The Ontos moved forward, with the Gunny swinging both armored back doors of the tracked vehicle closed behind him. I followed, slowly dropping back as the vehicle picked up speed, to stay clear of any back blast. I’d wanted to ask the Gunny if I could use a spare M-16 left over from one of our casualties but hadn’t pursued that request. I felt naked on the mud flats with only my holstered .45, even if its leather hold-down thong was unsnapped. There was no enemy fire as the attack began. I watched the dawn bring evermore light through the misting rain, with all the Marines in the company moving forward. There was no crawling and no zig-zagging back and forth to attempt to take advantage of available cover, because there really was no cover. A six-inch high clump of bamboo or other assorted jungle plant growth, would not hide a sizeable raccoon, much less a Marine with helmet, weaponry and carrying a full kit on his back.

The company was properly spaced, each Marine just about equidistant from those around him. Not like in training at all. Trying to get Marines in training to stay out of clumps, or naturally congregate together, had proven impossible for training officers. But down in the A Shau, with the chips all on the table, where winning meant getting to stay alive to see light dim and pass into full dark, the Marines acted like the kind of Marines I’d never known back home. They weren’t organized in any kind of orderly fashion and they were so tattered and dirty they were almost unrecognizable for what they were, but they were quietly effective in almost every way, from movement, to fire control, distribution of supplies and more. And the fire they delivered was amazingly accurate since I seldom saw anyone actually stare through the fixed metal sights set on top of the barrels.

The Ontos wasn’t mired down, as I’d first thought once it stopped moving through the fairly dense jungle growth. The jungle growth was thick but not too thick to inhibit tracked movement. There would have been no possibility of the small but heavy armored vehicle cutting through or crushing past the kind of triple canopy jungle that existed up on top of the canyon walls and descending down almost all the way to the eastern sea shore. The Ontos had stopped to reload 106 rounds. The team of supply handlers the Gunny had sectioned off to recover the strewn mess of the night helicopter run, were being quickly effective in getting to the flechette rounds and getting them loaded into the empty chambers of the long guns.

The NVA Soviet or Chinese origin .50 caliber firing had stopped after the Ontos had unloaded the last four flechette rounds into the jungle area where the heavy machine gun was suspected of being placed. The Ontos only had 13mm armor, but the front of the small beast was slanted, thereby doubling its stopping power. An armor-piercing heavy machine gun round would penetrate the sides or the bottom of the Ontos easily but not the front glacis, which was the primary reason that, once the NVA .50 opened up, the Ontos went directly at it.

I felt more than I heard Cowboy’s first pass. The low giant of a noisy aircraft did not come speeding in, which normally would have had its radial engine blasting and reverberating back and forth between the canyon walls. The plane was almost quiet as it came down. I looked up and behind me, when I felt the plane, and then quickly coming to understand what Cowboy was doing. The Skyraider was dropping down at near idle, it’s big beastly shadow descending like some monstrous bird of prey. I ducked down and shivered slightly at the sight, but could not look away from its approach. The plane was descending with its nose higher than its tail, all of its flaps fully extended, moving through the dense air and rain so slow it seemed to be a giant artificial prop being added onto the set of a Hollywood war movie. I understood what Cowboy was doing. He was giving us as much time and cover to cross the mud flat as he could, instead of speeding on by after spraying a few hundred of his deadly but sparse 20 mm cannon rounds of ammunition, and, while doing so, he was able to see us making sure he wasn’t hitting us instead of the NVA.

The plane fought to recover itself in mid-air, still dropping, until it was only a few meters off the ground before it leveled off and seemed to float right into the jungle in front of me. The feeling the Skyraider gave me was one of core-penetrating terror. All I wanted to do was smash myself into the mud until it passed. But it was Cowboy, and the Skyraider he flew was U.S. Navy. The enemy had to be feeling the same fear that was running up and down my spine, but even more so since they knew the weapon was intended to kill or maim them. I got up and ran forward, staying low but moving fast. There was no order to run that I heard, but every Marine in the company, not riding in the Ontos, took off with me.

The Skyraider’s monstrous radial engine screamed up to full power, as it accelerated to maintain its low altitude. There was still no strafing fire, instead, bombs were pickling off the plane’s wings, one after another from each side. They began to explode behind the plane, as it sped directly over the center of the jungle vegetation.

The shaking tremor of the explosions ahead drove me forward toward them instead of down again. Wherever those bombs were going off I knew the NVA would not be quietly and lethally waiting. They’d be down flat or underground inside their snaking tunnels and cave complexes. I was a lot more fearful of being killed by the NVA coming out of their holes than I was by being damaged by the bombs.

Once in among the debris, still filtering down through the morning’s moisture and rain-laden air, I slowed to avoid overtaking the Ontos and becoming more of a target or injured when one of its 106 recoilless rounds was fired.

There was no crawling through the kind of jungle we were in. I moved huddled down, my knees bent down as far as I could bend them and still get ahead, while my torso was slanted as far forward as it would go. I could not keep loping or running as the load I carried was too heavy to support anything but short stretches at maximum output. I followed the Ontos in its left track as best I could, although the jungle growth, even at my distance, still snapped painfully back and forth. I realized that the part of my plan that had both platoons opposite one another, one against the face of the cliff and the other moving down the river bank, firing into the center-placed jungle to suppress the enemy, was impossible to implement, not without killing Marines in our element moving up the center. I’d forgotten about the speed of the Ontos. The machine could move through the thickness successfully, but it had to maintain speed and use momentum to make it over and through the heavier areas.

The center attack group, of which I was a part, led the attack and had to depend on the flanking forces not to fire into the center if at all possible, which was the opposite of what they’d been instructed to do.

The whirling Wright engine of Skyraider quieted as it gained distance from our position following its run. I knew it would be rising to gain altitude, make its pylon kind of turn, and then return to dive into another run. Each pass would come in as we moved ever deeper into the jungle’s interior, giving Cowboy less and less visibility of exactly where we were because of the weather and the increasing density of the foliage. The jungle had to be fast becoming a roiling messy mantle of concealment, at least from Cowboy’s perspective. It also provided concealment from those on the ground, and that meant recognition problems about whether the personnel was NVA or Marines.

Small arms fire, mostly muffled but still loud, sputtered up and then died down around me, as I moved. Brilliant muzzle flashes burst across the area just to my front, the passage of bullets themselves unheard, but their presence so physically evident that my body needed no instructions to hit the ground. My face went into the stinking smelly debris first, the aroma almost welcome because of the gut wrench of fear that had returned, like white-hot lead being poured up and down through my core. The rest of my body wedged down, trying to reach the center of the earth, or something close to that.

I went down soft, however, because there was nothing hard under me. The weird sticky layer of mud cradled the broken, hanging and half-crushed foliage, allowing every obnoxious smell of the jungle to be opened like an aged-out tin can filled with bad fruit or putrid sardines. The firing had come from my left, automatic rounds sounding more like a chainsaw than a machine gun. I knew the NVA were only yards away and I couldn’t figure out how they’d missed me moving by. I wasn’t moving by anymore. The rain beat down on my helmet. There was no point in looking up because the brush was too thick to see through, and looking up might draw more fire. If I still had any M-33 grenades I knew I’d have thrown them, no matter how undependable the fuses might be or how close the detonations might occur. But I had nothing more than my Colt, which was so inadequate that I still hadn’t drawn it from my holster, even in the face of nearly direct fire. I was more afraid of losing the only weapon I had than using it to shoot back at anyone armed with a submachine gun. There was no screaming, so I presumed that nobody nearby was hit. Nguyen came out of nowhere to slip in beside me. I looked at him across the few inches that separated us. His eyes remained black and unblinking. He pointed back behind us. I felt more than heard Fusner creeping forward. Nguyen pulled something from his blouse, fiddled with it and then threw it upward and out in the direction the AK fire had come from. He didn’t bother to duck so I didn’t either. The muffled whump of the grenade’s explosion threw debris back over all of us.

I wondered how to say “tell me when you’re going to toss a grenade” in his language, but I knew it was a waste of time. Nguyen had calculated that we didn’t need to duck and he’d been right. Again. He motioned me forward. I crawled. I wasn’t getting up to my feet again until I was out of the hellish jungle, although I also knew immediately that the Ontos was pulling away in front of me. I didn’t want to lose the Ontos. It attracted the heaviest fire but it seemed charmed to be able to kill without being killed. As some of the men carried charms with my stuff inside, I wanted to remain in the close aura of survival surrounding the fierce little machine, even if it was an illusion or based on nothing more than hope.

Suddenly the rain stopped like it was controlled by some heavenly spigot. But there was no sun. With the rain stopping, even with the gray overcast of the cloud cover allowing for only a bright twilight sort of existence down in the valley, I realized I had not seen the sun in what seemed like a week. That the rain was gone, at least temporarily, made two things immediately apparent. There would be no dryness resulting throughout the length and breadth of our move because the jungle was so full of absorbed moisture that anything dry that touched any part of it would instantly become soaked through. Everything, from ferns to the leaves and all around, and on any overhanging bamboo fronds, bled water. The second thing was the smoke. Separate tendrils of thin blue smoke rose twisting and turning in the mild wind from different spots in the jungle around us.

The Ontos stopped its forward progress, and the two heavy armored doors on the rear of it sprang open. The Gunny jumped out and loped toward me. I noted that he didn’t carry an M-16 either or anything but his sidearm either, and he had no pack on his back.

“Resupply,” he said pointing back the way we’d come. “The satchel charges. We need the charges.”

“What?” was all I could manage, my position crouching down in the jungle debris for cover, making my question more of a plea than I meant for it to be.

“There are satchel charges in the resupply,” the Gunny indicated, dropping his finger.

“Jurgens,” the Gunny said, as the sergeant approached from behind where Fusner had taken up a position just back from me. “The smoke. The smoke is coming up out of their tunnels. The Skyraider pass bombed the shit out of some underground supply cave down there, and its burning. The smoke is coming from the tunnel entrances.”

Jurgens disappeared, as I rose up to higher crouch to look around. I could see four tendrils rising, although not exactly where their bases were in the rough foliage.

“Holy shit,” I breathed.

Without having the flanking fire of both platoons moving south on each side of the jungle area I’d once again lost hope of making it alive to where Kilo was about to descend to ‘relieve’ us. The NVA, confronting us directly, could face our small arms fire, machine guns, Ontos fire and even the strafing of Cowboy’s Skyraider, and then go right back down underground to wait until one of us, or more, passed by a tunnel entrance. Firing from their hidden entrances would be lethal. We would be defenseless.

Marines came from behind us, carrying green cloth sacks. The sacks were different from the containers explosives usually shipped in. The sacks were about the size of briefcases except made of green-dyed canvas. I looked at one bag closely. The black stenciled printing on the broad side of the bag read: “Large Assembly, Demolition, M-183.” The Gunny undid the straps quickly on the side of one of the bags and pulled the top open. I saw white demolition cord sticking out of eight rectangular tubes wrapped in a brownish paper. I knew the sticks were composition B because of the color. I also knew the sticks were probably one pound each. Eight pounds of Composition B was a lot of explosives.

Jurgens re-appeared, carrying more canvas sacks. He set them next to where the Gunny worked. The new sacks were thinner and wider than the satchel charges and they had two flaps each instead of one.

“Claymores,” Jurgens said with a grin. “Finally gonna get some with these babies.”

The Gunny worked quickly, his hands moving almost too fast to follow, as he opened sacks and adjusted the contents of the satchel charges.

“Forget setting these off conventionally,” he said to Jurgens. “Let’s use the Claymores and command detonate. Simple and safer.”

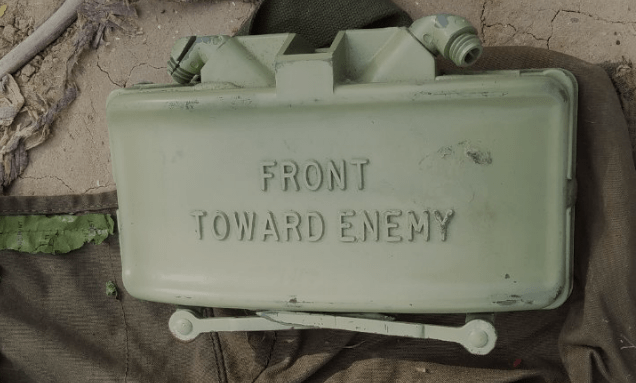

Jurgens opened a claymore bag and pulled the green plastic device out. It was molded smoothly and curved attractively. I remembered well the look of it from training at Quantico. 700 small steel spheres, embedded behind the plastic face, were driven forward by a pound and a half of explosives. Both sides of the device had raised plastic print with instructions about which way the device was to be placed or pointed.

Jurgens unloaded the Claymores, quickly but efficiently wrapping their attached wires around the body of the satchel charge bags. His men crawled forward, each clasping one of the combined packages in his arms, making no effort to be gentle or handle them like the terminally deadly devices they were.

“All right, get out there,” the Gunny ordered. “Jam one package down every hole the smoke is coming out of. Run back ten yards, drop down, and then crush the Clacker detonator twice. If you shove the whole thing down the hole you shouldn’t have to worry about getting hit. Then, get back here and get another charge.”

I watched from my position flat on the jungle floor. I knew the small lever detonators had to be levered shut twice to set off the Claymores, as a safety measure, but I hadn’t known they were called Clackers. The Claymores added to the already significant number of explosives in each pack. I hoped that the ten yards was far enough to be from them when they went off.

“We’ve got to move fast,” the Gunny yelled, standing to be heard by everyone, “that smoke won’t last forever. Let the M-60s and the Ontos take care of anyone dumb enough to remain on the surface.”

I crawled up to my knees and got to my feet, the fear from my close call with what I assumed to be an NVA trooper above ground, not dissipating at all. I knew my right arm was shaking but I didn’t think the effect was visible.

The Gunny came close to my side.

“Get your sidearm out,” he whispered. “We’re going to move fast behind the Ontos. Those underground rats are going to be coming up, coughing, blind and probably deaf. Shoot at the center of mass, no matter how good you are with that thing.”

I pulled out the Colt, my hand closing over the butt as I withdrew it from the wet slimy holster. My arm stopped shaking once the Colt was firmly in my grasp. I caught the Gunny’s glance down and realized he’d seen my shaking. He was helping me cover the shaking so nobody else would notice.

“That was AK fire,” he said. “The crack and no tracers. Not one of our guys.”

I made no reply, remaining silently thankful that the Gunny had bothered to relieve my mind. I knew he was correct in retrospect. The sound of the AK was very distinctive and the NVA didn’t use tracers in their submachine guns.

The Gunny ran forward, his own sidearm out, flocked with a small group of Marines surrounding he and his radio operator closely before they almost magically split away to blend individually into the bush.

The explosions from the satchel charges began to go off, each one exploding sharply, throwing mud, water, and foliage high into the air. I walked fast, the sky falling around me. Fragments of the jungle had replaced the rain pelting my helmet. I scanned the area in front of me, Nguyen to my left and Fusner just back on my right. Nguyen’s M-16, held out in both hands, pointed wherever he looked, while Fusner’s weapon remained under his left hand at sling arms. Fusner’s right hand was holding the radio handset in case it was needed, with the headset to the AN-323 spring tensioned to his upper arm.

The Skyraider came in, luffing through the air like before, in the strange flying style Cowboy was a master of, allowing the giant metal monster to get lower and slower so the pilot could see and then drop more bombs. When the big radial engine kicked back in, the noise was overwhelming until the Ontos fired two rounds and more satchel charges went off.

My ears hurt but, for some reason, my frightened insides weren’t quaking in terror anymore. Being in the center of the combat I felt like moving through a sunken stage where just around and above me, all different symphonies of raucous music played. It was as exhilarating as it was frightening. I was half blind from the flashing of muzzles, explosives, and particulate in the air. I was half deaf from the booming sounds of coming from just about everything, but I was also moving, thinking and not running away. I hunted for anything I could see that might need my attention, as we worked our way down the peninsula of jungle growth.

I didn’t have long to hunt. The Ontos had veered to the east, as we traveled south down toward the cliff face where Kilo had to be considering its descent into the hellish A Shau Valley. A still smoking ruin of a broken messy crater was just to my left, which was remarkable but I didn’t give it a second thought because the satchel charge that made it would certainly have killed anything close when it was set off, below or above ground. But that wasn’t the case.

A uniformed NVA ran through the shoulder high bracken, seeming to slip through a crack in the reeds and tall elephant grass that couldn’t have been there.

His head was bare and across his chest, he held an AK-47. He stopped suddenly only feet away when Nguyen fired several rounds into his chest. The man stopped in his tracks but was still standing, his facial expression flat and unchanged, as if he’d run into a wall. I brought up my .45 smoothly, slowly squeezing the trigger as the automatic rose in my extending arm. As if by perfect design, the Colt went off just as it came level with my shoulder. The NVA soldier was literally blown back from where he came, his head tossing so far back it seemed to disappear. I moved forward after him into the reeds, pulling them aside with my left hand, using my right to point my weapon downward. Nguyen went low and slid under my extended arms. He leaned in close over the body before pulling back. He tapped his forehead when he stood. I understood. I’d hit the soldier in the forehead. Nguyen nodded so deeply it was like a bow, before pulling back and loping toward the Ontos. I followed because his left hand was pulling me powerfully along. He’d grabbed the sleeve of my right just back from my elbow and would not let go.

For some reason, I didn’t want to leave the scene, but I only took one glance back before crouching low again, pulling my sleeve loose, and then picking up the pace to pull even with Nguyen and catch up to Fusner. My ears rang from the M-16 and .45 automatic fire that had occurred so close. I couldn’t get the dead soldiers expressionless face out of my mind as I ran, but I also felt that I had done what I was supposed to do for the first time in many days.

The Gunny came up from behind me, moving fast to catch up with the Ontos.

“Nice work,” he murmured, as he passed. ‘You and Cowboy got lucky, thank God.”

I tried to remember whether I’d fired just the one shot from my automatic but couldn’t. Did I need to reload? And I hadn’t seen Zippo in some time. Was he all right? The battlefield was all blending together and I was having a hard time trying to take in the idea that we had no real visibility of the flanking platoons moving along the valley floor under the cleft of the cliff, and also down by the river. I couldn’t see most of the Marines who were attacking with me down the very center of the jungle area either. Quantico training in field combat had been so much easier in the open forest areas of Virginia where almost everything had been visible.

The enemy fifty-caliber hadn’t fired another round following the twin blast of flechettes from the Ontos and that was more than just a minor relief. It meant that the NVA was down, probably hidden away until we passed. I moved faster to get closer to the rear of the noisy roar of the Ontos’ engine. Cowboy came back for another run but this time he didn’t allow the Skyraider to slow and drop bombs. This time the 20mm cannons mounted in the thing’s wings poured fire down into the jungle ahead of us.

It was a satisfying sound but even more satisfying was looking up to see that the loitering plane still had what seemed like at least a half a load more of bombs and other stuff hanging from under its wings. Cowboy would be coming back time after time. We might make it to the end of the jungle area.

Small explosions came from up ahead and the Ontos slowed. I moved, with Fusner and Nguyen to flank the machine, fully aware that standing directly behind it could be disastrous if it fired any of its guns again. I tried to peer forward through the leafy brush and bamboo but it was useless. There were no easily visible smoke trails, as we’d passed that part of the burning underground tunnel complex. Marine M-60s opened up from both flanks. The explosions I’d heard had to have been grenades, and those hadn’t sounded like American models. The ChiCom grenades the NVA carried made bigger luffing explosions than U.S. inventory, but the weapons were plagued by duds because of their water sensitive friction fuses. The body of the German type “potato masher” Chinese variants were poorly machined and carried no fragmentation wire inside them.

Although I could not see all the elements somehow coordinating in our attack, I knew they were there and the attack was working. The good fortune of the underground fire, the brilliance of Cowboy’s single Skyraider performance and the dogged endurance of a tattered but hardened Marine unit made up of many deeply disturbed and frightened men was proving to be overwhelming. The NVA had, once again, underestimated just how tough and determined the company could be when backed into a corner.

The rain began pouring back down as Cowboy brought the Skyraider back down to start another run. I moved into the scattered mess of jungle behind the Ontos, more like an armed predatory spider than a uniformed human combatant.

I believe it was a bad move going from a 45acp to a 9mm ..Especially using fmj ammo. I test a lot of different ammo for .40 .45 and 9mm and they all do well with the correct ammo. It’s only common sense that a big 230gr ball is gonna do way better at stopping a threat than a slim and sleek 115gr 9mm. I personally carry my 1911a1 in 45acp as my self defense sidearm. From what I’ve read yours didn’t have any problem stopping the threat.

Physically handling the .45 Colt under the worst conditions and in the greatest need I must say that the weapon

was perfect in doing what it was designed to do. I can’t imagine a 9mm performing the same way.

Thanks for the ballistics back up.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, as a former B52 gunner I remember watching the results of our bombs looking for secondaries for the BDA report. I always wondered what it was like to be near a full on Arc Light strike. Having read your work I no longer wonder. I hope what we did helped somewhat.

Thanks Tom, and I’ve written the books partially to settle some issues and reveal the unknown mysteries so many

experienced and have no answers for.

Semper fi,

Jim

Is this based on your experience in Vietnam?

Yes, Thomas, I am afraid so.

Be a bit hard to do a total fiction piece on this and then have all the guys

who were in the shit too comment the way they do.

The credibility and quality of the work is in these comments. and I treasure them.

Semper fi,

Jim

Ok, LT, withdrawal has set in and I need another fix on this. Help me.

It’s coming

Ok, LT, withdrawal has set in, help me out here, I need another fix,

Okay, okay, you will have the next chapter tomorrow. Back at the cliff that has so come to remind me of the Jack in the Beanstalk fable.

Thanks for caring and waiting…

Semper fi,

Jim

All 16,400 comments. I have answered them all!!!

James,

Thanks again.

Hope all is well, take care.

Glenn

Thanks Glenn, much appreciate the care and writing it on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

I’m not sure I understand why you would feel it necessary to ask the Gunny if you could have one of the spare M-16’s to carry. Without a doubt he wants you to remember your fire support job, but you also need the ability to defend yourself or you won’t be there to do your job. The marine carrying it would have been happy to give it and a few magazines to you to lighten his load. While I love a 1911 Colt, I would feel somewhat under-armed in a frontal assault out in the open. In ’68, my MI partner and I were with a dismounted tank platoon about 5 klicks south of the DMZ chasing VC that had buried an undetonated 155mm round in the road to take out a tank. As we were moving through the light forest I looked at Bud and his .45 and thought, “I know how he shoots. I bet he wishes he had an M-16 along with that .45.” I think I know how you probably felt about then.

The Gunny was right, just lake back here in the ‘real’ world. The gun draws the orientation to personal safety to the exclusion of what may

be the necessary survival mission for all around. The .45 didn’t do that. I wasn’t there to be the infantry, anymore than the public, by and large,

is not there to be police.

Semper fi,

Jim

Just got back from a reunion with 20 Vietnam Vets from E battery 82nd Arty 1st Cav.

It was as if we had never went our own ways. The feeling you have for one an other who you shared

The specter of combat together is unmatched. Four days of memories, hugs and yes kisses. Leaving them was had just as much mixed emotion as the first time.

So happy for you and the guys. I have heard of such trips but fear taking one myself.

thanks for writing about the joy the trip gave to you and the others…

Semper fi,

Jim

I had went to a reunion (once). For me it was a bad experience! It brought back memories that I had tried to hide for many years. Each one of us has thier own way of dealing with past experiences. If you do not attend that is fine, don’t feel you have to. Sometimes avoidance is best. Each one of us are individuals. For some it helps, others NOT. I was a NOT!

Great to see you back at it. Great job James. Back to VA today the new Dr. just don’t know at all all about what we had to go Through. Know one knows if they were not out in theBoonies and the things we had to do just to stay alive. There was no hope of getting back home right up until the last day. Then when we did get back we had to Learn how to fight demonstrators Great job my brother

Demonstrators would have been easy. Never re3ally saw any except for the one time I spoke at SF State that day.

What was harder was the regular people who did not give a shit or looked down upon us without really looking down upon us.

And coming back to no real job of import and no recognition for anything.

Semper fi,

Jim

it is amazing how deep you can get in the mud when the lid starts flying I know I was pinned down for three days and three nights my cowboys came and they would work all day The phantoms come and work to then at night we had artillery all night long and airplane flew over night drop Parachute flyers to make it light for us to see We had just a company and they had a regiment

Thanks Fred. No shit, are the words I want to use to answer. Thanks for the great comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

“Exhilerating as it was frightening”….. such simple words…and yet they are what describes us so clearly…the words that define the very souls of those warriors whose boots have been on the ground…. and have seen the elephant….many come home and struggle to stay as far from that cacophony of memories that batters their souls…and so many others that willingly seek it out…Fire fighters that run into burning buildings…the Peace Officers that charge forward to the sounds of gunfire…Missing that adrenolin rush that cannot be duplicated in any other way…and that is the difference….that is what makes us who we are, and who we will be for all our days…and nights…we will always be walking those trails Lt…Semper Fi

It is so good to read your words of brilliance and light again.

You, as usual, have such a talent all of your own.

Your description inspires me and I thank you…

Semper fi,

Jim

The Wall That Heals, a 3/4 scale replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, was recently in Fairfield, IA. I placed your two books (in ziplock bags) and a candle at panel W-42. The thought was to honor those listed; to provide a link to those who survived and may visit; or for next of kin. Two nights I stood vigil from midnight to 4 AM to assist any who might come. I read aloud all the names on that panel. I carried that panel when we disassembled the Wall. Much coming together and emotion expressed by all associated with the occasion. If it would be useful for you to have those books I will send them.

Be Well.

Wow. That is just something Dan and I cannot thank you enough, nor many of the guys and gals on here.

What a wonderful tribute and action straight from the heart. I don’t know what to say but I am with you brother…all the way up the hill…

Semper fi,

Jim

You know Dan, I was having a kind of bad day.

Not anymore. You gave me perspective, which is so easy to lose out here in this phenomenal world.

That panel is from the real world.

And those men died while trying to make sure the rest of the people in this country would not have to, the way they saw it.

The other stuff of today…forget about it.

Those books, if you sent them, will be placed on a special shelf of my library as

a monument, not to me or my writing, but to those guys, that time and that place in that time…

Semper fi, brother

Jim

James, The books will be in the mail soonest.

Blessings & Be Well.

Thanks Dan and I much appreciate this…

Semper fi,

Jim

Much of what the Gunny is imparting to Junior could be found in the words my Dad, a decorated Korean War Combat Vet NCO, conveyed to me prior to my first platoon and subsequent Battery commands. I have had the same talk with my son, who is on his 7th Combat Deployment. I sent him books 1 & 2.

To be associate with your Dad is such a wonderful compliment and I cannot thank you enough George!

Semper fi,

Jim

To Dan C:

Hand Salute! Ready 2!

Semper Fi!

Thanks so much for that snappy compliment, sir!

Semper fi,

Jim

👏👏👏👍👍👍👍👍👍👍

Made a couple of frontal assaults on Goi Noi in 68 on operation Allenbrook. I know the emotions you are expressing. Good writing!

Craig

Lima 3/27

Thanks for that entry Craig and thanks for the compliment…

Semper fi

Jim

Another great read James thanks

Very good Sir! Thank You

Thank you, David.

Semper fi

Jim

Sorry about my tardiness of late Jack, but I am getting caught up now…

Semper fi,

Jim

Nothing to be sorry about. It all comes as it is meant to be.

Semper Fi Sir

thanks Jack!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

I am a peace time Air Force veteran who has always had respect and admiration for all veterans. The men and women who were placed in harms way in service to our country will always have a special place in my heart. I have read and wait to read every chapter with eager anticipation. When out and about and I see men with their Vietnam Veteran hats on, I thank them for their service and tell them about your Thirty Days Has September and give them your name so they can read too. Thank you for sharing your talent and experience.

Thanks for the nice comment and the great compliments you are paying me.

Keeps me going.

Semper fi,

Jim

Just throwing this out here. I know you reply to all comments, but the past few on 30 Days and Island in the Sand have had no response. Just checking.

Got then Jack. And thanks for pointing that out!!!

You are important and you do mean a lot…

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks for the response Jim. I thought I screwed it up when submitting or maybe a problem with the link. Keep pressing forward!

Hope all is going well in Sante Fe. Looks like I’ll be ordering your book set soon. Gave both of my copies away this past week to interested people. As always, waiting anxiously for the next chapter!

Semper Fi

Sorry about not getting back to the comment in time Jack. I’m getting better, or so I hope…

Semper fi,

Jim

Can smell it, feel it, taste it. Living in the Lowcountry I know the humidity. Superb writing. Can’t friggin’ wait for the next installment. Was telling my daughter’s friend who is a newly commissioned artillery officer in the Army from Clemson ROTC (Go Tigers!) about your appreciation for Army arty. I am buying the series for him. Love it!

Can’t thank you enough Grady, and for the compliments too…

Semper fi,

Jim

Hey Lt.great read. I was in the Valley after your tour. 1969 w/9th Marines This last entry has got me fidgeting, the hair standing up on my neck, goose pimples and knotted stomach. People need to know the real deal. Thank You

Doc D. G 2/9

My pleasure to respond to your comment John. Yes, I thought it was time too!!!

Thanks for the compliment evident in your writing.

Semper fi,

Jim

Like so many teenagers from the late 60s I too had friends that made the ultimate sacrifice in Vietnam. Thank you for helping those of us that did not have to go get a true picture of what it was like for those that went. I am certain that even the most descriptive writing at your hand cannot fully describe the horror and terror of it all. Thank you one and all veterans and active duty for your service!

Actually, in reviewing what I’ve done, I’ve, more or less, created a primer for those who might end up in full blown combat.

Only 375,000 of 2.7 million actually had that happen to them. Us. I mean. Thanks for the thanks and liking the work David.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was, was always, enthralled. Right up to the point those satchel charges went off, and then… Well, now I’m tremblin’ and my heart’s beatin’ a little fast! That was somethin’ else! Thank you, Mr. Strauss for tellin’ you’re story here. I really look forward to ownin’ a copy when it’s done.

Thanks Lance, it was indeed that kind of a time back there in that valley of mud, leeches and rolling human

misery…but every once and a while I clean it all up in my mind and it does not seem so out there.

Like Jurassic Park or some other fantasy!

Semper fi,

Jim

Supposed to be watching a movie with my wife right now, but couldn’t resist opening the new chapter when I saw your email. Without a doubt, this was the best chapter you have submitted. The descriptions were so vivid, so real, I felt like I could taste and smell it myself. Spot on. Sitting safely at a desk here reading it, I felt my own heart rate increasing as you moved forward in that awful dark valley, making a full frontal assault that very few warriors ever made and even fewer survived. Damn! And damn good writing, sir. Thanks again for sharing.

I have gotten that ‘best chapter’ compliment on so many segments and it now makes by smile broadly. I never know in the writing

what you guys and gals will think. Really. I must admit that what you think means so much to me and I would never have predicted that

when I began this rather different and strange writing odyssey. You make my heart soar like a butterfly, was an expression once written

to me by an African kid I’d helped out. You do. The kid got it right…

Semper fi,

Jim

Hey Lt. Have calmed down enough now to let you know that I think that I have had my lesson for the day. Belly has stopped quivering and my eyes have stopped blinking and watering. That’s about really. Have come to realize and understand a little more about the stories my father shared with me about his time in WW2 when I got home from Nam. Thank you Sir for the clarification. Take care..Wes

What a wonderful series of compliments written in your special way Wes. I much appreciate as I work on the next segment and go over

to the Eldorado Hotel in Santa Fe to get ready for whomever shows up. I have no clue. Strauss’s Army. What an unlikely out of place

name for such a bunch of rather wonderful outcasts….Thanks for having me as a part of your tribe and putting the importance on me and my

work that you do.

Semper fi

Jim

I don’t know how a description for such a bad situation could get any better or how your situation could get worse, but if the past chapters are any indication I am sure it will! For the last fifty years I have felt guilty for not being sent to Vietnam like my brother and brother-in-law were but reading here what it could have been like may have me re-thinking. Keep up the good work James,as i’m confident that you are helping others much more deserving.

So glad you were not there too Sherm. That way I do not have to commune with another soul that was ‘rubbed out’ before it truly came alive in life.

Thanks for the depth of the compliment I read in your writing. I can’t tell you how much your comment, and the others, mean to me…

Semper fi

Jim

Terrific writing James. I can feel the end coming faster than Cowboy’s Skyraider on finally approach to target area. I’ve followed you all the way with a few comments too. I for one don’t want this to end for your story carries me along as if I was in the current of the Bong Song not physically paddling with the flow. I was grunt Army in in out of the A Shau 68 – 69. Someone correct me if I’m wrong, but I remembered the NVA had 51 caliber along with 61 mm mortars. Being a mm or two larger they could use our Ammo but we couldn’t use their’s. In the A Shau we heard of three man 51 caliber machine gun teams manned by the larger Chinese soldiers. Talk about “pucker factor”. One of our sister companies ran into one of these teams. They got chewed up and lost men,and we didn’t want to run into a 51 caliber ourdelves. You’ve never lived until you felt fear in combat. Isn’t Courage being sacred but doing what needed to be done? Show me one who was never sacred over there, and I will you show you one who was never in real combat. It seems the greater the War story the further the individual was being the lines. I guess this was your time the right time to write your story— for all of us.

Paul H 1/327 101st, A co. June 68-69

Thanks Paul. When I started I had no clue I was writing for

‘all of us,’ as you put it. I thought it was just me. But then the guys like you started to write these comments and the work

changed and my life changed with it. What a grand feeling to know I was not just this young huge fuckup trying to survive in the

the loneliest shitty unit in the world. Thanks for the compliment and just how well written this comment is.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks again LT, great read. Were there with you. Alot of us went through something similar. First known kill is always remembered but we did what had to be done and continued with the mission. I still remember the look on his face and his eyes but I am alive, which is what he was trying to put a stop to. War is hell. Love the story and looking forward to the completed book. Keep it up LT.

Yes, Richard! I thought it was just me. And I hid the whole thing for so many years. I did not even tell a wonderful VA counselor the real truth.

How could I? He was not over there. How could he know or truly understand. But so many of the guys here were right there too. Not far away, either in

time or geography…and going through the same shit. What a relief to find that out. Now I can lay it all down and let the history books decide what real

war is like. I mean if these books make it into any history books! I don’t expect wild popularity in the real world. This real world is wonderfully fake

and I love it. To hold it all together takes strict belief in established and long-worn mythology. These works are not that.

Semper fi,

Jim

Yes indeed! What you said! The Phoenix rises!

Thanks for sharing your mind and spirit

Very Good Sir, as the rest have said TY. I was in a few fire fights but nothing like the frontal assault you write about. Makes me think of my training at Ft. Polk tigerland. I’m sure a real assault is way different. The fear and Adrenalin must have been off the scall. I mean a three man position dark of night on a lonely perimeter is bad enough, and the ambushes on both sides. But what you lived thru there is way over the top. Have a great experance in Santa Fe, I still work so hard to get away in the summer season for my work. Please tell us about it on Facebook.

Thanks Don, for the neat comment and wanting to be at the rendezvous.

It was terrific. The guys and gals who came were a wonder. Hope to see you next year.

Semper fi,

Jim

my god my god ! where do we find such men !

Thanks for that compliment Dusty…

Semper fi,

Jim

I was half deaf from the booming sounds of coming from just about everything! Fantastic chapter Lt! Thanks again!!

Thanks for the great compliment Rand. Writing early this morning in Santa Fe. What a neat place to do it. Glad to be back in

the world and meeting some of the guys tomorrow…or at least I hope. Maybe I’ll try to get a bit better organized next year!

Semper fi,

Jim

Another day of making life changing memories in the valley !!

As I recently told another Nam vet friend, I’m amazed at your recall ability Lt.!!

Keep the chapters coming as I can’t wait to see what happens next.

Thanks for telling the story.

SEMPER Fi

You are most welcome Sgt! I am glad that I am making an impression. Glad people like you are writing in

to reflect on it too. Means everything to this effort…in Santa Fe getting ready for the small group that might show up.

Spent a good deal of money and hope I do not have to invite all the street people in to eat it. Well, maybe the street people

wouldn’t be so bad at all!!!!

Semper fi, and many thanks!

Jim

Enjoy the meet & greet at Santa Fe, wish I could make it but perhaps next time.

Will look forward to it next year. Was a great trip.

Semper fi,

Jim

“There would have been no possibility of the small but heavy armored vehicle cutting through or crushing”

Might i suggest “heavily” instead of “heavy”?

Thanks Mike, got the correction in hand…

Semper fi,

Jim

It is wonderful to read about the struggles to stay alive we all went through , especially by someone who was there and experienced the same as we did . You really write in a upfront and reviling manner , that prevents the reader from putting the book down until the read is completed . Always impatiently awaiting the next chapter from an amazing author !!

Thanks Don, nice to read your comment as I am on my way to Santa Fe to meet with whomever shows up there.

So good to have ‘war buddies’ I never felt I had because I did not understand my own situation or theirs.

Funny what writing the books has created and how it has changed my life and some others too.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another compelling chapter. Thank God for Cowboy!

Supporting fires meant so much and some, like the chopper pilots and Gunny were simply devastatingly heroic and so well done.

Unsung heroic. Like so many. Come home and be quiet. There were so few witnesses and so many of those ‘crossed over’ in that

horrid beautiful valley…

Semper fi,

Jim

Each marine was equidistant. Equally distant maybe what you meant sir.

Thanks for the help Mike. Hard to edit without that kind of support.

My guys and gals!

Semper fi,

Jim

I could almost smell the jungle crap that you dragged us through. Great segment! Chuck

Thanks Chuck, yes it was something else again and, in the rest of my life, never experienced

anything life it and I have been all over the planet.

Semper fi,

Jim

I am sitting in the middle of the Fingerlakes National Forest …. Alone. 68 and I was 18 again for the whole read. We had no ontos, no Sky raiders but we had Huey gunships, phantoms and the Jersey fired for us at the base of 522 November 5th and 6th 1968.

Your words transfixed me there, with you …vividly …. I could taste it again, hear it, see it, smellit and most definitely FELT it!

Well done, SIR! You can call the river the Bong Song all you want. Semper Fi … from an old Airborne HERD Bro.

Laughing at the Bong Song comment. We sure as hell didn’t get everything right over there or truly understand

our own situation. Day to day and night to night….just trying to get by. And be whatever we could scrape together of

the Marines we so wanted to be and get back home.

Semper fi,

Jim

Not in my considerable time spent reading published diaries of the human condition in a stressful environment have I felt that I was there with the author when the events occurred. This is true with all three 30 day books. Your writing is extraordinary but then you are as well. Thank you for telling your story, it magnifies your combat brothers as well revealing their experiences.

Thanks David. I am unsure how the transfer is made, of taking myself and other vets back…but I got there too when I am writing away.

No real reference materials. Just the stuff that went down. My wife asked me what was coming next yesterdays so I told her.

She said “don’t do that again,” because she wants to read it instead of hear it. Like the books are somehow different. Strange but true.

Like I am her husband right with her but the story is about someone else. I guess I was someone else back then.

Semper fi,

Jim

You know from time to time I’ve been able to send edits after reading, but honest to God this was so tense and fast moving I don’t think I’d have the courage to offer up any edits even if I had spotted one. How did you put this detailed a plan together on the fly. Surely a mark of a true leader. Thank you and your fellow Marines for your service.

You are the last person I might think lacked courage. You are a man among men. But I get the intent of your comment and the depth of your

compliment. Thanks so much Bob. I never felt like a ‘true leader’ as you can pick up from the writing. Without the Gunny, and the guys and Cowboy

and so many others I was just a bit more than one of those leeches under my blouse…

Semper fi,

Jim

August 1970, in the The Valley under heavy assault and fire Sgt 1st Class “Pappy” Johnson Strike Force 101st Airborne stood up and said,” get up an on line an charge, take it to the bastards an I will shoot the first MF that breaks or runs.” And we did.

Thanks for the great tough comment Jim. I wasn’t that tough although I wanted to be. Still want to be! Still not!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

Realy great writing JAMES !!!!

Thanks Harold. I read your name as “Harold Heaven,” and that made me smile when I went back. Great compliment Mr. Heaven and I really appreciate you

writing it on here for all the guys and gals…

Semper fi,

Jim

Great chapter one really gets the feeling of being there with you and going through the stress of the battle. god bless you guys that went through that war

Jim t

My intent is to get it all down and I have no idea until I come on here and read the comments how I did.

I guess this last one was pretty good. Sometimes the nearly never-ending action is easier to write about than the character asides between

bouts of combat. Thanks for the compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

May sound a bit strange, but as I was reading those last few paragraphs I could hear Frank Sinatra singing a stanza from “I did it my way,” Yes, there were times, I’m sure you knew

When I bit off more than I could chew

But through it all, when there was doubt

I ate it up and spit it out

I faced it all and I stood tall

And did it my way.

Thank you, and all our armed forces for your service. God bless.

Mostly I did it their way and the Gunny’s way. At least that is how I felt. Being one with a Marine outfit was

an acquired taste and it was a whole lot more participative than it was in getting the Marines to do what I thought they ought to do.

I came home with such an appreciation for enlisted and ‘common’ men and I still hang with ‘common’ men whenever I can not matter where I am.

Give me a plumber, waiter, construction guy or gal over a stock broker or highly educated person anytime. Real life.

Semper fi,

Jim

Amen and Semper Fi!

Thanks so much for the morning compliment, as I continue the work T.E.

Means a lot.

Semper fi,

Jim

Excellent writing LT please keep up the great work sir.

Semper Fi

Thanks Lee for the great compliment and putting it up on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another great Page in your life, really appreciate these chapters. I was discharged before all the troops were in Vietnam. All they were doing at that time was sending us in as advisors. Would have beeen proud to have been your Radio operator as that was my jpb in 2-3-3 com. I don’t understand your feeling badly about being afraid, because if you weren’t at all I would think you were nuts, thanks again for telling it like it was.

Funny about feeling bad about being afraid. I think it is probably genetic in us all. It is also a response to mythology we are taught.

You don’t see any super heroes feeling bad about not being courageous. Flash Gordon was never afraid that we got to see. And so on.

We are not ready for it, especially those of us who went through Marine Officer training!

Semper fi, and thanks for this comment in depth…

Jim

Finished with a bang Jim. Thank you!

Yes, it is that kind of time and its developing down in that mess of a valley.

Semper fi, and thanks for sticking along with me.

Jim

DAMN,

Dante’s vision of hell is not this terrifying.

True. Dante didn’t really live it though. He thought it up and imagined it. The Marine Corps didn’t mean to send me into it either. They just didn’t know

it was like that because so few reported back and then they couldn’t really report….just stand there and stare, so ecstatic to survive and be alive

that silence was their only communication tool.

Semper fi and thanks Rob.

Jim

WOW! Kick Ass Marines and COWBOY!

Sometimes we got it right and where would we have been without that ancient giant old pterodactyl of an airplane? Not to mention the

gutty brilliant pilot who flew it.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, I wasn’t a ground pounder. I drove a wrecker different fire-base every 2-3 days unloading supplies changing out gun tubes and packs for the Gun-Bunnies. Loved them. Took heat several times during convoy and endured several infiltration’s and the joys of traveling into Cambodia May June 70. Your writing brings up lots of memories and emotions, as it should. I am honored to know You and Your men if only through your writing. God Bless You keep up the good work !!!! Might I ask the outcome for Gunny and Nguyn

I cannot comment on the outcome of events until the outcome of events…so keep on reading. All mysteries will be resolved in the end.

And then there wlll be the book about coming home, for those that care about how that was. Thanks for asking and the compliments and your own

supporting service…

Semper fi,

Jim

This is the first chapter I have read, and it was riveting. Even though I have not read what came before, I could still read this as a complete unit in itself. I will try to do some catch-up on the rest. Strangely my attention was held through the whole chapter even though this would not be a genre I would normally choose to read. I don’t particularly like war movies, either. But this is well-written and very descriptive. You show rather than tell, and that is good. I found myself picturing scenes in my mind though I have no idea what the area looked like. I had envisioned the firing coming from your left even before I got to the part where you revealed this fact. Good work.

Thanks so sincerely Diane. There are not that many women who read the work, although I hope there will be more so they can better undrstand

the guys who made it and came home. I think it helps to know something of what they went through and the truth is hard to tell for almost all of them.

Semper fi,

Jim

Really good stuff especially your reaction to that first man to man kill up close and personal. For many it is the stuff that nightmares are made of weeks and years later. God bless and keep you well

Yes, those looks do not go away, ever. The looks of ‘how could you do that to me?’ and more.

Thanks for appreciating that and for putting it up here.

Semper fi,

Jim

LT, right now I want a warm shower to remove all that mud you just took us thru ! Best yet, Thanks.

Yes! I just too one, again! I love showers and take them all the time…and still check myself for leeches! Maybe I should not have

written that. The comments on here draw so much out of all of us…and I think that’s good too.

Semper fi,

Jim

I found myself staring at my IPad after reading this! Then I realized I was reliving a particular firefight, adrenaline and all sensory things at full crank! Great to be alive isn’t it? Semper Fi!

Yes, Tom. It is great to be alive, no matter what the circumstance. I was once in a hellhole prison in Africa and on the yard.

It was a rotten place but I was standing there looking around and smiling. A guard came by and said “what the hell are you smiling about?” I could

not explain. The yard, the prisoners, the food, the sky, the sun and all of it…and I was not in the A Shau Valley fighting for my life and losing

all my Marines around me. Smile. No way to explain that.

Semper fi,

Jim

he Gunny ran forward, his own sidearm out, flocked with a small group of Marines surrounding he and his radio operator closely before they almost magically splitting away to blend individually into the bush.

surrounding HIM and his radio operator …before almost magically splitting away, (drop the “they”)

Thanks for the help Michael. I will get to it as soon as I finish the hundreds of comments on this segment. Comment response comes first.

Semper fi,

Jim

In the first paragraph you mention there was no vegetation tall enough to hide in, but in the third paragraph you talk about the thick jungle growth hindering the Ontos. Confusing but the frightening chaos of the description grabs the reader more! What a read……

Yes, the variations in flora were simply astounding as we moved through and into different parts of the jungle. Not like Tarzan or what I was led to believe.

Thanks for pointing out that I’m not always spot on accurate in recall either!

Semper fi,

Jim

This chapter made the hair on the back of my neck stand up. Thank you for your story, James.

Thanks for that great compliment Ed!!!

semper fi,

Jim

Yes very exciting.Wow is all I can say..

Thanks for saying that right here and now Jim. Helps me along…

Semper fi,

Jim

Wow! You have it all Lt. Some chapters are deeply introspective and some are just action packed like this one. No matter what though, this work you do will live on for a very long time and is having, and will continue to have, a very deep impact on many people. All the best.

Thanks e. I had no idea when I started. Now, the work has a life all of its own, and its mostly a work carried by you guys and gals…

No author could wish for better comments.

Semper fi,

Jim

Outstanding.

One word compliment that is so Marine Corps. Says it all…

Semper fi,

Jim

Once again LT, you have taken us into the depths of hell, willingly, and without anything more than our wits to keep us going. You, sir, are by definition, a leader of men. My only regret is that I did not have the honor of serving with you during my time in the Suck.

I am so glad that so many did not serve with me in the Suck. The mortality was so very high. You are here with me now and I much appreciate that.

Thanks for the compliment and that being here with men now.

Semper fi,

Jim

Kicking and screaming on the inside. You consciously stop breathing, your gut tightens and your body and mind react just like they were trained to do. You are amazed at what you and your team accomplish. It’s kill or be killed time, and it’s good to be advancing, until it’s not.

Thanks, you bring it back!

Yes, Parker, that is a perfect description of what it was like! You had to be there to write that.

uuuuuurah, brother.

Semper fi,

Jim

Very,very good. Your ability to pull the reader in is a talent that serves all of us so well.thank you for your service and thank you for sharing

Thanks Eric, much appreciate the comment and the compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Your story will echo down the corridors of history. It should be required reading at OCS and all of the service academies.

I don’t think the reading at those places will ever happen, unless the work is bootlegged in.

Those training establishments survive on the mythology. There’s little myth to carry you along in real combat.

There’s truth out there in those deserts and down in the mud. Hard killing and punishing truth.

Surviving and learning it and then coming home is to be diagnosed with PTSD…or worse.

Semper fi,

Jim

The latest chapter came up on FB first, BUT I need a quiet place to read. It was worth the few hours wait. I don’t know anything going on around me as I read and probably a few minutes afterwards.

What a remarkable compliment Bob. Thanks and I cannot tell you how much such original soul displaying words carry me on through as I travel this

unexpected journey of getting it all down.

Semper fi, and thank you so much.

Jim

It is hard to top your previous chapters James but this one leaves the rest in it’s dust. Thank God for Cowboy and for Gunny planting the attack seed in your mind. I won’t be making it to Santa Fe but once you get back we need to get together for lunch or something.

I will stand by to receive you or meet you wherever I can. The guys. The real guys. I met one on a motorcycle yesterday. He was getting fuel in front of me and wore a

Marine jacket. Al. Nice guy on a Harley. I gave him my book. He said he’d read it right away. I wonder if he will. I asked him his unit over there and when he served.

He was from my battalion and at the same time. For some reason I stopped and did not tell him about me or my time. It was such a lovely sunny day at that Love’s truck stop.

It stayed that way. He drove off. I wonder if he will read the first book. I wonder if he will comment. I wonder if I could not have handled the meeting better. We are all such lonely creatures traveling the road of life on

our Harley Davidson chariots…

Semper fi,

Jim

I have a question born from not having been there…

If the surface was so muddy and saturated, how did the tunnels avoid being flooded all the time? In a river bottom I would assume a pretty high water table…

Amazingly, the water table was not that effected by the surface water. The kind of mud and rock, apparently, kept the deeper soil dry. I don’t know how but it was

true. Anything that had a channel down to it or was exposed though filled up with water pretty fast.

Semper fi,

Jim

The availability of the next installment came up on the Pad at the same time my partner of 58 years said breakfast was ready. Then a twinge of guilt grabbed me because your first words brought back the memory of what the Company’s movement was this particular hellish morning. Me, warm food, and hot coffee, you no food and no water except what splattered on your face while running into Hell, and in a frontal assault on trenches and tunnels. The effect of powerful words telling a powerful story. Good show, Sir. So sorry to miss this second opportunity to meet you and men of the same grit in New Mexico. Have a glorious rip snortin laugh for the whole trip. All of you have earned the time to decompress in the presence of each other. God Bless

Would love to meet you one day Poppa. I am so happy for the dissonance of the joy and coffee and mornings and all back here as opposed to that shit.

The wonder of life and the pleasure of living it in the USA!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, your ability to put into words the hell that was that place has me smelling, tasting and feeling it again. Well done. Keep it coming.

I am writing away Bill, and highly motivated by your complimentary words…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim

Thanks for the one word comment Dr. Phil, but I’m not sure what you meant by the word!

Semper fi,

Jim

What they said. You have become a masterful genius.

That read sent my blood pressure clear up into the normal range. Well done Lt.

Thanks for the compliment and the way your fashioned it Tom.

Semper fi,

Jim

Gave me chills reliving that with you. Some how I can still smell the mud and crud.

Thanks Don, much appreciate this comment…

Semper fi,

Jim

The “Sunken Stage” description was perfect. Amazing how one could almost feel somewhat detached and able to watch from different perspectives. So true !!!

Thanks Mike, it just comes out, in perspective, it is true. I was there and living it but my rendition

is indeed only a perspective through all these years.

Semper fi,

Jim

The sound and the fury. My training didn’t prepare me for the deafening sound, the taste and smell of the cordite and gunpowder. You had me right there with you Jim, again! Another great chapter. Hope Zippo survived. I really regret not being able to attend the gathering. I will be there in spirit and I know it’ll be memorable! Semper Fi James!

Missed you at the rendezvous Jack. Would have been fun to hang out.

Thanks for the kind words…

Semper fi,

Jim

I look forward to every chapter, and enjoy every word! thanks for telling us about your experience.

Thanks for the compliment written in your comment William.

Semper fi,

Jim

Fuckin A LT!

Thats a bout the best compliment you can get in the Corps. And Gus Grissom, of course. Loved that man, and the corps too..

Semper fi,

JIm

I feel like I am there with you every step of the way. I can’t believe the sensation inside of me as I read this. Thanks Jim

Thanks for the compliment and I want you to know that words like that keep me going…

Semper fi,

Jim

LT: GREAT job!!!

A couple of minor changes:

1) Paragraph 3 “The Ontos had stopped to reload 106 rounds.” Should read “The Ontos had stopped to reload 106mm rounds.”

2) This paragraph: “The Ontos stopped its forward progress, and the two heavy armored doors on the rear of it sprang open. The Gunny jumped out and loped toward me. I noted that he didn’t carry an M-16 either or anything but his sidearm either, and he had no pack on his back.”

You used the word “either” twice in the last sentence. Delete one of them.

Hooah!!!

Thanks a ton for the help Craig, and we are not it…

Semper fi,

Jim

Another good one

Thanks David, means a lot to hear from you.

Semper fi,

Jim

Criminy! That’s intense stuff and we are getting monsoon type rainfall as I read this. I need a smoke!

(And I don’t smoke anymore)

Thanks Laddie! And I get that smoke feeling every once and awhile myself!

semper fi and thanks for the compliment…

Jim

I have never read and followed a more exciting adventure than yours. Thank you.

Thanks Ed, that kind of deep compliment has a lot of meaning for me…

Semper fi,

Jim

The combat seamed like hours but I know was only minutes, now to get my hart rate back down.

I will thinking of all of you guy in Santa Fe, have a good one.

Yes, it seemed like hours when I was in it too! thanks for the comment and support Mike…

Semper fi,

Jim

So glad for the privilege to read this. Thank you for your service and for sharing.

I am so happy you consider the reading a privilege Chris. Means a lot to get your thanks too…

Semper fi,

Jim

Another excellent chapter. Pulse was starting to increase the more I read. One of the best ones yet.

Great compliment Chuck and I thank you most sincerely,

Semper fi,

Jim

Respect, Sir!

Right back at you Bruce!

Semper fi,

Jim

Tha sound and the fury. The training we had didn’t prepare you for the smell, the noise beyond deafening, and breathing the debris in the air. You had me right there with you Jim. Another great read! I’ll be with you guys in spirit, plans just couldn’t be changed! I’m sure it will be memorable! Semper Fi!

Thanks for the usual great compliment from you Jack. Means a lot to me, as you know…

Semper fi,

Jim

Man talk about reading fast !

I ran a few patrols but never anything like this .

Now I know….

Thanks for the read and the support in writing on here Beau. Much appreciate…

Semper fi,

Jim

Great chapter, Jim!

Thanks for the compliment Buck…

Semper fi,

Jim

I need a favor, could you slip in “it’s a book” ocassionally so I don’t crouch down and look for cover? It looks odd at the breakfast bar in my kitchen. I will have you and your Marines in mind Wednesday morning, maybe wear the t-shirt.

You are the best Walt KcKinley. And I much enjoy reading your comments on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

This may well be the best yet. Thanks again. . .to all of you.

I like that comment, the ‘best yet’ as I have had it written on here so many times.

What a grand compliment whenever it pops up.

Thanks so much Robert.

Semper fi,

Jim

WOW and following step by step down the valley.

Thanks for the follow and the compliment of your following Ron!

Semper fi,

Jim

your writing gets so intense at times I have to reread some parts because they drag me back into my own memories and I only see your words while my mind is back fifty years !

That’s a great compliment, really, William. I am so happy and sorry!

Much appreciate you writing about it on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

THAT’S HOW I REMEMBER combat in I CORPS..CONTROLLED chaos under triple canopy at times..rain..the sound of a 12.7 machine gun at your position at times and an elusive but well trained NVA who thought the A Shau Valley was safe for them

.until they met the 9th Marines..Semper Fi

Yes, you have put your finger right on it Tony. Much appreciate the comment and support written into it.

Semper fi,

Jim

Pulling me back by my right arm. missing arm. I am waiting for the next episode. Thank you for the great job of telling us the story. I have used the Claymores many times in the wire. They are awesome.

I am sorry about your arm Don. My scars were bad but at least I kept all the parts…mostly working.

Thanks for writing on here and sharing what you think.

Semper fi,

Jim

The fog of war. Utter confusion yet you press on. What an incredible group of men! Hey, maybe Cowboy became a crop duster after he retired.

Some minor editing suggestions follow:

I watched the dawn bring evermore light through the misting

While “evermore” is a valid word I’m thinking maybe “ever more” is closer to the meaning you wish to convey.

Trying to get Marines in training to stay out of clumps, or naturally congregate together, had proven impossible for training officers.

Maybe a bit smoother to say something like:

Trying to get Marines in training to stay out of clumps (as they naturally congregated together) had proven impossible for training officers.

OR

Trying to get Marines in training to stay out of clumps, or not congregate together, had proven impossible for training officers.

bombs were pickling off the plane’s wings

I can’t find a meaning for “pickling” that fits the context.

Maybe: bombs were peeling off the plane’s wings

The whirling Wright engine of Skyraider quieted as it gained distance

Maybe add “the” before Skyraider

The whirling Wright engine of the Skyraider quieted as it gained distance

and that meant recognition problems about whether the personnel was NVA or Marines.

Maybe substitute “were” for “was.”

and that meant recognition problems about whether the personnel were NVA or Marines.

The sound of the AK was very distinctive and the NVA didn’t use tracers in their submachine guns.

Are you identifying the AK as a submachine gun or is some other weapon a NVA submachine gun?

Definitely seen green tracer from AK-47s.

The Gunny ran forward, his own sidearm out, flocked with a small group of Marines surrounding he and his radio operator closely before they almost magically splitting away to blend individually into the bush.

Maybe “surrounding him”

Maybe “split” rather than “splitting”

The Gunny ran forward, his own sidearm out, flocked with a small group of Marines surrounding him and his radio operator closely before they almost magically split away to blend individually into the bush.

OR keep “splitting” and drop “they almost”

The Gunny ran forward, his own sidearm out, flocked with a small group of Marines surrounding him and his radio operator closely before magically splitting away to blend individually into the bush.

I felt like moving through a sunken stage

Maybe add “I was”

I felt like I was moving through a sunken stage

I was half deaf from the booming sounds of coming from just about everything

Maybe drop “of”

I was half deaf from the booming sounds coming from just about everything

seeming to slip through a crack in the reeds and tall elephant grass that couldn’t have been there.

I’m not sure of the intended meaning. Maybe “shouldn’t” instead of “couldn’t”

seeming to slip through a crack in the reeds and tall elephant grass that shouldn’t have been there.

He’d grabbed the sleeve of my right just back from my elbow and would not let go.

Maybe add “arm” after “right.”

He’d grabbed the sleeve of my right arm just back from my elbow and would not let go.

*************

Travel Well, Travel Safe to Santa Fe. May brothers in arms come together to share what cannot be spoken, only felt. May any spouses who attend understand that strong emotions – both positive or painful – may surface. If so, just be easy. He may not be able to explain.

*************

The Wall That Heals aka The Traveling Wall will be in SE Iowa at the Fairgrounds in Fairfield. Arrival will be late Tues afternoon Sept 11th. Visitation is from Thurs the 13th through Sun the 16th (maybe ’til noon). I’m guessing assembly will be on the 12th. I’ll be standing vigil Friday midnight to 4 AM Sat. I’ve heard that’s when those who need to grieve alone come.

James, I know you have stated you cannot visit the Wall. If something changes in Santa Fe, this location should just be a short jog off your route.

To All; Blessings & Be Well

Thanks so much Dan. Means so much to have this kind of help in editing. We are all over it…

And thanks so much for the invite. I will get back to the wall in time…and the traveling wall sounds so much

more personal and better.

Semper fi,

Jim

I really enjoyed this chapter, excellent work.

Thanks Alex, for the compliment…

Semper fi,

Jim

On the edge of my seat again LT. Can’t wait for the next chapter.

Thanks for the great compliment Robert…

Semper fi,

Jim

If I had been a grunt down in the muck, I would have wanted you for my leader. Your savvy of the situation has been uncanny. Well done!

Thanks for that great personal compliment Dave. I tried my heart out, that’s for sure, once I got around to figuring things out a bit…

Semper fi,

Jim

Great read once again James…action packed…you do know how to plop us right there in the mud with you…Wish you much success and communion in Santa Fe…

Thanks Mark, sorry to have missed you in Santa fe. Thanks for the compliment too…

Semper fi,

Jim

Another amazing chapter Sir!

Thanks Jerry for the sincere compliment…

Semper fi,

Jim

Do not think I could have handled it. Hooray for y’all heroes!!!

I bet you would have surprised yourself if you had been there, but then you might be on here to write, either…

Thanks for the apropos compliment and comment…

Semper fi,

Jim

9:30 pm surprise. Read it twice back to back.

Cant get over the reality of what you and your company endured for weeks on end. Great story and already looking for the next part. Thank you.

thanks for the compliment written into this comment Vern. Reading it twice and in the morning. Wow…

Semper fi,

Jim

Composite B and the Claymores…with the Gunny setting up the chain of command for gettin the job done, “efficiently”! Mothers and beans, Lt! Thanks so much for sharing this ration of your reality! Especially sir, for that ten second glimpse into a dead man’s eyes, which speaks only to the unspoken truth you and and all your combat brothers in arms would have to face at some level, ever after. Thank you for your service Jim… Semper Fi

ddh

thanks Dennis and I much appreciate all that you write on here….

Semper fi,

Jim

The closest I’ll ever be to mortal combat is in the pages of a book. I’ve read scores of very good books by talented and experienced authors. There is a similarity of description in all of the “good ones”. They sound a lot like this: “Being in the center of the combat I felt like moving through a sunken stage where just around and above me, all different symphonies of raucous music played. It was as exhilarating as it was frightening. I was half blind from the flashing of muzzles, explosives, and particulate in the air. I was half deaf from the booming sounds of coming from just about everything, but I was also moving, thinking and not running away.” In your own self-deprecating way you try not to portray any courage or particular battle skill set to yourself. You let us know that Marines are brave, but are warriors mainly because they have found that that is the best way to survive. Both you, and your raggedy assed Marines, had what it takes when the time came. I hope you and those of them still around can give that little nod of the head in acceptance of that accomplishment, and our appreciation of it.

Semper Fi,

John Conway

Hard to read that comment without giving it real serious consideration John.

You have that talent in your own writing.

Straight at me and no avoiding it.

Thanks for excerpting the quote and brining it more to life.

I re-read it and wondered for a moment if I wrote it!

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

I am reading “Hue 1968” and it is dry reading compared to you, Jim.

Bowden did write an informative side note on the history of the Ontos, and how the army rejected them. The Marines put them to good use in Hue.

Rivron 15 ‘68-‘69

Thank you Brad. My story is not a recitation of accepted history, no matter how arcane.

My story is an odyssey through the real fields of combat and what really goes on inside the beast of battle.

I wrote it because I never found any book that directly dealt with it like I found it to be.

Hue follows much of the mythology of war that remains the version most people will believe.

My books detail the road less traveled.

Semper fi,

Jim