I had heard of the RPG (rocket propelled grenade), the Russian version of America’s recoilless rifle. Basically it was a small rocket fired from a shoulder mount. The rocket body, about two inches in diameter, had a warhead about four inches. Because the weapon delivered more than two pounds of explosives to any target under two hundred yards away, it had a lot of punch. My first RPG experience came right after the mortars stopped landing in places more distant from my hooch, and small gouging into the earth meant to serve as my foxhole. No self-respecting fox would have considered the mud pit, however.

A North Vietnamese soldier using a Soviet made RPG-2.

The RPG came in from the middle of a distant bright flare of explosion not far from the perimeter. The terror of the projectile wasn’t in its detonation, which was considerable, but in its exhaust gasses. The fiery trace of white hot gas came in not four feet over my head. Later I would swear that I felt the heat of its passing, as unlikely as that was. The detonation took place with a huge roar and the jungle became like day for a few seconds — just long enough to insure that I was night blind after it went off. No more than twenty seconds later, before I could recover, another identical monster blasted through the same air the previous nightmare had occupied. Instead of experiencing incoming tracer fire for the first time, like on the night before, I was experiencing rocket fire directed to explode behind me — as if the enemy knew I was a runner and was taking that possibility off the table. It wasn’t until the third rocket went over that I recovered.

The rest of the unit seemed to be engaged in exchanging small arms fire. I turned to Fusner who lay stretched out toward my position, the handset to his radio already extended from his hand out toward my own.

“Fire Mission,” I commanded. I rattled off what I thought to be the closest registration position while I clambered over my pack to get at my map and compass. I had everything I needed in my head except for a compass bearing. I needed to do the math between that magnetic bearing and the deviation required for merging grid north (my map’s north) to become true north. The guns fired on true north and when changing the position you claimed to need fire for, the calculations had to be accurate. A miss of only a few yards could kill a lot of friendlies, including you. I grease-penciled the numbers and finished the call, then waited past the ‘Fire, over” alert. The spotting round came in but I couldn’t place where it hit by either sight or sound. I was night blind and the rockets loud exhaust had made me deaf.

“Up fiver zero, Willie Peter, fifty meters air, fire,” I ordered. The round would be assured to be farther away than the last one and it would be impossible not to see fifteen pounds of white phosphorus exploding nearly overhead.

The round came in and my call proved accurate. I didn’t need to adjust further and fired for effect. I used my favorite ‘battery of six’ order. The rounds splashed in and the world shook for almost a full minute, with chunks of mud and jungle debris raining down upon us. The impact of the rounds had been closer than I calculated, which either meant that the first round had been off, or that we were closer to being on the gun target line than I thought. Aiming cannons and howitzers was like aiming rifles. The accuracy of direction, or side to side measurements, was easy. The calculation and achievement of range caused the difficulty.

I’d just called in an adjustment of up two hundred and a repeat when the Gunny yelled, “Check fire!” only a few feet from me. “You’re going to kill us all over a couple of rocket rounds.”

“Repeat,” I said into the handset, ignoring him.

Thirty-six more rounds came screaming in. Six sets of six, barely six seconds apart. We all hugged the mud. There was no mud or debris from the blasts this time. I’d gotten it right. At near the maximum range for the howitzers, their accuracy faded away. I’d work on doing a better job in the future.

“Shit,” the Gunny said, although with all the noise I was nearly deaf again. “You’ve gone bat shit again. Maybe it’s better when you run.”

I crawled into my hooch and wrapped the poncho cover tightly around me. I didn’t care about the heat and the mosquitoes seemed to have relented. Maybe the artillery was too much for them. I didn’t know. I didn’t care. I wasn’t going anywhere. It felt better to hug myself tightly and close my eyes. The Gunny left without saying another word.

“Call in the H and I,” I ordered Fusner, checking myself over for leeches. I’d been in the mud again but apparently escaped the vicious little monsters this time around. I wondered if we would get a replacement for the Corpsman I’d had to send home. We only had two now and I was worried about getting no care if I were injured. I tried to use my wife’s go-to-sleep relaxation exercises, but I couldn’t use them without thinking about her and I just couldn’t have myself thinking about her. I clutched my letter home to my leg. The Gunny had been right in his latest lecture to me in the early morning hours. I may not be running, but I was certainly of no use to anyone. Except for the artillery. I was good at the artillery. I hadn’t cared about any of that in training at Fort Sill. My wife had been about to deliver. We had no money. The car would not run. Oklahoma was too hot and we didn’t have air-conditioning. I got through the school because General Abrams’ (the tank guy) son taught the class, loved Marines (he was Army) and thought I was gifted in map reading and working the FDC. In almost every way artillery was founded on maps and map reading: Where were the guns, exactly, and where was the fire needed, exactly?

But things had changed a bit since Fort Sill, at least for me. Artillery was fast becoming more than a best friend. It was becoming my only friend. I rolled and felt a sharp pain in my right side. My other friends, M33s. In the morning I would find the Bong Song, no matter what, and get clean in it. My socks, my body, my boots and my .45. I imagined the Colt so filled with crud and mud that taking it out might make an enemy laugh himself to death — essentially killing him more effectively than if I shot him. I rummaged in my pack and pulled an envelope from one of my food boxes. I ripped it open with my teeth. Slippery fingers in the jungle weren’t meant to open metallic bags. Finding I had an envelope of John Wayne crackers, I laughed to myself. From his films and tough-guy reputation, you’d think John Wayne fought WWII almost by himself. In reality, he avoided fighting in the real war at all costs. I hadn’t understood his cowardice but now thought about the possibility of his good sense. I leaned out toward the mist, not hungry but eating the crackers in order to to have some normality in my life.

“This outfit have a Starlight scope?” I asked.

“Fifth Platoon,” Stevens replied. “They use it to set up their machine guns for fields of fire. It’s too big to put on a gun so you can’t do much aiming with it. Sees great in the dark though.”

Starlight Scope on M-14

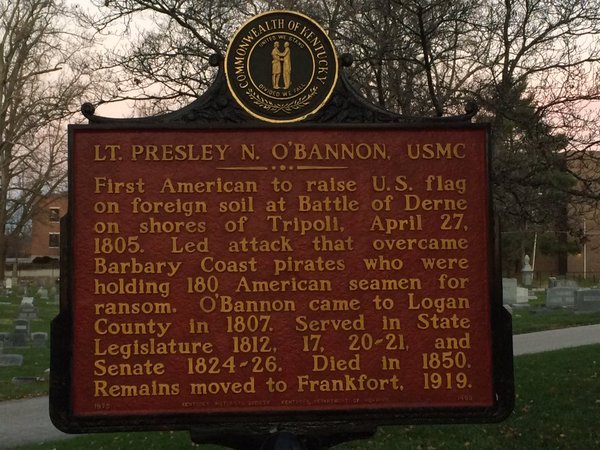

We’d had one at O’Bannon Hall, where I’d spent five months in Basic Officer Training. The starlight scope amplified ambient light dramatically. The inventors had been at the Hall training seminar and said that ground warfare would soon be changed forever because of the technology. Thinking about Presley O’Bannon Hall* drove a small dagger of whatever I had left for emotion up through my spine. I physically jerked before settling down. The memories of sitting in the coffee shop were so vivid, drinking hot coffee without regard for all the cream and sugar I might want. I wanted none back then. I drank it back. That was funny, too, in its way. I didn’t want black coffee anymore because I had to drink it that way.

“Star Trek” had played in the Hall every afternoon, following dinner every evening and before I fell exhausted into my bunk. I wanted to be Captain Kirk. What a commanding figure he was with all the answers for every problem. I remembered the guys who wore red uniforms. They went into the transporter as helpers or assistants on difficult missions to unknown planets. Extraneous, they had no real part to play except to die. They always got killed. Ironically I hadn’t become Captain Kirk. I’d become one of the guys wearing a red uniform.

I turned to Stevens, trying to shake off the thought. “Go to the Fifth Platoon and see if you can survey the damage done by the artillery strike.”

“Why?” he said without a sir, and in a tone that told me he would evaluate whether it was a good idea to go, and if it involved too much risk.

Anger exploded inside me, but it was too dark for him to read the homicidal thoughts I entertained at that instant. I knew I couldn’t threaten to kill him, or really threaten anyone in any way. Provoking such a terminal reaction would be disastrous, to be avoided at all costs. But that didn’t make resisting the temptation any easier. … Close your eyes, I told myself. Breathe in and out. Think about nothing…

“Lieutenant,” I heard a voice say. I looked up to see Fusner standing there.

“Did you take your malaria tablet, sir?” he asked.

I understood the basis of his question. Fusner was alluding to the few seconds I’d faded away, trying to get control of myself. “I’m fine,” I said. And I actually did need to take my malaria tablet. The awful medication, required to be taken twice daily, gave cramps, and diarrhea, and made some people dizzy as hell at times.

“The starlight,” I said. “I’ll need two compass points. One from the center of the impact caldera and one from the top of Hill 110.” A hint of moon broke through through the gravid clouds above, briefly illuminating the landscape — enough for a calculation. With my own bearing from my position combined with what would be brought back, we might survive the night.

“I’ll go,” Stevens finally decided, with no further hesitation. Before I could respond he headed off toward the hill, Nguyen at his side.

They looked like some sort of dark native ghosts, silent but dangerous as hell. But then, what wasn’t dangerous in this cursed place I’d found myself?

I thought about the calculations I’d need to make when they got back. I needed the bearing on the beaten zone the shells had made in order to have a physical registration point in the real world. Given the position I’d called in, and adjusting for the hundred and fifty meters up, or away from what was supposed to be my position, but wasn’t really, was vital to calling more artillery. I could adjust from the real registration point because basically the area I’d hit was the only likely area to be used by the NVA in the coming attack. It was dangerous as hell to call artillery from a fake position because the FDC would assume the adjustments were to be made from the ‘real’ announced position. A misplaced ‘battery of six’ would kill or maim everyone in the company, bar none, if delivered to the wrong point. It would be complete lunacy to direct fire on the move from the fake position. Hence the known point to be used as of a deviancy from that ‘real’ position.

I was a fake company commander, operating as a real artillery forward observer, using a fake position to adjust real fire on God knew who or what might happen to come along.

“Fusner, follow them and pace off the distance,” I ordered. I would need the exact point Stevens made his observation from to complete my calculations.

“Yes, sir,” Fusner responded, distinctly taking long strides when he left. I would be without a radio until he returned but I wasn’t planning on calling in artillery until he got back, and there was never any chatter on the combat net. That told me that there was another frequency I wasn’t being brought in on yet, but I would have to worry  about that at a later time.

about that at a later time.

Waiting in the darkness, mist and silence that followed, I took out one of the nasty little anti-malarial pills. I wondered if they really worked. The pill was bitter as hell so I gobbled down my remaining John Wayne crackers. When I got to the bottom of the tin foil back I found another little bag, heavier than it should be. I used my teeth to tear it open only to discover a cheese spread for the crackers I’d already eaten. Cheese Whiz. I sucked it down in one big gulp. It tasted awful but felt like home.

The moon broke through the clouds. It was half full. I wondered if my wife could see it where she was in San Francisco, which I calculated to be seven thousand six hundred and forty-two miles from where I lay. It would be daylight there. Sometimes the moon was visible in daylight but it would be unlikely that she’d be looking up at it in the mid-afternoon hours. I knew I wasn’t a hero and not much of a patriot at that moment because I would have accepted a bad conduct discharge from the Marine Corps if I could have shot up to that moon and then back down to the street just outside of our apartment in Daly City, only a mile or two from the Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore at the Haight and Ashbury Street intersection. The Corps could process my paperwork while I waited, seated just inside the Red Victorian Café.

A wraith appeared out of the dark, moving smoothly by, leaning as he passed.

“Where is everyone?” the Gunny asked, slowing to a stop.

“Needed some bearings,” I replied, knowing the answer would sound idiotic under the circumstances.

“Hope we don’t get hit until they come back,” the Gunny replied, putting one knee down on the exposed wet portion of the poncho cover. He wore his own poncho, which covered all of his upper body but made him sparkling visible in the night.

I didn’t reply, wanting to ask questions about where he would position himself in order to command the defense. Why I wasn’t allowed to hear what transpired over the combat net. Was he doing something about my upcoming date with death from First Platoon. But I kept my silence.

“You just stay here and stay down,” he said, before rising to his feet. “If they hit us, and they have to hit us before dawn, then depend on the machine guns and what you can drop on their heads with the artillery. We’re down on sixty mike mike ammo so the mortars aren’t going to do much in return fire. I’ll come get you when it’s over, or at dawn if they come through clean.”

“Anything you want me to do?” I asked, wondering why I asked as soon as the words were out.

“Don’t get hit,” he said, with a fake laugh, “and pray. Pray for no joy in the valley tonight.” And then he was gone.

I waited, taking another cigarette out to supposedly ward off the mosquitoes, although the mosquitoes hadn’t come back. I’d seen plenty of amulets on the men. Special pins, bracelets and necklaces. I’d majored in anthropology, the cultural park. The amulets were for luck or to influence the gods. It was common in lower social orders for the men going on the hunt or into combat to gird themselves with everything at their disposal before the actual event or challenge. All I had was my cigarette.

My team came silently back, the only noise of their approach being a slight squishing of the mud out from under their boots. I would prepare a simple artillery defense based upon complex but very effective calculations. I puffed on the cigarette to keep the fake mosquitoes away and I silently prayed that there would be no joy in the valley this night.

* Footnote:

Presley O’Bannon Hall, at Quantico, is named in honor of Lt. Presley O’Bannon USMC, first American to Raise American Flag on foreign soil.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

Just started seeing this story going around on face book and it grabbed my intrest and I read one chapter that popped up and then checked the menu and found I can read the whole book it’s been a hell of a read sir and I’m enjoying the hell out of it still haven’t gotten to the first chapter that got my attention but I will

Tom

THIRTY DAYS HAS SEPTEMBER, The First Ten Days, is out in paperback on Amazon. Thanks a lot Tom. Funny how some guys find out about the work way down the road and then

go back, like a television series on Netflix. Whom would have thought? Not me. The comment section is the best too.

Much enjoy writing back and reading the most treasured of opinions not shared anywhere else.

Thanks for being part of that…

Semper fi

Jim

James is this still under edit?? As I find things, I post, sorry if they have been posted already! Here is the one for this chapter I found “The pill was bitter as hell so I gobbled down my remaining John Wayne crackers. When I got to the bottom of the tin foil back I found another little bag, heavier than it should be: I am assuming tin foil back, should be tin foil pack??

Thanks for your sharp eye.

I believe many of the errors were caught in final edit prior to publication.

Appreciate your support, Mark

Semper fi,

Jim

By the way, I usually intend to read a chapter and end up reading 3. Great work. Thanks

Thank you Ira. The remarks made here do not escape my notice at all. I appreciate the supportive ones and puzzle over

some that I don’t necessarily understand as well. It’s always easy to accept compliments and shrug off criticism, although paying

attention to both often makes the work better, not only in editing backward because my memory is not perfect but also for the stuff I’m writing

right this minute.

Thank you.

Semper fi,

Jim

You mention Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore and Haight and Ashbury which I associate with late 1960 counter-culture, beats, hippies etc… Wikipedia mentions the Red Victorian was also associated with counter culture at the time. So my question is: Did you actually hang out in these places or was this intended as irony as to where you’d be after being discharged from the Marines. If you actually hung out there, then a Marine or officer candidate in that environment would be a story in itself.

I was not a Marine candidate when I literally hung out at Ferlinghetti’s small shop. I was recovering at Oakland Naval Hospital on my first

medical leave. I could not walk right and had to have four by fours taped to my center incision to go out (my wife taped me up in the morning so I could go out because I could not stay in). I went to the book shop because my wife was a beautiful hippy and they loved her. She made them sort of ‘take me in’ which they did. They were true hippies in that they loved everybody because they knew I was just back from the Nam. They were there when I got trashed on giving my speech at San Francisco State on ‘Revolutionary Development.’ I went to the store with vegetative matter all over my uniform and they helped clean the mess up so I could go home and not tell my wife. Cool. I loved those people and still have some of the little yellow books of poetry they churned out.

Thanks for reminding me.

Semper fi,

Jim

Oh, my wife went there because we lived only four blocks away and it was on the way to the park.

I quit taking my malaria pills, the orange ones, during my first tour and never took them at all my second. I never had malaria, but did have scrubtyphus, probably from the ticks they said. I used the mosquito spray on the leeches and it worked very well. Just melted them away. In one valley near Bong Son they were like a plague. About five years ago I went to Afghanistan and they had a new type of malaria pill, which I took for a while… I was stationed with the Marines at Camp Leatherneck and even though I’m an old Army guy, if I had to go overseas again I’d ask to be with the Marines. We contractors got treated better by them — in my opinion — than by the Army (I had been with them in Iraq) and I liked how they ran things. Also enjoyed talking with some of the Marines who were actually going out beyond the wire. They reminded me of me when I was much younger. Lots of memories coming back just reading your book. Good work.

We used lit cigarettes on the leeches. Those worked but not so well in the moisture and rain

when you had to keep lighting them. The leeches would hold on for about twenty seconds after the heat was

held to their backs. I never heard of the repellant solution, which now seems so logical and more effective.

We all heard that gasoline worked too but we didn’t have that. We did the leeches off each other like monkeys

picking through fur on one another. Funny images. Anyway, glad the Marines treated you so well. Most ex-Marines

are pretty damned special and I’ve met some great former Army guys too. I really like the ex-green beret types.

They seem to have kept their stuff together through the years.

Thanks for the interest, the read and the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

I spent many nights with Gen Abrams son at Blackhawk Firebase, he was he good guy. His dad flew in one day for a visit, pretty cool guy.

Abram’s sons all became General Officers in the Army. Which says something about

them but probably more about the Army. The one I knew at Fort Sill was a square away

neat dude, and I don’t know which one you are talking about. I never met the father.

Anyway, thank you for thinking and taking the time to comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

General Abrams son was an APC commander in 69. They tried to kill us with their 50 Cals. one night as we were moving in to reinforce their position.

Abrams son was a good guy. Very squared away and for some reason

he like Marines. He was tougher on the Army lieutenants because of

that fact, I think. Loved Fort Sill and the Army officers who

were so cool, not so up tight as my fellow Marine officers of the time.

Maybe a ‘Stripes’ kind of humor thing. .50’s were simply murderous on

the ground.

Semper fi,

Jim

We had to hump all of one night in a steady downpour about 18 clicks to get into LZ Penney on orders from on high. Got there about sunrise to find out General Abrams was coming in to review the LZ. They wanted us there with another company to make it look like there was a full company there. Got to shake the mans hand. I believe there were 4 cobras overhead while he was on the ground.

He came to dinner at my apartment with me and my very pregnant wife.

He was single at the time and a captain. But he was a cool guy and he

loved my 1966 GTO although would not drive it when I offered that night.

He didn’t drink either.

Semper fi,

Jim

The anti-malarial pills we got when I was there was “cloroquine-primiequine-phosphate”, a large orange pill that was taken once a week. Chloroquine was the stunt double for the laxative nobody needed. We also had little white pills. I don’t remember what they were.

Thanks Chuck. Yes, those big pills gave headaches too, and even though I got several bad ones I didn’t stop taking the damned things because I though

if Malaria got a hold of me out there I was dead for sure. I didn’t get the runs. Maybe my diet of ham an mothers!

Semper fi,

Jim

Great story. Keep it going. I can still see a leech rolling in a mud puddle. There were plenty of nasty critters in Vietnam. I guess the centipedes bothered me the most. During Monsoon all the critters went to high ground to sleep with us.

Semper Fi

Yes Jim, and I haven’t even gotten to the snakes yet. And the god damned ants that could not

be fought but only avoided. The monsoons were just awful. It was the only time we had suicides.

I learned later that the French had the same problems with the constant rains and without our

technology. I am pushing right on….

Thank you. Your comments mean a lot to me.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another Good Read…at least there were no Leeches….I am still feeling My neck for Leeches, as I read, and put myself there…..but Mosquitoes are bad enough…………and, Those Pills, for Malaria…Quinine I am assuming… Bitter beyond Belief……..!!!

Leeches give me the creeps to this day. I have these white circle scars they made under my

chin. People have asked over the years but what can I say? Oh, those are leech scars from

the mud in Vietnam. Now that would be a party stopper. Thanks for the kinds words Kay.

Love,

Jim