Booby traps that weren’t made with detonators or explosives subject to sympathetic detonation couldn’t be destroyed, disabled or damaged by the rolling artillery barrage I’d designed, and that the battery had applied so effectively. The machine gun had caused significant casualties before the artillery had blown it and its emplacement to hell. And now three lowly punji pits, along with one sniper, had brought the company to a dead stop. Punji pits were made by digging a shallow hole and then inserting sharpened up-pointing sticks into the mud at the bottom of the little pits. The sharpened sticks layered in human feces, and generally barbed as well, penetrated the bottom of any Marine’s boot unfortunate enough to plunge through the disguised hole covering. I’d heard rumors that the newest issue of jungle boots had a triangular aluminum bar built into the soles that made them punji pit proof, but nobody had seen or been issued such a set in the company.

The Gunny called me up to the point in order to attempt to deal with the sniper. The company came to a halt as the sun set. The evening mist and the lugging of casualties, along with packs and the other equipment necessary to operate a reinforced Marine company, had already slowed our progress to a snail’s pace before the sniper showed up and stopped it completely. As I moved forward the going became more difficult. Walking became climbing and the mist on the forest floor made the strewn plant life and blown-apart wood pieces as slippery as the mud. I labored toward the point, with Fusner cursing behind me as he carried the twenty-pound radio with extra batteries. It didn’t take a genius to figure out that the company itself would never make the ridge before dark. The Marines I climbed around to get to the point were all digging in and setting up for a night that had not come yet.

I finally arrived near where the Gunny lay talking on the radio, Pilson not far away with his Prick 25. Each platoon had small radios called sixes leftover from the Korean War. Most didn’t work at all unless the operators could see one another. They looked like giant bent bananas, green in color. A Marine with one of the six radios talked on it. I presumed him to be the acting platoon commander, probably talking to one of the other platoons over the limited range radio.

A shot rang out from somewhere in front of us and everyone ducked down, even though anyone I could see already squatted, or lay under or behind, some sort of cover.

“Anybody hit?” the Gunny yelled.

No answer. I reached for the artillery net handset and Fusner complied instantly. I really appreciated his ability to sense my needs from a single gesture.

“Fire mission, over,” I sent.

“A lotta good artillery’s going to do when you can’t see shit,” the guy with the six radio said.

“This sniper hitting anything?” I asked, surprised by the sniper’s last shot being placed to hit no one in particular.

“He’s a lousy shot,” the Gunny replied. “Hasn’t hit shit but we can’t move past him until we take him out. They’re probably stalling us so they can set up an ambush ahead. Can’t flank him successfully because of the size of the clearing in front of us. If we’d taken Hill 110…” his voice trailed off.

“In contact, one round Whiskey Papa,” I said into the handset, and then read off my second to last zone fire coordinate key, with code from memory.

“Your position?” Russ asked, his voice coming over the little speaker built into the top of the Prick 25.

I hastily calculated where we were likely to be, and although the body of the company lay strewn behind me for nearly a thousand meters, the battery only ever asked for one grid coordinate. The FDC would approximate ‘check fire’ radius using its own numbers and approximations. I could have taken a bearing on Hill 110, visible on our left flank across the valley, but after my run through fire, however inadvertent it had been, I was in a wild guessing mood. I gave the battery a number and seconds later the Willy Peter lit up over the top of the path about a thousand meters in front of us.

“Told you,” the six radio man said, as the sniper fired another round into the jungle bracken somewhere nearby.

I motioned for Stevens to come, as the scout team had followed me in my move forward.

“Watch the trees up ahead,” I said. “We have visibility for about a thousand meters. The sniper’s using an AK that’s well beyond its effective range, and he’s probably using metal sights. Spot the muzzle flash when he fires again.”

“But when’s he going to fire?” Stevens asked.

“The muzzle velocity of his rifle should be about six to seven hundred meters a second,” I said. “He’s such a shitty shot because he’s using shitty equipment. If I walk slowly and turn then he’s got to figure out where I’m going to be a second and a half or so before I get there. Watch the tree line.”

I stood up, handing the handset back to Fusner, and walked forward toward a thick-trunked tree. I abruptly stopped, turned and then went back the other way. A bullet seemed to whisper past the back of my head, the sound of the shot coming out of the barrel arriving a few seconds later. I dropped to the jungle floor.

“You hit?” Fusner yelled.

“You get his position?” I asked back.

“Yeah,” Stevens said. “He’s about two fingers to the left of the smoke from that last shell and maybe a bit forward.”

I grabbed the radio handset and called it in, dropping fifty meters and shifting the fire of the spotting round two hundred meters left, figuring that a finger held up translated to about a hundred meters at a distance of a thousand. I called in a battery of six.

After the ‘shot, over’ came through the speaker, I yelled for everyone to get down. “These are going to hit hard and close!” I covered my ears with both hands.

The battery of six came in, wave after deadly wave, the nearer rounds impacting, by less than five hundred meters, the relatively open area between our position and the forward tree line where the sniper lay. Peeking over the edge of the fallen tree after the ‘splash’ transmission, I saw the white blossom of a shock wave rushing outward and at me. I scrunched down to take the shock, but too late. The blast threw me a good ten feet backwards. Nobody moved to help me as the other six round impacts came down in waves with only seconds between them.

“You all right, sir?,” a voice I knew had to be Fusner’s said from a distance. Only Fusner called me sir.

I’d dropped my hands when the last of the rounds impacted.

“No more sniper,” the Gunny said, “and you are battier than bat shit,” he finished. “You never ever stand in front of a sniper,” he continued. “Not ever.”

“He wasn’t a sniper,” I defended. “He was just the delaying action. We can move now.”

In spite of holding my hands over my ears, they still rang, and my head felt like a big giant marshmallow from the shock wave of the round I’d been stupid enough to stick my head up to see. But I knew that I’d never ever forget what the white rolling shock wave looked like as it crushed the water out of the air in its passage.

“White water,” I said, a bit giddy to be alive. “It’s white water, like in the waves.”

“Water, give him some water,” the Gunny ordered, pointing at Zippo.

I lay on my back, not wanting any water but figuring it was better that they thought I needed some than for them to really understand what I wanted to say. My mind would not come back from Sandy Beach on Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands. I wondered, if I made it home and back to that particular beach, whether I’d ever swim there and not see the white rushing aura of that artillery round’s expanding halo.

The man with the six radio walked by my prone figure, glancing down as he passed.

“You one crazy motherfucking dude, Junior…but you’re our crazy motherfucking dude.”

I wasn’t sure whether what he said was a compliment or an insult, or an insult inside a compliment. I sat up. No incoming that I could hear. The Gunny squatted down beside me to make coffee. I moved to join him, although I didn’t have my pack. I knew Zippo or Stevens must have it somewhere but I wasn’t going to ask.

“We can move forward,” I said, the Gunny sensing my predicament with the coffee and handing me a spare envelope.

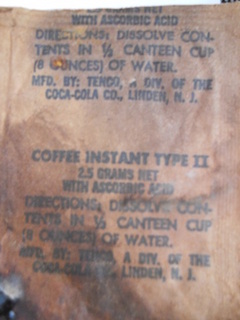

I heated my water, sharing the burning explosive with the Gunny. I read the coffee envelope. Made by the Coca Cola Company,  which seemed strange. Then the Gunny came up with a package of sugar. I didn’t know if California produced sugar but if I ever got home, I determined to support Dole, the only sugar producer left in Hawaii.

which seemed strange. Then the Gunny came up with a package of sugar. I didn’t know if California produced sugar but if I ever got home, I determined to support Dole, the only sugar producer left in Hawaii.

“We’re setting in,” the Gunny said, confirming my previous thoughts about the Marines digging in further down the path. “The open area out here can serve as a landing zone in the morning. Find a place a bit back down from here. The perimeter will run along the edge of this clearing and First Platoon will be on watch. They may attack across there tonight because they’ve had long enough and besides, the A Shau Valley is Indian country.”

I mixed the coffee and sugar and then drank the result, which seemed too wonderful to be what it was. I emptied the canteen holder and replaced it on my belt. Having my canteen full of water made me happy, too, although I realized that I was experiencing some kind of high from almost being dead but still alive and relatively unhurt.

When I was done I got up and moved down the path. I had no good reason to be alive. None of the danger I’d been in since I arrived lessened one bit, but I could not keep a certain bounce from my step.

My team struggled to keep up until I stopped about a hundred and fifty meters back the way we’d come. A small hill not far from the main course of travel looked like a perfect place to set up the Starlight Scope. I worked through wet messy undergrowth to climb to the top, thinking one man could view the small area around us quite easily. The flattened top of the hill would accommodate all five of our hooches.

I wondered who would be coming in the night, this night? The platoon of small-minded country racists or the platoon of angry black combat avoiders who still seemed to fight quite a bit, as long as it was inside the company. The platoon commanders were successful tribal leaders in the company, as was the Gunny. But I was not. I had no real place unless I could find a place, and the only thing I had to offer were my services. Those services had been badly needed, but mostly ignored or underplayed, before my arrival. Would I have enough to offer? Would I have enough to offer in time?

Fusner joined me on the hill, dragging my pack up and turning on his little transistor radio. Brother John came on immediately with his last offering of the day. Some sort of Native American Apache War Chant, he said. “Hena hawaya yo, hen na yo, hey ya hey ya a,” accompanied by beating drums with the same lyrics repeating over and over again. I had no idea what they meant but for the moment, I felt like an Apache sitting on a mountain top of the American Southwest so many years in the past. I thought about moving from the Go Noi Island area, called Arizona Territory by the men around me, and then on up to the A Shau, which they called Indian country. The Apache War Chant seemed most appropriate, indeed, and I wondered how Brother John, down country somewhere in a place called Na Trang, could know that.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

Jim,

I have not read anything until coming across your writing that embodies the soul of Hemingway’s statement; ” There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed”.

Thirty Days is remarkable

Everything written or put to film before it is piecemeal.

You have written a fusion of them all. and then spoke life into it.

Namaste.

Thank you Todd. It is sometimes uplifting and wonderful just to read the words written by men like you. I don’t get

the same thing from my own writing. I’m critical and sometimes lost in the detail of trying to bring it all back. I also

sometimes have a hard go of it deciding about reality. Did it really happen that way or is that part imagination, bad memory

or just the way I wanted or didn’t want it to be. Much appreciate the compliment this morning…

Semper fi,

Jim

James, I trust at some time during your tour you were around the guns when we had a fire mission. With every fire mission came a sense of urgency. We hustled and cranked those rounds out knowing we had grunts lives in our hand. Regret I was not with you, Proud to have been there for you. D-2-11 (105’s)1st Mar Div 1966/67, everywhere between Chu-Li and Da Nang. Semper-Fi.

The guys like you Ben, back at the battery.

You saved so many and the accuracy and dependability compared to calling air was simply without compare.

Trust that those of us in the field thanked our stars every night that you were on our side and

back there waiting to be called.

And sometimes, you guys on the arty net radio were all the counseling any of us got.

I could not talk truth to Russ back at my battery or even Johnson over at the Americal battery but both of them got me through some rough mental patches.

The unspoken unknown part of the war.

Thank you for the great comment, the arty in the Nam and for reading the story.

Semper fi,

Jim

Keep writing.

I love it.

Got my ass blown off a bulldozer on Ga Noi Island summer of ’70 knocking down bamboo and filling in bomb craters. Never found out what the hell I hit. Booby trap? Perhaps a dud that you had called in before I was there. I had made two passes filling in a bomb crater and the 2nd Lt stopped me with his fist in the air and started climbing up. I reminded him that the 1st Lt had stated no more riding on the tractors after an operator and a combat engineer had been medivaced for burst eardrums and Batman, shit you not, real name, had been medivaced when he lost the tip of his right middle finger both after hitting whatever they hit earlier that morning. I finished backing up and started forward and went boom.

Love your writing.

Following another story about Que Son Valley.

Not Khe Sahn.

My brother was wounded the same as you although he was on top of an APC.

He was sent to a different hospital in Japan than I was. He came to see me

in Yokosuka when he was ambulatory and on his way home. Unfortunately,

like the C.O. in the MASH television series, his plane crashed on the way home.

Thanks for your reading and the comment. Gallows humor in losing the end of a middle

finger in Vietnam!

Semper fi,

Jim

Heartfelt condolences James for you and your brither’s tragedy.

Double dose of irony getting a lfinal visit and a forever loss.

I didn’t get hurt. Blew me about 25 yards to the left. Knocked all the wind out of me. Stood up trying to get my breath. Heard a god awful grinding, squealing noise. Thought another explosion was coming.

Ripped my flak jacket off and started running. Stopped and turned around after nothing else blew up.

It was the gear box churning away after the track had been blown off, the belly pan pushed up into the crankcase and the engine and transmission still running until it seized.

When I got my breath, the 2nd Lt stumbled up to me and I said “Where the fuck were you? I thought you were dead.” He answered “I saw you running, and I was right behind you.”

I had a scratch on my upper right arm, he had a gash on his chin.

He wanted a Purple Heart. I didn’t.

1st Lt said it was up to me. I smiled. Not gonna embarrass me.

2nd Lt. Never did like me. I told him not to climb up there. He said it was too hot and boring just standing around and got his 30 second ride.

I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry when I read this comment Steve. The weird humor of it all while we were there and the strange

relationships between enlisted and officers. And the depth of ignorance of those of us who were new! I was right behind you lieutenant. That has got to be a tag line I can use and steal for somewhere! You are terrific Steve and my thanks and appreciation go out to you….

Semper fi,

Jim

James, I believe the relationships and therefore respect were based on time in country (experience). Not so much rank and officer enlisted lines at the company level.

I hadn’t been there a week, and the entire company went to Red Beach for a day of beer and ocean.

This is Vietnam? A war?

I’m embarrassed to share this reality with your nightmare.

I only had 8 months to go on a two year enlistment when I got there in May of ’70. The older guys learned that. And by ollder, I mean in country. Mind you, I was 21 by the time I got there. Then I got a combat promotion to Corporal in June. Combat promotion. I hadn’t been in any combat. We got shot at. We got mortars at night. We always had three tanks with us and they loved to shoot back.

Quotas. That’s all that was. They had a quota for an E4 in that MOS in that area and I got it at 16 months in. My peers saw that. Now I was shorter and getting paid more than a few and I saw and felt that.

That all went away as the older guys rotated out.

I believe the 13 month rotation of individuals instead of units in Vietnam did tremendous harm to the vets.

I was home wearing skivies two days after leaving Vietnam.

Wouldn’t give me my flight date until the day before I left.

No different than most of us.

You are exactly correct in every area Steve! But not understanding that going in was a tremendous disadvantage.

I think project transition, where they replaced killed and wounded by helicopter was the worst thing of all.

You didn’t get rotated out to recover and train the replacements.

Combat is one hell of a teaching environment and death

is usually the only tool. Thanks for the wonderful comment and your interest in what happened to me.

Semper fi,

Jim

Recon Plt . 1st / 22 Inf 4th Inf Div The Higlands 69-70 John, you wrote it the way it was. We called in fire from every thing from mortars to close air support . My hat really goes off to the sailors on the Mighty Moe who were on target with 3 rounds of 16 inch HE. A whole mess of Charlie’s had us pinned down and it seemed that no one could come to our 4 man recon team to help us out. We were out of range or they had other fire missions ! There was nothing left after 9000 pounds of HE hits the target !!! Thank you NAVY ! So many thoughts going through my head after reading these posts but the main ones are thanks to the USA for training us so well, being equipped to get the job done, knowing that my brothers had my back and my faith in my Lord Jesus Christ. Plt SGT

Thank you Curtis for you informative comment. Yes, we sure as hell had ordinance over there and I to

got to call in the bit Mo twice, or at least the NFO they sent in to call it for us. He lasted two days.

Those sixteen inches were extreme, as extreme as the B-52 runs but more accurate. Thank you for commenting and

for reading my story. I am doing my best to get it all out while I still can. Writing it brings it back in such

detail that my nights are kinda hard and that makes it difficult on the people around me that I love. But I gotta go on.

I just have to.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, I was with the 196th Infantry Brigade in 66 and 67.We began in Tay Ninh and wound up at Chu Lai. Your story on the Sniper brought memories. My Platoon was pinned down by Sniper one day and an air strike was called in to take him out and some of us were hit because they dropped stuff so close but they got him. Thanks for your story.

Galen. Air was always a problem over there, as I will write about as the story continues.

Air was so damned inaccurate and unavailable when really needed. Also, unlike artillery, it was

so long in coming once it was called. And then the damned Prick 25 could not talk to the planes themselves.

That took a special hand held that didn’t always work because it was so seldom used. Thanks for the comment and thanks

for the reading.

Semper fi,

Jim

Not a Vietnam vet but I am a Iraq/ Afghanistan one. Marine 0311 for 16 years. Your story has me hooked! I can feel the rumbling of the mortars and artillery. Great job!

Thank you for the reading and the comment. Coming from a more modern warrior that’s quite a compliment.

Those terrifying days and night but also it was like being in the center of a great jungle ampitheater with

orchestra’s playing or the the march at the end of the first Star Wars movie. It was awful but it was life at its

deepest and darkest fringe of huge powerful emotion.

Semper fi,

Jim

1st Bde , (separate) 101st ABN 66&67 VN

The jungle itself was a nightmare , especially in a “firefight”. The M16&16A-1 were highly unreliable.

The “over-under ” version was worse .

Stephen. The fixed that damned gun. In 1968 they came out with the new buffer group

and the better ammo. And it worked. The 16 so outperformed the AK it wasn’t even funny.

So sorry you guys had to work the bugs out. Thanks for doing us that favor.

And thanks for coming here, reading my story and taking the time and trouble to say something.

Semper fi,

Jim

As impressive as your writing is, your taking the time and energy to compose a thoughtful reply to all of us here is even more remarkable. You’ve got a lot on your plate. We all appreciate your efforts.

I agree John,

One thing that has been true with James, over these past 40+ years, is his real caring for others.

Never read comments so real and sincere in my life. I can’t not reply

no matter what is on my plate. What a bunch of great men. With John Conway

right up there at the top.

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

“Can’t not reply”. The infamous double negative. OCS Sgt Instructor (name withheld): “Y’all ain’t got no talent at all for marchin’. I’m going to fix that if it’s the last thing I never do.” Yep, he said that. A lot. Try keeping a straight face, Candidate.

My own Platoon Sergeant: “Well, God damn it, you bunch of college weasels, about all you can do is suck a liquid fart!” No negatives there!

Thank you John for the pithy well-written comments.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thank you for your narrative. I never saw Viet Nam! My brother Kevin did. My brother Pat served in Thailand. I was in Libya when JFK was killed.I volunteered for Viet Nan but was told we were still fighting the Russians 2 more years in Germany. Air Force No one of that time can reconcile the valor, courage and horror that transpired in those many years.God Bless you all, my brothers! John

Some of my fellow classmates went somehow to Korea or Europe and not to Vietnam.

There was no way to know who got what MOS or why or where anyone would go, much less end up.

My good friend Steve Pfarr went over with me on the same day to the Nam but went further North

and claimed to have spent a whole tour without ever contacting the enemy. He was 03. I wonder through all

the years whether he was telling me the whole truth or just not able to talk about any of it. Never saw him again.

Thanks for your comments and the reading.

Semper fi,

Jim

Glad you came through without getting hurt. Not having to go was okay!

In 62 my dad asked, “in which branch of the service I was going to volunteer for after graduation in 63?” I chose the navy and I have thanked him ever since. USS Enterprise CVAN-65 Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club 66-67. I often ask VV’s if it was worth the lost of life and national treasure, esp. when today VN is a one of our trading partners. Most have to stop and think real hard before answering. I urge them to read this book: “VIETNAM, THE TEN THOUSAND DAY WAR.” The reader will soon learned about the OSS helping Ho Chi Minh fight the Japanese in 45, and the French using Japanese POW’s to fight the Viet Minh after the world rejected Ho’s attempts to be recognized as the legitimate government. French colonialism sucked the US in to an unnecessary war that only helped the defense contractors.

Thanks for that historical backdrop and for being offshore to support us.

I never found old rumors about inter-service rivalry to be true in the Nam.

We all worked and got along together pretty damned well.

Thanks for commenting and reading.

Semper fi,

Jim

I watched the VHS tape series. I was trying to come to some idea of what had happened to us. Didn’t take me long to figure out that we backed the wrong people!! I love my country, it’s the politicians that suck!

Semper Fi

Too true, Dave, and then the leadership completely misgauged the kind of war it was

going to be. The belief that technology would reign supreme was never surrendered and

it would have won…if we’d stayed at it. But won what? You can’t beat a whole population

and then maintain whatever you won forever. Most of the backbone of he country never came

to understand what the hell democracy was! Our education of the public was awful because

we didn’t know how to reach them. Our own media liked us but didn’t support us back at home

either. When we came home the media started this ‘poor returning veteran’ crap that has prevailed.

Thanks Dave, for your comments and being spot on…

Semper fi,

Jim

James,

I was there later than you, and flew Cobras down in the Delta. We supported several ARVN divisions and USMC around CaMau and NamCan. The terrain was very different, but the Hell you describe so perfectly was the same.

The Marines thought I was crazy and had a mission much worse than theirs, but I knew was the lucky one who would probably fly back to CanTho sometime that night.

Happy Birthday to all Marines…

Bill Gillespie

I hope I did not offend, or cross a line on my previous post…

Brothers,

Bill Gillespie

Bill, this is an open forum and I think the guys and gals who’ve been in combat, many who have written comments here,

are probably a whole lot more accepting of comments made ‘outside the box’ so to speak, than regular citizens. Your

comments are okay and you are most welcome here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Drop five zero, repeat H.E…..I was with D 1/5 Cav, 1st Cav Div October 68 to Feb 69. Most of our time was spent in the field – 3 weeks out, 4 or 5 days in a FSB. Our F.O. would set up his targets every evening – – I believe they were called Delta Tangoes (it’s been a few years.) The round would explode – shrapnel would whistle by and Lt. Moore would make that call: “Birth Control four three, Birth Control four niner. Drop five zero repeat H.E. over.” You wanted to have your hole dug and your steel pot on when “Four Niner” was setting up Delta Tangoes! 😎

I never used the phrase “Birth Control” over the artillery net although I knew it to mean

artillery pieces in general. I was pretty much a control freak user of straight physics out

of Fort Sill for my calling of fire. But then, I also changed a bit as time went on and I fell in

with the FDC personnel near the battery.

Thanks for the reading and commenting.

Semper fi,

Jim

Birth Control was the for 1/77 arty 1st air Cav,

My Call sign in 1969 was Birth Control 10 Bravo.

Cool Bob, to have that mystery cleared up. I thought it was slang when I was over there and did not know it

was a call sign. I was Colgate but in the field I seldom used any call sign because Russ at the 105s knew me

personally. The 155s were another story. Can’t remember the rest of my call sign and it’s nowhere in my correspondence.

Some things you’d think I would never forget and others I should not remember are right there in front of me.

Thanks for the reading and commenting.

Semper fi,

Jim

1/77 arty 1st cav /1967;1968

Thanks for the reading Ben and that supporting fire. Without Cunningham firebase (Army) I would not

be here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Hi James! I was with the 3rd battalion 18th artillery Americal Div. 1969.

We were a heavy arty battery.

Two 8 inch howitzers and 2 175mm guns.

I’ve been reading your articles.

From what I’ve read you had your shit together as an F.O!

Hey we were pretty good.

We could drop a 200lb round in your hip pocket!

Did you use TOT and H&I’s a lot?

I know one thing you could throw a lot of that state side training from Sill out the door!

Love ya brother.Tim

Yes, later on when I got back into Gonoi Island country and I could get

multiple batteries I used some TOT and it was devastating. The H&I fires in my

areas were assigned by the FDCs and not something I laid in at all. Thanks for the

support and the comment. And the reading, of course.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was wounded on go noi island in June of 68 ..

You are one of us.

A rare group of brothers all who paid quite a price on that small island that wasn’t an island.

And island of misery and death, only exceeded by the A Shau in the distance.

Thank you for commenting here, reading my stuff

and maybe finding some solace in this unfolding of reality you probably won’t see anywhere else…

and maybe not long for me if the forces that send people off to war get pissed off.

Semper fi,

Jim

I mentioned GoNoi to a buddy and he dropped his coffee. I was with K 3/1, he was with M 3/5. Hell on earth! Welcome home bro. Peace

You are the real deal Tom. I wonder if anyone around you knows or how you came

to accommodate life back here after what you experienced and learned. There are so

many interesting stories to consider. When coming out of hell you think home is heaven

but it could never have lived up to such expectations and then there was the fact that

the Gonoi stays inside us all, lurking….

Thanks for the comment and thanks for the reading.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was with a marine cap unit 67-68. We were about 5 clicks from Ben Son . All of our support came from ArmeriCal arty, and mortors. You guys were great

The Americal was life or death for me in the A Shau. They were superlative

at every turn. I cannot say enough good things about the Army in Vietnam.

Thanks for the comment and for the reading.

Semper fi,

Jim

I WAS ON THE USS RANGER IN 1961 OFF THE COAST OF VIETNAM. I WAS IN THE CATAPULT/ARRESTING CREW AND WE GOT ALONG WITH THE AVIATORS PILOTS AND CREWS VERY WELL. WHEN WE LAUNCHED OUR PLANES AND THEY CAME BACK WITH LITTLE HOLES IN THEM, AND WE WERE TOLD THAT THEY WERE DOING LOW LEVEL ATTACK TRAINING AND THE HOLES CAME FROM RICOSHAES, WE KNEW BETTER. WE LOST TWO AIRCRAFT DURING THAT TIME OFF VIETNAM. LATER YEARS WE LEARNED MORE AND MORE ABOUT THE EARLIEST “TRAINING” THAT WE WERE DOING. DURING THE GROUND WAR I HAD NUMEROUS RELATIVES AND FRIENDS THAT SERVED, AND I ADMIRE THE GRUNTS, BOTH MARINE AND ARMY FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY BRAVERY IN SERVING IN A DIFFICULT SITUATION.

On Dec. 1961 I signed on to the Marine Corp. I was declared 4f. I was crushed, all my relation were veterans. To this day I feel guilty not being there. Live or die good or bad I should have been there with the rest of you. Maybe it will help letting someone know how I have always felt.

Carl.

Those of us who ended up in the circumstance I write of, and others who preceded and followed me

into such circumstance, do not view you are you view yourself.

On the contrary. Almost to a man and women weare happy that you didn’t have to go and that you are alive and writing here.

The ‘thing’ about real combat, as you get from the writing, not many live through the experience and most who do live come home in pieces physically and psychologically.

You sound sane as hell and I hope you are happy.

Semper fi, my friend and thanks for writing on here from the heart.

Let it go….we did and do for you….

Semper fi,

Jim

You did not miss a thing. Look at it like this. God did not want you there and saved you for something or someone else. Be gratefully for what you have. I corps 68-69

I think Carl is most appreciative in his own way, at least those of us who actually did serve out there

think so.

semper fi,

Jim

Thank you Tom, that helped.

Man there is NO reason for you to feel guilty. The fact that you tried is all that counts. I don’t think that any of us who were there have ANY bad thoughts for you. I have several friends who were 4F for various reasons. They were my friends then and they are my friend now. Don’t beat yourself up.

My Mom sent me alot of instant coffee on a big weekly basis. I use to put in so much coffeeit was like paste but it got me moving.

God love your Mom!

Those care packages were gifts from heaven because they were from home, even if they were from somebody else’s home.

The people who sent them had no idea and maybe don’t today. Those memorized scraps from the packages and papers of the supplies stay burned into my mind to this day, like Brother John’s deep baritone voice.

He was never in the Nam, I found out later.

He was in Chicago the whole time I thought he was in Na Trang.

I though he was a black guy but he was a white preacher.

Amazing.

Semper fi,

Jim

Six days. A lifetime and a half, all in six days. Counting heartbeats instead of seconds and minutes. Hours not even calculable, let alone envisioned. Days in the past, mottled,stained, ugly, and too painful to recall. Days in the future beyond ken. I’ve said it several times already, and will again: I don’t know how you did it. I’m glad you could. I’m grateful you did.

John. I now don’t know how I did it either. The grace of god or something. Maybe

an alien looking over me from orbit. I used to dream that when I was in the hospitals later on.

Your words ring like the words of iron from the movie Josey Wales. “Days in the past, mottled, stained, ugly and too painful to recall…”

Neat stuff. That’s talent John. You reached right in and grabbed me.

Semper fi,

Jim