Ajinomoto

To be stuck in Hawaii without any money was a horrible thing for any kid, particularly three white Haole kids, coming from a military family and living in a downtown local area on the fringe of downtown Waikiki. Kapuhulu was what the district was called. I lived there with my brother and sister because the rent was  cheap and it was close to St. Augustine Catholic Elementary just down the hill where the three of us attended. It was also very close to where my mom worked at Lewis of Hollywood, a hair styling salon located just inside the lobby of the Moana Hotel. Dad was gone to sea, so we four had to take care of ourselves. Mom worked all the time so that left just us three. When dad had gone out to sea a couple of months ago, not to return for many more, our weekly allowance had gone with him.

cheap and it was close to St. Augustine Catholic Elementary just down the hill where the three of us attended. It was also very close to where my mom worked at Lewis of Hollywood, a hair styling salon located just inside the lobby of the Moana Hotel. Dad was gone to sea, so we four had to take care of ourselves. Mom worked all the time so that left just us three. When dad had gone out to sea a couple of months ago, not to return for many more, our weekly allowance had gone with him.

On our own for the summer months proved unbearable because we had no money. Not even change to spend on Green River drinks, Bubble Up or for bus fare or games at summer fun in the park. Living in a local area meant that we couldn’t tell the other kids that we were broke either, or more derision and laughter would have come our way.

We roller skated a lot. All three of us received clamp on roller skates the Christmas before. My brother was twelve, I was eleven and our little sister was nine. At those ages skates were a big deal even if they spent two-thirds of the time being laboriously clamped back on all the time. We were rough kids, the concrete and  asphalt we skated on was rough stuff and our frequent tumbling falls were even rougher. We lived on Kamuela Avenue, which was a little one block street that connected Date Street to Kapahulu Avenue. Hunter picked up across Kapahulu to allow the intersection to be four way. On each corner of that intersection back in the fifties, was located a Chinese restaurant. Won Ton Corner, was what every called the confluence of Chinese restaurants. The neighborhood was almost as Chinese as it was of local descent. Even the theater we went to see Flash Gordon every Saturday morning was Chinese owned and run, which meant that everyone was loud but the rules were strictly enforced.

asphalt we skated on was rough stuff and our frequent tumbling falls were even rougher. We lived on Kamuela Avenue, which was a little one block street that connected Date Street to Kapahulu Avenue. Hunter picked up across Kapahulu to allow the intersection to be four way. On each corner of that intersection back in the fifties, was located a Chinese restaurant. Won Ton Corner, was what every called the confluence of Chinese restaurants. The neighborhood was almost as Chinese as it was of local descent. Even the theater we went to see Flash Gordon every Saturday morning was Chinese owned and run, which meant that everyone was loud but the rules were strictly enforced.

Just up Kapahulu Avenue there was a bakery. Every Saturday morning the three of us would walk there, not strapping our skates on until we got to the big bare parking lot behind the bakery. The skates would not stay on to cross streets or jump curbs. By the time we got there later in the morning the bakery trucks were out on delivery, the bakery was serving broken cookies at the back door in little white bags for free, and the movies didn’t start at the Chinese theater until noon. Since we never had three dimes to get into the theater we had to wait until the shows were running before our friends could slip us in through the fire exits.

One Sunday morning we showed up and sat near the back entrance, consuming our bags of broken cookies and getting our skates on when an old Chinese man walked up and sat against the wall with us. Before we could figure out what he was doing there he started to speak.

“You kids know how to swim?” he asked, out of the blue.

We looked at one another but didn’t respond.

“Come on, three Haole kids as old as you can certainly swim,” he said, as if talking to himself. “Well, maybe you can’t,” he finished, after a moment.

“We can swim,” my brother Mike said,” not about to be put down by some old Chinaman.

“Thought so,” the old man said, with a gentle laugh. “How about bikes? You got bicycles?”

“My brother and I do,” I blurted out. My sister Susan was promised one but not until she reached ten years of age.

“Now, here’s the question,” the man said, without going on.

We waited, looking at one another again. Finally, my brother couldn’t wait anymore.

“What’s the question?” he asked.

“Thought you’d never ask,” the strange man responded. “Do you want to make some money? Cash money. Just for having fun?” At that point he took out a new dollar bill and held it out in his hand. The dollar flapped gently in the trade winds.

“Okay, what do you want?” Mike asked, the tone of his voice revealing that his patience with the old Chinaman was growing thin.

“You know Keehi Lagoon, off Hickam shoreline?” the man replied.

“On the base? That lagoon?” Mike answered.

“Yes, that’s the one. You kids are service brats, if I’m not mistaken. You can get on the base with no problem.”

“We’re not spies,” my brother said.

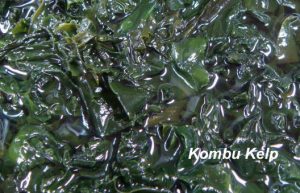

The old man laughed. “No, nothing like that. Just outside the reef at Keehi Lagoon there is the only place in the islands that Kombu sea weed grows. It’s down about forty feet off the outside of the reef there, just off the island. If you dive there and get some seaweed I’ll pay you a dollar a pound for everything you can bring back by late next Saturday afternoon. But you have to get down there and get in the morning of the same day. Old sea weed’s no good.”

“How would we get it back here?” my brother asked. “That’s almost ten miles.”

“Bike,” the man said. “Tie a wagon to the back of your bike and pull it back. It’s not a hard ride if you do it early on Saturday morning.”

I watched my brother think for awhile, finishing his cookies. “We don’t have a wagon,” he finally said.

“That’s easy,” the old Chinaman replied. “I’ll have a wagon here earlier than you can get here, with some rope. A wagonful of Kombu might make you five bucks at one time.”

“What’s Kombu look like? How will we find it when we dive down?” Mike asked.

“What’s Kombu look like? How will we find it when we dive down?” Mike asked.

“It’s black,” the man said. “Sticks up about two feet like waving fans. You can’t miss it. The patch is in the middle of a whole bottom filled with the white stuff. You’ll see if when you go down. It comes up easy if you just pull on it. Try not to pull up the root and then it’ll always be there to give more.”

“I have to talk to my brother and sister,” Mike told the man. I thought he just wanted the man to go away so we could skate because my brother never talked to my sister and I unless it was to tell us to do something or yell about something we’d done.

“Okay. I’ll have the wagon here and you can have it even if you don’t want to go get the stuff. I won’t be here but I’ll be waiting Saturday afternoon.” The old man got up, dusted himself off, smiled at the three of us and walked away. In seconds he was gone.

“What do we do,” my brother said, stunning my sister and I both. Neither of us said anything.

“If we pedal down there with his wagon we can do it in less than an hour but it’ll take longer to get back coming up hill and with more traffic. We only have Dad’s old UDT goggles, one pair.”

“What if we do all that and there’s nothing, and how do I get there? my sister asked.

“Ride double on Jim’s bike,” my brother answered offhand, “I’m not riding you anywhere, and I know the stuff is there, if that’s what it is. I’ve been down there diving with dad.” Mike was the only one of us dad would take out on anything serious

“You can haul the inner tube,” I said, my brain working furiously, already spending my share of the five bucks. “She can wait with the bikes to make sure we don’t get ripped off. We can float the tube out over the patch and take turns using dad’s mask bringing the stuff up. Forty feet’s pretty deep.”

“It’s nothing,” my brother replied. “Okay, let’s see if he brings the wagon. I don’t think we should take her. She’s too young to guard the bikes.”

“She’s the fastest runner in school, even faster than you and me,” I answered, as if running fast was important. Apparently, however, it was.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s skate.”

We skated for hours, collected our stuff, stashed it at home and made it to the theater for Flash Gordon.

Ala Wai Canal, 1960

The wagon was there, along with a good piece of rope. It was six-thirty in the morning, not long after dawn. None of us had wanted to get up but wanted the money too badly to sleep in. My sister and I were mortally afraid that Mike would take it all but we were even more afraid to mention it. With the wagon tied to Mike’s bike we set out. The long ride down the hill to Waikiki was fast and easy. We coasted all the way down Monserrat and then peddled lightly along the Ali Wai Canal until it ended and we were on Ala Moana Boulevard. From there it was a curving straight shot to the base and lagoon drive. The trip took all of an hour.

When we got to the base the Marines just let us go through. Military brats over run every military base.

Mike said he knew just where to go and after several more minutes of peddling, the wagon making a big racket on the gravel and my sister complaining bout the dust and her sore bottom from riding on the bar, we arrived at a pocket area of the lagoon.

“It’s low tide, so be careful of the coral,” my brother warned. “We have to walk on some to get far enough out to swim. Since my brother never seemed to care a whit about my sister or myself I took his warning very seriously. Our feet were used to running around all year without shoes but Hawaiian coral was razor sharp. My sister was left with the bikes, as planned. There was nobody visible anywhere so security didn’t seem to be a problem.

My brother and I used the inner tube to float part way over the reef before reaching the deeper green water beyond. Larger waves lapped at us but nothing too big. Mike put on the googles and took a test dive. He was back in seconds.

“I didn’t remember it being so deep. I can see the patch down there but I bet it’s about a hundred feet.”

“Oh,” was all I could think to say. We dived off shore in Waikiki, Rabbit Island and even out at Kaena Point. I’d never considered depth. We just dived down to the bottom wherever we were, my dad, my brother and I.

“Okay,” Mike said, adjusting the big heavy mask. “I’m going down for a load. Then he was gone.

“I waited, bobbing up and down with the inner tube. I’d tied string back and forth across the hole when we’d arrived at the lagoon so whatever we got would not slip right through. All seaweed was slippery.

It seemed like many minutes before my brother reappeared. He lunged for the inner tube and dumped a big armload of awful looking black seaweed atop the tube. “Your turn, “he whispered, his breath coming in gasps. “Couple more loads ought to do it. Breath in and out deeply before you dive or you’ll never make it all the way down.”

I put dad’s mask on and followed my brother’s instructions. I could stay underwater four times back and forth in the school pool. I was good in the water. I dived. The world silenced and right away I saw the patch. For the first time, stroking downward strongly using the frog kick, I wondered how the old Chinaman knew about the patch and what it was. I reached the bottom, popping my ears three times on the way down. I knew I didn’t have a lot of time. I pulled on the seaweed with both hands. Fortunately, the stuff came away easily. I gathered a bunch under my left arm and then vaulted off the bottom upward stroking with my right arm.

“Wow, that’s a load,” my brother remarked. I’d brought up so much we had to make a run back across the reef to load the wagon.

“Who’s going to weigh it?” I asked, concerned about our cargo, as we paddle back over the sharp coral, going slowly in order to minimize the risk of getting cut.

“What’s he going to weigh it with and is it going to be weighed wet or will he wait and dry it?”

We loaded the wagon. I took the string out of the inner tube and retied it back and forth across our load. Two dives had yielded a full wagon. We peddled toward home, stopping every few blocks to retie the slippery seaweed so we wouldn’t lose any. We arrived at the bakery well before noon. Nobody was there, except for the kindly old local lady handing out broken cookies to kids like us. We waited in line, watching our loaded wagon with eagle eyes. Only after sitting and eating most of the cookies did the Chinaman show up. He didn’t say anything. He walked up to the wagon and eased a leaf of the seaweed out of our load. He chewed a portion of it off, tasting the black stuff noisily. Finally, he turned to my brother.

“Looks like five pounds’ worth to me. What do you think? I didn’t bring a scale.”

My brother didn’t know what to say. Finally, the Chinaman took out his walled and stripped out five one dollar bills. He held them out to my brother. Mike looked at my sister and I. Our eyes were round. We’d never had five dollars before in our life.

“Okay,” my brother said, and took the money. The Chinaman went back around the corner of the bakery and returned in only a few moments with some old newspapers. He carefully rolled the seaweed into the papers until he had a big solid tube. He was about to turn away when my brother stopped him.

“We get to keep the wagon, right?” he asked.

“Oh, yeah. Next week, right? Next week, same deal?” The Chinaman shifted his load to free up his right hand. He stuck it out toward Mike. Mike shook his hand and the Chinaman left.

“Five dollars, we’ve got five dollars,” my sister squealed. The three of us jumped up and down together. “We can pay for the movies.”

My brother smiled a big smile, which was uncommon for him. “Next week. We’re in the seaweed business.”

We dived for seaweed every Saturday, even during the school year, for the next year and a half. One day the Chinaman stopped coming. We wondered what had happened. For three weeks in a row the three of us showed up with a wagon full of seaweed but no Chinaman. Finally, we gave up, wondering if he was so old that he’d died. Months went by before I decided to go to the bakery and ask some questions. The bakery manager knew the Chinaman. His name was Mr. Ming. He owned one of the Won Ton Chinese restaurants. I went to the restaurant and found him late on a Saturday afternoon. He was surprised to see me and then started apologizing for not coming back to tell us.

Mr. Ming apologetically related the use he’d had for the seaweed we pulled up from Keehi Lagoon. The seaweed was processed to make MSG, or monosodium glutamate for seasoning the food. MSG was frightfully expensive, or had been because it was imported from Japan and the makers of Japanese MSG guarded the supply very seriously.

“Not anymore, though,” Mr. Ming said. “Now MSG made in quantity synthetically and very high quality. I buy whole ten pounds for only two dollars, already processed. I don’t have to do anything.”

He held up an empty cream colored bag. “This a ten-pound bag of the stuff.” The bag said Ajinomoto, the name of the Japanese company that synthesized the special flavor enhancer.

The business had sustained we three kids, allowing for Susan to get her bike, our mom and dad to get real Christmas presents from us and many weekends of movie, junk food and candy, before industrialization had overtaken us.

I shared the story to my mom, who grew up in that area of Waikiki. I asked her what that top intersection pictured was. We think it is the corner of Kalakaua & Kapahulu.

You are exactly correct.

It is indeed that intersection, where I lived three houses away for three years as a kid.

Mahalo,

Jim

We lived in Kaneohe while dad was stationed at the seaplane base ( NAS Kaneohe Bay) in the early 50’s. I didn’t get much of the Haole stuff until I did R&R in ’68. It might have been interesting to grow up there.

Great story.

Navy Corpsman, ’66-’69

It was hard to grow up among children who could not invite you to their homes or come to your home even

though they wanted to. It was hard not to have any of them sit next to you in the cafeteria even if it was otherwise standing room only.

It was hard to shunned from certain ceremonies and events while being apologized to about that very thing.

It was hard to go to the reunion and it was the same.

Hawaii, for a caucasian kid, was tough, so you did the usual, hung with others of your own race.

But there was never any violence and I did like that part. I think it is pretty much the same today.

Semper if,

Jim

Another great story, James. I was stationed at K-Bay from 1988-1991 and remember a lot of the places you were talking about. Both of our kids graduated from Kalaheo in Kailua. Semper Fi!

Thanks Mike, for the neat comment. There were a ton of us service brats over that in that time period.

Thanks for coming on to make a comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Hi James. Once when I was walking down the street near our house in Wahiawa and an Old Filipino man stopped me asking in his broken English (and Tagalog) if I could fix his grandkids bike. “Sure” I said once I figured out what he wanted. The front tire was flat and the chain was off the sprocket. I pushed the bike home and found a front wheel that fit, that held air. I oiled the chain, adjusted it and took the bike back to the Filipino. He handed me a five dollar bill, which I tried to refuse. He insisted, so I pocketed the bill and went my way. I helped my friend with his paper route, and had other neat adventures. Watched all the Japanese horror movies for a quarter at an old Quonset hut outside a sugar cane field. Great memories! Almost made up for all those ”Kill a Haole Day.”

There remains plenty of prejudice in Hawaii, and almost all of it is on Oahu.

the struggle for stuff feeds it. It is instructive for white people to move there in order

to truly come to understand what it is like to be prejudiced against just because of something

as stupid as the color of your skin.

You do not come home to the mainland as a prejudiced person against others after the visit.

Thanks for the instructive and well thought out comment…

Semper fi,

Jim

I went to a mainland college, I know the Asian Hawaii people were not used to being around so many white people. I agree with your comment, a haole in Hawaii will learn what it is like to be a minority.

Thanks for that verification. If you do make friends across racial lines with an oriental person,

and I don’t know why it is that way out there, you will be friends for life.

Funny how real life is as opposed to the way we think it should be.

Semper fi,

Jim

A refreshing respite from your 30 day series which I am very much hating and enjoying at the same time. I very much enjoy your writing and attention to facts and detail. You have an unbelievable ability to engage the reader into your writing and to reflect on their own experiences. You sent me back on a journey to my youth when I used to deliver newspapers, shovel snow (day off school and make money), and other odd jobs. Yogurt keep on writing and I’ll keep on reading.

Well Jack, I much enjoyed reading and smiling at this rather well worded ‘compliment’ of sorts.

That I engage you gives me great pleasure and that you might be taken to old thinking places makes me feel even better.

Semper fi,

Jim

AMEN!

This is a story I remember when I was nine, my dad did body work in the summer i worked for him making 10 dollars a Week doing anything he didn’t won’t to do I learned a lot. I remember him telling me to take the bumper off a Cadillac i was hanging on the ratchet in the air i went and told him i can’t get it lose that’s when i learned there’s no such word as can’t, he said and he handed me a length of pipe and said slide it over the end of the ratchet, i did and to my surprise it broke free. that phrase help me through the Marine Crops,Vietnam and the rest of my life. I passed it on to my children. Thanks Dad,rip Semper Fi

Thanks Jim. I am so happy that I took you to a great place and that you have written on here to offer some of your own life.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, Great story, another Catholic school reject huh? Amazing how things have changed, at 10 to 12 years old, we used to get up at 4:30am and ride to a bakery bout 5 miles away to pick up our newspapers (and hot chocolate and eclaires)then deliver the papers on the way to school. On saturdays my cousin and I would go shooting on our bikes and be gone all day, just had to be home before sundown, can you imagine parents nowadays allowing their kids out Ike that, so much for the American work ethic, how things have changed.

Yes, Felix. By holding kids so close we make them safer when they are young and then expose them to greater danger when they are out there and older.

There is a tradeoff somewhere and we’ve gone too far in the ‘safe’ direction.

Semper fi,

Jim

This absolutely a wonderful story. I hrew up with four brothers and we were constanyly trying to figure out ways to make money. One brother sold Grit a newspaper then but a magazine now and I sold flower and vegetable seeds which came to me in the mail. So many things we did and life was so simple then. Thank you for sharing.

It was, indeed, an interesting place to be a child at that time…

Semper fi, and thanks Nancy…

Jim

You’re like cockleburs, Strauss, you pop up anywhere there’s a bare patch of ground, or a gap in the Ethernet, apparently. Ajinomoto is now one of the largest employers here in southeast Iowa. They first popped up like a giant mushroom next door to a humongous Cargill corn processing facility here. Those clever folks extract a couple of specific amino acids out of the product that’s left over after Cargill pulls all of the starches and oils out of our wonderfully productive Iowa corn. It’s apparently a good business for them as they continue to expand. Just one more ephemeral connection between the Farmer and the Writer.

I was unaware of that John.

I order Ajinomoto off of Amazon in little cloth bags and it takes me back to those old days,

when Accent or the chemical itself was actually called Ajinomoto.

I didn’t know it was a company name really.

Thanks for the additive to the story and bringing it all forward in time…

Semper fi,

Jim

Great story of a by gone era. I was told fishing stories about Keʻehi lagoon by a kupuna who grew up not far from there.

Really appreciate your input Duncan.

Are you still living on the Island?

Riveting Story…….I kept coming back even after 3 interruptions…Another Good Read from you Jim…Just wish that I had More Time.

I truly enjoyed the story and is very similar to many of us in our adolescent years. I was luck, both Mom, and Dad, had a lot of sisters and brothers so I was always allowed to go with them. Some of the younger ones were close to my own age, so we got into things. But the one thing I remember is we never pined and moaned for money from our parents, at least I never did. I always seemed to have my own money because i learned from my entrepreneurial uncles and cousins across the south

Thanks for stopping by and commenting Jim,

I believe so many are missing out on growing into maturity with resolve since we have

allowed society to include so many ridiculous restraints.

Really appreciate your sharing this story of youngsters with an entrepreneurial spirit.

The opportunities we had as youngsters to explore, engage and earn money were phenomenal.

In a way I feel sorry for youth today being shielded from these experiences.

What will they have to look forward to when challenges arise?

Thanks again