bong Song River.

I got to my hands and knees and pushed through the final low brush barrier between myself and the bank of the river where the bridging tracks were mired deep in the mud. I heard Abraham Lincoln Jones right behind me, but Nguyen was nowhere to be seen or heard. I peered at the bridge, already dotted with Marines struggling to carry their stuff and get across the open flat steel to cover on our side.

There could be no more crawling. I got up and ran, moving as fast as I could and not bothering to zig zag. Any sniper would be close enough with a high powered weapon not to have to lead me, anyway.

I made it to the rear of the bridge and threw myself up to the flat surface. Jones was fast and agile, as he came from behind, diving and sliding right by me. I looked out across the surface of the dull green metal. There were two parallel tracks laid down, each about three feet from the other. The tracks themselves were about five feet wide. The surface tracks were roughened and rusted but looked steady and sturdy. The Marines were crawling toward us on the upriver track but there was no one on the downriver metal surface, except a figure lying down at the end.

It was Nguyen. How in hell the Montagnard had gotten so far ahead of us without my seeing him, was astounding.

He looked back at me, as I crawled across the rough slightly painful surface. In spite of the interrupted treads on top of the flat structure, I felt it was too slippery to try running on. Going into the river in the wrong spot might well cause me to be dragged past the tank on the wrong side, and then into the vortex of the unknown jumbled waters downriver. I crawled as fast as I could, more worried about the swim than sniper fire. The drums drove me on, those and the image of Tex’s boots bobbing up and down in that small eddy.

I got to a point only ten feet or so, from the end of the bridge. It moved gently up and down with the rushing water putting pressure on its suspended and unsupported bottom. The last ten feet of the extended tine was of painted flat metal. Nguyen gripped one raised runner on the inside of the protruding end, which was slightly slanted down to the rushing water below. I knew it was slippery because I had no time to prepare my entry. One second I was sliding down the metal surface and the next I was plopped head first into the water. I surfaced as fast as I could. I was okay, except I’d not had a chance to tell Nguyen why I wanted them at the end of that bridge. I treaded water lightly, my boots a drag on my ability to stay high above the current, but no threat in dragging me down or impeding my ability to make some progress using the breaststroke. It was all going just as I planned until I slammed into the side of the tank. The water heaping up to go around it had masked its presence.

The air was pounded out of me with one crushing blow, and then I was around the iron mass and trying to stay afloat. I tried to relax, knowing my diaphragm would recover, but would it do so before I passed out? Finally, I sucked in the first vital breath of life-giving air, before I grounded on the far shore. The bank was cut by the passing water. The edge ran deep but the speed of the current was so great it heaved me atop the bank in the middle of the curve I’d seen from the other side. I lay on my back with my feet in the water, like Tex’s. I turned my head and looked at the big man’s body, not five feet away. I looked into his open eyes and saw death until he blinked. I blinked and then stared. He couldn’t possibly be alive. He blinked again.

I rolled to his side and saw the small hole in his back. He wasn’t bleeding. How could he have a bullet hole through his torso and not be bleeding, I wondered?

“Tex, you’re alive,” I said, hovering a few inches from the ground next to him.

I didn’t want to touch him, as if my touch alone would cause him to be dead.

He coughed, very gently and I saw blood. He was bleeding from the mouth, but his mouth kept falling into a small pool. The blood washed away with his every small movement.

“Hello,” Tex rasped out.

My mind went into overdrive. Everything changed with Tex still being alive. I hadn’t brought Fusner with a radio. I had no communications and nobody had come down the bank to join me, although the Gunny had to have seen me, and my own team had to have witnessed my arrival at Tex’s side. I sat up and started pumping my right arm up and down. It was combat sign language for double time. It meant run, and the faster the pump the faster the person getting the sign was supposed to run. My arm pumped at the same speed as the drums beat, and I found that somehow satisfying. Like there was some good use for the drums. I looked down at Tex, and smiled, but kept pumping my right fist to beat of the enemy music.

I reached for my .45, and thought about firing a few rounds to get everyone’s attention in case nobody could see me. My Colt was gone. The strap dangled. The snap hadn’t held. The impact with the tank. I’d taken the brunt on my right side. My hip hurt where the .45 had been strapped into its holster. I was unarmed.

In only seconds I saw three crouched-over bodies running down the bank toward where Tex and I were. The Gunny himself was in the lead, with Stevens and a corpsman following. I laid back down.

“Man, you’re going to make it,” I reassured Tex. “Medivac is like minutes away. I lost my .45 getting to you, but it was worth it. You’re going home to the land of round eyes. Purple Heart, some medals and you’re out of here.”

Tex tried to say something, but I shushed him with one hand, patting the side of his head. I knew he had a chest wound. There was no way he should talk, and I didn’t want him to try.

Slowly, Tex pulled in his right hand from where it’d been splayed out on the muddy surface of the bank. He moved his hand to his hip, then lightly patted it.

I reached down to where his hand was. I touched a holster. Tex had a .45 too, I realized. He was an officer. I hadn’t noticed the weapon on him earlier. I pulled the holster up a bit from the mud under him. It was one of those new-fangled canvas things camouflaged with the same pattern as Tex wore on his Army fatigues. It had a flap, unlike my own. I couldn’t have a flap on my holster because it’d take too long to get the weapon out if I needed it, the way I saw it. I pulled up the flap and eased the Colt out.

I stared at the chunk of machined steel. It wasn’t like my combat .45, the one I’d lost. It was blued instead of gray, and it had neat letters and numbers carved into the side of its slide. Tex had somehow brought a custom .45 to the combat theater. I’d heard of that being done by some officers but hadn’t really believed it was possible.

I looked at the gun, and then down into Tex’s eyes. I held the Colt in my right hand, feeling the custom fit of the personalized butt. I pointed at my chest with the index finger of my other hand, and raised my eyebrows.

Tex nodded, ever so slightly. I knew he had to be in great pain. I watched him try to force a smile but he couldn’t quite form it. I looked up to see the Gunny approaching. I knew morphine was out of the question. The last thing Tex could do with a chest wound was relax or fall into unconsciousness. He had to fight for every breath from the one functional lung he had left.

“He’s alive?” the Gunny asked, although he was looking right into Tex’s eyes when he framed the question.

The corpsman rushed around Tex’s body, and pushed me aside.

“Sucking chest wound,” he declared in seconds. “Got to get some plastic on both holes. He can live a long time, but die later if too much blood accumulates in the lung sacs.”

Stevens helped the corpsman, while the Gunny and I crouched nearby.

I checked my Speedmaster. The resupply was due in fifteen minutes. There was no way we were going to get Tex up and across the river, much less five clicks or so upriver to where the old runway was located. Resupply would come and go and Tex would die.

“Where’s your radioman?” I asked the Gunny, putting aside my anger over what had happened with the crossing.

“He’s across. Almost everyone’s across,” the Gunny replied, with a frown, I watched his expression as it began to dawn on him that he might have caused Tex’s death by delaying getting help to him.

There was only one thing to do.

“I’m going back right now,” I said. “Hold right where we are. I’m going to redirect a chopper right into this position. I hope they bring the gunships.”

I got up and ran, jamming Tex’s .45 into my holster, and snapping the leather strap shut with a slight click as I moved.

I was at the rope in seconds. I had no gear so I leaped into the water and grabbed the hemp line. The rope was good for what we were using it for because it was thick. There were no Marines in front of me. I went hand over hand across the top of the water. In the Basic School I’d set a record for the rope climb, floor to ceiling in an aircraft hangar. I went over the water like a spider crossing its web. When I got to the end of the bridge I didn’t’ have to climb out.

Nguyen hoisted me right up and then Jones grabbed me around the torso, and pulled me onto the slippery metal surface. He didn’t let go until we were both down on the rusty treads further along.

“We gotta get to Fusner,” I said. “We gotta get a chopper over to the other side. Tex is still alive.”

All three of us got up and ran. The drums stopped drumming while we were running, but we didn’t reach the other side before finding out why. The two Skyraiders came screaming downriver, barely fifteen feet over the water. Behind them, a bit higher up and on both sides of the valley, were four Huey gunships split into two squadrons, one flying on each side. The Skyraiders flew over, and I ran, elated with their support and toward the other end of the bridge. The two gunships closest to the nearby cliff dropped down and opened up. On us. I dived from the end of the bridge and scrambled across the mud and sand to the edge of the piled jungle debris. I burrowed in. Our choppers thought we were the enemy. Jones was barebacked and Nguyen was a Montagnard, and God only knew what the gunship crews thought I was.

I burrowed and moved, burrowed and moved some more. I heard more choppers, too far down the valley to be landing at the old airstrip. I didn’t know what was going on, but I had to get to Fusner and I had to call off the friendly air before they decided that the Gunny, Stevens, the corpsman and Tex were the enemy too.

<<<<<Beginning | Next Chapter>>>>>>

I’m dyin here James, when does the next installment come out??

Just finishing it this evening. Chuck should have it up in the morning. Thanks for being after it.

Semper fi,

Jim

Awesome. I’ve read a fair amount of personal accounts from wars over the years and i must say that your personal story has me riveted like no other. The way you write has you feeling as if you are there as a passive observer, unseen but seeing everything.

Thanks you Robert, most sincerely. I am writing the next segment right this minute and reading something like

what you wrote on here motivates the hell out of me…Some of these segments are tougher than others.

I though the writing would be faster but instead things slowed a bit as the bite of losing people moves

right through time to reach me here and now…

Thank you,

Semper fi,

Jim

You hang in there sir, you’re doing fine. I’ve spoken with many vets over the years from different wars. I don’t often hear about the bad stuff, and I understand as much as I can having never served myself. But I have heard many interesting stories of their time in the military. I managed to help one of my dear friends deal with his PTSD from Afghanistan, just by being there to listen. At least that’s what he told me. A lot of my family served at various times. Got to meet great uncles that landed at Omaha, I’ve spoken with guys that were in the Submarine service during WWII. I got to meet and speak with the pilot of the Memphis Belle shortly before he passed and was amazed at the stories he told me.My step dad was in the 101st Airborne stomping around the same places you did but a few years later. He alone opened my eyes to what was really going on over there from what you read in history books. I guess what I’m trying to say is Thank You. and Semper Fi

Thanks Robert. Much appreciate the detail of your comment and the compliment. Thanks for the encouragement and

also for writing about it on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

my husband was at the ashau valley he was running a dozer i believe, he didnt talk much, know he got blown up and took half the plow with it and he ran for cover to the nearest bush with his sgt ! i feel so badly for all you guys had to go thru, it makes me sick, to think the government does this to our men ! thank you all

Thanks for your comments on hear Mar. Not many women come aboard to say anything but wives paid a huge unsung price in that war too.

You are correct in everything you’ve said.

Semper fi,

Jim

Hoo ya!

Thanks for the atta boy here Jay…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim I am still here and waiting for each segment, and I check each day for the next. I saw this on another site that I think some of your other readers mite like to watch. If you think it is OK. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dSjNoDvjKg&feature=youtu.be

Pic gone now – but dude was warin a SILVER ornament above the swords = lite col

Russ, all of our photos are from the Internet or guys sending us stuff of their own.

I brought back nothing from the Nam so I had none of my own. The currently serving officer

of the Minnesota National Guard wanted his picture removed so we took it down.

Thanks for your comment and interest….

Semper fi,

Jim

I had guessed it probably was not a RVN photo but I thought it appropriate. Like all the others it invokes memories in general. Puzzling he didn’t want it shown; I would have been proud. Guess maybe he didn’t want to imply something that was not factual. Anyway, the guy should know it was a good picture of an American warrior.

All veterans have peculiarities and the rest of us have to put up with theirs and they our own.

I don’t understand what the problem was but then I am not living his life either. The last thing

I want to do with this site and story or cause harm to any other veterans.

So down it came…

Semper fi,

Jim

But. The replacement picture puts my mind on the ground there instead of at a stateside function that officers are generally expected to attend. So maybe it is better for the story.

Yes, interesting shot. It’s actually a lot harder to find and then select things that enhance the story instead of taking

away from it. Chuck is usually better than I at doing that, possibly because he comes at from a reader’s perspective and

I have pretty fixed memories of the actual scenes…

Semper fi,

Jim

I’ve read it three times too LT, and hole-E-shit. That’s all I got Sir. SF.

That’s quite a bit Mike. Thanks for the particularly meaningful and heartfelt compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, great read!! I look forward each day in finding time to read more. Anxiously awaiting next installment.

Thank you Kerry. I am working on the next segment right now.

Thanks for the support and the compliment and your writing it on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

James, like one commenter has said already, this is my third time reading this posting. Me, because I had to put it down. The man you chose to recover at great risk, I am now holding my breath to see if he survives to get to Battalion or base camp medical, alive. Had a patient in 1966 with multiple holes in his abdomen. AK rounds at close range. Unit ambushed and he was point. Had taken some kind of hit, and laying on a path. Charlie straddled him and emptied his clip. The GI was alive in a P.I. Hospital by the Grace of God. That is one of the reasons I stopped and started. Pondering fate or Devine intervention.

Another butt hole binder, and more days to come. Thanks for sharing your talents. Poppa

You are most welcome Poppa, although you know I can only answer that comment in the next segment.

Thanks for always being there and experiencing the story and feeling it instead of simply reading it and moving on.

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

Guess these days I am more deep into the latrine with you guys because my first grandchild is communing to Mosul for work, I hear daily. From what I hear DOD boss says no quarter and that’s fine with me. This fight nothing like yours except the terror and nightmares I guess. Also heard he made O 3 on the day of his first mission. Pride in, and fear for, all of those amazing people trying to keep the fight on their dirt. Sleep,well Marine you’ve earned it. Poppa

Thanks for the update Poppa and the angst you make it through.

You are a class act.

Semper fi,

Jim

I have read the last segment 3 times now. Each time I’m seeing a little more. This is a great read.

My own experience was nothing like yours, for sure. My Company and Bn will remain nameless. I was in the Army about 15 miles north of Danang in an old Marine Weapons Platoon compound. My first month in 68, 2 officers were dragged, another guy shot over poker and.3 went into the village and hacked mamason and papason to death over their daughter. We have about 80 in the Company at that time anowhere to go. I knew I was in for an experience, however nothing as riveting as your story. I can’t wait for the next chapter.

2 officers fragged

Got the correction. Thanks for the support and writing on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks Dan, for your being so forthright. Hard stuff for the regular public to believe or internalize

and even harder to live with alone…Thanks for not being alone with us here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great segment LT, don’t know if I would have been as easy on Jergens but time will tell my friend. keep up the good work guess I’ll have a beer to calm down.LOL

Thanks Stephen, I much appreciate the analysis and also the compliment.

I am on it for the next segment…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jergens is a lost soul. His mind is in a deep dark hole where his own survival is all that is important to him. Watching others being shot, doing nothing to help, and telling about like it was some kind of neat story shows he has lost all empathy.Some how I think he has been in the valley for a while and the Gunny knows how sick he is. The men who follow him fear him because of his cold ruthless maniplative mind.

He appeals to your morality to save him but prods you to shoot him, probably because he realizes he is in darkness and really has a death wish.

I wonder how long before his own men or the Gunny take action against him. They see what he is doing and not doing.

Thank you very much Nancy. An in depth analysis. Hard to make of men living in extreme fear and peril form moment to moment.

I am much more liberal in my thinking and forgiving over time.

Semper fi,

Jim

That pic of the LTC (Armor) surely does look very familiar !! This is one suspenseful segment !! Are y’all gonna get the KIA out?? Keep on keeping on !!

Thanks Tex, I am resolving a few mysteries in the next segment being written as I write this.

Appreciate the continued support on here and in the reading.

Semper fi,

Jim

“Friendly fire, ain’t.” My team was coming down into an Army fire base. Moving low and slow. WIllie was just on the pric 10 for comms when a fifty tracer round hit right in the middle of us. As you and our Brothers know it was a marker round for a 106. Willie started yelling in the mic “Check fire, check fire check fire. About 30 seconds of silence that seemed like a year and a young voice came up. S.O.I. Identify yourself.”

Willies voice was still hitting high C. Micky Mouse you m*** f** and I’m gonna personally come down there and kick your ass. More silence and then a laughing voice. “I.D. confirmed. Pop yellow.”

We went down into the base looking forward to a hot meal and every one but Willie was laughing and giggling.

Man, you came close. One beehive and there goes your whole team.

Wow. Usually there’s less than a second between the tracer and the actual round.

Semper fi, and God bless you…

Semper fi,

Jim

Yeah, we talked about that. They had doubt or they would have lit us up. They just wanted us to stay put till I.D. was confirmed. It was a tight one fer sure.

You don’t need to answer.

Sir, you have a great gift in your writing. Thank you for your service, and thank you for making these chapters available in this forum. I look forward to each segment to see what kind of hellish situation you manage to get yourself out of.

And glad that you made it home to write about it.

(Thanks for crossing back over to check on Tex!)

Thanks for the compliment and it never occurred to me not to go back for Tex.

I did not really think I was recovering his body, I just knew that I had to know before

I could leave it. Thanks for the compliment and the support on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

A great story as always, by an honorable man. Thank you, Sir.

Much appreciate the compliment and your sincerity and thought to put it up on this site.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, I think I somehow have been lost from the list for the Updates. I did not receive the last 2 but figured that you had to have written something so I went to the source. Got my fix but left hanging. please double check to see if I am still on the update list. thanks, albert

I will have Chuck check right now. Thanks for the tip and if it is happening to you it might be happening to others.

Thanks for that…

Semper fi,

Jim

Friendly fire is an unfortunate consequence of war, 1/3 of the deaths in Nam were the result of friendly fire. 20 thousand men is unacceptable,and a real travesty.I personally saw a squad nearly wiped out this way.It was my worst experience in country by far. Somthing I will never forget.

There friendly fire and then there’s friendly fire. Mostly, the kind discussed is accidental friendly fire.

I believe that’s the smallest part of friendly fire. Thanks for the observation…

Semper fi,

Jim

I pray that accidental friendly fire was responsible for most of the 20 thousand deaths attributed to it, otherwise it was akin to murder. A very hard thought to accept. I don’t understand what you’re implying.

I understand that you do not understand, and you are the better for it.

Semper fi,

Jim

Google w.w.w answers.com. friendly fire incidents Vietnam

I also witnessed a fragging incident, they missed. My point is that porely trained and careless GIs, commissioned or ncos,caused alot of unnecessary casualties. Most of which were preventable. My opinion only.I was with the 101st AB on fire bases in the AShaw, 1971. I wasn’t a clerk in Saigon.

I came to believe it was all about fear Bill. If you added to someone’s survival potential in a survival situation

then you got to stay alive…otherwise things could get really iffy real quick.

Thanks for your comment on this very difficult and controversial subject.

Semper fi,

Jim

If friendly fire is called in for the protection of your own men, it is justified.

One recently saw an article where a medal of honor was awarded to a U.S.troop for calling in friendly fire on his own position. So apparently our government feels that it is justified.

Well, J, yes and no. Depends upon perspective. Like decorations.

Hang some on your wall and read them closely, because your friends will.

Then decide whether to tell them the real story or the story that somebody else told about what

they perceived to be about what you did.

Two different things, usually. My medals on a back closet wall. I didn’t do that stuff.

I did other stuff but not that stuff. And so, calling in fire on your own unit….

what is the definition of that? Calling it in closer than the Rules of Engagement allow.

Calling it in by giving a phony position so they don’t check fire? What exactly?

Calling it in to take out some problematic situation going on among your own men?

What? Who’s perspective? Usually, only the survivor’s perspective or that

of someone who wasn’t there….

Semper fi,

Jim

Having read thus far in your story about your experiences in the Nam as well as your FO activity, one can understand what you are saying.

One remembers remarks you made about trying to explain what happened to the family of one of the marine members that was killed from friendly fire. I believe you stated that they threw you down a flight of stairs. Such reactions create very negative memories, along with guilt trips that should not be a part of your consideration, yet still are.

From what one has read thus far, one has not seen where you maliciously called in friendly fire. When it is a matter of survival for all concerned, man will reach for the only help available for a reprieve and that is acceptable, no matter what the documentation says.

The parents of that boy did not hear of friendly fire. Their son was

killed by a gunshot wound to the head after taking several hits earlier in the day

and staying alive. Before they found him in the night he’d been talking only of his

parents. I was there, nearby in the same bushes. I wanted to share with them his last

words. I don’t know why. I now understand the depth of their pain and how that would

not have helped at all. They are probably gone now. I wonder if they ever thought again

about the guy who showed up to tell them that he was with their son when he died. I’ll never know.

I never did anything like that again.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great episode you threw at us, Sir–and to again let us dangle helplessly until you crank out the next adrenaline pumping one (which no doubt will get us to the NEXT inevitable cliff hanger). Fear, anger, kill or be killed, raw emotion, basic instincts of survival, making a plan on the fly (while having far less than all the necessities to improve odds of success), basic feeling of humanity to your men and duty to your ‘mission’ Marine Corp and country in the seemingly impossible situation you were thrust into, still trying to figure out Charlie as well as many in your own command,, and engaging in huge personal risk of life and limb “doing the right thing” when it comes to (…what you expect…) to retrieve Tex’s lifeless body (can’t just abandon this soldier’s remains..). All the while under fire from just about everyone (friend or foe) who has a weapon of destruction at their disposal in the fog of combat, and not knowing just who to rely on and trust…or when. Hard to understand why some of the men in your unit still viewed you with disdain and distrust. God bless, and keep em coming, LT….

The men didn’t always see me or come in direct contact with me. It was the jungle.

The first time I got a real glimpse of the whole company was when they had to stream across the river!

As with most of life, they were dependent upon what others told them and the telling wasn’t always

very accurate but always favoring someone, and that someone wasn’t usually me.

Semper fi, and thanks my friend,

Jim

Jurgens is like a crossword puzzle with missing pieces ….

self preservation was never overrated.

Too true JW. Interesting take on that complex man.

Angel in Rockford comes to mind!

Semper fi,

Jim

Stuart Margolin.I never would have thought of that comparison between him and Jurgens…Angel was “shifty”, unlike Jurgens who is unpredictable.

The Ballad of Andy Crocker

Good point. Angel I felt had a decent heart under his conniving never ending scams.

Thanks for your thoughts on this.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, my question is how did the Ontos end up with Army engineers? I thought that was USMC only weapon. Keep up the good work. This is a great story.

I don’t know Mike! I have been told several different stories but the Ontos subject never came up in the field.

It was like a lot of things in combat, just there. Or not there when it was supposed to be. I have heard the vehicles were

Marine only inventory but then some have said that the Army had some at different times too. But I don’t know.

Thanks for the curious question I don’t really have an answer for…

Semper fi,

Jim

The Marine Ontos units were deactivated in 1969 or so, and some of the remaining Ontos were given to Company D, 16th Armor, 173rd Airborne Brigade, who continued to use them until they ran out of spare parts. An Infantry Brigade will most likely have an Engineer Company, and that is probably where the Engineers ended up with an Ontos. In addition to being an Operation Iraqi Freedom I combat vet, I am also an avid historian of military weapons.

Another excellent chapter, leaving us at the edge of our seats and hungry for more!!

Somehow, those guys had an Ontos.

I wish now that I’d paid attention to any detail about it, especially markings.

The military over there marked everything up as their own immediately.

Theft between services and units was rampant in the rear

and also considered more a thing of humor than of seriousness…

Thanks for your research and liking the story.

Semper fi,

Jim

That makes sense. In Desert Storm a lot of Army gear ended up in Marine hands.

I don’t know what the USMC would do without nearby Army units to pillage and steal from!

The Army was and remains most kind about such Marine misadventures…

Semper fi,

Jim

I graduated from Ordnance 4808 school(Armament Repair and Maintenance) at Aberdeen Proving Ground after OCS in December of 1967 and assigned to Fort Sill in January of 1968. We repaired everything that was current in the Army inventory at that time that shoots. I didn’t know the Ontos even existed, it was never mentioned in the 4808 school at that point in time.

The M50 Ontos history is available on the web. It was brought out in the 50s and then adapted for Vietnam all the way from 1965 on.

I don’t know why you never experienced in your school but it was very highly thought of and used in Vietnam.

Thanks for the comment and your own experience….

Semper fi,

Jim

I think I know what’s going to happen with the gunships coming, hope I’m wrong. Can’t believe that you didn’t get any support from your Marines. Picture is anyone special?

We did get a lot of Marine support, as long as it wasn’t personnel. We also had trouble when we were under fire.

Senior Marines, and senior people in general, do not want to come under direct enemy fire. Good sense for personal survival

but not always good sense for mission orientation or the preservation of others. There is no question that teenage warrant officer

helicopter pilots and crews will take a helluva lot more chances to come get you under fire than majors and colonels who might know better…

Semper fi,

Jim

The photo included in this is just a stock photo of an Army engineer I assume? Keep it pumping LT, you’ve a company of supporters that need the story, you have us addicted like the medic to the morphine.

The ‘medic to the morphine.’ That was a delivered line in your comment like a 106 mph fastball across the plate.

I just sat here and watched it blow by, the bat on my shoulder useful for maybe scratching part of my back but useless against

your power. Thanks for that great well-worded comeback SSgt!

Semper fi,

Jim

As usual, Jim, a compelling read! Looking forward to the next chapter.

BobG: The photo is of an LTC of Armor/Armored Cavalry. Crossed Sabers with a tank is the clue. An engineer wears a badge in the shape of three turrets of a castle. The other branch giveaway is the shoulder board color: Inside the gold border: Yellow for Armor/cavalry; red for engineers.

Each branch has their own distinctive symbol, and trim color for the uniform. In some cases, the colors are the same (e.g. red for engineer/artillery) but the symbols are different (crossed cannon for arty). Too many details to go farther in this forum.

Yes, I know Mike. The Marine uniform is similar in its complexity. Hard to pass yourself off as the real deal if you have not

lived that complexity. Where the ribbons all go, where the insignia are put within micro millimeters. And so on and on and on.

Thanks for the detail.

Semper fi

Jim

Thanks for pointing that out Mike, Air Force uniforms are a lot less involved all though we do have a number of different shields in our ‘wings’. When I first glanced at the photo I thought that was the castle/swords, didn’t look any closer since I was hoping against reason that could be a picture of Tex, went back and noted it was a tank after you pointed it out. As to the shoulder boards, I had no clue to the colors. Of course Airmen had to take the ribbing of being called ‘Bus Driver’ by the marines and army.

That photo was taken from ‘open source’ U.S. stock on the Internet, like most of our photos.

I did not come home with much from the Nam and photos were not something we really did in the real combat

anyway. Nobody gave a shit about photographing anything because we are dying…

Semper fi,

Jim

It was the one think I have always resented about Kerry’s service. Where did those guys get all the photographers to take those shots

and why did they bother if they were in the shit anyway?

Thank you for another gripping story…Sure hope Tex is ok..I want to find out what happen to everybody after the war …I leave tomorrow for a military reunion in Savannah, Ga. Polar Bear Sir !! 7th ID. 1969/1970

Thanks Roger. Appreciate it if you mention this rather different book to those guys and gals.

Thanks for the compliment and please have a great time with your buddies in Savannah, one of the finest American

cities on the planet…

Semper fi,

Jim

Damn it Jim…I know for a fact that you leaned back in your chair with the biggest shit eating grin on your face as you finished the last stroke on the keyboard….and re read what you had just finished….KNOWING that it was going to drive us all nuts…you have so many freaking “irons” in that boiling cauldron of Fire you are swimming in …..and I aint talking about the Bon Song….damn….how do you sleep at night??? When I get on a thread of a path that I want to desperately follow and get down onto paper, it drives me nuts if I can’t do it quick enough…..and here you are spinning like a top and we are loving it….just doesn’t get any better ..Semper Fi

Thanks Larry, writer that you yourself are proving you are. Another seamlessly and smoothly put together comment that

always makes me smile…now, even before I begin reading. Thanks for entertaining me while still getting your point across,

and the compliments, of course…

Semper fi,

Jim

Old movie and book: “Drums of Jeopardy”. I’m going to hear those drums in my sleep tonight.

Yes, they still come back to me too.

Funny how you don’t see many used on television or in the movies.

They were damned effective at getting us all on edge.

Semper fi,

Jim

This segment has to be one of your best.Thanks again James . Semper fi

Thanks Rover, much appreciate the compliment…and you are most welcome…

Semper fi,

Jim

The Gunny had thought about my plan for only a few seconds before blocking it and substituting one of his how. (own)??

Friendly fire sucks. Wait – did Jurgens call it in during the rescue of Tex?? Hmmm…

Captivating reading James !!

SEMPER Fi

You know I can’t answer some questions SgtBobD.

Thanks for the compliment though, and I will resolve the issues

in the segments ahead…

Semper fi,

Jim

Intense, I might sit right here and wait for the next chapter. You are doing a fantastic job.

Thank Al, for the compliment and for coming on here to write it where everyone can see it.

Smiling here, as I work away on the next segment…

Semper fi,

Jim

Absolutely gut wrenching, heart thumping read. I cringe with every sentence, crouch as if under fire. You guys are made of balls of steel and courage that most will never have tested as you did. God Bless you. Keep writing for all those who did come home and R.I. P. for all your fallen Warriors.

Thanks William, I much appreciate the compliment and also your willingness to write it here.

I will keep at it…

Semper fi,

Jim

I have seen friendly fire but this is crazy! You can pull the wooly bugger out every time things start to get cozy. Never a dull moment around here! Now I’ve got to worry about whether the Gunny and your support team get shot up or just you. Just shoot Jurgens and get on with your life, damn the luck!

Would that it was all so easy Don. The company is much more an integrated although wildly divers and disagreeable mix

of potent emotion and violent applications to the most minor of ‘violations.’ No single act is taken up without consideration of the

complexities of all the things that might fall out from it. Thanks for your thoughts and conjecture, however and for writing about it on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Man, I love this story! I feel exhausted though, as your writing puts one in the story with you. You also appeal to my senses for going back for Tex, Outstanding, Sir!

A few corrections:

I wanted to shout “no” at the top of my voice, but didn’t. I hated the man down in the very core of my being. I hated myself because he was also right. I’d have felt nothing but relief if it was his body (that) was laying over there, and we both knew it.

The Gunny had thought about my plan for only a few seconds before blocking it and substituting one of his how (own).

I rolled to his side and saw the small hole in his back. He wasn’t bleeding. How could he have a bullet hole through is (his) torso and not be bleeding, I wondered.

Slowly, Tex pulled in his right hand from where it’d been splayed out on the muddy surface of the bank. He moved his hand to his hip, then lightly padded (patted?) it.

I reached down to where his hand was. I touched a holster.

I was at the rope in seconds. I had no gear so I leaped into the water and grabbed the hemp line. The rope was good for what we were using (it) for I realized, because it was thick.

The Skyraiders flew over, and I ran, elated with their support(,) (and) toward the other end of the bridge. (delete and)

I am all over the corrections Richard and cannot think you enough for your help. And thanks for loving the story and being willing to write that on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another outstanding segment…Jurgens is a real piece of shit… I would have killed him…probably…given the opportunity. Nguyen seems to be the only one you can fully trust…how ironic…but true to form…outstanding writing again as always. I await the next segment…

Thank you Mark, I am trying to get as many segments as I can out before the July 4th event in Kansas.

To make my goal of the second book coming out in August I must work my butt off to get the segments done.

Semper fi, and thanks for wanting them faster…

Jim

I’ve said it before and I feel compelled to say it again — riveting!

Another chapter, once again, that seems to be even better than all the rest. Can’t wait for your next segment.

Thanks for sharing, and as always, thanks for your service.

I much appreciate that kind of ‘from the depths’ compliment. I could never ask for more.

I will bw writing the next segment tonight thinking about that. Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

Tex was laying their wonded. There. The gunny substiting it with one of his how. Own. Thank you sir

Made the correction. Thanks for that and for your support on here, of course.

Semper fi,

Jim

Sure hope Tex makes it… very cool that they came down there to bail out a bunch of faggot ass Marines. Like you, though, wonder who would send them down 548 w/o grunts???

Madonna wrote many years later in one of her most apropos songs: “live is a mystery.”

Whom would send a new second lieutenant out to a company that has killed its own officers?

Whom would have failed, time and again, to reinforce that company under the worst of circumstances?

Whom would send new replacement officers without telling them what they were walking into?

Happens in combat all the time. Why I am writing this story…

Semper fi,

Jim

I know I will live this one for the next few night very good chapter

Yes, Dave, you and me both…and on into the next one…

Semper fi,

Jim

Awesome, As usual. Thanks, George

Thank you George. Much appreciate the short but very meaningful compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

I remain spellbound. But for the Grace of God, I have no in country time. Many of my shipmates were not as fortunate. I do have four years active and two reserve. (1962-66)

Thanks Bob. I much appreciate the compliment. I am glad that you did not go out into that shit.

You are here writing comments. Much better place…and much more likely to be the case than if you’d gone.

Thanks again,

Semper fi,

Jim

Great as is normal. Keep up the good work !!!!

Thanks Harold, means a lot to have guys like you coming on here to say something about what you think.

Semper fi,

Jim

The Major in the picture is a Cavalry Officer. I am assuming and hoping I am wrong that is is K.I.A. May we know his name. Looking forward to the Sit. Rep on the choppers.

Bud, I will comment at a later time as to your questions.

I try very hard not to comment about anything where there

may be additional activity of the characters…

Semper fi,

Jim

needs to be own

The Gunny had thought about my plan for only a few seconds before blocking it and substituting one of his how.

The Gunny had thought about my plan for only a few seconds before blocking it and substituting one of his how.

Now for how.

Riveting!

Thanks for the comment and the compliment. I am on the fix and thanks for the editing help.

Semper fi,

Jim

Anther dam good read for this grunt one of the best it was cool Tex has change to make it out. Hope he did. Don

Thanks Don, I will resolve all in the next segment!

Thanks for the support in writing in here…

Semper fi,

Jim

Wow! Master of Suspense!

Thanks Joe, big time compliment. Laconic but to the point a it makes me smile. i don’t intend to be what I am but then

I didn’t back then either…

Semper fi,

Jim

Wow James, from the first chapter of this book till now I have been riveted to my chair as I read every chapter. As always,I look forward to the next chapter with the anticipation of a kid waiting for santa. Two weeks ago I had open heart surgery and my roommate was a gunny. We shared with each other briefly about our service there. Mine nothing like yours. Told him about your book and he got hooked up that night. Now a new friend for life. Looking forward to good times together. Thanks again for your service and your story. Both stellar.

Glad as hell that I had something to do with your new friendship and thanks many times over for recuperating with my book.

Maybe keep your heart beating instead of skipping around a bit! Post surgery and all…

Thank you so much for writing what your wrote on here…a big compliment, indeed.

Semper fi,

Jim

Momma said there’d be days like this,

She just didn’t say there would be so fukin many of them,

All in a Gawdamn row!

Thanks for that very accurate observation SCPO. Those were the days and nights indeed.

Never anything like that in my life before or since, really. And I’ve been around the Horn a few times.

Thanks a million.

Semper fi,

Jim

More action and adrenaline spent in one day than most people experience in a lifetime.

Yes, it was that kind of time.

My life would have other such times but never

again so continuous and sustained with

action, fear, and then more fear…

Semper fi,

Jim

Talk about out of the frying pan and into the fire! Jergens seems to be like a bad dog and last forever. Hope Tex makes it and you get to see him again.

The Gunny had thought about my plan for only a few seconds before blocking it and substituting one of his (how). (own)

Slowly, Tex pulled in his right hand from where it’d been splayed out on the muddy surface of the bank. He moved his hand to his hip, then lightly (padded) it. (patted)

I was at the rope in seconds. I had no gear so I leaped into the water and grabbed the hemp line. The rope was good for what we were using ( ) for I realized, because it was thick. Insert (it)

Thanks again, Pete.

You and the rest of the sharp-eyed readers really help us.

Semper fi,

Jim

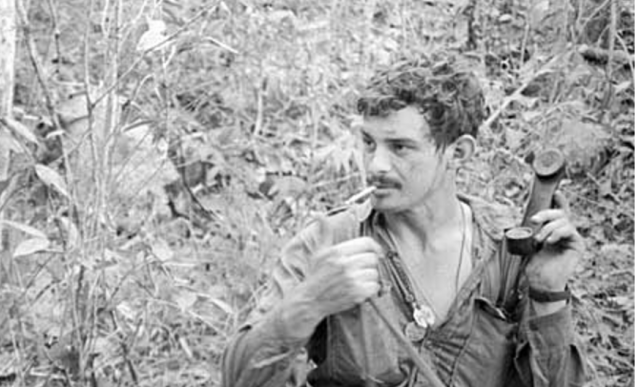

Is the picture of the Major, the Army Cakvary Ifficer, at the beginning of this installment “Tex”?

Yes.

Semper fi,

Jim

The Gunny had thought about my plan…and substituted one of his how. Did you mean own?

Otherwise another good read LT. How Tex makes it, but know the odds.

Semper Fi, Sir!

Yes, I did mean own. Got changed by spell check or correct or whatever.

I hate the automatic editing help, which is little help at all…and delays a lot.

Thanks for pointing that out.

Semper fi,

Jim

doing extraordinary things at extraordinary times I see, well done Lt!

couple friendly edits, para 10 “Tex was laying (there) wounded,

para 42 “occupy the area near the old airstrip, and (have) a pile of resupply

para 80 end of the bridge I (didn’t) have to climb out

I got them rb. Thanks a lot. You guys help make my editing life livable…

Semper fi,

Jim

“as if Tex was laying *there wounded”

“before substituting it with one of his *own”

(no grammar nazism here LT) I hope Tex pulls through.

More great writing!

Check this: The Gunny had thought about my plan for only a few seconds before blocking it and substituting one of his how.

Holy cow James! Just when I don’t believe it can get any more dangerous, it does. Tex is alive, the drums are beating and the choppers are firing at you. I hope I will have fingernails left when you publish the next episode.

Thanks for the compliments inherent in your own comment here. I much appreciate.

I am working on the next segment right now..

Semper fi,

Jim

I don’t know if it can get any crazier LT!!

Oh yes it can Leo. Only reality can get crazier than this. And reality was playing out all

over the place down in that damned valley of the damned. Semper fi,

Jim

The Gunny thought about my plan, the substituted one of his how (own). Keep the good stuff coming, I am hooked !

Thanks Jimmy. Appreciate the public compliment here…

Semper fi,

Jim

James, another great segment.

Thanks for the compliment Tiom.

And writing it on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

Damn, James. My heart’s pounding and you stopped?! Gonna walk outside now to calm down, Hurry up with the next chapter, if you can.

Thanks Kathi, I am writing away this very night…

Thanks for wanting more and the compliment of your writing..

Semper fi,

Jim

Nothing friendly about “friendly fire”

Usually not. So many times not by mistake but out of fear…

Semper fi,

Jim

Unbelievable! You and the world seem to be having a tough time agreeing on anything. “Sucks to be you” seems appropriate. We know it’ll get worse before it gets better, the coming pain is starting to hurt already.

Heading north in the A Shau is not conducive to making new friends

although you do meet new people…

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

Somehow I knew what was coming. We got strafed by one of our Huey gunships. One man was hit in the ankle. The attack was stopped by very angry “WTF OVER” The gunship pilot apologized and corrected to the right target. How they could eff up like that since we were a mechanized unit with Apc’s and a couple of tanks mixed in.

Fear. Fear at the core changes everything.

It allows one Marine to kill another in the next hooch or hole and then apologize.

Fear is a game changer and it’s not something discussed or much admitted to.

In real combat everyone tries to act like a predator but all of us were really prey and we knew it.

The smallest fragment, the lost bullet, the mistake here or there.

Wonderful back here because none of that crap is back here.

Semper fi,

Jim

OH SHIT! It never stops. Man: It Seems you lived 25 years (or more) in your 30 days! How would you say “Murphy” in Vietnamese!

Heart racing, gut clenching segment — again! Gotta read this one again!

Thanks Ed, and for your continued support in getting this story down too…

Semper fi,

Jim

Amazing. I hope Tex makes it. Thank you for reliving all of this for us. I can only imagine how hard it is for you. Thank you and all of the veterans that read this for their service. I await your next chapter!

Thanks for waiting Gary and being there to get it when I am done.

I am about half way through the series now, except for the book that will follow about what it was

to come home in a basket.

Semper fi,

Jim

So glad Tex was still alive. We got fired on by our own choppers. We had just got off our choppers on a LZ and was moving across an open area and into the jungle. I guess there was another CA behind ours and the door gunners opened up on us. Thank God no one was hit before we could pop smoke and be identified. And we were lucky the cobra’s didn’t open up on us. Great episode as usual. Waiting on the next one.

Friendly fire from air was a tough one. It was so hard for the aircraft to actually see where we were and so easy to get

mistaken by terrain that looked so similar. Not like today with GPS and all…

Semper fi,

Jim

It would of been great if we had all the technology and weapons our troops have today. I’m just thankful no one got hit. Our sixty gunner burnt up his ruck sack trying to get a smoke grenade off of it. Keep on keeping on.

Thanks Gordon, I am hard at it, and the technology of today

is a wonder, no doubt, but I also wonder if when in the field things do not degenerate

to the “Lord of the Flies” kind of survival that I dealt with…

Semper fi,

Jim

I have never been a real reader of books or have i ever bought one. But please, please, please finish all three , so that i can buy them all at once. Because I really don’t believe that I can quit in the middle of this terrific. story. Thank you. Bob USN Naval support activity DaNang 67-69

I am working my butt off to get the whole series done. I am about half way through with this very segment.

Next book by August, I pray, and then the third one by December. The fourth book will be about what happens after…

Semper fi, and thank you!

Jim