I awoke in darkness, bringing up my Gus Grissom watch more for the tiny bit of illumination emanating out through the crystal than to see what time it was. I quickly oriented myself to where I was and how I’d come to be there. I heard the wind and river sounds wafting by the entrance to the cave. I breathed deeply in and out, gently sitting up and pulling away from Fusner, who’d apparently slept next to me unmoving through the night, or at least until five a.m., which it was. I remembered that Gunny said he was going downriver to pick up the remaining Kilo bodies just before dark the night before. I hadn’t heard anything since quieting Fusner’s crying and falling unconscious myself. I blinked my eyes rapidly. I felt vital, alive and so filled with an energy I wanted to get up and move about. I needed food and water, and I needed to get out of the cave. I hadn’t heard the CH-46 leaving or return, if it had returned. I’d heard nothing, and that fact was hard to believe since my nineteenth night had been the first I’d truly slept through since I’d been in Vietnam.

I almost whispered behind me to wake Stevens but then remembered he was dead. Zippo was there but I decided to let him sleep as long as possible, and Fusner too. The boy had shown me his age and how much he was holding inside himself. Why I had thought of him as a stoically tough figure I didn’t know, but I had. That he was just another young scared kid bothered me, although I knew it shouldn’t. My job, not his, entailed being the stoically tough figure, and I had to get better at playing that role.

I rolled away from Fusner onto my stomach and crawled prone toward the opening to the outside. I felt the sandy muddy loam of the cave bottom. I felt for leeches like I was searching with my fingers for tiny landmines, but there were none that I could feel or find in the dark. I ran into my helmet and put it on. I knew my pack was somewhere behind me, and inside of it was a box of C-Rations, but I wasn’t going to disturb Zippo and Fusner just for a bite or a drink. I could wait. I stuck my head outside. A bare glimmer of light illuminated the river in front of me and Nguyen’s shiny poncho-covered side. He’d wrapped himself inside a cover against the rain, but he’d stayed right where he’d been when I entered the cave earlier. I wondered if it would be possible to take Nguyen home if I made it back to the world. I smiled ruefully about how great it would be to have the silent Montagnard at my right hand, at my beck and call, around my friends and family, and maybe let him out if some angry motorist wanted to mix it up. But the smile rapidly faded with the reality of the wind, rain and fetid heat penetrating my current reality. If I made it another week and a day then I’d only have a year in the A Shau Valley left to serve. I would have laughed out loud but I couldn’t dredge up any real appreciation for that kind of humor.

I reached behind me and fumbled around until I came into contact with my poncho cover. I’d learned enough to know that poncho covers were dangerous in the night, if it was raining and the slightest bit of light. The rubber surface of the cover would begin to sparkle like Christmas tree tinsel. There could be no threat directly across the river, however, because the cliff face came straight down to enter the rushing water. What was positioned in the highlands above was lost in the wet misery of low cloud cover, invisible at this hour of the early morning.

I moved past Nguyen on hands and knees until I found a flat place to stand, where I could grab the bank for support. The sandy mud wasn’t slippery, except in a few places. I moved slowly. I didn’t want to collapse the bank and fall into the passing water. Nguyen would probably save me but the embarrassment wouldn’t be worth it. I leaned back toward Nguyen.

“Gunny?” I whispered.

Nguyen nodded his head and then used it to motion back over his shoulder up toward where the edge of the tarmac stuck out a bit from the berm.

I was relieved. The motion meant that the Gunny was either back or hadn’t gone at all. Either way, he was nearby, which meant he’d be found in only one place. Where the Ontos was. It would be dry as a bone underneath and the little armored monster wouldn’t sink down on him in the mud because it was set on the concrete not far from the cave.

The tarmac was uncomfortably open and flat, without any flora to provide cover or concealment. I decided not to crawl the hundred and fifty meters or so to the blotch of blackness that had to be the Ontos sitting there near the far wall of the valley. I climbed over the berm and ran, my boots sounding loud, making splashing rebounds at every footfall. I didn’t realize until I got close that I might be mistaken for an attacking enemy sapper.

“Stop,” I heard ahead of me, so I stopped dead, then went down to lay on my stomach in the puddled mess of cracked concrete.

“It’s Junior,” I said, into the darkness ahead.

“Proceed,” the voice said, and I knew it was the Gunny himself. No other enlisted person in the company would likely use that word.

I crawled under the hull at the front of the Ontos. The space was confined, with the armor slanting slightly above my head, Angling down from front to back, it was barely visible in the dark at all.

“What happened?” I asked, unable to wait for his report.

“Recovered the bodies without incident,” the Gunny replied. “Seven of them. They dropped us here about two hours back. You got some sleep.”

He pushed a can against my shoulder.

I grabbed the can, realizing it was a C-Ration container. Heavy. It had to be Ham and Mothers. I pulled my P-38 miniature can opener out from under my utility blouse. The can opener was the only thing on the chain other than one of my dog tags. I never took my dog tag off because it was the only thing I possessed that had my blood type on it. I gently opened the can, working the opener slowly around its upper lip, making sure not to cut myself on the sharp edges of the top.

I didn’t have utensils so I simply turned the cold can up and began letting the heavy grease and beans fall down my throat.

The Gunny pushed a canteen into me.

I drank deeply, and then finished the can of food as best I could, working to not cut my mouth on the sharp metal.

“You have something to say, I presume,” the Gunny said.

I could hear bodies behind the Gunny shifting to pay attention to him.

“Clews is going to call us up on the radio after dawn like he said and we’ve got about three hours to make time.”

“Make time?” the Gunny asked.

“Yes,” I replied, “when he calls the NVA will know we’re leaving to join him, because he’s not going to use code over the radio. He’s too new and he’s only got Johnson and Johnsen with him to advise.”

“Ah, yeah,” the Gunny replied, with a question mark in his tone.

“We’ll be a third of the way there if we leave now, in the dark. We’ve moved several times like that and we’ve never taken heavy casualties. They don’t expect us to move in the dark and they don’t much like it themselves.”

A full minute went by, and neither the Gunny nor anyone else said anything during that time.

“You expect us to be there tomorrow afternoon?” the Gunny asked.

“If we hustle. If the Ontos can make it all the way up the river on this side since we have no ability to cross the Bong Song. We can’t leave it and it’s our only mule for carrying the extra ammo, the new mortars and rest of the crap we appropriated.”

“Why?” The Gunny asked.

“Why what?” I replied, surprise in my voice.

“Why move fast?” the Gunny asked. “The outcome’s a given. We can fire and maneuver our way along at our own speed. Their situation’s done.”

I tried to see under the Ontos but it was too dark. I didn’t know who was there, but every Marine who was there was listening intently to our exchange. I wanted to talk to the Gunny alone but realized that he didn’t want to talk to me alone. He was speaking for the company and I was left in the position of selling to the company.

“We took their stuff,” I said, saying the words gently and not as an attack.

“We let ‘em go knowing they were going to an impossible position.”

I waited by the Gunny, but he didn’t reply.

“We went back for your dead,” I said, not wanting to say it. “We went back for Kilo’s dead. Those living Marines on that hill may make it through the day. We might save them if we hurry, and we’ll risk fewer casualties ourselves if we move now.”

“They’re mostly Army pogues, not Marines,” someone further back in the dark said.

I recognized the voice of Jurgens.

I wanted to kill the man so badly right then.

“We’ll be back under supporting fires, not just air,” I said, ignoring the combined forces nature of Clew’s unit. “I can call one of three firebases as we get close, and make any attack on us living hell for the NVA.”

“Doesn’t seem worth it,” Jurgens responded, still invisible in the dark.

I waited, and the slow dark seconds went by. The rain hit the Ontos and then rolled down the raised armor plate, and then over its rounded front fenders. The sheet flowed across my lower legs, but the space was so low under the thing I couldn’t pull my feet up any further to get them out of the way.

“They know,” I finally said, my voice as quiet as I could make it.

I knew the Gunny could hear me, even with the ever-present rush of the river’s water and the rain coming off the surface of the vehicle.

“What?” the Gunny asked.

I was taking a risk but I didn’t want to talk to Jurgens or any of the rest of them about the move. A decision had to be made and it could not be made by committee.

“They know we don’t do what they order us to do back at battalion,” I said, now speaking so every Marine under the Ontos could hear me. “They know we’re fucked up. I talked to battalion and once we reach Hill 975 all Kilo personnel will be flown out to the rear to regroup. We’ll stay in the field where they leave us because we’re fucked up. If we go get Clews, and those guys are still alive, then they’ll pull us out with Kilo and we’ll get time in the rear.”

“What?” the Gunny, Jurgens and a few others all said at the same time.

I waited. I was lying my ass off. I hadn’t talked to battalion and was hoping Tank wasn’t up on the command net where he might have known that, or any of the rest of them with Prick 25s. I didn’t know what battalion knew or thought and there was no order to pull Kilo out. I knew in my heart of hearts, however, that the company, battered and broken but not beaten, was at a crossroads. If we didn’t go to try to save Clews and the Special Forces guys we’d never make it as a unit no matter what the odds against us. Racial tensions and more would be as nothing if the unit lost its identity as a Marine company and Marine companies did not leave their men.

Not their dead, and never those alive and imperiled.

Jurgens lit a cigarette and I saw his face. His eyes met my own for the brief seconds of the flare and then through the pure yellow burn of his Zippo. My hand was already on my .45, and I wanted to shoot him right there, but the space was crammed with other Marines. I clicked off the safety as quietly as I could, remembering I hadn’t cleaned the weapon in too long. Was the barrel still clogged with mud? Would Tex’s more delicately made Colt even go off? The burn of the Zippo was gone and complete darkness returned. I knew where he was. If he said one more word to convince the Gunny and the others not to go I was going to draw and put five rounds where I knew him to be.

There was some murmuring from the Marines whispering among themselves. I waited. The Gunny had to speak and I wasn’t going to say another word until he did.

The Gunny lit his own cigarette. I saw that his body was only a few feet from my own. He lay on his stomach facing me, his elbows bracing himself up. He looked into my eyes across the light formed by the burning flame of his lighter. The light was gone then, like it had ended so quickly when Jurgens snapped his lighter shut. But my knotted insides, twisted in fear, settled almost instantly. I’d seen a very slight wisp of a smile on the Gunny’s face. He knew I was lying. He knew what I was doing. He knew he’d let Jurgens run off at the mouth because he didn’t want to go after Clews either. But somehow, I felt he was going to side with me.

The time passed. The rain stayed exactly as it was, as did the river noise. A slight wind picked up and gently laid into the sheet of water coming down off the Ontos, and the water’s flow moved all the way up my legs and onto my buttocks. It was almost cold. I didn’t move in the slightest. I could get my Colt out, but I’d have to roll slightly onto my left side to do so. The Gunny was almost directly between Jurgens and me, but if I recovered by rolling to my stomach before I squeezed off the first round, I’d miss him, although the supersonic shock wave of the bullet going by so close would be damaging in a way I couldn’t predict or do anything about.

“What’s this plan supposed to be called this time?” the Gunny said, his voice loud enough for everyone under the armored vehicle to hear.

I breathed out gently for many seconds, making certain I did so silently. I also waited a few more seconds to see if Jurgens was going to seal his own fate. I realized I didn’t want him to speak. I wanted to kill him but I didn’t want to kill him, at the same time, and I couldn’t understand how that could be. Each force within me was just as powerful as the other. I realized it was his call and I was waiting for him to make it. If he spoke, I would fire. But the Gunny had made his decision or he wouldn’t have asked me for the plan.

“The plan,” the Gunny said, his voice becoming a bit forceful. “We’re all waiting.”

“Little White Dove,” I said, knowing the Gunny must somehow have understood that Jurgens’ time on earth was very close to being over.

“Little White Dove?” a Marine said, quizzically, as if trying it out.

Then the other Marines began passing the phrase uncomfortably around among them.

“On the banks of the river stood running bear young Indian brave, on the other side of the river stood his lovely Indian maid,” I said, quoting exactly the lyrics of Running Bear, as I remembered them to be. I didn’t know what the men would think. It was the only thing that came to my mind when the Gunny had put me on the spot for a name. The water flowing down my ass. The river. Indian country. The song.

“Fucking ‘A’,” somebody said. “Little Fucking White Dove. Yes, let’s get some.”

Everyone under the Ontos began laughing quietly, myself included. I would not have to shoot Jurgens, and possibly hurt the Gunny.

“All right,” the Gunny said. “Smoking lamp is out. Get the supplies and heap ‘em up onto our little armored friend here. Saddle up, night move, we’re going up the river to save Lieutenant White Dove.”

I backed out from under the Ontos and into the rain. I hadn’t worn my poncho cover because I was afraid the reflection would shine all the way across and down the river. I hadn’t forgotten the sound of the fifty caliber the NVA had been briefly able to bring on line before our air support had come swooping in.

The Gunny followed me, while the rest of the men crawled out from under the back of the six-barreled beast.

“Battalion, huh?” he whispered, cupping his cigarette against the rain and slight wind. “What’re you going to tell them after 975 and we don’t get pulled out to the rear?”

“What are we going to tell them?” I countered, but the Gunny had gone silent.

“If we stayed here until morning there’d be hell to pay,” I replied, without going further into the lies I’d told. “Air support may or may not come back, but Stars and Stripes are gone, our special combined arms command is gone, and we’re likely to be left as sitting ducks. The NVA’s going to be pissed as hell, and they’ll be chasing us up north once they figure out we got our asses out of here. In three hours, we’ll have light. I can call in the 175s to dump tons of shit back down here and not long after that I’ll have three fire bases within range of their 105s without the steep cliffs to block them out.”

“You don’t have to lay it out,” the Gunny said, handing the cigarette across to me. “You got a gift, and you’re using it.”

I inhaled the smoke and it felt good for the first time since I’d started my strange form of the nearly universal habit.

“Thanks,” I replied, handing what was left of the cigarette back. “I’ll have the supporting fires tap dancing on our dance floor.”

“Nah,” the Gunny said, flicking the remains of the cigarette out onto the mud. “Yeah, you’re good at that. I mean listen…”

I frowned and held my head up. Finally, I pulled my helmet from my head to cut out the noise of the rain striking it. It took a few seconds to hear what the sound the Gunny was referring to. The Marines were quietly singing while they worked to haul the supplies. They were singing the song called ‘Running Bear’ that I had quoted the lyrics from.

“Getting that from them,” the Gunny said, “that’s your gift.”

I moved low and slow back toward the cave. Although the hole in the side of the river bank running back under the concrete of the old airfield tarmac was secure against just about any incoming fire, getting back and forth to the position itself had to be done while fully exposed to sniper fire from the jungle area downriver. Although that distance was almost half a mile, snipers had been known to make much longer shots on both sides. In the rain and dark it wasn’t likely but the crossing still made me nervous when I had to make it.

Nguyen was gone when I slipped over the side of the berm and slid down the bank. The river was rising even further with the onslaught of the steady monsoon rain. If it kept rising at its current rate the cave would be uninhabitable sometime during the next day. Fusner and Zippo were still sleeping. I roused them and got ready for the move. I was energized for the first time I could remember. The pack I strapped to my back felt light. I wished I had better boots but had forgotten to try to swap out with the Stars and Stripes guys, like I’d forgotten to ask them when and where their film would be shown back home, or why they hadn’t wanted any of our names or information.

By the time we reached the Ontos again it was starting to move. The vehicle was perfect in one more way. It was quiet. With the rain, river and wind there’d be no engine noise making its way downriver to the jungle.

Nguyen appeared around the edge of the armored vehicle. That I saw his slippery wet figure at all told me that dawn was not that far off. We needed to move and move fast. According to my map the area between the river and the west wall of the valley would quickly expand out from a mere hundred meters to more than a thousand. That open area wasn’t shown to be covered with jungle. According to the map it was covered with scrub, which meant it had to be left behind each time the river went over its banks and scoured the flat area clear. Using the river’s rising toward the cave entrance as my gauge, that meant that we had to get the Ontos and the company across that open area as fast as we could. Even only a foot of fast moving water sweeping across a mud flat would be impossible to cross unless atop the Ontos, and then there was the problem of its tracks bogging down.

I moved past the Ontos, expecting the rear armored doors to be closed, but they weren’t. The Gunny sat on the flat space of the thing’s floor with his feet dangling out the back. He jumped down at my approach.

“Ride,” he said, motioning toward me to get inside. “You’ll be able to see with the optics better than using your glasses. The crew loaded four flechettes and two HEAT rounds for range.”

Fusner stripped off his radio and pushed it inside before hopping aboard. He gave Zippo a hand. A crewman sat on the folding chair, talking through a hole in the metal wall. I realized he was talking to the driver located in the front of the vehicle. The driver could not see behind us. Nguyen climbed to the top of the Ontos and rode there, fully exposed to the rain and wind, as always. He looked down and our eyes engaged. I realized he’d been there in the dark with me earlier. I’d felt him, although I could not figure out how. It had been a good feeling.

Sugar Daddy came slogging through the darkness and mud, arriving as I was trying to climb through the open back doors. He grabbed me and threw me into Zippo’s waiting arms. Sugar Daddy made no attempt to climb into the now cramped space, however. I pushed against one hard metal wall but my arm ran over curved surfaces. The cabin was filled with extra live 106 rounds. I pulled back. Without being armed they weren’t supposed to be dangerous but their closeness made me uncomfortable.

“I need the eight black guys from Kilo,” Sugar Daddy said, slogging backwards, staying a few feet from the rear of the Ontos moving in the same direction. “I can’t take no FNGs and no more white guys. Just the way it’s gotta be.”

“So?” I asked.

The racial thing would not go away no matter what the circumstance, although there hadn’t been an internal killing inside the unit for several days that I knew about.

“We’re providing your rear-guard escort, the Gunny told us. He said to ask you if it was okay. I’m asking you.”

It was too dark to see the man’s eyes, or even his flat hat. The Gunny was shrugging off the responsibility and accountability again. But he’d supported me with the company when I’d needed him the most.

“Take ‘em,” I said. “I don’t like it and you know that.”

My tone reflected the anger I felt about being put into the position of having to decide something for which there was no decision to be made. I had no choice. And I didn’t like the spoken threat of having Sugar Daddy’s guys as our escort if I said no.

“We’re all Marines,” I said, petulantly, knowing any more comments could only hurt and not help me.

“This ain’t Quantico,” Sugar Daddy replied. “This here is the A Fucking Shau Valley, and I know you know that now. We gotta work it. It ain’t no free ride for nobody. We gotta work it as best we can. Like you do. Like we do. I need those black Marines.”

I would have agreed again but Sugar Daddy dropped away to the side of the slowly moving Ontos and was gone. I knew he and his men would be out there. I couldn’t kill him and Jurgens too. O’Brien was a nearly silent unknown force, like Nguyen, and Charlemagne was a complete unknown. And then there was my mystery corporal or buck sergeant commanding that last platoon I never seemed to run into.

The Ontos rocked and I jammed my back a little further inside until I was against the steel wall. I wouldn’t need the optics of the machine to stare through for at least a couple of hours. I thought about what Sugar Daddy said. I realized that his words were about the wisest words I’d heard put together since landing in country.

I pulled my boots in out of the rain and went to work stripping off my pack. I had a corner of the groaning little machine. It moved smoothly over the mud and debris with little fits and starts, but made good headway, always moving backward. The gunner, or whatever the crewman was, talked constantly to the driver.

“Zippo,” I said, “Break out the Starlight Scope and give the gunner a real set of eyes in guiding us along.”

I didn’t wait to watch him unpack the special instrument. Instead, I curled into a ball and pushed my way in among the 106 rounds I feared and closed my eyes. I thought to myself about Lieutenant Little White Dove and his two ‘Johnson’ officers. Johnson and Johnson was the name of a drug company.

I drifted off to sleep thinking that being named Junior by the Marines around me was a whole lot better than being called Little White Dove.

Running Bear

Johnny Preston

Your great saga continues, James – what a riveting tale it is. I was prime cannon fodder age in 1969, but blessed with a high draft number. Your story along with the Ken Burns series sadly confirms everything I suspected of that era. I recall being at a hockey game in 1973 when they announced “the Vietnam War is over!” The crowd stood and applauded; I sat totally pissed because I knew what a huge lie it was.

btw, here is a link to lots of info about the A Shau in case you’re interested. All my best, Ed.

https://www.cc.gatech.edu/~tpilsch/AirOps/AShau.html

thanks for that Ed and the stuf fon the A Shau too….

Whom would have thought back then that that valley would become synomnymous with

such death and dismemberment…

Semper fi,

Jim

Hey LT, Junior could call up some Marine 4 duece mortars to overcome the cliff obstacles. There were two guns on hill 425. 1/11 W/Y battery.

Yes, the 4.2 mortars were a wonder when you needed high angle fire, and deadly accurate in the hands of those trained gunners.

Thanks for the imput and hilll 425 playes a role….and you must have been there to know…

Semper fi,

Jim

Dear Sir, Thank you for telling your story.

Back in the nineties there was a bunch of us that got together several times a year for a fishing trip up the mountains. One of the guys served in Vietnam, he never talked about it, I never asked. He found out my father was a Marine in Korea and we hit it off. One morning we were in the bar for breakfast, I asked a question about a TV show on Vietnam, I don’t know if it the numerous vodka and OJ he consumed for breakfast everyday or what, but I got the next half hour of his Vietnam experience in all it’s gory detail. It was so chilling I could not believe it. Now your story confirms what he was telling me. He said he was in a unit referred to as the walking dead due to the casualty rate. He was there 68-69. He said he was in the A-Shaw valley and Dewey canyon.

Unfortunately he now resides in the mental ward of a VA hospital.

We need to know the truth. Thanks again for your efforts. God Bless.

Yes, the guys who made it back…didn’t really.

Most of us who came back were ‘repackaged’ by that valley like theGunny said earlier in my tour.

I didn’t come home as me. I look at those pictures of me in college and before.

I smile to myself. That kid had no clue…and that was good.

I have regained so much of my humor and positive outlook

on life itself but that kid, he had that in spades.

The A Shau gobbled him up in a matter of days…

Semper fi,

JIm

We all lose our innocence one way or the other and usually sooner then later. That is a lesson in life which we must learn, in order for us to be able to discern good from evil. Those of us who bare the burden of extreme evil, are and should be the teachers of those who are unaware of what evil truly is.

This is what you are teaching, when it comes to exposing the evils of war. War is never glorious in the sense that it kills and destroys our fellow human beings. The only glory that one might celebrate from war, is ending the evil perpetrated on mankind, by an aggressor nation. We will never see peace on earth, until we see the end of all wars and mankind adopts the idea of live and let live.

The truth, as written by J. Yes, on every point Mr. Wisdom….

Semper fi,

Jim

one of the most gratifing memories was when we brought everyone out of Kae-son,crewed h-53’s some really good times and some of the worst times

I remember when those guys all came out of there, against all odds. The French were not so lucky.

I did not know they all flew out on 53s thought. Great birds thos huge wonderful mothers.

Thanks for the comment and your own history…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim…I’m no combat veteran. I just served and did what was asked of me. BUT..one line speaks all…”You got a gift and you are using it…just listen to them..”

If you don’t know it and haven’t realized it….You are what a leader is and should be…Our nation would be at a great loss without people like you….Thanks…

Thanks Charlie, I guess the role is a bit tougher to see fron the inside out.

Thanks for the compliment in your writing and putting it up on here in public.

Semper fi,

Jim

I look forward to each and every installment. I just wanted to say that the Gus Grissom references are pretty neat, as his birthplace is 9 miles from mine. He died a year before I was born, so I never got to meet the man, but he was definitely a hero to every child that grew up in Lawrence County, Indiana. Keep up the good work.

Yes, I love everything I have come to know about Gus. Needless to say, when I got home

I took to his memory and history as closely as I could when I came home and over the yeers.

Thanks for the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

There were two types of ham and mother’s when I first went in. The original was ham and Lima beans and I loved em! The second was a ham and eggs loaf in a can, the nastiest sponge you ever chewed on. No amount of tobasco sauce could make em eatable! I would eat everything else in the box and throw them away. Before I got out they were transitioning to MRE’s. I wasn’t a big fan! The new ones my son bring home to me aren’t bad but I still prefer the C- rats! Semper Fi!!!

Never got the loaf variety, although heard about it later in the hospital.

MRE’s I’ve tried and they’ll get you by, but that’s about it. The old C-rations

offered real food no matter how processed and the food packed real punch too.

Along with the cigarettes, no less. All the boxes lacked was a small can of Pabst

or Blatz.

Semper fi,

Jim

Evening Jim, LOL, You survived on Ham and Mothers, I survived on Ham and Green Eggs, or as it said on the boxes, Ham and Eggs Chopped Water Added….. The saving grace was the cheese wiz that came with them, I would heat them up with a little JP-4, melt the cheese, and pour it all over the green eggs and ham, I was never at a loss for something to eat, always had about a dozen of them stuffed in the storage …….. The joys of C-rat cuisine, I wish I could find some again and see if they still taste as good as I remember them? To each their own……

Semper Fi/This We Will Defend. Bob.

My second favorite and yes, you can find them on Ebay but the risk is fairly high that

they’ve gone bad. The cans they used back then were not made real well, and most have rusted through.

The only way to know if the stuff has gone bad is to eat it…and I won’t go that far!

Semper fi,

Jim

“This aint Quantico” So much said in so few words.

It was funny that some of the enlisted Marines, who’d likely never been to Quantico, knew it so well

as the sort of heart and soul of Marine leadership.

Thanks for the excerpted comment….

Semper fi,

Jim

Excellent as usual.

“Running Bear dove in the water, Little White Dove did the same. And they swam out toward each other, through the swirling stream they came. As their hands touched, and their lips met, the raging river pulled them down. Now they’ll always be together, in their Happy hunting ground.” Hopefully this is not a portent of things to come….

Oh man, you had to go into the other lyrics. The song was always kind of dumb on lyrics but the music itself was so

addictive….and home…

Semper fi,

Jim

LT. Jim, caught some of a TV documentary on the experiences of some Vietnam soldiers who served “in country” like you did. Even after multiple decades passing since their service to their country, most related how they had battled (or were still battling) war-related demons of their combat experiences in Vietnam.

Someone on the show said [paraphrasing]…”…even though they brought a soldier home and out of the country (Vietnam), they could never seem to take the country [Vietnam experiences] out of the soldier.” I though of you and your men under your command…God Bless, Sir. Still thoroughly enjoying every segment you put up and anxiously await each new one…keep on keeping on…

Thanks fo the great comment Walt and the compliment inherent in the words.

Much appreicate you making thes comments on here where everyone can see them too….

Semper fi,

Jim

Ham and mothers are to you what spinach is to Popeye. Semper Fi LT.

That was very true, and I would eat them today if they still made the mix.

You can’t eat the old C-Rations because the cans have all gone to hell.

I tried ordering off Ebay!

Semper fi,

Jim

Great reading. Brings back plesant on not so plesant memories. Got a little confused in reading middle chapters of second 10 days. You refer to Stevens but then you referred to Stephens? in the middle Are they one in the same? Maybe need an edit?

Al, E Co 2nd Bn 9thMar. ‘Feb66-Mar67

Yes, clerical error by the chief clerk…that would be me! Thanks for picking it up so I can correct it.

Or Chuck, who is better at it.

Thanks for the help, and the neat compliment…

Semper fi,

Jim

We are so fortunate to have such sharp readers……

Found the “Stephens” and believe all are corrected.

Thanks, Al.

Thanks for your sharp reading eye, Al

I think we have the “Stephens” problem corrected.

Thanks again.

Dear Sir,

I am just blown away by this story, your writing and most importantly you and your men. I recently watched Ken Burns Vietnam and there was a quote that Vincent Okamoto gave about his men. “They didn’t have escape routes that the elite, the wealthy and the privileged had. And that was unfair. And so they looked upon military service as..like the weather. You had to go in and you do it. But to see these kids who had the least to gain, there wasn’t anything to look forward to, they weren’t going to be rewarded for their service in Vietnam. And yet their infinite patience, their loyalty to each other, their courage under fire was truly phenomenal. And you would ask yourself, how does America produce young men like this?” God bless you sir and all of the men that did what they had to do.

There was no question that the collection of men and boys was something indeed.

Surprises all the way around. They never failed in the missions but they were failed all the time

by piss poor leadership…

Semper fi, and thanks for the compliment written into your words…

Jim

Still here and reading. Haven’t sent any emails as I figure you are getting ready to soon wrap up the Second 10 Days and are pretty occupied, but we will get back on track soon. I can just see Nguyen standing to the back and side of you at the Thursday morning meeting at Geneva Java, and everyone there nervously looking at him if they are disagreeing with you. One note on Tex’s .45. The custom .45’s are not fragile, they are just more precisely made, with less clearance that the normal government model, and thus could more likely jam from mud and dirt. However, my Colt National Match has never shown that tendency, and has never jammed except when the firing pin stop had to be replaced. I, too, anxiously await the next chapter, and check almost daily.

You are correct Joe, about the Colt. Never had one fail, there or back here.

Never had a failure to fire either, which speaks to the outstanding U.S. ammunition then and now.

Glad you came to visit and really complimented by that effort. Thank you so much.

Semper fi, your friend,

Jim

Your story continues to keep me drawn in. Not looking forward to its ending, but every story has one. Will this be the real end of the story? When finished, provide an epilog giving us what followed with your time in the Corp.

The series will end and the book following will be about getting out of the Corps at that time and then

the books that follow that will be about going to work for President Nixon on the Nixon estate in San Clemente.

I was a long way from being done with my wild life when I got out of the Corps.

Semper fi, and thanks for asking and wanting more.

Jim

Am continually fascinated by the by-play on going between you and the Gunny Lt. At every seemingly critical juncture it appears that you both come to the same conclusions from different angles. Symbiotic relationship is the term which comes to mind. Can’t decide whether it’s deliberate in your writing or something that has just developed over time. Which ever, as I said, fascinating!

It was a complex and fascinating relationship, especially in retrospect. Living it was a bit more hairy and problematic.

Thanks for the compliment and for writing it here in public…

Semmper fi,

Jim

Praying for others is always acceptable to the Big Guy up there! Putting others before yourself, is the primary lesson in life here on earth.

Thanks J. So, today, I am praying for you. Happy Thanksgiving, my friend!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

Praying for others is always acceptable to the Big Guy up there!

Well okay. I shall do so for you this very minute. Don’t be upset if the roof comes down and lightening tries to find you

in the rubble though…

Semper fi, and God bless you,

Jim

James, if that were the case, you would no longer be around as your name has been constantly brought up before the Lord, by those of us who are less worthy then you think of yourself.

Bottom line, none of us are worthy, but He loves us all! If that were not the case, we would all be gone from this planet.

Your blessings are accepted and may they be returned several fold. Semper fi my friend.

Words of wisdom, as usual. I read. I think about the words. Thank you….

Semper fi,

Jim

Thank you Mr Strauss! I meet with the surgeon today! I look forward to every chapter! A thank you for this wonderful edge of your seat story and keep em coming!!!

Praying for you David…hope that’s acceptable to the Big Guy up there.

Thanks for the compliment. Means a lot.

Semper fi,

Jim

Spent my time, 1968-69, on a B52 base in the pacific. You have a talent that brings across what a mess the place in hell was. Thank you.

Correction: “Clews is going to call us up on the radio after dawn,” like he said. “We’ve got about three hours to make time.“ I don’t think you need the internal quote marks.

Thanks for being part of the editing team. Chuck will fix this tomorrow.

And thanks for the compliment…

Semper fi,

Jim

“Gift”, sounds like you finally proved yourself to the grunts. For what it’s worth, I only had one Lt. in S. Korea that earned it and he had to be a Nam vet, we went through several before him.

What you write let’s me compare my time with one of your grunts and it leaves me lacking. Pick any rifleman in any squad, he marched off to kick ass where ever needed while for most of my tour it was stay where you are and tell us (on the obscure chance) when the North jumps. Apples, oranges, luck of the draw, you got the shit, I got the toilet paper.

Thanks Walt, as usual, for the pithy neat comment. Always thinking, and always on top of things.

Thanks a lot for coming in like you do on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

I read some of these comments and I’m humbled. What could I possibly contribute that would add anything to the conversation? This story has become important to me in ways I didn’t anticipate. I think the reason for that is not just the obvious tension created by the A Shau itself, but the wonderful characters you’ve brought to life! From Nuygen to Sugar Daddy they come alive in your writing Jim. As always I look forward to the next chapter. Semper Fi!

You are most welcome Jack and it is a pleasure to know you and read your stuff on here.

The compliments inherent in your words do not miss me by any stretch…and sometimes that is what keeps me

going through the mess of this whole thing…

Semper fi,

Jim

Getting respect is the first sign of a good leader, gaining everyone’s respect is reaching the Great level , which you are heading for . Awesome read, thank you so much for sharing. Best thing I’ve read in do years !!!

What is respect? That’s a tough one in combat.

Things change at an elemental fear-based level.

Respect goes right out the window of harsh circumstance and then maybe comes back in later….

while still waiting to be defined.

Thanks for the terrific compliment…for which I give you my respect!

And appreciation, of course…

Semper fi,

Jim

Okay James…….here’s my first criticism of your entire work so far – where the HECK is the link to “Running Bear”? I LOVE THAT SONG! Okay okay……I’ll look it up myself.

Gary……

It was intended but pushed publish button too early.

Running Bear is now on site.

Thanks for your support.

Semper fi,

Jim

Your leadership is infectious. They are doing what you want thinking it was their idea. Your survival has become their ticket home. All of us just said “get some”. Your endurance had been incredible. Thank you.

Endurance. That was the word. Not spoken or even really thought of at the time.

I am reminded me of Shackleton in the Antarctic or even those sailors with Bligh sailing the world

all the way back to England in a lifeboat. Endurance. Bearing down and just going on, one step at a time,

in pain all the way…

Semper fi,

Jim

Oh darn ,I read it and know have wait for more, thanks for great reading enjoyed every bit of it!

Thanks for the compliment of wanting more and faster…

Spurs me ever onward…

Semper fi,

Jim

Excellent! Your gift given, given in service, as their muse.

I’m not sure if this needs an edit, yet in third paragraph Junior imagined taking Nguyen back home…”I smiled ruefully about how great it would be to have the silent Montagnard at my right hand, my beck and call,…” Should this be beck and call or beckoned call?

Thanks for this and for what’s coming!

Thank your Dennis for the compliment and the notice.

I made slight adjustment.

Semper fi,

Jim

“Beck and call” is correct.

(You can even Google it.)

Looking forward to each section. Thanks.

I was a tank platoon leader in the Army. Volunteered for VN, but they sent me to Texas.

Texas was just a tad better! Or so I hope.. Thanks for the compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Was a young boy, called himself Tom… his parents were killed because they would not support the north… would show up quite often,,, was my buddy,, one night during the monsoons we were pulled out of the bush and put on bridge guard , the VC/NVA had a PA system out in the trees somewhere.. taunting us,, they knew we were wet and haddent been supplied for a few days, so hungery.. telling us to come out and eat with them and other craft… by order Tom was to be put out of the parimiter at night,, but I had kept him with me under the poncho hootch that three of us on that hole watch had put togeather.. any way after s few arty calls in the location of where the speaker was little Tom told me he knew where the Bad guys were.. took him to the CP and he showed them on the map .. fire was called and there was some screeching and then the speaker went dead..no more taunting.. I wanted to adopet him and bring him home.. have often wondered how he is doing…hope he had a good life

There were those rare creatures who seemed to surmount all association except that of honor.

Nguyen was one. Never knew any other of the indigenous peoples there.

Bitter sweet because no, you don’t get to knwo after all these years. Another price, unspoken

and unheralded, of that war. Maybe all wars. I don’t know. Thanks for the depth and meaning of your comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

“Getting that from them,” the Gunny said, “that’s your gift”.”Wow,coming from the Gunny” .Semper fi Lt.

I was as surprised as most of the readers when he said. I didn’t really understand it at the time though.

Why was their singing the lyrics from the song something that was attributable to any talent of mine. I knew I was

great at map reading and calling artillery, but that was it. The rest I saw as just running like hell for my life.

And my leadership talent was mostly making up shit, lying and trying to figure out a plant that would first keep me alive.

thanks for the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

If I had the word passed to me that we were going on Operation Little White Dove. That song would have been the first thing that popped into my head. Grew up with that song as a kid.

I remember an Operation Big Horn. I didn’t like that name at all.

Thanks for the comment on Little White Dove. I still like that song although in listening to the rather weird story and lyrics

I don’t know why. Maybe the nature of the music that lays the foundation for the words.

Thanks for commenting,

Semper fi,

Jim

James, this response has me thinking again,I know dangerous, but your Marines may have been seeing you reflecting themselves, and the way they were driven to survive, first and foremost. But it may have also been too long since they had seen leadership care as much for his dead as he did for the survivors so you maybe had been adopted by the informal tribe of survivors.

Too much speculation but it helps me see the true humanity in men like yourselves. Things still cannot be like they were, but you still keep trying. Character is an attribute to strive for, and I believe you and your tribe had it in spade. Poppa

Thanks Poppa J. We didn’t think so at the time, about the character. We ran on automatic a whole lot.

As least I know I did. And we ran on adrenalin. All the time.

Thanks for pointing out interesting stuff like you always bring up.

Semper fi,

Jim

I wait with anticipation every week for the next chapter in a outstanding novel.. this is better then Clancy..!!!

Thank you so much James. I am into the second to the last segment of the Second Ten Days tomorrow and hope to be done

with the book and have it off to Amazon by the weekend. With the support and assistance of guys like you. The extra little help that I occasinally need to

get along, so to speak…Thanks so much…better than Tom Clancy is pretty high praise….

Semper fi,

Jim

Would Keating’s more delicately made Colt even go off? I think you meant Tex’s. Another great chapter. Thanks

You are totally correct. How did I get that wrong?

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim we both seem about the same age, old farts so you pass that little miss step to C.R.S. [CAN’T REMEMBER SHIT] end quote !!

Thanks Harold. I wish I had remembered to do that!

Semper fi,

Jim

A full night’s sleep. Hooray! What did you do with your second dog tag? Lace it into your boots?

So Johnsen is nominally CO of Kilo but departed with Clews leaving you in command of Mike and Kilo?

Thanks for another gripping installment.

… and clean that .45

Clean the .45, indeed. Funny how stuff like that ate its way into your soul at the time, and then you get home get out of the hospital and there’s like nothing. No weapons to check, clean or even handle, and of course nothing much firing in the distance or close by either. I still listen sometimes when I walk by the stream that runs about a hundred yards from my house. The big pines whisper in the light wind and the water ruffles along beside me. I close my eyes and listen. Nobody on earth, except you here and now, know what I am listening for. Some of you would accurately guess though.

Semper fi,

Jim

At this point in the story, it sounds like the Gunny is primarily responsible for the company’s reputation as fuckups. The night you came into the company, the Gunny had someone putting something in the officer’s boots. It was also the same time that Jurgen’s men were sneaking up to take you out, if one recalls correctly.

While the Gunny generally hangs out with each new CO that comes in, he is never there to save their bacon. He also stands up for the two primary platoon leaders, that never like to obey orders. He grudgingly gives into you, when he has nowhere else to turn, but is always questioning your recommendations. Who is he really trying to please?

Not only does the Gunny disobey the request of Kilo’s CO, to dig in around the perimeter, but he also informs you that he is leaving the area because he knows what is going to happen. Then he helps himself to appropriating supplies that are supposed to go along with Clews and his men, once again putting you on the spot. You are the CO of C company and he knows it will be you that gets the blame.

Leaders set the example for the troops in the company and Gunny is their primary leader who they rely on for final decisions. It looks more likely to me, that Gunny is the primary problem for your company and most of the so called fuckups that take place. Yet he knows that the CO will take the blame for everything, so what has he got to lose?

You see all of this happening, yet you know that the Gunny is the only experienced man to seek advice from and to keep the reprobates from trying to kill you. It is definitely an ironic position to be in. You either hold up the rules and regulations and die, or you look the other way just to survive. You are ate up with guilt, yet you are happy that you are still alive. One could get easily paranoid in that situation.

The Gunny proved to be one of the most enigmatic and mysterious characters of my entire life,

and I have known a few characters.

I worked closely with him, around him, with him and against him….all together and apart at different times.

I liken his conduct to a survival mechanism similar to my own but different.

We did indeed have different talents and he was a whole lot like that guy who takes over

in the Stalag 17 Movie, played by William Holden.

I don’t know who I was like but I’m sure someone (if not you) will find a suitable character in some show from sometime back.

Everything you say in the analysis here is so very interesting.

I”ve never thought about a whole lot of what you write but I’m thinking now.

I would never have believed I could be writing the novels and then being taught about what

might have really happened to the people reading alone as I write.

It’s weirdly and wildly illuminating in a very strange way. Uncomfortable but magnetic, if you get my meaning.

What was the Gunny, really? Who was he?

Semper fi, and my greatest thanks and admiration for you and your brain…

Jim

James, I don’t have the time to proof read your every word. I am riveted to the story you are unraveling and my brain must be compensating for any error you may make. Please keep it coming. I was in Nam in 65/66 with 9th Marines. I credit me surviving my ordeal was I wasn’t there when the real s@#t hit the fan. Thank you for your service.

Yes, Dennis. I do not believe I could have flown in at a worse time and then landed in about the worst place of all…Da Nang.

Funny how real life is about where and when we are somewhere being so causal, when we all think we are so self determined. LIke when someone once

told me that he was not ruled by any chemicals in his body. I asked him if he was hungry after eating two lbs of prime rib. Of course he was no longer hungry.

That quick. And how about interest in sex right after sex? Like gone, man. Chemicals in the body influening thought and actions. Fear does the same thing.

It hits and you dont’ think or act the same, that quick. Reflection is for back here, before the fire, with the cat or dog and the family. It does not

happen in combat. You just move and keep moving or die where you are. Without going back for Kemp he would have stayed frozen in his little hideaway

and that would have been it.

Thanks for the compliment and the writing of it on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

I don’t think the .45 ACP round is supersonic.

You would be absolutely correct. I looked it up. I was wrong in my thinking back then. The .45 ACP at 845 fps travels well below the speed of sound.

Semper fi, and thanks,

Jim

My dad served in the Corps during WW2. The Colt 45 was his favorite weapon. I remember as a kid, him telling me the 230 grain bullet combined with its subsonic speed, was like getting hit in the chest with a 30lb sledge hammer. Saved his bacon on numerous occasions. I carry one to this very day for protection. As usual Sir, your writing is superb and riveting. Can’t wait for the next segment!

Thanks Tim. Yes, tht .45 Colt…and the Thompson firing the same round with the 30 round stacked magazine.

Devastating even in this modern day and age…only if needed, of course.

Thanks for the compliment and the revelation in your comment…

Semper fi,

Jim

That 230 gr round is not supersonic, but under that Ontos it would have been nose bleed loud.

You are correct. About 300 feet per second less than supersonic at sea level.

My mistake, but I thought it was supersonic in those early days.

Semper fi,

Jim

Two suggested edits. You wrote: The Gunny was almost directly between Jurgens and (I), but, if I recovered by rolling to my stomach before I squeezed off the first round, I’d miss him, although the supersonic shock wave of the bullet going by so close would be damaging in a way I couldn’t predict or do anything about. Edit needed: replace “I” with “me”

You wrote: “Nah,” the Gunny said, flicking the remains of the cigarette out onto the mud. “Yeah, you’re good at that. I mean listen (though.)” Suggested edit: replace “though.” with an ellipsis. Sentence would read: “I mean listen…”

You are on top of it.

Thanks Steve W.

Corrected

Semper fi,

Jim

If you end a sentence with an ellipsis, you need 4 dots, not 3, because you are including the period that ends the sentence.

If we go get Clews, and those guys are still alive, then they’ll pull us out with Kilo and we’ll get time in the rear.”

It was a helluva a lie, but it gave the Marines something called “hope” didn’t it.

How you can come up with the plan names like that especially under that kind of pressure amazes me James !!!

Outstanding telling of your story sir.

SEMPER Fi and keep writing !!!

It was a world of deception, down in that valley, of a different sort than back here.

Hence the difficulty of training for it from back here…and of course, because almost nobody

does the training that really walked the walk.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another outstanding segment James…the men are really starting to take to your leadership…they are singing for you again… and what leader doesn’t bullshit his men when he knows it’s needed to accomplish the goal…I think you may be saving Clews’s bacon, if he survives long enough, and surely some of his men…you have the heart and soul of a leader, the marine part included…we are all hung here on this journey, with our memories, as we wait to see what “junior” does next…and what happens in the light of day…

Thanks for the neat compliment so well written Mark. Means a lot to me, as I know you know.

The light of the day is dawning, as the second ten days comes to a head and the next ten days begins.

Thanks for being along for the ride and enjoying the experience, as much of it that can be enjoyed, I mean.

Semper fi,

Jim

James…I read all the comments, like many I assume, but when you mentioned fear making you do things to survive, I thought of my 94 year old WWII vet friend that has several medals for valor. When I talked to him after basic training…he said something that mirrors what you said…he said “we were just a bunch of kids, all scared to death…the only difference between a hero and a coward is which direction you run…I just ran the right way a few times”…that was his response when I called him a hero…much like some of your responses when singled out for your leadership and valor…

Neat that he would echo what I have written on here. He was there. He is real. Not many of those around.

Thanks for the verification and the high compliment at the end…

Semper fi,

Jim

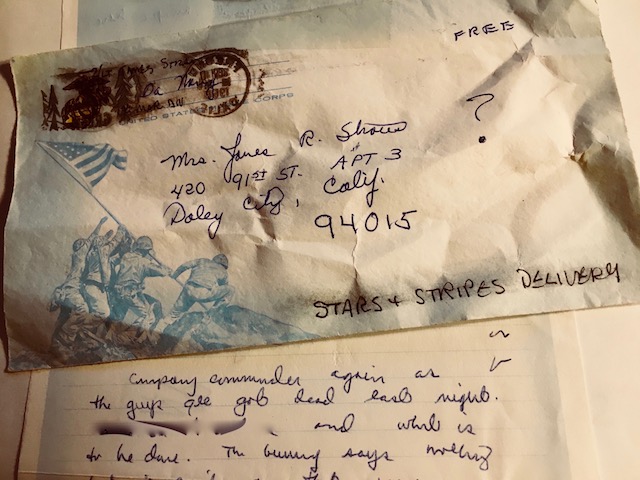

It’s great to see Stars and Strips delivered the mail.

Yes, I knew they would. I just knew it. When I wrote the chapter I forgot that I had written those words with the Major’s pen on the front.

I went through the letters and that comment took me right back to that moment in time. And then I read the graphic part underneath and about choked.

I can’t believe I let some of that crap through to my wife. I asked her about it recently and she said she never really believed it. Good news there.

Thanks for the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another great one. What can I say? As Mike Shields said, I don’t want it to end.

As a side note, your books that I ordered from Barnes and Noble arrived today. It was a very painless transaction. Now I have a lot of reading to do…….

Ken

Neat unreserved compliment in your words Ken and it spurs me on to continue. Thanks for that and thanks a million for bying my books

Hope you love them.

Semper fi,

Jim

When my first ten days appeared here in the Peens, I can’t say I was surprised. You said it would happen.

Because I am in the Peens and it is wet, I put it in a Zip-Loc and purged the air and I don’t open it. I have very few possessions that are dear to me. Dog tags, P-38 and some ribbons That book is one. I read only what I get here on line. Saved and re read.

That brings me to i-books or e-books. Please tell me you will make it happen. I will subscribe and read all when you do.

The beer is cold. Life is good. The is an island just south of me with a bay full of Jap ships to dive on.

I know you are up to your pits in alligators right now but when you take a break you could bring the other two with you.

Stay low, keep movin and change yer fuckin socks.

Sounds like you have found the spot.

Currently The First ten days is available in the

.ePub version (nook and other forms)

and

.mobi (Kindle)

Right here oin site.

Go here and Choose

Ebooks First Ten Days

Second Ten Days before end of month.

Thank you for your support.

Semper fi,

Jim

I am so tickled that you got the book!! I never know, sending it out there in the world.

I can always send another if you want to have a reading copy laying around.

The Second Ten Days is one or two segments from being done so should be out later this month.

The books are all going out as electronic too. First Ten Days is available on Kindle

and on NOOK at Barnes and Noble. Thanks so much for reading, liking and being my special friend in inviting me to come to the ‘Peens.’

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

James: this doggie says you can make all the bloody typos you want, bothers me not one whit!! Write on gyreen!!!!

Thanks for that great succinct compliment James. Really appreciate it.

Semper fi,

Jim

Don’t know if this is the time or place to post this but I feel the need to do so. It comes from a friend who also once served…Another contribution from my friend Pete.

Well written.

He was getting old and paunchy

And his hair was falling fast,

And he sat around the Legion,

Telling stories of the past.

Of a war that he once fought in

And the deeds that he had done,

In his exploits with his buddies;

They were heroes, every one.

And tho’ sometimes to his neighbours

His tales became a joke,

All his buddies listened quietly

For they knew whereof he spoke.

But we’ll hear his tales no longer,

For old Bob has passed away,

And the world’s a little poorer

For a Soldier died today.

He won’t be mourned by many,

Just his children and his wife.

For he lived an ordinary,

Very quiet sort of life.

He held a job and raised a family,

Going quietly on his way;

And the world won’t note his passing,

Tho’ a Soldier died today.

When politicians leave this earth,

Their bodies lie in state.

While thousands note their passing,

And proclaim that they were great.

Papers tell of their life stories

From the time that they were young.

But the passing of a Soldier

Goes unnoticed, and unsung.

Is the greatest contribution

To the welfare of our land,

Someone who breaks his promise

And cons his fellow man?

Or the ordinary fellow

Who in times of war and strife,

Goes off to serve his country

And offers up his life?

The politician’s stipend

And the style in which he lives,

Are often disproportionate,

To the service that he gives.

While the ordinary Soldier,

Who offered up his all,

Is paid off with a medal

And perhaps a pension – though small.

It is not the politicians

With their compromise and ploys,

Who won for us the freedom

That our country now enjoys.

Should you find yourself in danger,

With your enemies at hand,

Would you really want some cop-out,

With his ever waffling stand?

Or would you want a Soldier –

His home, his country, his kin,

Just a common Soldier,

Who would fight until the end?

He was just a common Soldier,

And his ranks are growing thin,

But his presence should remind us

We may need his like again.

For when countries are in conflict,

We find the Soldier’s part,

Is to clean up all the troubles

That the politicians start.

If we cannot do him honour

While he’s here to hear the praise,

Then at least let’s give him homage

At the ending of his days.

Perhaps just a simple headline

In the paper that might say:

“OUR COUNTRY IS IN MOURNING,

A SOLDIER DIED TODAY.”

Patriotism – Pass it on! …. YOU can make a difference!!!

God Bless You James Strauss… Semper Fi

Thanks Jack, means a lot, especially from you…

Semper fi,

Jim

Great piece and I am publishing it on here Jack. Thank you…

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks Jim. To this day I struggle with the fact I was fortunate? enough to not have gone in country as you and so many others did. The loss of some great friends coming home in those bags, plus the loss of some great friends coming home but never coming home and for them not being able to relate as to what it was like being in country. Listening to the bullshit news from political agendas. Watching one of the best friend I’ve ever had die such a slow death from results of Agent Orange last year(Huey Pilot)….crap, he may have been one covering your ass while you were there. Veterans Day this year, at 68 years old is the first time I literally broke down in tears. Actually (even though I’m retired but work general maintenance at an Assisted Living Facility here) I had to get up and leave in the middle of a celebration being held on behalf of veterans. For that I thank you from the farthest depths of my shallow soul. We both served in the same period of time but not in the same world. I’m not a writer. I don’t know the right words to express what it means to hear the truth of what it was for all of you who served, survived and gave all in that pot of hell. Looking forward for the rest of this saga… Semper Fi Jim

Well, for not being a writer you did pretty damned will here on this comment. Deep, penetrating and meaningful. I felt you words and feel your pain.

I am glad you are here and not dead. I like that, even though I don’t know you in person. You sound like a real class act. If you had gone with me asnd

stood shoulder to shoulder with me you would still be here but only alive in the story. I am glad also that you think and feel deeply. That is one of God’s gifts

to special people. You get to know. The wonderful gift and, at the same time, the awful demon.

Thanks for writing this.

Semper fi,

Jim

Sounds like sugar daddy is in your camp now and he just wants to keep his men alive in this he’ll hole.

The waxing and waning of support in combat is without parallel and, although it goes on back here in

the world, it is much more subtle here…where there it is ever present and inescapable.

Thanks for the great comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Sound wisdom from Sugar Daddy! 🇺🇸🦅

Sugar Daddy’s wisdom is sound. But there is more meaning that is not spoken! I needed to clarify my comment! God bless!

Thanks Tommy. I think we all got the depth of your comment…

Semper fi,

Jim

It would seem so, although I had to think about for quite awhile when I was in country.

Thanks for pointing it out here though.

Semper fi,

JIm

Even more visual a telling than ever before. Doing the right thing is rarely easy Another got’er done. LT. Poppa

Thanks, as usual, Poppa J. You are always so spot on with your comments, and here too.

Semper fi,

Jim

Sorry Jim, I’m not editing, but reading and recalling the A Shau.

I really enjoyed the first 10 days and this one as well. Great job

Thanks Dan, I appreciate the read and the writing about it on here so everyone can see…

Semper fi,

Jim

Still here and reading this fantastic story.

A few edits:

I felt vital, alive and so filled with energy I wanted to get up and move about. I needed food and water, and I needed to get out of the cave. I hadn’t heard the CH-46 leaving or (returned), if it had returned. I’d heard nothing, and that fact was hard to believe, since my nineteenth night had been the first I’d truly slept through since I’d been in country. (returning)

I crawled under the hull at the front of the Ontos. The space was confined, with the armor slanting slightly above my (heard,) angling down from front to back, it was barely visible in the dark at all. (head,)

“If we stayed here until morning there’d be hell to pay,” I replied, without going further into the lies I’d told. “Air support may or may (not) come back, but Stars and Stripes are gone, our special combined arms command is gone, and we’re likely to be left as sitting ducks. (add not)

Thanks again Richard,

Corrected thanks to your sharp eye

Semper fi,

Jim

“Air support may or may () come back,. . .” (or may not)

Noted and corrected,

Thanks Mike

Semper fi,

Jim

Another great segment Jim. A great book to me is one that I don’t want to end and I don’t want this one to end. I don’t think anyone has said that you can get the books on IBooks if you have an apple device . That is how I got the first ten days. Looking forward to the second ten days!

Yes Mike,

Thanks for mentioning iBooks.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim,

As many have said, I love your writing. Thank you for your service then and now.

typo:

But the time we reached the Ontos again it was starting to move.

should probably be:

By the time we reached the Ontos again it was starting to move.

Many thanks Ed

Noted and corrected,

Semper fi

Jim

Riveting !

This brings the wetness and misery of monsoon back to me. The racial tensions were building quickly in the I Corps area in 66-67. I can still feel that tension and outrage 50 years later. I worked with the 1st and 3rd Marines. As a SeaBee, I could help provide a few luxuries to these guys and I always felt all was secure when with the grunts. They watched over me but would call me to help if they needed a generator fixed at a check point or an extra hand firing the 105’s. I watched animosity between black and white and the same between some of the lower ranking Marines. I kept out of it. All-in-all, the Marines were an awesome group of warriors. I was proud to serve beside them.

Thanks Charles. You were one of those rare guys, like corpsmen, who the Marines think of as Marines and not from another service.

I know you know that. Thanks Marine for your service with us and for being here at my six too.

Semper fi,

Jim

As always, another chapter in one damn crazy story. Well done…

para.1, line 9 reads: “hadn’t heard the CH-46 leaving or returned, if it had returned.” Consider “hadn’t heard the CH-46 leaving or returning, if it had.”

approx halfway down: “Air support may or may [not?] come back,…”

Thanks Lee and our other sharp eyed readers.

Noted and corrected

Semper fi,

Jim

A full minute (when) by, and neither the Gunny nor anyone else said anything during that time. (went)

Hope that ontos makes the trip as soft mud isn’t a good thing with heavy tracked equipment. I am amazed at the ability to pull up plan names on such short notice that fit so well.

Dang it Pete, you are so sharp.

Corrected and thanks.

Semper fi,

Jim

I am impressed by the small details in your book . I was with India Company 3/5 66-67 and have vivid remember of Ham and Lima (mother’s f$$$ker) .The saving grace is that C-ration meal also contained Fruit Cocktail

Semper Fi

For me I think it was the immediate caloric hit of the grease that held the ham and lima beans in stasis.

I needed the immediate energy. I also liked the taste, for whatever reason. And the fruit cocktail was a delight.

I liked the crackers but there were never enough of them and they made me thirsty…

Semper fi, and thanks for mentioning that detail…

Jim

And chocolate I traded my four pack of Cigs for a better food and guess i was weird I liked the ham and eggs with a little heat

Ham and eggs were my second favorite. We had so many cigarettes in extra boxes from

people back home there was no trading of those in my unit. Thanks for the information and for writing it on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

“If we stayed here until morning there’d be hell to pay,” I replied, without going further into the lies I’d told. “Air support may or may come back, but Stars and Stripes are gone, our special combined arms command is gone, and we’re likely to be left as sitting ducks. The NVA’s going to be pissed as hell, and they’ll be chasing us up north once they figure out we got out asses out of here.

Last sentence: …once they figure out we got “our” assess (not: out)

WOW,

Again your readers are outstanding.

Corrected and Thank You.

Semper fi, Jim