I stood with my right-hand flat, the dirty index finger of that hand slightly glued to my head by a light bond of drying mud. I stared into Clews’ eyes, waiting for an answer. Was I going to live, or die with him? Was I going to do something terrible to everyone inside the cave in order to allow me to live just a bit longer?

“Are all the supplies aboard the 46 or you want us to unload the 47s?” the Gunny asked, the tone of his voice matter-of-fact, like all of us jammed into the cave were sitting at some warehouse desk instead of tensely standing and closely facing one another.

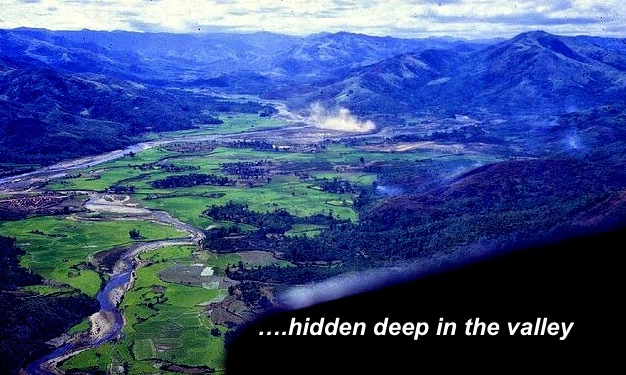

“We’ve got our own stuff,” Clews replied, looking away from me. “We’re going to drop onto the top of Hill 975 just up from Highway 548. This ragtag bunch of whatever the hell you are can make the hike in two days…maybe. Use the 46 to get your dead and wounded back to the rear. We’re done here. When you make it to the hill, get ready for inspection. A lot of the problems I’ve heard about, now that I’ve been here myself, are the result of piss poor leadership and slovenly-looking conduct. This is the fucking United States Marine Corps and you’re damned well going to look and act the part when we meet again.”

I slowly brought my hand down to my side, letting it rest on the butt of my Colt. I was staying. I wouldn’t have to shoot any of them. My relief was so palpable that my shoulders drooped as I slowly breathed in and out.

“Yeah, you ought to feel exactly the way you do, Junior,” Clews said, misinterpreting my body language entirely, with his voice resonating deeply throughout the cave. “This is nothing more or less than your screwup from one end of the valley to the other. If lieutenants weren’t in such short supply back at battalion you’d be attending a court martial back on Okinawa.”

“A court martial on Okinawa,” I repeated, my voice less than a whisper, only the Gunny apparently heard.

He grabbed my upper left arm and gently pushed me toward the opening in the side of the riverbank.

He pushed me through the opening, and then quickly lit a cigarette. Without taking a puff he handed it to me.

“Stay,” he hissed, his dark eyes penetrating my own.

I frowned slightly but accepted the small smoking cylinder. The Gunny turned and stepped back inside. I could hear him talking, but the rushing of the nearby river water blurred out my ability to comprehend what he was saying. I was relieved to be where I was. I put the cigarette to my mouth and inhaled, before bringing it down and examining the mud my fingers had instantly transferred to the white paper. Would I smoke when I was back in the world, I wondered? If I did, would I ever smoke a cigarette and not leave muddy prints all over it? I looked up and across the runway toward where the helicopters sat. Behind me, the Skyraiders continued to pound the jungle area, like they never had before the coming of Clews and the Stars and Stripes guys. Their attacks were like old news to me since I no longer felt any real threat from the area they were working over. The Huey Cobras had all joined together to form a buzzing flock, like high-flying blackbirds, buzzing higher above the valley and no longer firing down onto the jungle below.

The Fort Bragg Special Forces guys, looking like real combat veterans, had gathered the media people and gotten them down, forming a round perimeter around them that was more like a circus ring inside the bigger ‘tent’ of my Marines’ larger perimeter surrounding the whole end of the airfield.

I looked over toward where the choppers sat, and watched Marines working quickly to unload supplies. The Gunny came through the opening and joined me. I handed him the rest of the unfinished cigarette, which he accepted gratefully, before handing it back. He glanced across the tarmac and exhaled mightily.

“Shit, just one more thing,” he said, ducking back inside the cave.

More unintelligible conversation went on inside. I waited, finally flicking his cigarette out into the raging brown waters of the passing Bong Song. I had no idea of what was going on inside the cave and I had a feeling I didn’t want to know. I wasn’t going with Clews and I was coming to understand that that was why the Gunny pushed me out and why he was still talking to the officers inside. He was saving me from myself again, unlike my inability to do the same for Clews and his officers.

All of a sudden everyone from inside began to file out. I backed up and then moved to the side, where Fusner and Zippo squatted in the mud, having dug shallow trenches in case of any incoming fire from across the river, as unlikely an event as that might be. Nguyen was further down the bank, standing in a weak eddy of the passing water, a sharpened stick in his right hand, his attention fully upon the water flowing lightly around his calves. He was fishing but I didn’t see how he could catch anything since the water was too murky to see through.

“I’ll get my guys and we’ll do a quick photo op,” Major Whittier said, he being the last to exit the cave.

“Yes, sir,” I replied, knowing I had no real choice at all, and not giving a damn about that either.

Moments later the major returned with his officers and some enlisted men. They set up some tripods while the Gunny smoked another cigarette, his full attention on the waiting choppers for some reason I couldn’t fathom.

“They’ll be on the Prick 25 when they get dropped atop 975,” the Gunny said, between puffs, “and we’ll get our orders to start our own hike.”

Clews, and both Johnson and Johnsen led their unlikely collection of Marines and Army Special Forces back toward the rear CH-47, its tandem rotors already slowly turning, as if the machine had sensed the approach of the combined arms outfit.

“Fusner,” the Gunny said. “Turn off your Prick 25. Tank’s already shut his down.”

I looked from the Gunny to Fusner and then back at the Gunny. He’d never ordered Fusner to do anything since I’d been with the unit. I waited for the Gunny to explain himself while Fusner obeyed the order, but all the Gunny would do was stare out over the lip of the river bank to intently watch the departing chopper. I moved to stand closer to him.

“What was going on in there?” I asked, not wanting to countermand or question his order to Fusner, but wanting to figure out what was going on that seemed to be causing such unusual conduct.

I looked out toward the CH-47, its blades whirling at a speed that made it seem it would lift off at any moment, but it didn’t move. A single figure came down and out from the still lowered rear ramp of the machine. It began moving toward us, but its steps grew half-hearted before stopping entirely. Finally, the figure turned and walked slowly back to the helicopter. Half a minute later the giant Praying Mantis of a machine closed its ramp and leaped into the air, its rear rotor rising rapidly at first, before the one in front. Once off the tarmac, the machine accelerated rapidly, rushing toward us as it gained altitude and moving right over the top of the approaching media team. The Stars and Stripes personnel went face down on the concrete to wait out the wind storm. The Gunny waited until the climbing bird made its turn to fly back up the valley before commenting.

All of the Huey Cobra gunships dived down and flew around the departing chopper like it was a queen bee and they were the guarding drones.

“I was stalling,” the Gunny said to me. “I was telling them all the reasons we needed you right here instead of at the top of Hill 975. I was lying my ass off.”

I was shocked, at first, that the discussion had been all about me, before the first part of what he said clicked in.

“Stalling?”

“You can turn your radio back on, Fusner,” the Gunny instructed.

“What the hell?” I said, knowing the radio and the stalling, and probably even the departing figure’s strange behavior at the CH-47 were all linked, but not able to figure out how.

“We unloaded most of their supplies,” the Gunny said, still staring at the disappearing chopper. They had 106 rounds, 81-millimeter mortars and about twenty Jerry cans of gasoline. They won’t be needing any of that shit, but we will, once they change our mission again.”

“We’re not going to Hill 975?” I asked, wondering how the Gunny could possibly know such a thing.

“Oh, we’re going alright. We’re going to go there to bag that whole lot up, and then get the hell out of there if we can.”

“We stole their supplies?” I asked, still trying to take it all in, “we stole our own commander’s supplies?”

“Appropriated,” the Gunny replied.

“I don’t like stealing from our own Marines,” I said, flatly.

“Call it whatever you want. We’ve got gas for the Ontos and a full load of rounds. The NVA fear that thing and we’re leaving Indian Country to head up into Delaware.”

“Delaware?” I asked.

I waited for the Gunny to reply, not that it mattered, I knew. I’d figured out what was going to happen when Clews had been talking to me in the cave. That the Gunny would figure it out and then take action I should have guessed, although the action he’d taken I’d never have thought of.

“Operation Delaware, right where we’re going. Just down from Hill 975. The Army got its ass handed to it five months back. A thousand casualties in two days. Choppers, trucks and more, all lost. We’re going to Delaware.”

Major Whittier appeared above the cave entrance, followed by his entourage of officers and technicians. All wore the latest jungle utilities, possessed by none of the combatants of my company or Kilo. Their utilities were starched and ironed. The technicians hauled camera tripods and equipment, as well as being armed with CAR-15 Commando assault rifles.

I’d heard of the short little versions of the M-16, but with better suppressors, shorter stocks, barrels and with larger magazines. They looked really cool.

I climbed up the bank with the Gunny and my scout team. Jurgens, Sugar Daddy and even Charlemagne gathered, with some of their Marines. I looked around, as Whittier walked toward me. It was getting to be late in the day and, although there had been a lot of fire across the river and down valley there was no gun fire audible anywhere, although I still felt uncomfortable standing vertically in such an open area.

“That’s quite a helmet, lieutenant,” Major Whittier said, holding out his right hand. “Mind if I take a look?”

I pulled my helmet off and handed it over.

The major examined it closely.

“Wow. This is something. Did you make it yourself?”

The Gunny started to laugh, and then went into a laughing fit, joined by Jurgens and Sugar Daddy.

“Yeah, I guess he did just that,” the Gunny finally blurted out.

“Can I use it?” the major asked, obviously not getting the humor. “We’d like to try out your real combat stuff if it’s okay. Our new equipment doesn’t look just right in the final reels.”

Without saying anything further, Major Whittier and his men began exchanging weapons and attire with the Marines present. I wasn’t asked to give up anything other than the helmet in the eerie minutes that followed. Those of my Marines who got CAR-15s examined them closely and were impressed.

“We’re going to shoot a few rounds if it’s okay with you,” Whittier said, holding a belt fed M-60 with the hundred-round belt draped over his shoulder and falling all the way to the ground behind him.

I thought of informing him that no combat Marine would ever let his ammunition drag along the ground but said nothing. The major was truly impressed with the C-Ration B-3 can jammed into the slot next to the ammunition box so the belt feed could pass over a curved surface and therefore not jam easily.

The Marines present from my company and a few from Kilo squatted down and looked on in quiet awe, as the Stars and Stripes personnel set up their ‘stage’ next to the river. With borrowed dirty utility blouses, field worn machine guns and what real helmets they could find, including my own, they opened up, firing across the river until they were out of ammo. The officers did the modeling and firing while the technicians filmed repeat takes from their tripods. I wondered, in a sort of dazed shock, what any NVA from downriver, who might just be able to view the scene, might think. I also wondered, with considerable skepticism, whether citizens back home, viewing the films, would in any way believe that a bunch of clean Americans, laughing, carrying on and firing from open unguarded standing positions might be even close to being real. After something less than an hour, while we all crouched like Arabian statues and watched, the whole film collection broke up, exchanged out the equipment with thanks, disassembled the film stuff and headed quickly back toward their waiting chopper. Major Whittier shook my hand with a big glowing smile, and then walked quickly away.

I called to him to wait, and ran across the intervening distance, my helmet in one hand and my letter home in the other. I asked him to mail the letter in Da Nang when he got there. For some reason, I knew that particular letter would make it home, although it had been days since I’d written it and couldn’t remember what I’d written on the paper.

The big CH-47 lifted heavily into the air. I crouched over until it was well away, the Huey Cobras diving down and swarming around the media chopper. I realized that they had had time to first escort Clews upriver and come back for the Stars and Stripes people. I wondered if they’d come again for the 46 when it was time for the real Marine chopper to leave. I made my way back to the Gunny, waiting in the distance, not far from the opening to the cave.

“We’re going down river in the 46 to get the bodies,” the Gunny said as I approached.

“When do we leave?” I asked, looking up at the darkening sky, feeling the building of moisture that meant more rain was on the way.

“You’re not going,” the Gunny said. “You and your team need some rest and you’ve done enough.”

I was surprised by the admission that something I’d done might have had merit. I was more used to the kind of presentation Clews had made.

“Kemp,” I said, suddenly remembering the brain-damaged officer. “Where is he and what’s going to happen?”

“He’s down near where the chopper’s sitting on the tarmac with the rest of the wounded,” the Gunny replied. “We’ll lift off, drop down twice, once on each side of the river, pick up the bodies, and come back to get the wounded. I’m taking Jurgens, Sugar Daddy and a half dozen Marines. With your permission, of course,” he added, which surprised me.

I was going to argue that it was my place, that the risk was high, that although the Skyraiders were still on station orbiting around, which meant the NVA would probably keep their heads and bodies deep down in spider holes or even deep underground complexes, that they might take RPG fire, but it wasn’t in me.

“Go,” was all I said, before turning and walking slowly to the edge of the berm just above the opening to the cave.

I wasn’t at all sure that Kemp was even alive, how many wounded we had in total or even how many dead would be hauled out. My knowledge of almost everything about my own men, and now those of Kilo, was ridiculously shallow, and anecdotal, almost to the point of idiocy.

“It’ll get better,” the Gunny said.

I stopped in my tracks and turned to face him. I wanted to yell something back at him in anger but then saw that he was smiling a big smile. He was kidding. There was no ‘getting better’ in the A Shau Valley. I laughed for only the second time in my short tour and, once again, headed for the cave.

I stood by the cave opening and listened as the chopper’s turbines spooled up, and then the much deeper dig of the blades as the pilot guided the big machine into the air, took it out low over the water and headed down the valley.

The Cobras hadn’t come back for the 46. I hadn’t thought they would. We were Marines again. On our own in the valley of no return.

The day was dying as I stood there, with the rain coming back, washing dirt and bracken to flow down the cracked and broken tarmac and make its way over to the ever-raging waters of the wild Bong Song River.

I stood just outside the cave entrance, my battered ‘self-made’ helmet beating like a Caribbean steel drum, the drops providing no rest, no music and no message. The grim presence of the A Shau Valley pounded down upon my head with hundreds of little liquid hammers. I stood in the rain to see across the flatness of the old unused runway, to see the Ontos sitting ready on the far side, its six gaping gun barrels directed back down the river from where we’d come.

Everyone who’d flown in was gone. They’d all flown out into the night and on to their fate. Only the company and the remnants of Kilo remained, dug in, chained together by machine gun fire teams in a perimeter of flaming steel that could be launched with no notice at all. I was visually checking the perimeter, although it needed no checking. I was among Marines, and they’d been consigned to their valley fate long before me, although they’d likely suffer the same fate as me, they’d not go quietly, but rather surprised, deliberately kicking and screaming into the night. I watched the light wind play across the fronds of distant bamboo, waving across the tarmac at me like a bunch of thin overly tall stick men.

I knew I’d fall instantly asleep once I was able to get back into the cave, like Zippo and Fusner inside. Nguyen squatted not five feet from where I stood. We exchanged our usual secret and knowing look. It was all either of us needed of one another, to let each of us know that anything either one of us needed from the other would be provided. How the Montagnard could squat motionless in the rain, without head cover, his back against the riverbank mud wall, and do that during all hours of the night was beyond me. I was no longer inexperienced enough to invite him under cover, however. We were in his valley of the A Shau, Indian country, headed for Delaware.

I heard a faint brush of movement emanating from inside the cave opening. I bent down slightly, the water from my helmet cover running down the back of my neck. It was Fusner, on hands and knees, his face barely visible inside the cave’s near darkness. I saw liquid running down his cheeks and I was momentarily taken aback. The boy had seemed bullet-proof ever since I’d been with the company. His transistor radio was playing softly again, after having been eventually silenced by command of Lieutenant Clews. The light was fading all around me. I wondered if the song was the last of the day for Brother John. I bent and went to my knees.

“What is it?” I said, keeping my voice down so as not to awaken sleeping Zippo.

“It’s me,” Fusner got out, his tone one of misery.

I wanted to wipe his cheeks, but withheld my hand.

Fusner looked about ten years old, and my hardened heart suddenly broke with a shiver of pain.

“What’s you?” I asked, shaking my head gently and then looking around briefly so make sure there was no threat I was unaware of.

“What’s you?” I asked again, when he didn’t answer right away.

“The song,” he replied, sniffling, before wiping his face with a mud-stained hand.

The song. I listened to the lyrics and the gentle wonderfully calming melody: “Just a lonely bell was ringing in the little valley town, twas farewell that it was singing to our good old Jimmy Brown. And the little congregation prayed for guidance from above, lead us not into temptation, may his soul find the salvation of thy great eternal love.”

“What about it?” I asked, after the song ended and was replaced with Brother John’s calming bass timbre beginning to deliver his ritual good night.

“It’s about me,” Fusner whispered, wiping his tears away again. “I know it. My parents live in this little valley. I’m Little Jimmy Brown.”

I didn’t know what to say. Premonitions of death were so regular for me that I couldn’t distinguish from dreamed thoughts of my own demise to conscious speculation of the same.

“Is your name Jimmy?” I asked him. Before he could reply, I went on. “They’re only about forty million little valleys across the expanses of the United States. It’s not about you or your valley. Get back in there and get some sleep.”

Fleetingly, as he turned, I thought about the fact that my own name was Jimmy.

“Will you come?” Fusner said, his voice almost inaudible over the sound of the rain, the river and the fact that he was crawling away from me.

Of course I would come, I thought bitterly to myself. I was coming anyway.

I glanced over at Nguyen as I entered the opening. He didn’t turn his head, water running down his face without resistance. I knew he felt my gaze but he didn’t turn his head. I knew also that the opening to the cave would have a guard more powerful and silently voracious than any tiger or lion.

I crawled in through the opening, stripping off my wet poncho cover and helmet as I went. I laid down next to Fusner, uncomfortable to be needed by my radio operator whom I thought of as being so tough. He scooted over on his back until our shoulders were touching. I thought to pull away, but couldn’t do it.

My mind would not leave the earlier lyrics of Brother John’s last song: “One rainy morning dark and gray a soul winged its way to heaven; Jimmy Brown had passed away.”

My body shook for a few seconds. I felt Fusner’s shoulder against my shoulder. I closed my eyes, feeling better having it there.

Operation Deleware was Apr 1968. Gunny said it was 5 months ago; if this is Sep 1969, it was 1 yr 5 mo ago……

Incredible how a song can not only capture the essence of the moment, but can bring memories roaring back with astonishing clarity.

Yes, gifted songwriters are special indeed.

How they could get it just right and never be around what their lyrics might be applied so perfectly to…

amazing…

Semper fi,

Jim

You wrote: “Half a minute later the giant Praying Mantis of a machine closed its ramp and leaped into the air, (it’s) rear rotor rising rapidly at first, before the one in front.” Edit needed: change “it’s” to “its”

Thanks Steve, for the editing help.

Semper fi,

Jim

Sir, due to nothing more than a lucky lottery number I have not earned the right to comment on your tale. But I want to thank you for maybe helping me understand friends who came home but never quite got here. Thank you for your service & thank you for sharing. Jack Malone

You do not have to earn a right to comment on here.

This place is for all those who have come to understand over time what being

in real combat is like and the meaning of serving and believing in those that did serve.

That you did not go is good news, as you will discover in the reading.

Most did not come back from the A Shau in any physical form…

Semper fi, and you are most welcome here….

Jim

Arrogance, by Marine officers killed a lot of Marines. They were trained as All American warriors, hard, square jawed, and trained as invincible. The could not wait to engage this ragtag enemy an charge the hill. By the time they figured out the NVA an Charlie were really good they and most of their men were dead.I can still the map of Death Valley, it is burnt into my memory.

Yes, burned into my own memory forever, with some of the grid coordinates still right there if I need them along the Bong Song.

Thanks for your accurate and revealing comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Tears come from the tired and weary that have spent so much time in the bush with the death of follow brothers all around and being thank full to be alive. I know… The memories…

Thanks Jim, I think…

You are most welcome Mike. This accidental rendition of my war in Vietnam just keeps on pouring out, every couple of

days I put a segment together after reliving it all in my mind. An interesting odyssey not seen that way when I lived it.

I thought it would be over and done if I ever got home. Wow.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another moving chapter, Jim. I look forward to every one and read and reread each line as it reminds me of my tour. Though not the same as yours, it changed me as it changed us all. Happy Birthday, Marine Corp from an Army Vet. Have a Great Veterans Day to all.

Thanks for the birthday wishes. I guess I grow and bit acrid and bitter about the treatment of returning military

veterans in our culture on my Facebook page but here, not so much. Maybe because here I am have the warm comfort of being

surrounded by brothers and sisters….thanks for being one of those…

Semper fi,

Jim

you wrote: “What the hell?” I said, knowing the radio and the stalling, and probably even the departing (figures) strange behavior at the CH-47 were all linked, but not able to figure out how. Edit needed: “figures” should be “figure’s”

Got it Steve, and thanks for the help here as you guys are all the editorial assistance (other than over-worked Chuck) that

I have…

Semper fi,

Jim

I really have to smile thinking back when I started to read your first book. I purchased it upon recommendation of a fellow vet. As I open the book and noticed there was a disclaimer that it was fiction I was immediately disappointed. Frankly, I much prefer actual biographies and military history. The very beginning Account of your interaction with the general cause me to think that “this book is going to be ridiculous work of fiction. “. Boy, was I ever wrong. It didn’t take me but a couple of chapters to be completely hooked. I greatly appreciate these installments and your comments and interactions with readers. It Gives great insight into the story. I love this work of “fiction.” By the way, are the operation names in the story the ones you actually used? Did you remember the all?

Yes, the plan and operation names are real.

We are headed into Delaware right now in the story.

You can look the Army operation up that preceded our visit and what happened to them

and why that part of the valley became known as Delaware. All the places are real.

You understand the fiction part so I don’t have to go into that.

Semper fi,

Jim

I think we all know why the ‘published’ book is listed as fiction

In 69 my dad was a CO of a FB, He was called in to direct fire because the FO had been killed. When approaching the LZ he saw a chopper and two APC’s burning on the ground. He said the tracers were so thick you could walk on them. Sounds a bit like that army unit that got chewed up.

I dont talk about Nam with vets, cause I wasn’t there. But your letter home stirs up memories. They would move families out so quick. Sometimes five moving vans would show up on a Saturday, fanned out in the neighborhood. The empty seats in the class room as my friends and classmates left without a word. We dependents knew.Still hurts.

Yes, like the missing man formation the Air Force is famous for. We died like flies during that way

and it was all kind of quiet back here in the states.

When my wife answered the door in Daley City while I was away, two Marine’s were there knocking.

She was living with the wife of another Marine officer over there at the same time.

She said, simply: “which one?” They didn’t understand.

I’d told her that they only sent a telegram if I was wounded.

If I was dead there would be two Marines at her door.

When they said it was me she went straight down.

The real stuff from the real days…

Semper fi,

Jim

Happy Birthday Lieutenant and Happy 242 to our beloved Corps. Keep up the good work.

Semper Fidelis

Thanks Gunny. Love writing that word to this day. Gunny. Thanks Gunny.

I owe you and all other Gunny’s out there…and he knows who I am writing about if he ever reads this and is still alive…

Semper fi,

Jim

I wrote this after I started reading your story. They started bring back memories of my time with the 3rd marines during operation Dewey Canyon 98-99.

As a young man, I went to a place called Viet Nam with hopes and dreams.

I was sent into a valley. With those hopes and dreams alive.

I returned from the valley an old man without my youth and soul.

From some of the things I had seen and done.

In that valley called the A Shau.

Poetry, reaching into everyone’s chest who reads it and tearing at their heart.

Like my own. I understand. Others from that Valley fully appreciate and understand.

I am so sorry you had to go and I’m so happy you made it back. Semper fi,

and Happy Birthday, Marine!

Jim

Have the years wrong should be 68-69

I am not sure what you are referencing here Pat. Happy birthday thought and Semper fi,

Jim

I was there too the most successful operation of the Vietnam war for the Marines the3rd received the Army Presidential Unit Citation for that Remember the Brothers that didn’t make it back happy birthday brothers

Thanks for coming in on this site and writing about it.

Semper fi,

Jim

Tomorrow is Veteran’s day and I will attend a small celebration in my little town and once be surrounded by those who know what it was like, WWII getting fewer each year, Korea, a war forgotten by most but never them, Vietnam, my war where I grew and guys from Dessert Storm, OIF And OEF, that are still in the news, I was with them too in 2008. Lots changed over all those years but one thing didn’t and will never change and that is the brotherhood of Veterans. So on this one day I will feel the warmth of a shoulder against mine too, and remember.

Yes, feel the warmth of me and others on here who join you in this time of strange diffident patirotism, when so much of what some consider the price of liberty has been either disregarded or forgotten.

We are banded together as we go through life, our exploits following us in our own collected memories but mostly not shared by a public that thinks a hero is something in costume, or that attemding a war at home as fighting it.

We have to be okay with this because the general public does not know what being a warrior is all about. They cannot know. To know is to have died or ciruculated among the dying and dead and survived, only to have survived and found to be

the product of something so unbelievable that it is not. So, for the most part, you and I and others on here, outside the band of brothers that comprise us, are silent as we watch…and wait…and hope that no more warriors have to be

made, no unwilling real heroes decorated…and no more of such young exhuberant souls crossed over.

Semper fi, and it don’t mean nuthin.

Jim

Powerful…I salute you sir…takes me to ‘don’t mean nuthin”.

Thanks for the great tersely delivered compliment. I much appreciate that and the shared understanding I feel emenating out from your words on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Happy birthday, Lt., from another of the walkers of the Valley. I’m still engrossed with your story and remembering more things as you tell of your things. Bit it’s all good nowadays. I haven’t the fear that I had there and I brought home with me, Somewhere in the 8 years of drink and drugs after, the fear and most of the nightmares left me.

Thanks, and Semper Fi!

Not many of us around…alive Andrew. I hope I am getting the descriptions of that place right. I see it all the time and dream it every once and awhile.

And now I write it hoping that guys like you will monitor and keep me on track. We are moving north, as the valley spread out before us…and maybe you will

recall those open fields of fire….sometimes good and sometimes so terrible…

Semper fi,

Jim

Lt claws is going to find out why you told them not to go. Too bad he will take a lot of good men with him. Hope he can register his position and give you a chance to help them with some friendly artillery fire.

The best intentions sometimes went to bad. ANd so many had such good intentions but

no knowledge, understanding or real experience. Like back here, everyone wants to give adice and then

have it taken no matter what the price. Just part of the human condition, but there many man died from

such actions…

Semper fi,

Jim

Happy Birthday to the Marine Corps. And Happy Veterans Day. Thank You for your service. And a great big Welcome Home. I wish that I could salute you one on one SIR. But this my little salute from all of us that will never meet you one on one. Thank You.

It is terrific to have you and others like you on this site. I know I will never meet but a rare few.

I can live with that because before I started writing this I kind of thought I was mostly alone. Not anymore.

Thanks for being and writing on here and saying what you are saying…

SEmper fi,

Jim

Dittos what Billy says. Too young to be in at the time but was reading every report in the papers at the time. All you veterans of Viet Nam were treated badly here at home by the radicals but there were some of us who saluted you and are proud of you. Semper Fi!

Many people treated us really well.

The worst treatment I got was by the Navy medical personnel at the hospital in Oakland.

I don’t know why.

One of the other veterans told them I was “Junior” and how awful my reputation in the Nam was.

One neighbor in San Clemente was awful until he moved.

Someone set off a quarter pound of C-4 in front of his house on July 4th, one year.

He thought it was me.

Occasionally, at a party early on or work somebody would have a passingly negative comment but I ignored that.

Most people were fine.

Like today.

Although I still have some C-4 left, just in case.

Semper fi,

Jim

Happy Birthday Jarheads!

That is all.

That is indeed quite enough SCPO!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim,you had me from the first chapter. My civilian jetliner landed a Tonsunute air base near Saigon. On my flight we were a mixed bag of FNG’s and troops returning for another tour. Being an E-2 Sailor i was put on a bus to the Annapolis Hotel where I was given my in country orders a couple pairs of marine greens (wtf I was a sailor)a pair of jungle boots and a M-16 welcome to vietnam. I spent my 12 months on the river south of Saigon as an Engineman working on river patrol boats PBR’s. We also listened to armed forces radio to get our news on what was happening in the bush. Great music piss poor news. Sorry for rambling but your descriptions dredge up long dormant memories. I can’t wait to learn the fate of the troops heading to Bill 975. Thanks for your story I tell every vet I meet to give it a read.

Respectfully

Third class Engineman

Richard C Linn

proud to be called a “river rat”

I cannot thnak you enough Richard, for the referrals and bringing in more vets. Lot of us out here but the number is becoming more rarified all the time.

Semper fi, and Happy Birthday. River rats were and remain so cool!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

Amazing,Beautiful, Powerful,and Emotional segment. God is definity with you on this purpose. God bless you with His strength.

Thanks Pebble, who sounds more like a boulder.

Much appreciate the blessing, as I go about living in my ‘church of the world’

since no local operation is going to have me.

Seems I have a tendency to fill up the room and that makes some uncomfortable.

Semper fi, and thanks for the great wishes and the compliment…

Jim

If it is you and God, that is enough and I will always be there in spirit and prayer. It is okay to be bigger than life because you are unique and special. That is why God chose you for this Special Purpose! God bless you and He loves you.

I know that is you Henderson and I love it. The Relentless Pebble. Thanks for your relentlessness.

I receive your messages and cannot help smiling…

Semper fi, and love

Jim

Happy Birthday, Brother Jim. Semper Fidelis.

Tim

Thank you Tim, and Happy Marine Corps Fucking Birthday to you too!!!! UuuuuuuRahhhhhhh!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

Happy birthday my brother!I’m sitting in a deer stand with my youngest son who is also a Marine. He’s home on leave for his wife’s grandmother’s funeral. I couldn’t pull my eyes away from the story long enough to even look out the windows for deer until I finished the chapter! Semper Fi and happy Veterans Day too!

Thanks Johnny Appleseed…I much appreciate the image of you guys sitting there and maybe whispering about the details laid out in the story.

Makes me smile big

time.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another good chapter…I can almost feel like I am there..Officers thought they knew it all. B. Co. 7th ID 2/31st…Korea 1969/70

Belief systems form up like ice atop the water of still lake, and they are hell to thaw out. In combat, they can

kill you real real easy…and others around you.

Semper fi,

Jim

Holy shit you hit the nail on the head about “belief systems”. The source of a great deal of modern misery leading right up to the present. Also why “Huey Cobras”? Thanks for the great writing. We call it fiction so that we can tell the truth.

The Bell AH-1 Cobra was part of the Huey family of helicopters. Hence the usage.

Thanks for the comment about belief systems. Inflexible as they are, in all of us.

Thanks again for the compliment…

Semper fi,

Jim

First off, I wish you and yours a peaceful Veterans Day! This chapter is brilliantly written! It reads like a cross between a fever dream and an episode of Mash! Well done Jim! Semper Fi!

Fever Dream, and Mash, now there is a thought picture to contemplate and entertain.

Yes, there is some humor in that chapter and a good deal of fever.

Thanks for that analysis and comparison…

Semper fi,

Jim

Happy Birthday, Jim!

Happy Birthday right back at you Michael and thanks for that on this day on this page…

Semper fi,

Jim

Outstanding chapter, Happy Birthday Marine, I️ spent the day with 4th grade youngsters so excited to hear about the Marine Corps, bright eyed, clapping hands, then on to dinner with Vets from Combined Action teams, grunts, jet jockeys – what a great day, and to end it with your artistry. God Bless Sir, America is great today as in our time, just have to look up and onward. Semper Fi

Harry

Thanks Harry for that felicitation and the followup with the kids. Great comment on a great day.

UuuuuuRahhhhh!

Semper fi,

Jim

Do not go quite into the night….

I don’t think we Marines ever have or ever will. “Attitude is everything”, seems I’d heard that a time or two.

Great spellbinding writing James, thank you for taking the time.

SEMPER Fi & Happy Birthday.

Sgt, think nothing of it. I do. I just write away and am doing so right now

if I can get the comments down to a reasonable number.

But I love the comments because it is not me writing and also

because I am always surprised, mostly with smiles.

Thanks for the compliment…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim… Could you clarify part of today’s story line for me? First, you wrote: “Clews, and both Johnson and Johnsen, led their unlikely collection of Marines and Army Special Forces back toward the rear CH-47, its tandem rotors already slowly turning, as if the machine had sensed the approach of the combined arms outfit.” And then shortly after LT Clews departed on the CH-47, you wrote: “The Stars and Stripes personnel went face down on the concrete to wait out the wind storm with the Special Forces team surrounding them.” Did the SF team split up with one element going to Hill 975 with LT Clews and the remaining team members remaining behind with the Stars & Stripes group? As a former SF officer (1966-77), I am skeptical that any operational SF team would be assigned to provide security for a Stars & Stripes junket. Just wondering…

Stars and Stripes flew in with no security other than the Cobra gunships.

Security was expected to be supplied by the unit they were flying into.

I think. I never asked. I just presumed.

The Special Forces unit, slaved together with Clews men, were the combined action team and,

although they must have had a connection to flying in at the same time as Stars and Stripes

I never asked about that either, or found out for that matter.

Thanks for the in depth analysis and putting it up on here.

Very cogent and you are making me think in detail…

Semper fi,

Jim

So some of the SF team remained with you and the Stars & Stripes group?

No, they all left as part of the combined action group.

The Stars and Stripes people depended on the Cobras

and existent unit they were visiting to provide security….

Semper fi,

jim

If all the SF team departed with LT Crews on the CH-47, then you’ll need to edit the following sentence: “The Stars and Stripes personnel went face down on the concrete to wait out the wind storm (with the Special Forces team surrounding them).” Need to delete words within parentheses.

Being done right now. My mistake….

Thanks for the edit.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks Steve.

Correction made.

Semper fi,

Jim

While we steamed thru a thphoon, my shipmates and I were on edge so we wouldn’t lose the main propulsion engines when the props came out of the water when one of those big waves passed under the ship, but nothing compares to the conditions and combat you men experienced in the A Shau, then you get a visit from some knucklehead Major that has no clue, personally, I’m glad they all left and that your men appropriated some of their supplies, nice work by the Gunny!!

I really had a hard time with the supply theft thing. Because we were all in combat together and in my heart I just knew that those guys were flying to die on a hill and would need whatever they had. Tough stuff when you’re in the field, at least it was for me. Thanks for the comment and for sharing your opinion about that sensitive issue. But then, you don’t know what comes later….yet….and I dod…

Semper fi, and Happy Birthday…

Jim

Stay he hissed .Sounds like the gunny kept a bull dog from tearing Clews to shreds .Lt, the first of the segment had me mad and the last very sad .You definitely have a talent . Semper fi

Thanks Roger, much appreciate the compliment and the sentiment. Happy Birthday!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

HAPPY BIRTHDAY USMC! Thank you Veterans for our Freedom !

Thanks for the Happy Birthday. I will tip up a hot Dr. Pepper (the Gunny’s favorite drink back home in New Mexico) and celebrate the event.

My wife isn’t too big on it, though, having done the Marine Corps thing on the sidelines of pain for so long….One day I will publish all the letters home I wrote in that muddy hell of a valley, since I have them all (save at least one that part of the envelope was in that amulet).

Semper fi,

Jim

Wow! Another great chapter. I have not commented in a while but, have been with you the whole way. Many (including myself) have commented on your ability to put us “there”. It really is that good. I have a whole new understanding about things that happened there and were never taught or portrayed in the fashion you present them. I am reminded of Wolfgang Petersens “Das Boot”. I read the book before seeing the movie. Both are 5 star. It was a very long book and all events were true. It was filled with boredom and terror…just like it was. When I finished the book I had a whole new understanding and perspective of how it affected the whole crew. They were just trying to live through it like everyone else. It is your ability to convey the emotions that make it special. I have the same feeling that this will happen when the end to the 3rd 10 days is finished. I can only speak for myself when I say I have become attached to the Marines you are with and realize nothing is for sure. Anything can happen at any second. BTW, When you post these in the early mornings I have been late to work because I have to read them first. It’s okay because I am self-employed and give myself a “warning”.

Thanks Lee. Much appreciate that lengthy and deep comment. A lengthy comment of intellect and great compliment, I might

add. I cannot thank you enough on this the birthday of the Marine Corps. I felt so distant from while I was in and only really a

close integrated part of after I was out…go figure.

Semper fi,

Jim

Lt as a door gunner in an out of hot lz’s you bring me back to thoughts of friends lost and found .days survived and given to to the sands of time only to return in the darkness of night when peace refuses to enter a tired and weary soul .semper fighting my friend

I don’t know whether bringing you back is a good thing or a bad thing. I don’t know what to do about that.

I just keep on laying it down all the way through that relentless bloody valley…

Semper fi,

Jim

Outstanding segment once again James…your writing makes us all hear, see, smell, and feel like we are right there beside you… the imagery that you paint is just outstanding…and the emotions…fear was ever-present and you are still not giving your leadership abilities enough credit…I, like everyone on here, await your next segment…and Happy Birthday Marines from an old Army guy…and Happy Veterans Day…

Happy Birthday Marine! Thanks for the great compliment and thinking better of me going through that than I did…or really do.

Semper fi,

Jim

Outstanding chapter Lt, & Happy Birthday to you,our Brothers & our Corps!!

thanks for the compliment and the celebratory Happy Birthday. Funny, that celebration, so unique to the Corps.

Semper fi,

Jim

HAPPY VETERANS DAY GOING TO SCHOOL TOMORROW FOR MY GREAT GRANDSONS . I am there Veterans Day Veteran

Thanks a lot Fred. Same to you and all the guys and gals on here….Tomorrow is the Marine Corps Birthday too! UuuuuuuRahhhhh!!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

God Bless. Semper Fi

Thanks for the simplicity of that compliment…

Semper fi,

Jim

Semper Fi LT. 242 and going strong.

You got it Terry….all the way, up the hill…

Semper fi, and Happy Birthday….

Jim

Man I’ve known plenty of asses, but you and your men have come in contact with more than everyone should have! Oh my now I don’t want to wait, for more. Ok I well do it.

There were so many guys coming from the rear area being given totally bad data.

They were set up by the mythology of war so powerful in almost every culture.

Thanks for the comment and your accurate assessment…

Semper fi,

Jim

When you write like this, it’s like Mozart with the music leaping from his fingers, no thought patterns or processes in play, just the melody demanding to be released, to be heard. In your case, to be seen and read. “I was among Marines, and they’d been consigned to their valley fate long before me, and although they’d likely suffer the same fate as me, they’d not go quietly surprised but deliberately kicking and screaming into the night. I watched the light wind play across the fronds of distant bamboo, waving across the tarmac at me like a bunch of thin overly tall stick men. I knew I’d fall instantly asleep once I was able to get back into the cave, like Zippo and Fusner inside. Nguyen squatted not five feet from where I stood. We’d exchanged our usual secret and knowing look. It was all either of us needed of one another, to let each of us know that anything either one of us needed from the other would be provided.”

These are images only the dead-tired and danger-numbed brain can conjure up, and the vividness of them are impervious to the ravages of time. Truly a stellar chapter, Strauss.

And, old traditions notwithstanding, it’s still fitting to wish you a Happy Birthday, Marine.

Conway comes back. And does he come back when he comes back. Now that is one hell of a comment and I cannot thank you enough for the praise

and the compliment, not only by repeating the sequence but by giving your opinion about its origian. Thank you John Conway. You make my heart soar like a butterfly.

Semper fi, happy birthday and thanks for being my friend, as well as brother,

Jim

I’ve never been “gone”. I’m on to these new chapters like stink on a skunk as soon as they come out. Some where along the line, some of my replies got zapped off into never-never land while “awaiting moderation”. I’m as hooked as the rest of your “lifers” on here.

SF

I answer all comments within days. Some real quickly but you have

to remember how many I get and how long it takes which takes time away from writing the segments.

And the rest of my life, which I really do have…in spite of how fucked up I may or may not be.

Thanks for writing and complaining. I need that motivation too!

And the huge compliment with the complaint, of course! Smile.

Semper fi,

Jim

Damn John Conway I thought only James had this writing stuff so pegged to the ground. You sir in that comment touched me placed I forgot I still had. Thank you and Mr Strauss for lighting a path I mainly walk the dark of the night. SEMPER FI MARINES, HAPPY BIRTHDAY and a REFLECTIVE VETERANS DAY to all hands on deck.

Thanks for that comment. Conway is something else again when it comes to intellect and life experience.

Wonderful man and all you have to do is read a little of his stuff to know that.

Semper fi,

Jim

Nice omage to Dylan Thomas, “Do not go gentle into that good night.”

I didn’t think of that but should have. Thank you for getting the attribution right.

Semper fi,

Jim

What is it about Marines? Regardless of the misery, mud, rain, lousy chow, bad water and race divisions, ‘a sheet of steel awaited the enemy should he try’. Where do we get this ‘never give up’ attitude’? Somewhere in boot camp it seeps into every fiber of our being.

Don’t know the answer. Nobody knows except maybe another Marine.

My dad knew it at Tarawa and Saipan. YOUR Marines and you LT, knew it in the Au Shau.

Great read, Jim. Semper Fi

There is sno doubt that there is something mystically special about Marines.

Like you, I don’t know where or when the magical change occurs.

Once it’s in it does not come out.

Amazing, really, and different among all the worlds military services.

Semper fi,

Jim

There certainly is something magical about Marines, especially since my oldest grandchild is one, Lauren graduated from Parris Island on 01 September, did her MCT at Camp Geiger, and is now at Camp Johnson for MOS training. She is already trying to get ‘downrange’,which is really upsetting her mother but I think I understand. Once upon a time I was afraid Vietnam would end before I got there. Who knew it would drag on long after I was through there. So, this thing I just read is a chapter from an unfinished book? I very much enjoyed the authenticity, it seemed ‘real’, I’m gonna have to find the other chapters. Happy Birthday, Marines, ands, if I may, Semper Fi!

The First Ten Days of Thirty Days has September has 39 chapters.

The Second Ten Days, almost done, will be over forty…so you have quite a few reads in front of you.

All of it is up on the Internet site for free if you want to read segment by segment.

The First Book is out on Amazon and the second will be out in hard print by the end of November.

Thanks for the compliment and for writing it up here…

you will be in good company if you come back here to read and write some more.

Mostly real guys and gals…

Semper fi,

Jim

The part where two Marines physically had each others backs brought back a telling of a Marine’s similar experience. This Marine came in as a FNG, 18 yrs old. Another Marine picked him as Platoon radioman even though he had zero training. Both the men are still alive and living their lives almost back in the World, like yourself. They meet in person every year somewhere, I guess something that helps them believe they really are in the real world. My friend speaks of sitting back to back in a small hole every night, he never sleeping, but likes to remind his friend that he slept while he was off watch. Lots of good natured talk about man crushes but only they know what that forced closeness really meant and still means. The story still has a life time of days to grow, but I for one will hurt inside if anyone’s premonitions are realized.

Your mission is still being accomplished by the powerful storytelling we are all being allowed to see even as it is written. Poppa J has probably run out of superlatives, so, damn good vignette LT, hope we see the next days very soon. Poppa

Working to get another segment up for Veterans Day Poppa. tomorrow will be a work day for sure.

Friday. Hopefully I can hide myself away far and deep enough to get the time without people coming to ask me what I’m writing!

Thanks for caring and thanks for the comment you made here about the radio man and his C.O.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks for another excellent read, LT. “PR” visits from REMF troops, especially for photo ops, always pissed me off. Glad you are coping!

I was not sure how many units had PR visits. Seems to me they came out to decimated units

in order to get the real ‘feel’ for the look and touch. And then they stole those things and lied

about the rest…after quickly getting the hell out of there, of course.

SEmper fi,

Jim

Probably one of the best segments yet… if I ever get to Lake Geneva again I wold like to stop by and shake your hand and thank you for bringing me that far into the A SHAU valley and what it was like to be in the company of such great soldiers.

Thanks a ton Steve and you will be most welcome here. I usually sit in the back corner of a coffee shop and work silently away, but man will I make

the exception to see anyone who comes through this site. It’s happened twice and it was wonderful. There are some real men and women on this site and it is a wonder

to meet them im person, or even here online. Never expected this.

Semper fi,

Jim

Hey there LT. I haven’t commented in a long while just wanted to let you know I haven’t missed a story yet and still enjoy your writing very much take care and thanks once again thank you and everyone who served for your selfless service!

Thanks for coming back in Josh. And thanks for that neat close to vets day compliment!

Semper fi,

Jim

I agree, a very emotional segment. I’m an artillery vet and spent a lot of time in radio contact with the infantry but your writings help me better understand what they were going through. God bless you!

It was an emotional time, although I am not always effective in getting it down on paper.

Thanks for noting that and for the compliment you wrote about my accuracy of putting it down.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another excellent chapter Sir!! I spent my 20 years in the Army half active duty and half in the SC National Guard. It took me 15 years to make E-6 (Staff Sgt. in the Army) and that is what I retired as. Mostly took so long due to officers like your Major there. I did find that in the Guard the officers tended to be more open to listening. Anyway, the officers I did like, respect, and get along with are much like yourself, You remind me of a few in particular. Those were and are men who I would follow to the ends of the desert.

Thank you for doing what you did, the younger generation of Soldiers and Marines remember and respect.

Andrew Luder (SSG Army Ret.)

122nd Combat Engineers

2003-2004 Operation Iraqi Freedom

Thanks you most kindly Staff Sergeant. My real hsart is with the non-coms becuase it is non-coms that kept me alive.

That taught me for real. That made me realize that were were Marines together not officers and enlisted apart.

Sempper fi, and with great appreciation…

Jim

Simply outstanding writing. Thank you for such a heart wrenching story.

Thanks Jack, your compliment is really great to read and expecially the fact that you wrote it on here for all to read.

I write on, with the fuel of your comments powering me through…

Semper fi,

Jim

Staggered as usual. Bounced around physically, mentally and emotionally like a freaking ping pong ball doesn’t half say it. One begins to get a pretty clear handle on who’s walking out. Only feel for the guys they drag into their follies. “Cluster fluster”, like I posted last chapter.

Thanks for the compliment and the writing it up on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jeezus Jim another gut punch , so Clews is really clueless ? I am keeping my fingers crossed that Fusner could not accurately predict his own death

Clews was just typical, I figured out. Talked to by the guys in the rear, he bought into a mythology that wasn’t true.

Who was going to tell them in the rear, sure as hell not the guys who might come in from combat.

Thaks for the comment and the compliment…

Semper fi,

Jim

Simply amazing writing. How you controlled your temper is beyond me. Realizing the respect you earned from the Gunny and your troops is hindered by exhaustion. Fate will take its toll on Hill 975 of the FNG Major and his men.Thank you for another riveting installment. Waiting to purchase the Second Ten Days.

Trying to figure things out while sleep-deprived, hungry, thirsty and in total fatique was the toughest part.

How do you think under such conditions, much less pay attention to the details that might kill you?

Semper fi,

Jim

Another link in a fascinating chain…

Still have a mix of “Crews” and “Clews.” Which is correct?

” I laid down next to Fusner, uncomfortable to be needed by my radio (officer) whom I thought of as being so tough.” Did you mean “operator”?

Wow, went through 3 tines looking for all the CREWS.

Fixed now, thanks.

And I am next to my operator.

Semper fi,

Jim

Riveting, and I love the comments also.

Thanks for that one work compliment and thanks for liking what the vets put up here in the way of comments. Some real deal guys come aboard and

let it all hang out. I never figured when I began.

Semper fi,

Jim

Damn Lt, been reading from the start. Lots of memories and surprisingly, healing I think. Thank you for this and keep them coming. Now I must find more tissues. Semper Fi

Thanks Greg, I am working on getting it all out here, for the first time ever.

Cathartic but at times painful too. Still, I thought and now really believe I have to finish.

Semper fi, and the thanks for the compliment…

Jim

“He was kidding,” not He’d was kidding as printed. Paragraph where Gunny was leaving to pick up bodies in the 46.

Story just keeps getting better, thanks.

Thanks for input, Robert

Corrected

Semper fi,

Jim

Got it and will make the changes. Thanks for the editing help, and the compliment at the end!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, Welcome home. Hope these are not too late for first edition. Dave.

while the (technician) filmed repeat takes from (their tripods). => (technicians) or (his tripod)

=> in 2 places the word tarmac is used which is asphalt, when this runway is probably concrete.

Thanks again David,

Really appreciate your help

Going to leave Tarmac as it is often used for “runway” regardless the material

Semper fi,

Jim

I can visualize the brass in the rear sitting around a table drinking whiskey not knowing shit about what’s really going on, but want to talk crap about you. Bet there would be a lot less names on the wall if there were people that really knew what they were doing.

I never got to know. The brass in the rear included battalion command. I would never had believed that because at Quantico it was always assumed that

superior command was right there in the field with you, only a stones throw in the distance, observing everything and sending out commands. The reality

was beyond shocking. The radio traffic with battalion, in my circumstance, was less than with the supporting artillery batteries or with air support.

I had a one on one relationship with Russ back at 2/11 in Ah Hoa and with Cowboy in the air. I had none with anyone, not one single soul, back at battalion.

So, I don’t know what the hell they were doing, except for certain avoiding coming out with us….

Semper fi,

Jim

The few typos I noticed have already been addressed but, damn! Fantastic writing James, makes me feel right there!

Thanks for the great compliment Joe. Keeps me going and makes me smile…

Semper fi,

Jim

The way you write, I can almost see, hear, taste and wear your words. Keep em coming!

Thank you Brad, as many times the next segment gets written on the ‘fuel’ of your compliments and comments.

Your comment is one of those motivational pieces. Small and short but powerful…

Semper fi,

Jim

This a great story although sad. But explains a great deal about Vietnam. My uncle was a cobra pilot, pushed in just about like you … ” can you fly?” “Then get in”

I really enjoy your writing

Thanks Greg, I most apprecizte your liking the writing. It is a sad story in so many places, but it’s also a story of going at life as it comes

at you. Head on when necessary, on the oblique and by the enfilade or in retreat when necessary. Is there heroism and valor is having no place

to run away to? I don’t know. All I had was my battered, bandaged, broken and FUBAR company of mixed up kids.

Semper fi,

Jim

Lt. Much as I admire Marines, I have to wonder at their Officer training. You seem to have been the exception rather than the rule. Not one of the Newbees sent your way has asked for a “Situation Report” nor attempted to “De-brief” you for the intel you and yours has gained so far in this operation.

I don’t think any officer training of any service anywhere teaches a new officer to come in and get advice on anything except from the commanding or a superior officer.

There’s nothing in the manual about when there’s no senior officer. A new C.O. might be taught to counsel with his command post team but you have to remember what my

reputation was when I went in and then after I was there for a while. Pretty bad. So, the lack of wanting to hear from those already on the ground was sort of forgiveable.

And, in fact, those that failed to do that paid the ultimate price. How can training commands understand anything about combat when so few survive it in any condition to report

back?

Semper fi,

Jim

well said. i concur.

Thanks Glenn!!

Jim

Another great chapter, LT. Semper Fi and Happy 242nd Birthday tomorrow!

I wish the celnbrtion of the Marine Corps Birthday was different. I would go if it was different. I do not want to go for LeJune’s address being read, or

honoring the oldest and youngest Marine or any of that crap. I would go to hear Marines stand up one after another and talk about what it means to be a Marine

and what it was like when they were still active. I’d go to sit at dinner tables filled with the active young Marines sitting among the old guys and gals.

I’d go for that. As it is, I will be here, drinking a toast of Dr. Pepper, heated, just the way the Gunny said he drank it back home. Uuuuurah!

Semper fi,

Jim

You can do both, Jim. Tradition is the bedrock that makes Marines Marines. Without emphasizing that to the new ones, we would just be another bunch of guys with guns. The traditional ceremony doesn’t take that long, and a lot of valuable lessons and maybe-even-true sea stories get passed after.

Happy Birthday, Marine!

Too true, and I should have not written on here what I wrote. I am such an iconoclast and non-joiner,

mostly because what I join does not join me back. But that’s my perspective.

Thanks for the course correction…and setting things straight…

Semper fi, and Happy Birthday,

Jim

There comes a time when the battle is done and we all become one as comrades in arms. We paid our dues both in life and in death and have earned a cherished peace and rest.

With that said, I salute all of my brothers in arms and wish you all a happy and peaceful Veteran’s Day, job well done!

Semper fi James

Thanks J. We did indeed pay our dues, so to speak.

But the dues just get you back into the world, they sure as hell don’t secure a place of honor for you.

For example; I have a Purple Heart license plate.

The local newspaper ran a story alleging that my plate might have been attained by fraud.

That was not true, of course, and they should have known that since it takes a lot of the right paperwork to qualify.

But there it was.

Real life, right here in little old River City.

Semper fi,

Jim

That is a shame James, but that is what you get in a liberal community in this country. I live in a predominantly GOP county, where all veterans get treated with respect and thanked for their service.

I live in the most conservative county in Wisconsin except for Waukesha.

Just the way it is. Semper fi, and thanks for commenting on here about this, as usual J….

Jim

Hey Lt. Can sense the maturing of the young man coming to the fore in this piece. Guess most of us have faced it at one time or another. The consequences, however don’t come with such rapidity to most. Rocky road ahead, or so I sense. Take care Lt.

I never could ‘take care’ in the valley. I tried hard enough. I wanted to stay inside that hole in that czve

or anywhere but out exposed to the weather, jungle and enemy…or even my own Marines. There was not place to hide

for very long. So I did what I had to do…and it was so fucking hard to do. Fusner cried that night and I saw it.

I cried that night and nobody saw it. It just had to be that way. Hard.

Semper fi,

Jim

What a psychological gold mine, when contemplating the differences between reality versus mythology. On one hand, we have the ranked newbies who have never been tried in the bush, verses those who were tried and true. The mental and knowledgable differences between the two different elements, were as vast as the valley. To add to the delusional scene, was the world of fantasy that was represented by the Stars and Stripes crew. Each communicated from entirely different prospectives and yet, were all part of the senseless war in a moment of lost time.

As one continues to read this saga, one can understand why junior continues to doubt himself, is filled with fear and has accepted his fate to die in the hell torn valley of the A Shau. His only counselor for understanding, lies with the Gunny who says little and is often questioning junior’s actions, adding to the immense self doubt that junior is always struggling with. Because of junior’s personal struggles, he fails to see that of the others that surround him. His NCO’s that fail to follow orders for fear of being killed. A weeping and crying NCO, who is caught on a broken bridge and fearing for his life as the enemy is shooting at him. Then his ever present radio man beside or behind him to serve his needs, gently crying over a premonition of death. They all showed signs of fear that junior did not see and was afraid to show himself. Yet it was there, clear as day, every day and night.

Yet, each and everyone of those marines, had the courage to face down their individual fears and overcome them in victory and in death. Fear is the beginning of courage, not the lack of it!

As usual J, you reach right into the very guts of the segment, haul out the psychological entrails and then smack them down upon the cold

fetid soil of human discontent. Yes, to all of what you said, not that I could see it before you wrote it. I cannot see when I am writing this.

I simply sit here and the words come, flowing out beyond the experiences. I see things. I still ‘see’ Fusner and his tears. I still see that

cave and looking out through the slit onto the surface of that raised muddy river passing by so fast. I feel thta air and smell that combination

of smells I’ve never experienced again, but I know that combo is still out there somewhere. Thanks for the unbidden unwritten but oh so evident compliment

in your words.

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

Sometimes you just leave me with nothing to say, not even the wise crack I usually have when there’s nothing else. Reading your viewpoint makes me wonder about what the grunts were thinking. Reader comments fill in part of it and what you wrote about the contact with Fusner spoke volumes. Thanks, Jim.

I know you. You don’t have to say much. You ARE much!

Semper fi, and thanks, as usual…

Semper fi,

Jim

Keep at it Lt. I know some hard chapters are still ahead. You told him not to go. All you could do. It don’t mean nothing.

Don R

Yes, Donnie, I did tell him not to go. But the Gunny stole all their shit.

What if they’d had all their stuff up on that hill?

Segment to come…

Semper fi,

Jim

Did the Gunny really steal all of their shit? Considering what the Gunny knew about the bush and about Delaware, were those really his intentions or was he merely looking out for his company, that would have to rescue what was left of the troops that were headed for the Hill?

The Gunny made it very evident to you and others, that Clews and his men were headed for disaster. He was so convinced that this is what would happen, that he claimed to have lied his ass off about needing you to stay in the rear with the rest of the company. He merely procured that which was needed for his company to survive.

Gunny also saw the air support that Clews and his men had, so probably figured they would not miss some of the supplies which he procured. He was also smart enough to know the Clews, did not have the manpower to protect any command post that he intended to set up, once he reached his destination.

Last but not least, any good officer would have checked the necessary supplies needed to complete his mission, before departing. Midnight requisition was not uncommon in the military.

Clews started back from that chopper, angry as hell, no doubt. But then he thought better of trying to get

Army guys to come out and get the supplies back from grizzled Marines, probably. He might even have gone on

thinking he could cover the pilferage with a quick resupply the next day. Combined operations were usually lavishly

supplied and thought of, even if they seldom worked.

Semper fi,

and thanks,

Jim

Another great segment LT. All grunts can empathize with the terrible living conditions and the green FNG officer’s ignorance of the reality of war.

Thanks for the compliment and the encouragement and understanding.

It was indeed a very strange time, but apparently not as uncommon as I once thought before beginning to write it and put it up here…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, it occurs to me that all the characters in this book are not wearing uniforms…Marine or NVA. The river and the rain are very much antogonists in the story…over which you have no control. I know you don’t often feel like a hero, but that is just what heroic characters do. They wage war against foes over whom they have little to no hope of defeating.

Don’t know if you intended it or not. If you did, you’re damn good! If you didn’t, then that’s even more creative genius…unconscious. You have a great talent for writing dialogue that just draws me in…I feel the wetness, I smell the decay, I hurt when you hurt. No way around it, this is one painful story to read. I can’t even begin to know how much it hurts to write it!

Thanks for, first, standing in for me while I got a 2s and played football and learned how to teach. Secondly, thank you for allowing me to hurt with you as you write this. It is an honor.

Bobby. Thank you. A big thank you. We all wore uniforms. We wore the Marine utilities,

mostly herring bone from Korea or the plain green stuff iwth the black patch on the left breast.

They wore black silk and cotten things, sometimes with funny little open ‘coats.’ In reality, with the mud

and the mess of it, we all wore this sort of brown mixed mess of attire. We had the flat ‘boony’ hats, tied

bandannas and WWII helmets with liners and canvas covers (brown or green side out). They wore bandannas and

sometimes the pointed ‘lampshade’ rice hats of the lowland farmers. Sorry I have not done a good job about

describing that. Hope it helps. We all wore mud

Semper fi, and thanks most sincerely for the depth of your compliments. Received!

Jim

Semper Fi, that all i can say,i saw the vslley,and walk on the ferns

Yes, the firms of the valley north. Interesting that you would mention them. The dark green and the nearly chartreuse stuff

of the early shoots. Thanhks for commewning here and being one of us.

Semper fi,

Jim

good read LT> most people will never understand what we went through. we endured the boiling heat the tough terrain with 60 pounds of weapons and gear. we lost 20 percent of our body weight while in the bush. we slept on the ground under makeshift poncho hooches we took them down in the rain because they shined and became a targets. we never got more than a hour or two of sleep for months at a time in the bush.A break consisted of four or five days in the rear. and we are here today because we covered our fellow troops. all I can is say is its kind of hard to get excited about tales of Woodstock. thanks LT. for showing people what it was really like.

Thank you ever so much for the compliment and for writing about what it was really like.

I don’t know how we did it now.

The burden was so fucking huge.

Semper fi,

Jim

“”The day was dying as I stood there…….wild Bong Song river.””

”

Between the beginning and the end of this sentence ….you could fill another book… Pure magic….

Gunny made promises and told lies to the Hill 975 boys…..just to convince them to leave without you….He did what he was supposed to do…protect his Officers and men….Most of the Gunny’s I knew could have walked on water and I wouldn’t have been surprised at all.. Get some sleep “Lt”….yer gonna need it….I have a feeling that “Shermans march to the sea’ might have to take a seat in the bleachers…. “Delaware’….here we come…. Semper Fi……..(and by the way…Happy Birthday tomorrow!! )

I went back and reread that Larry, because of you. I read it and wondered who wrote it.

Like it had not come out of me.

With my eyes closed I imagined that passage, being back there

and trying to relive but not trying to really relive. Thanks for that deep compliment.

Yes, Delaware is up ahead and the pace is not about to slow at all….

Semper fi,

Jim

reminds me of the joy of receiving a letter from my honey after I had set a base record of 87 days for not receiving any mail, even “occupant”, only to rip open my own “Dear John” letter…..damn

Man oh man, a dear john letter after 87 days.

I don’t know if I’d have survived that, if I’d made it for 87 days, I mean.

Thanks for revealing that. I love the ‘occupant’ part….

Semper fi,

Jim

Awesome God given writing. Tears flowing here. Thank you for telling your story as it really was for you and many others. God Bless you and you are doing God’s Great Purpose for you. Praying for you everyday for strength in the telling of your story.

Love,

Nancy

thanks Nancy for crying in the right place…and letting us all know it.

On this day, me to you….semper fidelis and God bless you…

Jim

I waited with great anticipation for this portion. I knew that the Major was going to be a problem, but I still got angry when I read it. You showed great restraint by not punching him. Gunny obviously liked or preferred your leadershipy, to go to bat for you like that. Keep writing. I plan to buy your book for some of my ex military friends when finished.

Thanks Cathy, much appreciate this kind of comment coming from a woman. Not too many women readers of the work although so many women

participated in the war in different functions (wife at home only being one of them).

Semper fi, and also thanks for passing it on…

Jim

Jim, another mesmerizing chapter. Hope the next is coming quickly. But I’ll be sorry when it’s over. Your writing is too compelling.

Noticed one typo: I stopped in my tracks and turned to face him. I wanted to yell something back at him in anger but then saw that he was smiling a big smile. (He’d) was kidding.

Should take off the apostrophe & the d.

Thanks Kathi, for the compliment and the editing help.

Semper fi,

Jim

Well done as per your usual standard. Far be it from me to criticize an actual writer, but this just really awkward: “We’re going to be going to bag that whole lot up, and then get the hell out of there if we can.”

Leave out a “going?”

Thanks Tom for the compliment and the editing help. Rewording as I write this…

Semper fi,

Jim

lt you wright were it feels like we are there. been with you since day one. very good chapter keep em coming thanks

You are there with me in these books, or at least so I hope, and the verification that you are in the right place,

well, that’s all in the comments on here. The real guys are the main audience and they’d be long gone if this wasn’t real as hell…

And hell…indeed.

Semper fi,

Jim

“you’re damned will going to look and act the part when we meet again.” should read you’re damned well going to …

“He’d was kidding.” should read “He was kidding.”

Thanks for the editing help Albert…and being part of that team…

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks Jim

You are most welcome Don, and thank you ever so much…

Semper fi,

Jim

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vDuDZQUkwrA