“Love child, never meant to be. Love child, always second best.” Brother John, on Armed Forces Radio, presaged the lyrics in his deep baritone voice. A different voice introduced John without actually introducing him. Was John really in Nha Trang, spinning a platter with the latest Supremes’ song on it? The song was as far and distant from the coming dawn as I was from any kind of reality that I wanted to be a part of. I got up, although I could not remember sleeping like I’d been so accustomed to doing back home. I’d merely missed a few hours somewhere. I didn’t feel like I’d slept or was waking up. The sounds of morning gentled their way into my recovered ear canals. I knew I needed some kind of ear plugs for night combat or I was going to go deaf, but then when I thought about it further, I realized that I’d be deaf anyway with the plugs in and I could not afford to be deaf in combat any more than I already was when the firing began.

I poured water into my helmet, setting the liner aside until later. I shaved carefully with no mirror and a mechanically operated double edged razor. The edge was brand new but not sharp. I worked at it intently, trying to forget where I was. I took off my utility top and washed under my arms for no good reason I could think of. I brushed my teeth, spit out the water and was done. I got dressed for the coming day, put my helmet together, strapping the rubber band Fusner had given me around it. Now I had repellent right there at any time anywhere. My utility top still had some wrinkled starch left in it which had nicely absorbed now blackened sweat marks. Shirts or tops were not called that in training. They were called blouses, but I could never think of them that way. Folding up the bottoms of pants, called trousers, at the bottom was called blousing too, for whatever reason.

The day was going to be partly cloudy with the sun soon coming up over the top of Hill 110, our target or objective. I had now seen the hill that had become famous a year before for some attack that had been punishing on some other unit.

I stood up, got my gear together as best I could, and went to work brewing some instant coffee in my canteen cup holder. I was out of cream and sugar again.

But maybe there were packets in one of the Ham and Mothers I’d have for breakfast. The Gunny came out of the heavy brush nearby as I ignited some Comp B. A big black Marine wearing a bush hat followed him. Bush hats were flattened soft things that would also look right at home on some sailor’s head off the cost of Maine, except this Marine’s was green. The black Marine wore no rank, which I was now accustomed to. He also wore a utility top, but with the sleeves cut off all the way up to his arm pits. His boots were the jungle boots issued back at Battalion, if I ever got back to Battalion. The most distinctive feature of the Marine was his purple sun glasses. Big twinkling lenses surrounded by gold frames.

“Sugar Daddy, I presume,” I said, looking up but making no attempt to move from my crouch over the small fire.

The Gunny squatted down, as did the big Marine.

“You’d be Junior,” the man said with a giant smile, revealing snow white teeth except for one centrally located shiny gold one.

I made no move on the outside at the use of the nickname, glad I’d already heard it. I brewed the coffee, stirring slowly until it was hot enough.

“Some coffee, Gunny?” I asked, looking the Gunny straight in the eyes. I noticed that Fusner, Stevens and Nguyen had retreated into the background completely.

“Bracelet,” Sugar Daddy said, pointing at my right wrist. “Don’t give those to nobody. Elephant stuff. Big mojo.”

His voice was as deep and beautiful as Brother John’s, I noted. I drank some coffee, wondering if I was supposed to say something, complain, question or whatever. I could think of nothing that wouldn’t create instant conflict. If there”s anything I’d learned at lightening speed, it was that training and experience were no help at all. I didn’t know anything relevant except what I was learning day by day, as long as I lasted.

“I’m platoon commander,” Sugar Daddy finally said into the silence.

“Yes,” I answered, drinking more coffee, but not tasting a thing. For some reason this meeting was vitally important, but I didn’t know why. I waited some more.

“Unit’s doing fine,” Sugar Daddy said.

Fine. The Company was losing five percent of its strength per day, and that was just the dead. There were no officers. There’d been no way to call in accurate artillery or even read a map before I showed up. And evidently there were as many deaths caused by friendly fire as from the enemy. The Company was doing fine? What did he mean?

“Why are we here?” I finally asked, deciding to show my ignorance.

The Gunny refused to look at me, instead taking out his K-Bar and poking around at the remains of my little fire. Sugar Daddy took out a cigarette and lit it. It was no ordinary cigarette. It was pungent smelling marijuana or maybe something stronger. He blew the smoke gently across the fire. I didn’t blink or cough.

“Tom says things can stay the same,” Sugar Daddy intoned, blowing more smoke, as if to accentuate his message.

“Who’s Tom?” I asked, surprised.

The Gunny waved one hand upward a bit. I realized that Tom was the Gunny’s first name.

“Okay,” I replied, drinking some more coffee.

“Okay?” Sugar Daddy asked. “What’s okay mean?”

I drank more coffee, thinking about the fact that there was no safe or comfortable place the conversation could go. I was living in some anthropology experiment where the apes had been replaced by Marines. Different sized and different colored, but apes nevertheless. Sugar Daddy was applying his somehow attained Alpha Male status and I was supposed to either meet him right now in combat or demonstrate that he was the alpha and I was a lower class male.

“Benton Harbor,” I said, putting my coffee down and looking as far into the distance as the jungle would allow. “Do you know where Benton Harbor is?” I asked.

“What’s he talking about?” Sugar Daddy asked the Gunny after almost a full minute of silence.

“I don’t know,” the Gunny answered, finally looking up at me. He frowned but said nothing more.

“Well, I don’t give a shit about no Benton Harbor or any of that,” Sugar Daddy said, forcefully. “I’m running the Platoon and if you’ve got questions about that you can ask them here and now or forget it.”

I took the few seconds I had to think about how out of control and totally lost a Marine company had to be to have come to such a desolate unruly place where every vestige of the training and spirit of the Corps had been lost. Marine training had forged me from a middle class kid doing okay in school and sports to a physical specimen acing every test they could throw at me. I was a Marine through and through and I knew down in my bones that another dead Marine officer was going to be of use to no one and nobody, especially me. I was probably dead anyway but I deserved to be killed by the enemy, not my own.

“Okay,” I said again, this time looking at the man’s purple sun glass lenses. “What position does your platoon hold in the company? Where are you bivouacked from here, grid-wise?”

The Gunny jerked his head up and I felt someone hidden in the jungle behind my hooch inhale sharply. I knew it had to be Fusner.

“We’re done here,” the Gunny said, getting to his feet. “We’ve got a meeting to decide about Hill 110, medevac coming in and resupply. Let’s move on back to our units.”

“Three days in country and he’s nuts,” Sugar Daddy said to the Gunny in a loud whisper, intended for my ears I was certain. He stood slowly. “He’s your problem unless he becomes my problem,” he said, speaking in full volume.

“The fourth day,” I said, not moving or looking at either one of them. “It’s my fourth day in country.”

They walked off without anybody saying anything further. I listened to their boots making sucking sounds in the mud until they disappeared into the lower jungle ferns and fronds. When they were gone my team reappeared out from the same undergrowth.

I pulled back into my hooch thinking about resupply, clutching my letter home and wondering about the battle for Hill 110. Only five hundred meters high, the small hillock or mountain was nearly conical with no good approach to taking it, except by direct frontal attack after an artillery and or air attack. Machines guns, which the NVA had plenty of, made frontal attacks in modern combat about as attractive as a fur covered apple.

I thought about the earlier meeting. It had been a high threat meeting without there being any threat issued directly. I could not meet the threat directly and I could not shrink away from it. So I’d gone sideways. But I had to respond or I would become prey, which I was a bit already anyway.

Chicken Man blasted out from Stevens’ shoulder-mounted radio.

“Benton Harbor,” Fusner said, in obvious surprise. “That’s the secret name of Chicken Man. That’s why you asked Sugar Daddy about that place?”

“It’s a place, too,” Stevens answered. “In Michigan. There was a big anti-war riot there a couple of years ago.”

“Stevens, go on over to where that guy’s platoon is and bring back some bearings,” I ordered “It’s almost light. Should be easy. Pace off the distance there and back.”

“If I go over there, sir, and you drop some artillery on them, then every time I show my face in the Company they’ll think I’m getting their location for you.”

“You’ve taken my order wrong, Stevens,” I replied calmly. “It’s good to know where your people are if you’re company commander. That’s it. So, don’t go. Send our Kit Carson Scout. Why do I have the feeling that he’ll have no problem at all registering where that shadow of a real Marine platoon is set up?”

Stevens spoke softly to Nguyen. The small Montagnard seemed to disappear after the conversation.

“Where are those guys in First Platoon from?” I asked the remaining two members of my makeshift team.

“What do you mean?” Fusner asked back.

“Please tell me that those guys aren’t a bunch of crackers from the South.” I’d heard the talking through the bushes the night before. The accents had all been Southern. If the blacks had all pulled together into one platoon and the white southerner Marines were in another platoon, then the war going on inside the Company might be explained.

“What part of the country?” I said.

“Oklahoma, Texas, places like that, mostly,” Fusner answered hesitantly.

Some things were becoming clear to me, not that knowing what was actually going on would do much to forestall my death. Two sets of officers before me had totally failed, and they must have had a pretty good idea before they bought it, or so I thought until I saw the Gunny coming back.

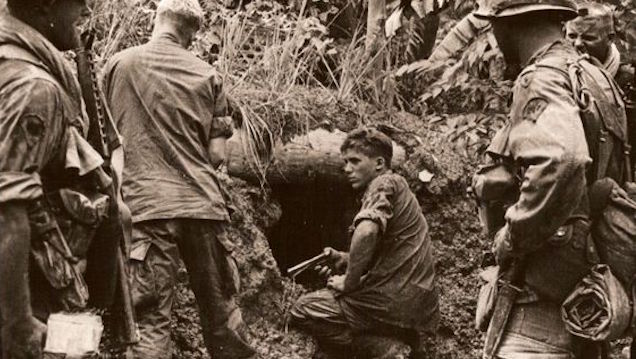

The light was just enough of a glimmer for me to be able to spot him easing from the nearby jungle growth. Five other Marines, all in different states of uniform repair or disrepair, followed him. Some wore utility blouses, some not. Some helmets, some not. I guessed the first man behind the Gunny to be Jurgens. Big and hard-boned looking, he lunged forward more than he walked. The other three, all Caucasians, were nondescript. And then there was Sugar Daddy, who hung back until everyone else gathered before my hooch. I watched them approach, having no idea how the planning for the assault would go. I was mentally prepared with as much training material as the Corps had provided me back in Quantico. The five paragraph order was standard fare for planning an assault. SMEAC was the memory aid acronym: situation, mission, execution, administration/logistics, and command/communications. It was simple stuff but every area had to be covered before more complex acronyms could be brought into play. My right hand remained inside my pocket clutching the letter to my wife, the most important part of my day. My link to home. I wondered if the same Hollywood Tommy gun guy would be there at the resupply chopper to accept it from me. I also wondered, if the rear area was run anything like what I’d discovered in the field, whether my letters would ever reach the continental United States at all.

The other Marines, who I presumed to be sergeants, squatted in the mud facing the Gunny, sideways to me. I got the message. I also wondered where the Company paperwork was stored and moved. Even in the field a clerk is assigned to keep the records, write letters regarding casualties and keep track of supplies and personnel. Where was that clerk and where were the records? I took out a small square of plastic and wrote the number “1” on it, and looked up at the men gathered before me.

“We’re not attacking,” the Gunny stated, shaking his head. The other Marines all nodded their heads. “If we were attacking, we’d just do it without all the mumbo jumbo you learned in Quantico.”

I looked the Gunny straight in the eyes. It was the first time I sensed true resentment in anything he’d said to me. I could not afford to lose the Gunny. He was really all I had. I put my plastic sheet and grease pencil back in my pack as I thought furiously about the situation. We were ordered by Battalion to attack Hill 110. We were going to disobey a direct order in combat, if they had their way, an order I was responsible for obeying. The penalty for such disobedience was clear, and it included punishment up to my execution. I waited. It took about half a minute for the Gunny to go on.

“If we take that hill or even try it, then we’re going to get the same medicine the last outfit got and they lost about a quarter of their men.” The Gunny stopped to let that message sink in before continuing. “Nobody back there gives a damn about that hill or what might be on it. They’re just moving us around. So we sit here, call in some fire and probably take some, but go nowhere. You call Battalion and let them know we took the hill by late in the day. Then we wait.”

“For what?” I asked, giving no indication about whether I approved of the treasonous plan or not.

“Until they order us to move out and on to another position.”

“What happens when we don’t have any casualties or need resupply on top of the hill, or even gunship support?” I asked, wondering how many times this same scene had played out with this group of Marines.

“They won’t care,” the Gunny replied. “We’ll tell them we took the hill unopposed.”

“And if the other companies on our flanks run into the NVA occupying that hill?” I inquired, rummaging behind me for my canteen holder.

“That’s their problem, Junior,” Jurgens answered, his tone acidic.

I noted that none of the Marines attending the meeting appeared to be armed. Although it was almost dawn and we were seldom hit during daylight hours, I still thought it unusual that anyone in a combat situation would go anywhere at all, including inside our own perimeter, without a weapon.

Making like I was going to tear another packet of instant coffee open with both hands, I let my right drop to my side and remove my Colt from it’s holster.

I brought the automatic up and pointed it slightly downward at the space right in front of and between the men. The men froze in their positions, not appearing to blink or breathe.

I moved the safety lever on the back left side of the weapon down. The click of it disengaging sounded like a gunshot in the silence. I looked around at every member of the group, each of whom stared back at me without expression or movement.

“You guys shouldn’t move about in the field without being armed,” I said, not moving the Colt from where I held it. “Always keep one in the chamber with the hammer back and the safety on,” I went on.

Nguyen came silently out of the jungle behind the group. He blended in so well with the foliage I was reminded of an American Indian in the old west. He held an M16 before him, slightly angled down, but its intent was plain. I wasn’t alone in whatever might happen. My heart and intense loyalty went out to him across the short distance.

“Okay,” I said. “We’ll play this one your way. You’re dismissed.”

The Gunny stayed while the rest slowly backed off and then were gone. “You can’t beat them all, sir,” the Gunny said.

I re-engaged the safety on the .45 and returned it to my holster. “Coffee?” I asked, hoping he’d say no because my hands were shaking too hard to make any. I pushed them down into my thighs so he wouldn’t notice. If I smiled any more I’d have smiled on the inside. The Gunny called me ‘sir’ for only the second time since I’d met him. It was a tiny little thing but it was all I had to hold on to.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

Liked the idea of the Fourty five, nice psychology!! As the M60 gunner I also carried one.

We had a possible issue of some guys wanting to beat and rape a young girl we thought may have been VC. My 45 put a stop to all the BS.

The .45 was a true companion and worked every damned time.

No rusted shut cartridge door shit. No jammed rounds in the chamber stuff.

Just there and bang.

Thanks for your support Dave.

Semper fi,

Jim

The command in the rear didn’t care about what it was really like in the field. I used to imagine the battalion commander sitting at his desk with his feet propped having a whiskey and cigar throwing a dart with our company’s name on it. Wherever it landed on the wall map, he would send our company even across our sisters area instead of everyone sliding laterally. It made no sense at times. It wasn’t enemy in front of us and secured friendly behind us. I’m sure you may have experienced going into the same area months later hitting the shit all over again. Your story is riveting and I don’t want to put it down. I put my stepson on to your story’ so he would know what it was like.. He is serving a infantry line company like we did. He has one tour in Afghanistan under his belt and who knows, may have to go again.

A co, 1/327, 101st 68-69

Thanks for commenting Paul. The battalion commanders in my area were in the field but always

way back in reserved behind the companies assigned to do the fighting. The battalion CP was always

staffed by quite a few officers and enlisted assistants. I don’t to this day what any of them did

except avoid going where we had to go.

Semper fi,

Jim

Meant to say enjoying the read, you are certainly good with words, I went over Sep of 69. Was not there to long 30 days two clicks south of DMZ for most of my time there.

I was not a Marine duty I was Army infantry instant NCO and but in the 101 and I was a strait leg, for sure some anomosity arround mt.

Don, really appreciate the interest and comments, and your own service, of course.

Takes one to know one kind of a thing. I will keep plugging away with the exploits of

Chicken Man, as I came to see myself living in that horror.

Semper fi,

Jim

Looking forward to the whole book….sometimes I guess it seems like we all had a bad tour….

Steve, my good friend Chuck Bartok is going to assemble all the days and parts of this odyssey into a book, mostly for the guys who served.

When I’m done writing the segments then we’ll make the book available on this website and also Amazon, although how to do it there is

a mystery right now.

Thanks for asking and being one of us.

Semper fi,

JIM

James,

I didn’t serve, but I must tell you that I have really enjoyed reading your story (on day 4 now). Graduating from college in 68, I had to go into the service (1-A). I remember being concerned with the stories of how the army had deteriorated (drugs, etc.) and that played a big part in my joining the Marine Corps. I did not know this was going on in the Corps. I now consider myself lucky that I was discharged out of Paris Island and didn’t go to PLC in Quantico. I write this to tell you not to restrict your readers to those who served. I have thoroughly enjoyed your writing. You have opened my eyes.

Thanks Rick, and I’m not at all certain that what happened to me was universal to the time or combat itself. The racial stuff was going on all over though,

in different forms. I experienced it some more when I got back stateside. The Marine Corps remains a great background in my life, no matter what.

I don’t restrict the readership, it’s just who comes and I don’t really have the assets to publish myself or the story all over the place.

Thanks for your very cogent and illumination comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

That was some great writing. Quite descriptive. Evoked memories of the little things that I haven’t thought of in years. Thanks. Semper Fi, Brother.

Thanks Jim, for your comment. I know how hard it is to comment on this stuff at all.

I will keep plugging away to deliver the rest of the story….and how i made it.

Semper fi,

Jim

i need to get a copy of this book , not only to read myself , but for my son to read. I was a lowly combat engineer put in some strange situations , but nothing like this at all. We all knew about derelict units , fraggings and people out and out refusing to do their jobs , but i have never talked with any fellow veterans who mentioned anything at all like what you went through.

Chuck, I will make it into a book because my friend Chuck Bartok has agreed to put the whole thing together.

I will not charge veterans for a copy. We are going to work on that very soon. Meanwhile I have to continue to

get it all down. Thanks for your interest add your own service, of course.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great story, Jim. Welcome Home, Brother.

Thank, Kerry. More to come

hmmmm…….Sometimes you have to… “hold your own”, no matter how afraid you are. It seems like you made The Right Call, on This One. Definitely, something to Think about….One Never knows at The Time, but when it is over, and you are shaking so much you cannot even make a cup of coffee, you probably rethink it… over and over and over. So Glad you finally wrote it all down.. Maybe someday, you will find Peace. Thanks Again James for Your Service…….You had quite a Run….Glad you are Still Running !

I think Jim Webb, a company commander on my flank said it best one day. “Jim you’re having a bad tour”, like it was a guided tour for a tourist

or something.

Yes, I had a bad tour…

Semper fi,

Jim