The radio music transmissions were supposed to stop at night but it was not full dark when my small team of scouts and radio operator went to work setting up shelter halves around them. I was afraid of the radio transmissions giving our position away. I smelled heavy cigarette smoke wafting in the slow-moving air around me. The air felt like cobwebs passing over my face, as it was so full of heated moisture. I folded my Iwo Jima flag-raising envelope in half and stuck it into my right front thigh pocket. No matter what happened in the night I was determined to make sure that I sent the letter off aboard the resupply chopper supposedly coming in the following morning.

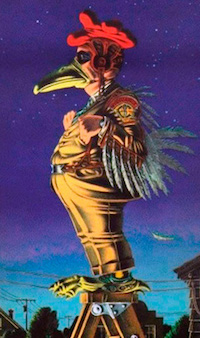

Stevens had a small transistor radio playing the Armed Forces Radio Station. “Ninety-Nine Point Nine FM,” the announcer said in a tinny voice, followed by one of Brother John’s short baritone comments: “Here’s Chicken Man.” There was a pause in the transmission. I wanted so badly to order Stevens to turn the damned radio off but I was afraid to order anyone to do anything. And I was afraid of the feeling it gave me to be afraid of doing that.

“Chicken man?” I asked, quietly, instead.

“You’ll love this sir,” Fusner said, finally easing the big rectangle of the combat radio from his back.

A hideous laugh came from Stevens’ little radio, and then another announcer, obviously pre-recorded said: “Chicken Man. Benton Harbor, salesman by day, and the world’s greatest crime fighter by night, makes his appearance.”

I couldn’t believe my ears. Chicken Man? The announcer went on to describe how Benton had decided to be a crime fighter and gone to a costume store for a disguise. The store only had a rabbit, a teddy bear and a chicken costume available. Benton tried the rabbit suit on and went outside the store, only to be encountered by a passing citizen. The man kissed him, telling him he was a cute rabbit. Benton went back into the store, took off the rabbit outfit, passed over the teddy bear and decided on the chicken suit. Chicken Man was born.

disguise. The store only had a rabbit, a teddy bear and a chicken costume available. Benton tried the rabbit suit on and went outside the store, only to be encountered by a passing citizen. The man kissed him, telling him he was a cute rabbit. Benton went back into the store, took off the rabbit outfit, passed over the teddy bear and decided on the chicken suit. Chicken Man was born.

I looked at Stevens and Fusner. It was obvious they loved the story and the weirdly and totally out of place character. I presumed the story was funny but somewhere in the last two days and one night I’d lost my sense of humor. I reflected briefly, while Chicken Man fought crime over the radio, about how a person could possibly lose a sense of humor while knowing he’d lost it.

The mosquitoes were back. Armed Forces Radio finally shut down for the night, thankfully. I dug my mosquito repellent out of a pack pocket and slathered it on my arms. Stevens passed me a full pack of unfiltered Camel cigarettes, but I shook my head.

“No, for the mosquitoes,” Stevens said, holding the pack out. “You can’t put that shit on your face or it’ll sting your eyes real bad. Light a cigarette and let if burn under your chin. Does the trick. They send us plenty of cigarettes every morning so you’ll never run out. At least a box each.”

“Who sends them?” I asked, taking the cigarette pack while Fusner rummaged in his own pack for a lighter.

“Gift packs from home,” Stevens replied. “They come with notes inside them from people back home. You never know the people sending them and the notes can say anything. We read them every night we get a chance. Really neat stuff some of the people back home put down.”

“Matches don’t work in this place,” Fusner said, holding out a chrome-plated Zippo lighter.

“Thank you,” I said, looking the Lance Corporal in the eyes to communicate my sincerity.

“Oh, that’s okay,” he answered. “We get a ton of them left over from the dead guys every day.”

I stared at the Zippo. Somebody had carved “M.C.” carefully into its lower body. I wondered if it was initials or the abbreviation for Marine Corps. “We can’t take stuff from the dead,” I said, still holding the lighter gently in one hand. “Their stuff has to be bagged tagged and returned home with them,” I finished.

“Nah, not here,” Stevens said. “Not now. Never seen it. The only stuff that goes home is what you take if you live and what you keep from the body of anyone you kill.”

I opened the pack of Camels while I thought. The pack squished in my fingers from the oil content used as the base in the repellent. Would I ever be clean again, I wondered, as I pulled a white tube out, fumbled with it until I got one end in my mouth and the Zippo flipped open. I flicked the small wheel down with my thumb and the lighter flared.

“If you kill somebody you get their stuff?” I asked, lighting the cigarette carefully before pulling it out to hold it under my chin.

“Spoils of war, they call it,” Stevens said, lighting a cigarette of his own.

“Wallets, pictures, notes, insignia, belts, knives and even guns, as long as they’re not full auto, get sent with re-supply. They send the stuff to Division where it’s stored until we go home, and then they ship it.”

I couldn’t believe my ears. Why had I heard nothing of the spoils of war? The whole thing sounded like it was a description of what might have happened in war situations hundreds or even thousands of years ago, not the late sixties in the Marine Corps. I had no reason to disbelieve the boys in front of me. They were a mess I realized. Dirty to the bone, nervous as displaced spiders in little ways and looking to be saved. I could see it beyond the surface deadness in their eyes. Could I save them? Would I be the one? Would I get them out of hell? I had just turned twenty-three. Their looks were like knives going straight into what was left of my heart. I’d been there two days, one night and now moving into a second night and already I knew. I couldn’t save them. I very probably couldn’t save myself.

The Gunny appeared out of nowhere. He knelt on the edge of my poncho, which served as the floor of my half-tent. He took out a canteen and handed it to me.

“Drink that down. Last water until dawn. Pull out your map.”

I opened my left thigh pocket and took out my one to twenty-five thousand grid-photo map. The area it covered was about twenty kilometers by twenty. An Hoa, the fire base for artillery and landing strip for small air support was in the lower left hand corner of the paper. I spread the map out as best I could without dropping the cigarette or losing the lighter. The rubberized surface of the poncho cover felt wet but then everything felt wet.

The Gunny knelt and examined the map.

“Night defensive fires?” he asked, noting the grease pencil numbers all around our current position. I hadn’t registered our exact location with an artillery round but I was pretty certain. The Gunny took out a small pencil flashlight.

“Here,” he said, pointing at the map. “Hill one ten, on this side of the slope heading west into the A Shau Valley. We head on over there tomorrow. Seems like some Army insertion went wrong.” He clicked the light off and pulled some stuff from his pack. He lit a fire after plopping some C-ration cans nearby. “Dinner. Eat if you can. We’ll be moving long and hard tomorrow after resupply and medevac.”

“Medevac?” I asked, my mind going back to the corpsman problem I’d been given earlier to somehow deal with.

“Yeah, they’ll know we’re moving out in the morning so they’ll hit us tonight. Again. I’ll be back.”

I moved over to the small fire. I noticed that there were fires all around me and hushed conversations going on but nobody approached. I’d met none of the Marines, had no opportunity to identify or see the non-commissioned officers leading our five platoons and I hadn’t been consulted about the coming move on the following day. I presumed that Mike Company would be assaulting Hill 110, but there’d been no operational planning meeting I’d had any part of.

“When did he get the orders?” I asked Fusner. “Don’t we get the command net stuff all the time on your radio?”

“Nah, I don’t turn the radio on unless we need to call somebody, sir,” he answered, puffing on his own cigarette. The Gunny has his own radioman. He talks to command as the six.”

For the first time I was more angry than I was afraid. In training I’d only had three hours of schooling on how to use the Prick 25 radio but none at all on how to access different commands or even what the language was. I knew the “six-actual” of the unit was the commanding officer in person. The six referred to someone acting as the commanding officer or for him.

“Turn it on,” I ordered. “I want it on all the time. Scroll between the command net and artillery all the time I want to know what’s going on and what the Gunny’s talking to command about.”

“He may not like that,” Stevens said.

Fusner handed me a tiny little folding can opener. I opened it and began working slowly around the edges of a can the Gunny had left behind. I had to eat but I wasn’t hungry. I needed sleep but I wasn’t tired. The Gunny’s words “so they’ll hit us tonight” reverberated through my brain. It would be my first contact if it happened. I didn’t count the horrid weirdness of the night before. That had simply been a confused mess of nightmare oddity. The day’s hike had been strange, with little regard for security. We’d taken the high ground all the way without regard to a surrounding enemy. The radios had played and all the Marines had been talking to one another, like we were in training. The night was filled with small fires and hung over with a pall of cigarette smoke to fight off the mosquitoes. There was no hiding the two hundred and seventeen Marines plopped down atop the only high ground around with machine gun snouts sticking out of the brush everywhere.

Hit? Of course we’d be hit, I thought darkly, leaning back into my half a tent, mist starting to fall on the shiny edge of my poncho cover. I ate ham slices that tasted like dull old spam. I drank down the liquid after, as I had the water in the Gunny’s canteen. Water was everywhere but in short supply for drinking.

I didn’t sleep. I laid down, my face only inches from the shelter half canvas, listening intently for the enemy through the slight rustle made by water drops running down the outside when enough mist had been collected together to drive them.

We got hit at 2:07 a.m. exactly, according to my combat watch. It started with light machine gun fire going outward from our perimeter I guessed. The sound of the M60s was distinctive, a smooth sort of cracking sound, the bullets going out distinctively from the guns, not like in training. There they’d seemed jarring and staccato in their desire to get out of the barrel in a mass and move downrange. The firing spread all around me, going out into the night. I hugged the poncho cover, rolling onto my face. I had my .45 Colt strapped to my waist but it seemed idiotic to take it out. There were real guns going off all around me.

I didn’t look at my watch again. The fire escalated and got much louder. I knew we were taking fire inside the perimeter because tracer bullets began curving over my shelter half. Far enough away to make me shiver but not make me quiver in terror. That started with the explosions. The north side of the perimeter erupted in a series of large explosions.

“Fucking Chi-Com grenades,” Fusner shouted, from somewhere nearby. A bigger gun than all the rest opened up and I became terrified. The bigger gun was even slower in delivering its automatic fire but the size of its tracers made them look like express flaming beer barrels going over. It was enemy fire and had to be the 12.6 mm heavy machine gun the enemy used instead of our own Browning .50 caliber. We didn’t have a Browning in the company. They were simply too big and heavy for a ground unit to carry.

What broke me was when the beer barrel trajectories dropped until they were coming in only a few feet over my head. I went blind with their glare and the sound was causing me to lose my hearing when I ran. I’d looked up and out through the bracken to see where the tracers were starting from and it was close. It seemed that they were inside the perimeter. And it was enough. It was too much. I moved rapidly, running fast and staying low. I ran directly toward the paddy dike we’d come in on. And I didn’t make it. Just before breaking free of the heavy growth a huge force closed around me and drove me into the mud. When I hit the weight just increased until I was almost submerged in the squishy mess of the paddy dike wall.

“You stay,” a voice yelled into my deafened right ear. “You stay until I come back for you. You’re the company commander, you don’t get to run away.”

I knew it was the Gunny’s voice but it took me seconds after his leaving for my mind to work well enough to figure it out. The firing continued but more in the distance. Apparently we weren’t surrounded. It hadn’t occurred to me in my full panic mode to consider that I might be trying to run through my unit’s own machine gun fire at the perimeter or why there wouldn’t be enemy attackers where I was trying to go.

I waited. I breathed slowly, feeling the mud and muck begin to congeal around me. I was half buried in the stuff but I didn’t move. I had nothing. I had no courage, no honor, no nothing. All I had was the Gunny and he’d said wait. I counted breaths. Sixteen to a minute I’d heard somewhere. I did sixteen one thousand times. I was just over three thousand sixteen breath bits when the shooting stopped. Things went quiet, except for some mute screaming in the far distance. I started counting from the beginning but didn’t get far. A big hand reached down, grabbed my arm and eased me gently upward and out of the grip of the mud. The Gunny let go. I sat there, the first light of dawn just barely beginning to make itself felt.

The Gunny smoked a cigarette, squatting like a gook not very far away.

“Your first contact,” he said, between slow puffs.

“Yeah,” I agreed, shakily, trying to pry loose some of the mud clots that had dried to my clothing.

“This is my third war” the Gunny said, facing toward where the sun would eventually come up. “It’s the worst one of all.”

I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t want to say anything. I didn’t want to be there. I didn’t want to really be anywhere anymore.

“You think you’re a coward,” the Gunny said with a faint smile on his features, barely visible in the low light. “You think you ran under fire. You think that proves something because of what you’ve been taught. Well, there’s no teaching for this shit. If you tell people later on what it was like they’ll think you’re nothing but a liar.”

I listened intently, trying to grasp what the man was saying, but not quite getting it.

“You’re just a kid. You ran because you’re an intelligent kid. I was there behind you because I’ve been in three wars. I knew you’d run. The good ones always run if they have a brain. But you won’t have to run again. Next contact you’ll stay but you won’t be able to say or do anything. Maybe after your fifth contact, or so, you’ll be able to talk. Nobody will listen to you. It’ll take a few more before that happens, and then you’ll be okay. I mean if we get that far. The last part I can’t help you with. If you stay here too long and go through too much of this, then you’ll get to look forward to the contacts. You won’t come back from that and I can’t help you with it if it happens. Let’s go. Everyone knows you’re here, what happened, and nobody gives a shit. We’d all run if there was somewhere to run to.”

The Gunny slowly got up and stretched, field stripping his cigarette and fluttering away its small remaining bits. He walked back into the bush we’d come out of.

When I got back to our small CP area my stuff was all packed up and waiting. Fusner, Stevens and Nguyen made believe I’d never been gone. There was no time to say anything because the sound of a helicopter approaching began to dominate the whole area. The resupply was coming in. I knew from the deep dissonant roar that it was one of the big dual rotor jobs that could haul a lot of stuff. I heard a second machine in the distance.

“The Huey’s resupply, if you want to mail your letter home, sir,” Fusner said through cupped hands. “The big one’s for medevac. We lost a few more than usual. The Gunny’s bagging them up and filing the tags.”

I looked around but saw no special activity anywhere. In the jungle all sorts of stuff went on only a few feet away that you might never know was happening unless you stepped right into it. The jungle seemed to have a life all of its own. I looked back at my small team and then made my way to the open area near the paddy dikes where I’d spent the night. I headed for the resupply chopper and got my letter off to my wife, or at least placed into the hands of a crewman who looked like he was from a war movie. He stood next to the chopper with his legs spread, the finest new jungle utilities on, and wearing some kind of cowboy cavalry hat folded up on one side in the Australian style. In his hands he balanced a Thompson submachine gun. He looked so wildly out of place in his Hollywood outfit and back home cleanliness I would have laughed at any other time in my life. He took my letter with a grim expression, playing his role to the hilt. I walked away, back toward my team.

As I walked I looked down and saw the imprint my body had left in the mud the night before. I smiled to myself with a twisted bitterness.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

You did great. I’m a youngster (served 88-92). I was born about 10 months after my dad got back from Nam. He was an army Medic. The only thing I really have detailing his service since he didn’t talk much:

http://i198.photobucket.com/albums/aa160/bobbyminchew/dadarticle_zpsa234ee53.jpg

http://uploads.tapatalk-cdn.com/20161111/e512ec4cb8f54c3399ec507b2ed83140.jpg

Thank you ever so much Bobby. I am trying my best to churn it all out. Medics and Corpsmen were and remain special people.

Essentially unarmed they came when called, even through the worst of fire. Beloved men in almost every unit. Thanks for adding

those things to the site here and your genuine comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

I swear the guy with the map & the mustache above is then SSG Wayne P. Freebersyser. He served with the 1st Air Cav, 196th burning rope & Americal as a platoon leader. He was gut shot in 69 & medivaced He was my 1st SGT in the 63rd EOD from 71-72. He left EOD (Explosive Ordnance Disposal)in 65 or 66 to go back to his primary…11B. He was that kind. Drunken, violent, promiscuous, but one of the finest NCOs in anyones Army when it came to mission or the troops. After a bad mission where I & another FNG showed we could & would follow dangerous orders he took us under his wing. I realize now he had deep PTSD & another person in the unit later confirmed it. Smart crazy SFC. I wish I could post a picture of him from 72, you would know it is the same guy.

Thanks for your comment, Tom.

The images we have been using for the story are taken from Internet, (Pinterest) mostly.

We have no information images or personnel

Great account of hell on earth. Semper Fi. Lima 3/5. 0341.

It sure as hell was not heaven. Maybe a form of purgatory, although I don’t think I sinned

that much when I was younger. I sure worked those sins off, only to commit some rather more violent ones

while in purgatory! Thanks for he comment and the reading.

Semper fi,

Jim

Brings back so many memories and fears that were hard to accept. Gunny was right in that the unknown becomes the

reality you expect. 1st Eng. Battalion been to An Hoa. Great writing. Please continue Lt. Semper Fi 69 – 70

Thank you Gary. Quite unexpectedly, I have received a lot of comments

like your own. So many of the guys discuss the fact that all of us remember so

many of these things so vividly but go through life kind of avoiding triggers that might

take you back or somehow upset the apple cart about making it home. I’m putting it all down

more for posterity (and why is that important I’m not at all sure) before I get to a point where I

can’t anymore. I didn’t think so many veterans would be so open about wanting to hear it. So

I will continue.

Thank you most sincerely,

Semper fi,

Jim

I found this segment to be So Real, from what I have heard from Others. I am glad you are getting it all down in writing for Others to read. It is Important…. It is Valuable, and enlightening… Many feel ashamed, and humiliated, and scared of what People will think. People have No Idea, what Being Scared is really like. Being scared, and trying to save yourself, so you can save others, when you have No experience… Tough Times For Sure… I appreciate, all that You have given and taken… It was a HELL of a run !!!

Indeed!!!!

love,

jim

Well written, Jim. I appreciated the honesty… and your Gunny’s advice. I spent a year in Nam with with 1st Cav (1970) as a Chemical officer at Div. HQ, so I never experienced the horrors of combat that you did. My Dad, a WWII marine NCO, told a similar story about getting terrified men to move out of a mortar kill zone on Bougainville… His only advice before I left was, “Find a good NCO and listen to him.” Semper fi.

Thanks for the supporting words Mike. This is a hard one to lay down

and write about because it is so damned sensitive for me and others who

read it. Some don’t agree at all that any of this could really have

happened the way I am writing it. I do not know if the critics were those guys int he rear

with the gear or not, or were even in the zone. Anyway, thanks for what you did and

your dad too!!!

Great work , Welcome home Semper Fi and God Bless Sir/Brother .

Thanks Jeff…….

Even though many of us have “been home” for 45+ years, some things seem to linger

Hey, Jeff. Thanks for the welcome. I’m not at all sure its possible to

‘come home’ simply because it’s not the same place you come back to after that.

I mean it really is, but you don’t come back being able to see it the same

way anymore, and that was horribly unexpected. My wife literally did not

know me to look at or talk to. That cut me to the quick more than

anything…and showed me that ‘home’ was not the place I’d left.

Appreciate your honesty writing skill .

Thank you Fred, it’s been a long time since all that stuff went down. The return home, even on a gurney, was almost as shocking as the whole

war thing. I just could not recognize the same world I’d left not so long ago. I could not accept that the world was the same but that I

had so changed. Take care, and thanks for reading and commenting….

Semper fi,

Jim

Just found your post on Facebook tonight. Enjoyed reading the first one. Will look at the rest I have missed. 11th Armored Cav., 68. I also am in my 7th decade. Keep them coming.

Larry. I much appreciate your comments, especially coming from someone who served with the Black Horse at the same time! I am laying it all out for whatever the hell its worth, which is something to those of us who went I hope. I saw Platoon and thought it was kind of a big close, but not nearly dirty, stinky or rotten enough to portray my war…and your war. Thanks again for reading and, in your own words, finding me okay!

Allons

Jim

Got to have been there with in-coming to understand it – ain’t too sure I like going back there.

My brother was an Army Ranger Jim. Unfortunately, he didn’t make it. They never told us we didn’t have to be in combat at the same time. Life.

He got it down at Bien Hoa while I was up at An Hoa. It’s not a comfortable story, you are right but I thought it was important to get it all down, finally, after all these years. I share you pain while I write.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great stuff

Appreciate the compliment, William.

Always feel free to share your experiences on this site.

It is my desire to let coming generation know the reality and not the false images portrayed

though film and other media.

There is nothing nice about situations like this.

Nice piece, kept me in until the end !

Appreciate that Kirk.

Have you signed up for the updates?

Keep it coming brother.

It was short lived…….

but more is coming. Thanks for your support Jon