Night didn’t come easily in the Nam. The day had been a blessing compared to my first night. Moving seventeen clicks through muddy rice paddies wearing a fifty-pound pack was its own form of misery, but the brutality of Marine training had kicked in and setting one foot in front of the other had become a tweaking exercise of endurance. And I had endurance. What I didn’t have any longer was a useless flak jacket or utility coat, and wearing only a Vietnam issue green “T” shirt allowed the shoulder straps of my pack to chaff, cut and hurt like hell. Being the supposed leader of whatever this Marine Company had morphed into, I knew instinctively that there could be no show of weakness. I hunched and staggered my way through without comment and without water.

We were in the flatlands. From the ocean far away in the unseeable distance to the mountains inland, the land supported subsistence farmers trying to grow rice. Rice and small fish, with inedible fish sauce called nuoc mam (nook mom), were what indigenous locals ate all of their lives, along with noodles. My concern, with nightfall coming and the inevitability of attack facing us again, was where to set in. The soggy land prevented digging foxholes. The few spotted areas among the paddies of low hanging jungle seemed to be all that was left. My training told me that those would not work simply because they were the only places to spend the night. The enemy would know that. They would be registered (previously measured for range and declination) for mortar fire, if not heavier stuff.

The unit stopped just before sunset. I’d ended up near the rear for unexplainable reasons. I’d talked to no one during the arduous hike, preceded by my scouts and followed by Fusner, who somehow managed a full pack and the Prick 25 radio. The Gunny made his way back from the long line of Marines strung along the straight raised berm of the paddy dike. The dikes themselves were all wide enough for two people to pass one another side by side, but that was about it. The slightest misstep and a bath in the awful smelling paddy water would result.

The day itself was okay — dryer with no mist or rain. Although it was at least ninety-eight degrees, that was survivable and there weren’t any cloying mosquitoes. Except for a gentle moderating wind, all was quiet except for the radios. Many of the Marines carried small battery-powered radios. The armed forces network put out constant music moderated by a disc jockey I’d never heard of, Brother John. After one day in the bush, I felt I knew him well. Deep voiced, probably black with a slight southern twang, Brother John’s signature comment, made between every rock n’ roll or country & western song was; “This is Brother John, coming to you from Nha Trang in the Nam.” I didn’t know where Nha Trang was but I presumed it was close by. The fact that playing radios in a combat arena might alert any nearby enemy to one’s exact location seemed to not matter in this utterly strange war.

Everyone scrunched down on the dike into squatting positions, similar to the ones the local population used to relax. I found it weird to see the Marines all acting like natives while it was obvious they hated the gooks. I squatted. It hurt my knees but I saw the immediate value. The only alternative was to unfold my poncho cover and spread it across the dike or sit with my butt in the mud. Neither of those options worked. I squatted and endured more pain. The Marine Corps was all about pain and the handling of pain. Pain was good. Pain was alive. Pain kept you going.

“Coffee?” the Gunny offered.

I nodded, craving any liquid at all to quench my deep thirst. I laboriously unloaded one of my canteens from its cover and placed the holder atop the mud.

The Gunny half filled my holder with water. “Drink it,” he whispered. “They won’t notice.”

I drank the water as slowly as I could, looking around at the Marines, none of whom would look back at me, except my scouts and Fusner.

The Gunny broke out a chunk of white material. “Comp B,” he said with a smile. “Burns hotter than the idiot tabs.”

Composition B was the intense plastic high explosive invented after the Korean War. It was extremely stable and could only be exploded using a detonator. I’d never seen it openly burned before and leaned back a bit. The Gunny grinned, pouring water into his own canteen holder.

“Great stuff,” he said. “Won’t explode. If it did we’d never know. Twenty-six thousand feet per second. Powerful shit to toss down gook tunnels. A lot better than sending Marines down there. But don’t let the guys eat it. It’s like LSD, except they usually die from the trip, not that most of them care.”

I said nothing. I wasn’t surprised that the explosive was something more and less than I’d learned in training. There was nothing in the Nam that wasn’t a surprise. Nothing. But I knew if I could simply keep my mouth shut, I wouldn’t reveal my ignorance. The Gunny poured coffee into my holder. I was still thirsty. I drank the hot liquid greedily, not caring if it burned a bit. Pain was good.

“They got the message,” the Gunny said, looking at me over the top of his canteen holder. “The arty thing. I suppose you learned about the willy peter all burning up before it hits the ground in Fort Sill.”

I remained silent. The “Willy Peter,” or white phosphorus, doesn’t always burn up when the shell is exploded that close to the ground. Maybe at a hundred meters. I’d seen it used at Sill, but only in demonstrations. I hadn’t cared about it all burning up or not before it came to earth when I called the mission.

“The medevac picked up our casualties but they only dropped more bags,” the Gunny said, “Tomorrow’s drop will include water, food and morphine. We need the morphine bad. I hadn’t missed the muffled screaming of the night before. It had just added to the symphonic cacophony of horror.

“Why more morphine?” I asked. “Don’t the corpsmen have it already?”

The Gunny remained silent for a minute, sipping his coffee.

“You’re the company commander,” he finally said. “How’s this for it being your call? We have three corpsmen. Saunders, Johnson and Murphy. We get morphine once a week. Saunders and Murphy are out because Johnson used all his in the first couple of days.”

“He saw more action?” I asked, since the Gunny didn’t go on.

“Nope. He used it on himself. He’s an addict, apparently. So what do we do? Can’t send him back because they don’t take people back. Somebody else would have to come out. That’s not happening. Meanwhile, the men have their buddies dying in pain before dawn, waiting for a medevac through the night while they listen to the screams of their friends.”

“What’s my call?” I replied, trying to wrap my damaged mind around the problem.

“Can’t keep him here, can’t send him away,” the Gunny said. Gotta have morphine to survive. They can’t take him out because the other corpsmen won’t help them when they’re wounded if they do.”

“Dilemma,” I stated the obvious.

“Yep,” the Gunny replied, “most of this is all of that.”

“Where is he?” I asked, finishing my coffee, hoping for a second cup without having to ask.

“I sent him out with the point,” the Gunny said. The river’s not far ahead. We’ll set up a perimeter for the night once we get down there. He knows he’s fucked but I don’t know what to do about it.”

I presumed the point was a lead scout of some kind. In training we’d moved in unit formation of platoons, squads and fire teams. There had been no point. But then, there’d been no booby traps set into the beautiful pine-studded hills of Virginia, either.

“What am I supposed to do, I mean, as company commander, and all?” I said, hesitantly, accepting another cup of the instant coffee with silent thanks.

“Whatever you do is going to be wrong to somebody here. That’s the way it works,” the Gunny replied.

“Better you than me, kind of a thing?” I asked, fear returning to my belly to overcome my good sense of keeping silent so as not to show ignorance or to upset.

“If you like,” he said, finishing his coffee. “Let me know what’s what there. I’ll get the unit ready to set in.”

“We can’t exactly set in where we’ve been before,” I could not stop myself from adding. “It’s against all tactical reason.”

“You see any place else?” he replied, replacing his canteen on his belt and walking away.

Darkness descended and with it came my fear. When would we be hit, and where, and why didn’t anyone around me have an air of expectation or immediacy? Fusner, Stevens, Nguyen and I moved from the long paddy dike into a bamboo wooded area plush with reeds. The ground seemed solid. Marines spread out around us. I headed toward a small rise near the center of the area.

“Not there, sir,” Fusner pointed out in a hushed voice. “They’ll register that point for mortar fire, if they haven’t already. Go beyond it. It’ll be wetter but we’re wet anyway.

I did what Fusner suggested, pulling my heavy pack off and laying it down atop some sort of leafy mass of ferns. I unstrapped my poncho cover and spread it next to the pack. Finally, I sat down, exhausted. Nguyen knelt on the edge of the cover and carefully slid a plastic canteen to me. He motioned with his chin for me take it.

“You’re tired from lack of water,” Stevens said. “Drink the whole thing. We’ll have plenty of water in the morning.”

I drank the warm water tasting of iodine. I didn’t care about the temperature or the taste though. I listened to Brother John from Nha Trang, wondering about the total stupidity of playing tinny music out into the coming night, as if to send a sound beacon out to anyone around. Was there a curfew for playing the music or did it stop when Armed Forces Radio ceased transmission? I wanted to yell “Shut the fuck up,” at the top of my voice, but didn’t yield to the temptation.

I could call artillery, read a map and apparently little else to try to prove my worth in a Marine Company gone nuts. The Gunny hadn’t even bothered to fill me in on why we ensconced where we were or why we’d been ordered to move there. I pulled out my map and used a grease pencil to write grid coordinates running all around the current position. I waved Fusner over to me and called the battery to register our position at the Fire Direction Center. If I had to call for fire at night, then it would save time not to have to input our own position. I looked down at the map and the ten words and numbers I’d written down around a black point. The information seemed to fly up at me physically. It was inside me. Somehow I memorized the data, the map contours and direction. Surprised, I shut my eyes and it was still all there like it was imprinted on the back of my eyelids.

“Where the hell is the latrine?” I asked, not having eliminated anything from my body all day long.

“E-tool,” Steven’s said. “Nobody digs a trench on these stops. Just go down by the river and dig a hole. Make sure you’re inside the perimeter.”

“What’s the password?” I asked, unstrapping my E-tool from the back of my pack. “Just in case.”

Fusner and Stevens went silent and then stared at me together. Stevens spoke to Nguyen in Vietnamese. The Kit Carson Scout smiled. I looked back at all three of them in the dying light.

“Ah, there’s no passwords out here,” Stevens said. “Nobody out there speaks American and nobody not American comes through the perimeter in the dark.”

Marine training in a lush pine forest set among the rolling hills of Virginia was fast dying inside me. I found a marginally private spot among the bamboo groves to do my business. There was no way I was going down to the river and encounter the perimeter, although the idea of all that potential drinking water crossed my mind. That I could be thirsty in a constantly misting land where the humidity was about the same as pure liquid didn’t cross my mind as an analytical problem. It simply was.

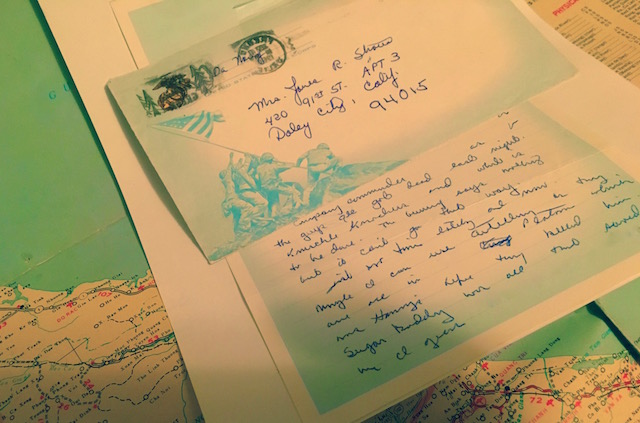

My small core group of men had found an area to assemble shelter-halves in a clump, little runnels dug around each one to allow the ever present water to flow anywhere else. I crouched down and set my back under the cover, then fumbled through my pack for writing materials I’d carefully stored in a plastic bag. I wrote my first letter home from in country. I didn’t have to lick the envelope to seal it. The weather of Vietnam did that for me.

I waited for the Gunny, my only contact with the Marines around me except for the scout group and radio operator assigned to me. I wasn’t a company commander or even a platoon commander. I had no command at all. I was a fucking new guy, FNG.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

Jim, just got out after 8 years infantry. It’s a strange adjustment for sure since it is all I’ve known since 19. I am reading this for the first time, and though it is a different war, this has made me feel less alone. Thank you for sharing brother.

Hunter. Yes, combat is a ‘brother’ kind of thing and I don’t think real combat, rare as it really is,

is much different from place to place and time to time. Thanks for clarifying that and bringing us all forward to

the modern times with this series of novels….set long ago but right now too.

Semper fi,

Jim

What unit were you with in Vietnam, James? So far I haven’t been able to find it on your site.

Been to the river, got trapped there in the middle of a monsoon,

We couldn’t get out , chopper couldn’t get in, got pretty hungry!

Yes, trying to get anything to come right down into the thick of that valley, especially when

it narrowed down or the weather was bad. Shit. Thanks for the real nature of your own experience

adding to mine…

Semper fi,

Jim

Glad to see you got rid of the flak jacket early. In 65 we went on our first mission to rescue the SF guys at Plei Me and we wore flak jackets because we were ordered to. The next mission we were told to leave them and I never saw mine again. On my 2nd tour we carried them to Khe Sanh in 71, but never wore them outside of the perimeter, just inside when we had incoming, which became every day. In a remark you mentioned your letters to home. My grandmother and an aunt saved mine from my first tour in 65/66 and gave them back to me as soon as I got home. A few weeks later while very drunk I got them out and burned them on the ground outside. I wonder what the neighbors thought. Fortunately my mother saved the letters I had written her and much later gave them to me so I still have them.

Yes, the flak jackets were hot, heavy and only gave an impression of stopping anything.

About as useless as a bayonet on an M-16. Today’s jackets work a helluva lot better I am told,

but still, without a cooling pack your can’t do the jungle shit. Sorry about the letters you burned.

I burned the only photos that I had early on in an alcoholic rage too. Must be endemic to the breed!

Thanks for the deep meaningful comment. I needed that just now…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, There is always another side to the flak jacket. On the first day of the tet offensive, an NVA regiment managed to break thru our perimeter at Bien Hoa only to be slaughtered by both AF & Army aerial & ground security forces. One of our security augmetees was caught off guard with his flak jacket open & became a KIA. His chief duties was that of a finance clerk.

The flak jacket of the time would not stop a 7.62X39 round, or much of anything else flying

around a battlefield, as many discovered belatedly. Your clerk probably would have died anyway even if

he had the thing closed. TET was a real challenge for a lot of outfits but the after action reports I got

all talked about how US forces conducted themselves pretty damned good, all except for handling the press reports

later on.

Thanks for the vignette.

Semper fi,

Jim

A great insight James. you must have written most of this down during your tour, I am glad you did. Eye corps 71-72

I did write some of it down on the backs of my maps (they were only coated with plastic on one side

back then). And my beaten mess of a diary which was sporadic at best. The most effective tool has been

the letters home. Even though I stayed away from so much I am able to read the letters and instantly place myself

right there, like tonight on that overlook of the A Shau. My son reminded me, after reading the last segment, that

I’d told him all about the Kamehameha Plan when he was a kid on Oahu. I had no memory of that until he told me.

It is surprising to have the family reading this and being surprised too. Most of it has just lain there like

a waiting section of swampland, to be gone around and not through.

Thanks for the comment and your support.

Semper fi,

JIm

Like Jim above, turned 18 in ’74. I am enjoying your writing. My cousin flew 2 Cobra Tours. Don’t know how you guys did it. I always wonder how I would have responded.

Thanks for your writing.

Like the class act your probably are Jaxk! Good people are good people and you can’t do much

to fix the bad ones. Not in combat, anyway. Thanks for commenting so openly and from the heart.

Semper fi,

Jim

Never had the honor. Nixon ditched the draft in 75 I believe . Turned 18 in 74, registered and waited. Know many vets who came home and always blown away with their accounts. A real shit sandwich.

Jim, glad you didn’t go because here you are, in one piece and sane! Vietnam was quite something for so many of us. In fact it was so much a something

that I don’t know anyone who came home ‘quite right’ after being there for awhile. Thanks for reading the story and writing on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

So Descriptive. You really have a gift.

Thank you James. For the reading and the commenting. So many people simply remain silent, but that is also very

characteristic ofthose who went out into the shit.

It’s a tough subject so filled with unbelievable crap

because the mythology we’re all taught is so

filled with bullshit.

Semper fi,

Jim

Good read so far

Your comments keep me at it Dean!

Semper fi,

Jim

Amazing story..

Thank you Sally…

A ground pounder.