I ate ham and lima beans while the mosquitos ate me. The repellant backed them off but there were plenty of FNG mosquitos to replace the ones who flew away. I wondered if the drugged mosquitos flew out over the A Shau, and then finally spiraled in after not being able to fly over the wide expanse. If a mosquito fell from the sky what kind of impact did it make? I finished the can and stuck it into the little hole I’d dug next to my big hole for such garbage. I’d almost asked Fusner about how much stuff was left along the way by moving combat units of men. We had two hundred and some odd ‘swinging dicks,’ and the NVA opposed us with at least that many. So, if every man ate, and then went to the bathroom, without there being bathrooms, twice a day, then how much garbage, to include cans and wrappers and other used up papers and junk, got buried along the way every day? I knew it was one of those vexing questions that nobody would have an answer to, and the asking anyone of would only lead to frowns and shaking heads.

The night came and the Gunny along with it.

“What’s the plan?” he said, his voice almost a whisper.

I knew he was keeping the sound level down because of the nearby command post officers and not how close we might be to the enemy. I looked at him in the growing darkness. The moon was up, but not far enough to add much light to whatever was left of the sun’s waning rays. The Gunny already knew the plan so I wondered what he was really asking.

“What plan?” I replied, knowing I sounded stupid.

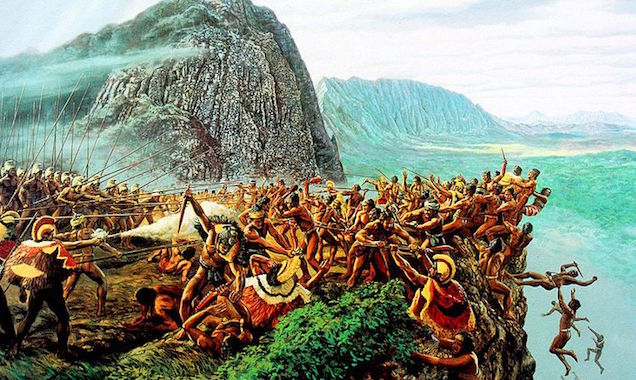

“Kamehameha,” the Gunny said. “What’s going to happen first, the artillery coming in or them attacking. I’ve got a listening post out so we’ll be warned. Good guys from the First Platoon, not FNGs. And where are you gonna be to call in our artillery?”

“How far are the listening post guys out there?” I asked.

“About fifty meters, so they can get back in time, if the shit hits.”

The Gunny was scaring me. We’d have fifty meters of running time to get out of the way when the NVA were coming, and that was it? I’d come up with the Kamehameha Plan because there seemed no other way to get through the night if we were attacked. I had no advance notice of an attack, or whether the 122 mm cannons would fire. Yet the company was on pins and needles, ready and becoming dependent upon me to predict what might happen next. All I saw was a terrible pitfall, once again, if things went wrong. What if there was no attack or enemy artillery? What if the NVA attacked behind our backs, because they’d figured it out. I was just a forward observer, when it was all said and done. I was only supposed to call and direct fire on command, and then get it on positions where it was needed without killing our own men. The word Svengali came to my mind again. Who did I think I was? My hands started to shake. Just when I thought I might be able to stop being afraid of my own Marines it looked like my credibility was about to be flushed down the drain. What if the 122’s fired inland too far and then went left or right or both? Goodbye company. Maybe the smart move would have been to move straight down the narrow path set against the cliff wall, one Marine at a time in the dark, hoping to make it down to the valley floor by morning.

“I’m going to the phony perimeter to wait,” I said, clutching my thighs with both hands. “I’ll take my scout team and call the artillery if it’s needed from there.”

“Your scout team?” the Gunny said, with a short laugh.

“You know,” I replied, weakly. I had no scout team, but the command post was making no demands on Zippo or Stevens.

Suddenly, the shelter half of Casey’s hooch was batted aside and the captain came forth, first in a crouch, looking around, until he saw the Gunny, Fusner and I.

He then stood to his full height and advanced.

“What’s the plan?” he said.

I glanced at the Gunny, my eyes getting bigger. I stuttered a bit and then began to lay out what we hoped to do if attacked.

“Not that Kamehameha thing,” Junior. “I’m not an idiot. I mean what’s our fall back plan in case we’re overpowered, if they do attack?”

I was at a loss for words. I just squatted there, a few feet away, looking up into his expectant eyes. I didn’t have a fall back anything.

“Go ahead, lieutenant, fill him in,” the Gunny said, standing up to face the captain. “You know, what we talked about.”

The light wasn’t good enough for me to read the Gunny’s expression, but everything he was saying had to be a joke. We’d discussed no plan at all, if we were to be overpowered.

“Ah,” I started out, getting to my feet to stall for time. The Gunny lit two cigarettes and handed one over to me. I puffed and then coughed, stalling some more.

“We will fall back orderly to the east, toward the valley wall,” I said, taking another puff of the welcome cigarette and trying to think. “There are two traces that run down from each side that can fit two squads side by side. If necessary we’ll make our way down each side of the face, pulling artillery behind us to cover our retreat.”

“Sounds like a plan,” the captain said. “I’d have a scout posted at the head of each trace during the night so that those ways will be secure, and everyone will know where to go. I mean, if needed.” The captain looked at Zippo and Stevens. “You two follow those orders and station yourself at the heads of those traces.”

“Yes, sir,” I said, cutting the reactions of both scouts off, and hoping they’d say nothing.

The captain whirled around and disappeared into his cave-like hooch so fast it was difficult to follow. His poncho cover was immediately pulled down. The five of us stared at the unmoving cover without saying a word.

The Gunny led us up the hill toward where the fake perimeter line was established.

“What’s a trace?” Stevens said to the Gunny.

“Tell him, sir,” the Gunny said.

I suspected that the Gunny did not know the word. “Trace is a course or path to follow,” I said, so everyone could hear.

We approached the line, which was nothing more than some thrown up bamboo stalks with brush and leaves made to look like some weird farmer scarecrow junk. I looked at the strange collection, disappearing off into the distance as the light dropped. And then I looked at the Gunny, in question.

“In full dark, it’ll be fine,” he said, like he designed phony machine gun perimeter lines all the time.

“There aren’t traces down the face of the cliff,” Stevens said, having remained silent since leaving Captain Casey’s hooch. “There’s only that one trail barely able to handle one Marine with a pack on.

“Correct,” I replied. There were no traces, paths or trails down the face of the Pali on Oahu either, but there just seemed no sense in telling Casey we didn’t have a way out. If the artillery worked out wrong, or if we were overrun then we were dead. Presupposing that we got attacked at all, of course.

“Zippo and I aren’t going over to the cliff?” Stevens asked.

“You’re with me right here tonight,” I said, “at least until we know something for sure.”

“From here,” the Gunny said, extending his arm back the way we’d come, “you run straight, just like you came up and then get the hell down because when these defensive fires open up on both sides this is all going to be a kill zone here.”

“Where are you going to be?” I asked him, when he was done.

“With you,” the Gunny replied, and as the words came out of his mouth a Marine came out of the brush from the downhill sides. I saw immediately that it was Jurgens coming up from the north, where the CP was located and Sugar Daddy up from the southern side.

“We’re all going to wait together,” the Gunny went on. “Thought it would be best if there was some sort of activity on this perimeter, just in case.”

I thought about the listening post only fifty meters to our west, as we all strung out a bit and got down. I motioned to Stevens and when he approached close by I told him to get Nguyen out there, but make sure not to alert and get shot by the guys at the listening post. His face was only inches from mine and I watched his eyes when I was done talking. His eyes were mirrors of my own. We both trusted Nguyen, probably more than we should, but when it came down to it, he was a Montagnard and not an American. Potentially, he could simply head on out to a waiting enemy and reveal everything about what he knew. Which was everything. It was another risk. I looked over Stevens shoulders toward where Nguyen stood, almost fully blended into a nearby bamboo grove. I stared into his big dark eyes, and he blinked, just like before. I knew I had his trust, and I had to give him mine. No matter how aware the Listening Post Marines were, our company was in Indian Country and we only had one Indian.

Stevens said nothing, instead turning and going over to talk with the Kit Carson scout. And then Nguyen was gone, like he’d never been there. For a few seconds I regretted that Steven’s didn’t bother to offer an opinion about the man’s loyalty, but then realized that he had, by saying nothing, and then simply instructing the man.

“We’re at risk here in the dark. They could come at any time although probably not before their artillery hits. Let’s head back to our hooches,” I instructed Fusner, Stevens and Zippo.

I headed back, not sure what the Gunny, Jurgens and Sugar Daddy were going to do because there was really nothing more to be done from the way I saw it and both platoon commanders made me nervous to be around. Either the company was ready to take the hit or it wasn’t, although the difference was life or death. I would never have deliberately planned to be dead-ended at the edge of the ridge cliff face, but I was fast learning that all the planning I had done back at Quantico had been based upon predictability and knowledge of where the enemy was and how much it might bring to a battle. But here we were, more boxed in with almost nowhere to go, than Kamehameha’s opponents had been up on the Pali of Oahu so long ago. We’d also been moving hard and fighting sporadically as a unit for two days and a full night. I wasn’t sleepy but I was jittery, seeing strange things out of the sides of my eyes on occasion, and unable to stay still. I was way past fatigued. I checked my hands while I retraced my steps back to what Casey called the Command Post. My hands were fine, but then they and I were moving, which always helped.

“They’re in their little cubbyholes quite comfortably,” Fusner whispered, after going over to listen at the exposed canvas side of all three snapped-down shelter-halves of the real officers.

I pulled back my own poncho liner, thinking I might be able to hide underneath and get a third letter home going, still carrying the two undelivered envelope in my left trouser pocket. I fell backward as a man rose to his feet and surged forth through the opening. I went to one knee in surprise, not even going for my .45 because of the shock. With the partially full moon’s light I looked up and recognized Lieutenant Keating’s face above me.

“I’m sticking with you,” he said, quietly, and then reached over to help me back to my feet.

“Okay,” I squeaked out, my throat trying to unconstrict.

“What are we doing?”, Keating asked.

“Ah, waiting here until something happens,” I said, truthfully. “Resting as best we can. Once something happens I’ll head back up the trail to where the real perimeter is set up on this side of the slope so I can adjust what artillery we might need.”

I sat on a flat portion of the poncho laying across the jungle floor, wondering what I was going to do with the FNG officer. He sat down beside me.

“I didn’t really understand your plan and the captain has the map in his quarters,” Keating said, near whispering, so the captain would not hear.

I sighed deeply. There’d be no additional letter to my wife. Possibly the last chance I might get to say anything in this life. Instead, I had to go over the plan in detail with a man who wasn’t going to understand any of it when the sky began to fall, if it began to fall. But I had to try. The Gunny had not returned. There was no way to fob the lieutenant off on him. But then, I wasn’t sure the Gunny really understood the plan as much as he thought I did. I spent the next hour going over every detail of the plan, even explaining who Kamehameha was and why I’d named the plan that in order to give it more credibility to the men around me.

“I still don’t understand why you can’t just order these Marines to do what you want them to do,” Keating said, when I was done.

“Really?” I asked. “So, who did you see in your first effort to become a combat platoon leader, Sugar Daddy or Jurgens?”

“Sugar Daddy,” Keating said, not meeting my eyes. “He’s a real piece of work. I knew there were racial problems in the rear, and saw some of them, but I thought all that would have to disappear in combat. We’re all in it together out here.”

“Well?” I said, after a few seconds.

“Well, what?” he answered, actual puzzlement in his voice.

“Well, did you assume command of Fourth Platoon or did you just come on back to the command post?”

“You know,” Keating said.

I said nothing, instead opening one of my breast pockets to get a cigarette out. I didn’t make it. My hands were shaking too much, and I didn’t want him so see, so I clutched them together in my lap.

“Oh, I get it,” Keating finally said. “Yes, I’m back here with you. They didn’t do what I told them to do. And you can’t get them to do what you want them to do either. So, why is everyone following your strange plan?”

It was an intelligent question, and one that would have made me smile sincerely, before I’d lost that ability.

“I tricked them,” I said, flatly. “Remember when you were in Basic School and there was that definition of leadership most of us didn’t pay attention to? Hell, I didn’t even understand it. Leadership is getting other people to do what you want them to do because they want to do it.”

“Sort of,” Keating replied.

“Well, you better understand it now. That ‘because they want to do it’ phrase is about to become the most important phrase of your life. If you live.”

I looked down at Keating’s feet, as he sat with his knees pulled up, like me.

“Your feet are white,” I mentioned, having trouble seeing in the bad light.

“Oh, those are my socks,” Keating said, his tone one of mild embarrassment.

“I had to put on three pair because it’s so rough out here. I put my boots out next to my shelter but when I came out they were gone. All of our boots are gone.”

“Shit,” I said, slowly, breathing in and out deeply, before saying anything else.

“Stevens,” I said, over and down toward his hooch. Stevens unaccountably appeared from somewhere behind me, knelt near my left foot and waited.

“Find the Gunny, and be quick about it,” I ordered him.

“Got it, Junior,” he replied and took off back up the path toward the higher ground.

“See, he called you Junior,” Keating pointed out. “The skipper can call you Junior, and maybe even me, but enlisted men should call you sir or lieutenant.”

“Enlisted men have boots, especially when they’re about to go into full on contact,” I hissed back at him, not hiding my anger.

I heard the explosion at the same instant everyone else in the company heard it, although there was no general alarm or sign that such recognition had taken place. It was a distant explosion but it hadn’t fooled me. I leaped to my feet.

“Let’s go,” I ordered. Fusner was already out of his hooch moving toward me, and Zippo wasn’t far behind.

“Need the Scope, sir?” he asked, in a tone that said he wished I wouldn’t.

“Leave it,” I ordered, “the jungle’s too thick anyway, and I need you to be able to move. Combat gear only.”

“Where we going?” Keating asked, getting to his feet and joining me.

“You’re not going anywhere without boots,” I told him. “You’re just so much cannon fodder at night in the jungle in your bare feet. Get back inside your hooch and stay there until I come to get you.”

I turned to what was left of the team.

“That was a short round,” I said, moving quickly up the path, knowing they were behind me and hoping the lieutenant was smart enough to do what he was told.

“The next round should be over, or dead on the registration point and it’s going to be a hell of a lot louder.” I changed my gait to a lope. I’d left my binoculars at the hooch and just about everything else including my web belt, after pulling out my Colt. Either we were going to make it through the night or I was not going to need water again or more than the six rounds I carried in the .45.

We broke into a run when the second round came in, as I’d predicted. It was a bit long, landing somewhere inside the kill zone, but not far. It did provide enough of a flash of light to reveal the perimeter line, with the Gunny laying down near the side of the broken trail, with Stevens next to him. We went down next to him like cords of wood, the sound of our impact blown away by the shock wave of the exploding artillery round. The 122 Soviet-built cannon round weighed about forty-five pounds and delivered ten pounds of very potent RDX explosive. The round was too distant to throw fragments or debris as far as our position but it was frightening to be taking close artillery fire under any circumstance. I burrowed in, knowing it’d take me a few seconds to be able to talk, but I could still use my hands. I slipped my left fingers into my right breast pocket, tossed the thin C-rations cigarette pack out and grasped two pieces of torn sock. I twisted the end of first one and then the other before sticking them deeply into my ears. The ragged ends hung down nearly to my shoulders I knew, but I didn’t care as the battery of two came blasting in. I knew there had to be twelve explosions coming in the two waves a few seconds apart but I couldn’t separate them. I bounced on the pliant jungle floor, and then kept bouncing, ever so gently, time after time. I pushed my .45 into my right trouser pocket after clicking it on safe. The Colt was not going to save me from artillery.

The first barrage was over in short order but it felt like it had taken ten minutes of time. I didn’t want to get up at all. I wanted to burrow in deeper. It was my first incoming artillery. The first in my life, anywhere. Fort Sill hadn’t put us down range to see what it was like to take fire, and now I understood why. Who would go into such hell, or stay in it, voluntarily?

“They’re going to wait a few minutes until the attack comes before they fire again,” I yelled in the Gunny’s ear, knowing he either had used some sort of ear protection of his own or he was temporarily near deaf from the shock waves.

No obvious attack came right way, however. What came was a whole load of RPG rounds. One after another the rounds rocketed into the faux perimeter. The fireworks of the show was more than anything I’d seen back home. The four pound rounds began detonating with fierce cracks instead of the deep earth-moving and shaking cracks of the artillery. I knew we were in living hell, and it’d just begun.

A body thumped down almost on top of me. It was Nguyen, the teeth of his out of place white smile gleamed in the reflected light of the explosions.

“They come,” he whispered, into my rag-blocked right ear. He held up four fingers in front of my face. “Four hundred,” I heard the Montagnard, who I knew didn’t speak English, distinctly say.

The RPSs continued to come in, but more sporadically. There was no return fire from any Marines, and I was surprised, not only by the terror of the artillery and the RPGs hitting so close but by the fire control of the unit. Like it was in training, but better. The four hundred was rotten news. We were badly out-numbered, and they’d brought up a load of armament. And they were coming. My stomach was curdling with fear, and I so didn’t want to climb out of the welcoming suction of the jungle mud.

I forced myself to my hands and knees. Nguyen was gone, as fast as he’d appeared. I didn’t doubt his report. I reached for the handset, and Fusner was there, knowing just when I’d make my request, but I didn’t call it in. From the time I made the call, it would only take a minute or so to get a ranging round to the registration point I’d picked. I’d have loved to have fired a round earlier or even clued in the battery, but I didn’t trust the enemy not to figure things out or for the radio transmission not to be intercepted. I kept breathing, as the RPG firing lessoned and another battery of two hit the open area near the cliff. The enemy artillery battery was in a tough situation. If they fired too deep they would take out their own attacking force. If they fired short then the rounds would smack uselessly against the face of the cliff. Unless they had a forward observer like me, which I prayed to God they didn’t.

I waited, handset in hand. To get the first battery fire after the ranging round, saying that round was accurate, would take about a minute or maybe two, depending on how good Fire Base Cunningham’s Fire Direction Center and howitzer gunners were. The timing had to be just right. If I got it wrong, then the NVA might figure out where we were set up and pull some trick out of their bag I hadn’t thought of. I waited. And waited. The artillery blasts ended, and the bouncing jungle subsided once more. The rounds had come no closer. They couldn’t come closer unless the battery was informed about where we were on both sides of the slope. I got control of my breathing again. My crotch felt warm and I worried that I’d relieved myself in my trousers, but then shoved that shameful thought aside. What did it matter and who would care, anyway?

My mouth was dry. I wished I’d brought my canteen. Could I even talk?

Fusner shoved his hand toward my free hand. I accepted a small package, and held it up to my nose. I could smell it. That gave me a tug of hope. I was still alive. The package was a folded stick of chewing gum. I put the stick into my mouth and chewed. It worked, as saliva began to flow again. I wondered if Fusner was chewing gum too, and how he knew I’d need it.

The enemy small arms fire began as the third battery of two came crashing in. The distinctive pops of the AK fire so different from the sound M-16s made. I couldn’t see any fire but I knew it was coming from my right, where the NVA had to be. The firing began to move. The NVA was using our own classic fire and maneuver tactics, attacking while thinking they’d either taken out the faux perimeter or shocked whomever was left manning it into uselessness.

I pressed the button and ordered the fire mission. I told the battery that we were in contact, once I coded in and gave them the first registered target. After ‘shot over’ and ‘shot out,’ I knew I was in trouble. I’d been unable to see anything up through the double canopy jungle in the dark. The moon’s wan illumination had been no help. I swallowed deeply and ordered a second round to the same point, to explode its white phosphorus fifty meters higher. I had to have a point of reference or we were all dead. Suddenly, my mind clicked and I instantly pulled the sock rags from my ears to be able to hear the round explode. I stood up, taking a chance. When the word ‘splash’ came over the speaker I stared up and counted “one, one thousand” five times, softly. And there it was. I heard the explosion and picked up a slight flash at the same time.

I plopped myself back down into the mud and stopped paying attention to anything around me. The small arms fire increased in loudness and tempo. Our faux perimeter was being overrun. I closed my eyes and began to see the six grid coordinate registrations I’d set up for a battery zone fire. I got the numbers into Cunningham’s battery, and then carefully stopped to get the adjustment for the first battery of six (or whatever they had) to begin. I had to adjust from the phony position I’d given Cunningham earlier. Instead of ‘left three hundred’ and ‘drop one hundred’ I had to order ‘up three hundred’ and ‘left one hundred.’ I would have loved then, when the battery indicated it was ready, to yell “fire for effect” into the handset, but I didn’t. I called for another ranging round on the first beaten zone I’d asked, for to begin the paraded of fire. This time I asked for one round of high explosive.

Another shattering set of rounds impacted on the open area near the cliff face, the shock of it making everyone duck except me. I was already as deep into the mud as I could get again, with my rags stuffed back in my ears. My H.E. round came in. At ‘splash’ this time I cupped my hands over my ears to help the rags do their job. This round hit five seconds later with a bigger impact than anything the enemy had thrown, as it was only two hundred meters away, almost within the big round’s deadly circular area of death or dismemberment. This time debris showered down for a few seconds. I took my hands off my ears. There was a momentary lull in the small arms fire.

“Yes,” I said to myself and then called for the ‘fire for effect,’ as I drilled myself into the earth as deep as I could, wondering too late about the fact that the battery fire would most probably be delivered by six guns in a circle that was about fifty meters in diameter. That would bring some rounds another fifty meters closer to both real perimeters, and me.

The first battery of six came in. There was nowhere to go except into a fetal position. I knew the first would be the closest and the worst. I unconsciously let go of the radio handset, trying to hide in my own world, as the jungle seemed to explode time after time, and then subside with leaves, branches and even mud plummeting back down. My head rang, and the gum oozed out of my mouth. I could not breath properly without panting and my shoulders quivered. And then the firing continued, but began to grow slightly more distant. I had to breath normally or I was going to pass out. I fought the fear, and strange smells of compressed jungle debris and something else even less pleasant. I knew before getting up that men were dying. I couldn’t hear them because even when the explosions stopped, and I’d pulled the rags from my ears, I still couldn’t hear.

I smiled, curled up on the mud. I was alive. Another distant crashing of artillery thunder came in and I could still hear that. It was enemy fire. Ineffectual and distant. Distant at only about a thousand meters away, but my world had been reduced to only the tiny area around my body. I celebrated at being alive, unaware of any responsibilities I might have or communications I should consider.

I lay there, knowing there would be no accounting for anything in the night. That there was complete silence after the last enemy salvo said everything. Whatever had happened had ended the attack. What the accounting would detail would occur in the morning. I was not aware if the enemy had attempted to charge down the slopes to get away from the awful carnage of the artillery, and I didn’t care. I was alive and it was dark and there was no sound. I could begin counting to myself and wait for the life-giving dawn.

To the Beginning | Next Chapter >>>>>>>

Jim, a simple typo. Welcome home. Dave.

“They’re in their little cubbyholes quite comfortably, Fusner whispered, … => needs a double quote after comfortably, and before Fusner.

As usual sharp eyes are appreciated.

So noted and corrected

Semper fi,

Jim

I don’t know if this narrative is a gift or a curse. I want to write some comments, but can’t formulate the words. I was just a grunt with the 1/501, 101st Abn. in 1970. Carried M-60, walked point, got blown up, came home. I thank you and hate you for your extraordinary story. Keep up the good work and get it done. Can’t wait. I am thoroughly hooked.

Humpe an M-60. those were hard to hump and hard to keep the ammo

clean because you couldn’t exactly drag the cans around everywhere.

The damned clips too. Anyway, thanks for being one of those guys.

Saved my bacon a time or two….and didn’t shoot me, either!

Semper fi,

Jim

Good morning Lieutenant.

It’s almost dawn.

The neighbor’s rooster is crowing.

You up?

Hit us. We need our fix.

Yes, I am mostly ‘up’ by six and ‘down’ by about one a.m., when I am not doing my wandering in the wasteland kind of a thing. The next segment is going up this segment, and as usual I have my doubts because this shit bleeds into total reality and, as with Vietnam, reality scares me. Things come for you in the real world and I don’t necessarily want things coming for me because I write. I’m up and at ’em though and thanks a ton for the asking!

Semper fi,

Jim

Thank you for your story and your service LT.

I did two tours in Nam with the Corps; 67-68 as an 0331 M-60. We worked northern I corps and was hit at KS in Feb 68, about 2 wks shy of my end of tour. I’d just signed my 6 mo. extension papers. Medivaced home and reupped. Went back to Nam in 70-71 as a door gunner/ crew chief on a Ch 53D. That’s my story and sticking to it. We got our ass run out of the Ashau in 67. I went out with a recon unit that wanted an extra gun. We spotted camp fire, at twilight, on another hill. We called in arty but got Puff. Some genius at the head shed wanted us to go over there at daylight and check out the hill. We went and saw that Puff had done an awsome job. Didn’t take long for a group of NVA to spot us. Ended up in a two day running gun fight till we got back to base. That area was bad JUJU ! I got a pinched nerve in my shoulder from jumping off big rocks with the 60 on it. Sent me back to Phu Bai hospital with a GB in a jeep, but that’s another story. Got over any PTSD when I got home by being a biker and bar brawler. Made friends with the ghosts and kind of enjoy the dreams. It’s like going to the movies without the popcorn. Biggest fear is running out of ammo. Sorry to be long winded. Enjoy your book; best of luck, Sir.

You ‘got over’ PTSD by becoming a biker and a bar brawler?

How did you take the adjustment from being in real combat and a real warrior to being

in that artificial macho milieu? I would not think that within the realm of possibility for

someone of your proven metal. How can you fear running out of ammo when you don’t use any?

Ammo gets old and you have to retire it to collector status or get rid of it, in my experience.

Thanks for the detail of your variety of run-ins with the whole Vietnam thing. Appreciate you

making the in depth comment and supporting me in writing the story.

Semper fi,

Jim

Yes Jim, I hear you. I guess I needed the adrenaline rush. I couldn’t just step from War to peace b

Only those who don’t know think that you can make that adjustment quickly

and without mental aberrations. Thanks for coming back and writing here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Outstanding writing. I’m a fan of small unit military actions. I spent 20 years in the actions my 76-96. I spent enough time in a loss miserable Conditions and not in mortal danger, that I have total respect for anyone that went through this. Keep up your writing, I’m one dogface who would buy your books no question asked. Thank you.

Thank you Steven. Small unit military actions. I didn’t know there was such a genre.

Intersting. Anyway, I am writing away here and glad that you made it through without being

chopped into bits, or anything like that. It’s much appreciated that you like my story and

will buy the book. I should have it to Amazon publishing in the next few days, as I continue to

turn out the second volume on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was in Ashua numerous times. Everything that you write about happen to us. I was fortunate enough to have good Officers in my units. I hated it there as much as I hated being in the corner of Loas an the DMZ. I dream at night after reading your chapters, but, I am totally in grossed with your words. Keep them coming

Thank you Dean. Yes, I dream after writing them too! I dreamed that I was alongside the sandy

bank of the river running through the A Shau. The sand was grainy and wonderful. The water strangely clear and

blue, like it never really was. A man parachuted in to land on the sand nearby. He took off his chute, rolled it up and

handed it to me. I took it, realizing the man was my son. Then I woke up. Strange, as dreams will be.

Thanks for the share and the support, and liking the writing.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, I flew Dust Off in your AO from 1968 till 1970. Our call sign was DMZ Dust Off. We picked up a lot of Marines. Thank you for all you and your Marines did to stay alive.

You guys were like angels of the air. You flew no matter what and this part of military life

I must credit to the United States Army. Your helicopter operations in the Nam were just

outstanding, from beginning to end. When we could not get help…you came. When our help would not come

because of incoming…you came. When the weather was awful…you came. Many of us Marines will never

forget that…Thank you!!!!

Semper fi,

Jim

James,

I can’t wait until your next installment, I’ve went back to the first day and started rereading, the story has me captivated!

.

Scott Wagner

Truly appreciate the interest and the enthusiasm. The next segment should be out tomorrow.

God willing and the creek don’t rise.

Semper fi,

Jim

James,

After reading your installments I read the comments and each Vet has a story too that relates with you and their stories are captivating too.

Interesting phenomena for me too Scott. It was and remains unexpected but most welcome.

I reply to each one because they are so heartfelt and valid. Jeez. The stories are kind of like

sometimes as good or better than my own! A lot of truth here and that’s enjoyable too.

Thanks for the comments and the care.

Semper fi,

Jim

Somewhere up above I saw the reference to how Thick some one felt when incoming was hitting. My first incoming was in Dong Ha and I was liaison to the 3rd Marine Div. MI group. We were walking across an open area when rounds from 105′ in North Vietnam across the DMZ start hitting between us and the airfield. I remember lying there thinking how thick the buttons on my shirt felt and how “thick” I felt. I was shown that on we we knew they we firing, by listening, we could hear the tubes pop, and knew it would be 10 to 11 seconds before the rounds impacted. Amazing how far you can go in 10 seconds when properly motivated! Joe Mann, y1LT, US Army

Big mortars! You get to hear the discharge of mortar fire. That plooping or plopping noise every time a round is launched. You can’t hear artillery leaving the tube because except for very rare indirect fire the round is traveling well beyond the speed of sound. That think thing is so relevant. That and flatness and the ridiculousness of hiding behind things that would not stop much more than a BB gun. That’s why each and every grunt who’s faced a .50 or 12.5mm has a healthy quiet respect whenever we see one. Those things on the ground were simply devastating and nothing seemed to stop the rounds. Fifteen feet of berm. No problem. Shit.

Thanks for the comment and the read.

Semper fi,

Jim

These were 105 howitzers, but were pretty well firing at maximum range as Dong Ha was about 6 miles from the DMZ The sound was straight line and the round a much longer flight due to the high trajectory,so in essence they were long range mortars.

Yes, good point Joe. At high angle the howitzer is exactly a mortar, and a damned

powerful and accurate one, as well. Having a full FDC was wonderful, not to mention

Fort Sill trained officers back at the battery. Thanks for the detail.

Semper fi,

Jim

LT,

As I read your account my mind was pulled back to something my Dad told me about his time on Guadalcanal. I heard this in the 1960’s when he was finally willing and able to tell me about some of his experiences.

This is what he said…

“When the big naval shells from the Jap battleships and cruisers came in they glowed red hot, roaring like a freight train… when they landed they lifted us up out of our bunker above ground level. The sergeant and I had dug the bunker with a shelf to sit on so our helmets were below ground level – until the shelling started. The shelling lit up the night sky like the 4th of July.”

How anyone remains sane after enduring what you guys did is remarkable.

Bob

Abut the NGF (Naval Gun Fire) you are so correct. The single time I saw it. Yes, the rounds going by, headed further inland. They were near phosphorescent as they passed, and seemed not that high overhead. That swishing freight train sound that radiated down and then echoed. Those were New Jersey rounds. 16 inch weighing 2200 pounds each! When the B-52’s were too close that same thing happened. You would get bounced out of your dug in hole and then race to get back inside it for the next bomber run. Funny, but those big explosions did not make you deaf like the smaller closer in stuff.

Semper fi,

Jim

Took the C-135 Stratolifter on a medevac to Dover. When we reached cruising altitude I noticed that the plane never “relaxed” as they normally do when reaching cruise altitude. Just kept hauling ass. Asked the crew chief and he told me that some of the litter cases couldn’t be out of intensive care very long so they kept the power on. Foggy on the time but the trip was FAST! One big surprise was when we stopped to refuel at Elmendorf. They made all the walking wounded get off and move into the terminal. Wouldn’t have been so bad but it was in a blizzard so bad we couldn’t see the terminal lights. An airman came to get up and told us to hook onto the belt of the guy in front and not to turn loose. If we did they would find us after the storm. Fueled up took off and it was la la land again. Woke up in Delaware. Hell of a trip, or so I was told.

Thanks Chuck. I had forgotten the name of those plastic bags they

pinned us up on the walls with. Litters. Litter bearers carried stretchers when I was in training.

But I think the bag I was in was called the same thing.

Thanks for the interesting rendition of what happened to you.

Some weird exciting shit going on back in the day.

Semper fi,

Jim

Once I started reading I couldn’t stop. Drove a deuce and a half in the valley a lot in 69 and 70 mostly to FSBs Birmingham and Bastogne. You took me back there. Great read! 26th Gp, 39th Trans Bn, 666th Trans Co.

Thanks for that evaluation. It is nice to be able to write about it now and gain some acceptance.

I am sure not by all, but by the one’s that count. Thanks for reaffirming that.

Semper fi,

Jim

Following and can’t wrap my head around going thru that. Look forward to more.

Well, it’ll soak in over time, if we both have the time to make it through

before I get assigned to a psych ward or worse! Thank you for liking the story and wanting more.

Semper fi,

Jim

Three times I was order to do a live “crater analysis”, at LZ Vera, on 10 and 11 March 1969. I was guarding an Artillery unit on an open ridge. Two semi trucks, full of 105s was in center of perimeter. I got blown around, like a rag doll, by the mortars, artillery and rockets! I really got screwed up from head trauma and hearing problems. Only got blown down once! Saved 50 Montagnards Special Forces, my Armored Cav. Platoon ( “A” Troop 1/10th Cav. 5th Inf. Div.. and the Artillery unit. After destroying the NVA Artillery, I was told by op. coned CO., that I would I would get a Silver Star. Later the Troop First Sergeant, told me I did not get Silver Star, ” because no one ever did it before” Chicken shit excuse, to tell a courageous Lt! Also, never got any of my 10 Purple Hearts! Should have gotten Medal of Honor!

And so, what would you do with the medals today? Oh, the MOH might be okay, except they track and use

those people mercilessly. The rest of them? End up in the attic or basement. Other guys don’t give a shit and many

will question or hold them against you. Unfortunate but true. You did good work it appears from your description

and you ought to be proud of being equipped and able and willing to do that. There is no reward for being a great warrior

and that is why so many get so very quiet.

Semper fi,

Jim

Some of our officers needed to get yheir ticket punched for fame and glory. Some needed to get punched.

And so it was, and so it remains, and so PTSD was born and now reborn all over again.

To live among the non-living is to be safe. Alone. But safe.

Semper fi,

Jim

Ouch!

WELL, Pretty laconic, that comment, but thanks anyway.

I presume the message to be one about the fact that the story reached you on some emotional level.

Semper fi,

Jim

That was a bit pithy as O Reilly might say. Really wasn’t my intent to offend, just a bad attempt at humor. My apologies.

Apologies for what? I think you misunderstand my personality and my

ability to take it. Hey, except for racism and junk like that there is

a place for everyone here on this comment area, which actually is a lot more like

a forum. Thanks for being part of that, including the humor you bring to the table.

Semper fi

Jim

Well to be honest it was a hit at the medal collector and my interpretation of you shutting it down. I’d be leery of guys out to earn medals when others just want to survive and go home. Maybe I interpreted this incorrectly. Looking forward to the next chapter.

It’s funny about the medal stuff, because when you get home the only people who really care about the

medals don’t like you if you have higher ones than they do and other people who you think might positively admire them

don’t have a clue. So, for all those who craved them in the Nam I hope they got them. Mine are in the basement. I’ll bet their medals are there too if

they lived to receive them. Thanks for sticking around Dale and liking the reading and making comments.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, My medals are stored in an old empty peanut butter jar; I think. Great stories Jim. The future awaits your talented work.

The medals. That stuff. Try explaining some of those write-ups compared to what really happened.

Why most medals end up in a peanut butter bottle. Thanks for going, for coming here and reading the story and liking it.

Semper fi,

Jim

Bud, I was a squad leader with the recon plt, 1/61 Inf, 5th ID during the time frame you mentioned in your post. I recall the the attached cav troop was A 4/12 Cav. I cdon’t remember LZ Vera. Was that a fire base? Where was it located?

Somewhere near Pleiku, if my memory serves. Small firebase. I don’t know what they had there. Maybe 4.2 mortars.

Semper fi,

Jim

5 miles from Du Co and 3 miles from Cambodia! We were sent there as pogie bait! Army was testing out new electronics counter artillery dishes. When we ran into the civilian, in charge, we were really pissed. NVA did not need to bracket LZ Vera, because artillery was already adjusted! Civilian jerk was lucky to make it out alive. We did manage to steal his huge box of apples! Every one, was in on this test except the 1st Platoon and Montagnards! If those two semi-trucks, loaded with 105 mm rounds, had been hit, 150 pe0ple would have died!

Sorry about the ambush and idiocy of the hone office, so to speak.

Did not know that Vera had 105s. Glad you made it my friend.

Thanks for commenting and liking the story.

Semper fi,

Jim

I think reading can be as powerful as watching a wide-screen movie from the front row. The human brain can only process so much info at the same time, that means that you must see it again and again to really see the entire movie. That is why so many of us re-read the passages you write because we don’t want to miss anything. Whether reading a book or watching a movie, for some reason my brain looks for the minute details, the obscure mention of an item(like the boots) because those that miss it will not fully get the point later on. I know the Gunny was not only teaching the new officers a valuable lesson, yet I feel he was basically taking them out of the fight, not to save them but to stop them from screwing up a damn good battle plan. And the twisted side of me is waiting to see how Captain Chaos will handle having new boots added to the new resupply list come morning. Shot, out!

Many re-read the passages, which by the way came as a surprise to me,

to resonate with the vibrations seeping out from the writing.

If you can’t ‘feel’ the work then I didn’t do a good job, because I am sure feeling the story as I tell it all over again.

The dawn is coming and Casey and all that are like a sign post up ahead.

This story is no more bizarre than it was to live, and I cannot believe I am here to tell it,

and able to have a forum to do so.

I have a a totally speckled past, and I have plenty of failures back there, just like in the story.

I am not seeking resolution or forgiveness. I am in search of redemption, and all I can do to get it is try to do good works.

And accept that my definition of what those are will be viewed a whole lot differently, from person to person, than

anyone, including me, might believe.

I, and the Monty Python crew, have a lot in common, when it comes to finding this

reflection of the philosophy of life a whole lot more like that of

Life of Brian than of some brave veteran trying to get satisfaction and adulation near the end.

Semper fi,

Jim

Once you’ve had to lay there & listen to the stuff roll in it’s something I don’t think you can ever forget.

Nothing like it on earth. You just don’t know about death from above and the sound

and vibrations and shit in the air. It is just something else to be ‘danger close’ to the big stuff.

Even being far away from a 52 strike was stunning too. The concussion waves ares so brilliantly fog white

when they blossoms out. Something. Then you come home and nobody knows. Or cares.

Thanks for the comment and understanding.

Semper fi,

Jim

Comments does not work!

Hey, lieutenant, you got through a few minutes later.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was an Air Force crew chief on F4D,s at Danang March 67 to March 68. Although considered a REAMF I do know the sound impact and the feeling of incoming rounds. July 15, 1967 we were hit with approx. 200 122mm rockets and I was pinned down on the concrete flightline. I have never felt so THICK in my life. Also with the 68 Tet Offensive they hit us with some of everything, even trying to overrun the perimeter fences. Our sister squadron on July 15 lost everyone of their 18 F4,s and then the 500lb bombs started cooking off. A main landing gear traveled almost 600 feet and demolished our laundry room. My fatigue shirt had so many burn marks it looked liked it had been hit with several birdshot rounds. I had much better living conditions than the grunts I’ll admit but I think I wet my pants a couple times too.

Thick. I like that word. Exactly how it felt to not be able to shrink down enough.

Imagining giant chunks of the hot torn metal is easier for an artillery man who knows the

stuff. Thank you for that comment and for the admission, although we will tell no one!

Semper fi,

Jim

As a sp-4 I don’t think we realized the responsibility you officer’s had and the crucial dicisions you had to make especially calling in artillery at nite and hoping it come in too short. I know that artillery and air support saved the grunt’s bacon many times.I remember the f-4 phantoms dropping the 250 lb. bomb’s it looked like right on top of us,but actually landed ahead of us with shrapnel the size of car doors whipping through the trees.Talk about the pucker factor.We also had a short artillery round come in badly wounded a friend in the platoon from Calif. I remember seeing some of his intestons hanging out from shrapnel.He survived I saw him in the rear at camp eagle after i’d been at Charlie med for malaria and ameobic dysentery.We met up in the co. area and both were gonna be sent back out.It was a strange feeling glad to be in the rear where it was relatively safe, but felt like you should be out there with your brother’s.He said he wasn’t going back out he went awol. Again thank’s for using your leadership skill’s as a forward observer calling in artillery in a timely manner to thawart getting over run by the NVA.

Thanks for nothing that, about the arty calling Tim. It was maybe the single thing

I did the best but it was always a mixed bag. They guys were very wary of artillery because wee always needed it

close and that brought on other problems that didn’t necessarily reflect well back on the guy who called it in!

thanks for the comment and the support.

Semper fi,

Jim

I find myself wanting to go back to when I was young and and so full of life. My army days were some of the best days of my life. I did not think so at the time but now we are old and sick from different ailments caused by being overseas. I would do iot all over again for my country. Thank you Sir !! Your are one heck of a person and to have served under you would have been great. U. S. Army 1968/1970 Korea DMZ

When called We served !!

Well, Roger, as I have thought about so many men responding on here, I would have much enjoyed serving with you, and

would have suffered mightily when you were lost. So I don’t want to relive it all again. Maybe something else to help my country.

I went to the CIA and did that for another number of years. It was different. They actually took better care of their men when they were

in deep shit than the Marine Corps but then it was always just a few of us with huge assets being brought in to bail us out (like three of us in deep shit offshore

in Greece and the U.S. Navy nuclear sub rising up out of the water between us and the bad guys! Shit!). Thank you for the compliment and the nature of

your heartfelt response.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was Army 11B from 68 to 70 fort polk BCT & LPC & AIT

Thanks for being here at all Don. Your own service is reflected in your comment and thanks for that too.

Semper fi,

Jim

A picture is forming, that of an older guy sitting on a rock or something at the edge of a field,speaking quietly to a small group of individuals. From out on the street , they are barely seen but an occasional passerby catches a word or two and wanders near, soon to sit,frozen to the ground, listening , sometimes going to another place few have been. As the group becomes larger, more from the street become curious and are drawn to the ground nearby…..

I only hope that eventually those still out on hte street come to understand why the rest are here..

Thank you Lieutenant.

Wow. That’s a pretty powerful mind picture you formed with your own writing. The older guy. Is that you or me, or all of us?

Those on the street, in the rear with the gear or even making believe they are manly buffs are, for the most part, going to come here

and not like what they read. They want to read about heroics with defined cause and effect, with plans that worked out the way they were supposed

to and with man acting like Tarzan or Rambo as opposed the reality of what we had to become and then come back from.

PTSD is going through the door into reality. That means you leave the fake phenomenal world behind until you come back through that door. And then

pow, you are back. But the world you left looks all wrong. Reality has provided you with a perspective of the phenomenal world that people around you can’t know

and telling the is only a great way to get sympathy and trotted off out into the field, to be the older guy giving out a depth of wisdom that nobody but those who’ve

been can or will understand. And there it is. The world of civilizations is fake. You have become real and are not required to live in that fake world without

pointing out that it’s fake! No pill or group therapy is going to help you with that adjustment. Booze and drugs can give you a break, but then there it is all

over again.

Thanks for the depth, like a depth charge, of understanding and presentation chrly. You are one of us. Brother.

Semper fi,

Jim

I liked the boots and wet pants part. You know how when you get up from the night and have to go take a crap. I was the gunner so I got one of the guys m16s and went just got them blown when they hit us . I got crap all over my lags and boots. Was not funny then but is now. They hit the guy on the gun in the leg he went home.

There are no John Wayne’s in combat. None. Unless you consider guys who show up

and think they can do a John Wayne kind of a thing. There are no Clint Eastwoods either.

There is no room for macho toughness in that environment. There is quickness, snap judgment,

proving value, and being good at what it is that’s directly in front of you that needs being accomplished.

I was equally good at digging and hauling supplies as I was at artillery, and I needed to be because the men

needed to know I was one of them. All the way, up the hill…as we used to say in the corps.

Thanks for that meaningful comment and your care about the story parts…

Semper fi,

Jim

Mr. Strauss, I am somewhat reliving a period of my life set aside in my memories, in reading your words. I left Vietnam after a little less than two years in the Central Highlands, in October 1969. I can almost see and feel the situation on the ground, as well as the artillery hitting, all over again.

The incoming was something, whether enemy or friendly. How can one be prepared for that

in training? Not possible of course, not without having a lot of men and women drop out of that training.

Going back all the time is part of the baggage all of us silently and unknowingly brought home.

Thanks for coming home, being home and reading my stuff.

Semper fi,

Jim

Krump Krump krump krump is a sound I loved to hear knowing the bad guy’s were getting pounded. Of course I didn’t have it danger close before either, which changes the dynamic of the situation totally. Our FO’s didn’t have any maps. I reckon we were just blessed or lucky they were damned good at what they did.

You had an amazing mind and talent for remembering grids. Makes me wonder if any of those men you saved thru out your short tour with your talents ever reflect on that very fact that they wouldn’t have made it out had it not been for Junior. I say Short Tour because of my presumption derived from the book title. If that’s the case then it should have been 30 days in hell. Riveting….

I’m living your experience vicariously thru your writing.

Also……I had to smile at Keating and Casey’s apparent 180 from their sudden abandonment of the regimented rear garrison assholiness mentality when reality of where and what surreal hell they entered.

You had to feel some sort of gratification in seeing them change that made you smile too?! But then again the moment may have been shrouded by the potential of impeding doom.

The night is not over…yet

As always I’m on pins and needles waiting for the rest.

The night is not done, and the day ahead looks a bit grim too.

The Title is Thirty Days Has September because hell was undefined

until that time period demonstrated its existence. Up till then hell was

merely a Catholic family construct to get me to stop masturbating.

Thanks for the very intensive and bright comment. There are a few people like you,

coming on her and making the frown wrinkles rise on my forehead. Thank you. I better get back to work.

Semper fi,

Jim

Kind of thinking the shit may not be over for tonight. You took me back there again. Now questioning my sanity, Did I like it? Waiting for that precious dawn. Thank You for sharing.

Well George, that was kind of the intent. I am not sure of the intent, actually.

Some troll wrote about what poppycock this all was but then was surprised because it was up here

for free. Hard to argue with free. Just don’t read it or don’t come back. The vets come back because they know.

Good luck on making this shit up, except from some of the dialogue and detail that has to have changed in my own mind over the years.

I have my original manuscript written in 1969 and 70 right after I got out of the hospital, my letters home that were all saved

and then my sparse but intense diary from the period. I am working to make this ‘fictional’ work as accurate as I can make it.

Thanks for the comment and the read.

Semper fi,

Jim

There seems to be a bit troll flack showing up on the internet for sure.

Obviously from wannabe “heroes.

I would personally like to state publicly, I listened to this story from James Strauss after he joined our Team in 1970.

I know he kept the manuscripts all these years, as did his wife keep the daily letters.

Anyone wishing more detail I am easy to find

Ever thought about going through retailers like Barnes and Noble with this and other sources. Your gift in writing equals those authors they represent. Thank you again for your service.

Being published by a real publishing house or on the shelves of Barnes and Noble

or even in grocery stores has nothing to do with quality writing.

Nothing. They don’t care and seldom read any of it, really.

Like Hollywood. Mostly crap because they only care about relationships they protect and not the quality of the work.

That they steal or rent real cheap.

No, I have to use Amazon. Plus, this is controversial stuff.

They don’t publish stuff like that, if you haven’t noticed.

Thanks for the thought though.

Semper fi,

Jim

You have me on the edge of my seat. I’m really enjoying your writing. I was too young to serve in Vietnam, but every night I would watch the news with my grandfather. Now I know that many of the news reports were misguided at best about the fighting. My grandfather told the story of him asking me what I wanted to do when I grew up. He said I told him I wanted to be a hippie and fight in Vietnam. LOL. I can honestly say that you guys were my heroes then, and you continue to be. Thanks for your service and God Bless You Real Good!

You wanted to be a hippy and fight in Vietnam. You are a kick, Jim!

We sure didn’t have many hippy-types out there in the bush. And I’ll bet there

weren’t many back in the rear, either. The anti-war movement was in full swing

when I went over, but I did not hear any of it. When I came back, they had a bit more

of my attention. I was, and am, married to a hippy though, if that counts.

Thanks for liking the story and wanting to be a hippy warrior! Made me smile.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim,

I don’t know what to say but I just feel like I need to reply in some way. Your story is awesome and incomprehensible at the same time. I’m honored to have read it. Thank you for your service. Thank you for your story.

May God bless you and the other men who served.

Doing my best to get it down Ed. The service thing, well that’s a matter of opinion, but

I appreciate your saying that. Thanks for commenting and reading on….

Semper fi,

Jim

Ah, the pucker factor; “couldn’t drive a ten penny nail up there with a sledge hammer”. Knowing that the straps on your web gear and the buttons on your cammos were preventing you from getting lower. As I look back, it seems that there were levels of pucker factor.. hot insertion, waiting for them to come into the ambush zone, shots through the parameter and then the close in arty. Then when it was over, the shakes, the shits and the exhilaration of survival. On one hand I wish I had never come across your writing and on the other I can’t wait for the next chapter.

You had to be there, kind of a thing. Kind of difficult sometimes to think and write about

how badly I wanted out of there, especially when some people write in and write about how they would love to have been there.

Until they got there, of course. One can be so tough and threatening back here. Try facing three NVA sappers in the jungle at night

by yourself, or some other form of Vietnam insanity. Macho…gone. Toughness…gone. Life…gone.

To die fighting in with honor. To die begging is with dishonor. As usual, life offers no black and whites, unless it is racial.

You die fighting while your begging, or is it the reverse.

I am glad you came across my writing in order to write yourself. It’s called catharsis, if you can squeeze some out from the presentation of the story.

Thanks for coming and writing and I hope you come back.

Semper fi,

Jim

Dang, Jim. You, LT, are one hell of a good one for relating things from so long ago – and I for one appreciate what it must be taking from you. At the same time, thinking that it is also a bit of a cathartic for you.

Two semi-pertinent observations: First is “Ham and Lima Beans”. As I told you, the Corps “adopted” me when I was 11 and living in the Philippines. The Gunny offered me the can, and called it by it’s proper name, ham and mothers. To this day, I usually refer to them this way when I have them (uncanned!) at home! It just slips out.

Second: I was first introduced to artillery spotting/adjusting by my dad, again in 1957. We were in a helo, moving from where to where I don’t know. But the pilot spotted some small unit action off to port, and circled over towards it. My dad got on the radio, and started talking to the Philippine Army unit on the ground, adjusting their mortar fire. Before he went to the Academy, he had been a signalman on a cruiser, and would often swim inshore, and spot/adjust practice fire on the beach, using semaphore flags. When done, he would swim back to the cruiser, towing the flag bag.

At any rate, he explained to me just what he was doing in the helo. It was a company-sized PA group, with 81 mm mortars, against a group of about 250-300 “Huks”, or Communists. They had never had a spotter in a helo, and it took them a moment, then they started dropping in very effective fire against the Huk guys, and, it seemed to me, take them all out. The helo took a few rounds, kinda scary for a young lad like me. Very precise work, and I was left with a new feeling of awe for my Dad.

Several months later, the Gunny at our base introduced me to all the various weapons, and when we started on the 81, I was able to effectively adjust fire against the “enemy jeep”, thus surprising the Gunny remarkably.

Again, hat is off to a real pro like you – and I still love the smell of “cordite”. My Garand and I both love “making” that smell!

Semper Fi, brother.

The 81mm mortars were great when you could get them. The only problem really

was hauling the heavier rounds around out in the field. Nobody wanted to do that because it

was tough enough going anyway. The sixties were much more portable but did not pack the punch, of course,

and in the bracken you need the punch. Calling artillery is like baking. As much art as it is science.

Some take to it and others don’t like it at all. In my class at Fort Sill I would say that only about twenty

percent of the class really liked to call it and many of those were the Army guys.

Thanks for the lengthy detail of that history and your support.

Semper fi,

Jim

You still fire that M-1. What a recoil and man you have to avoid

flattening your thumb when you change clips. That thing truly having a clip

instead of a magazine. Slammed my thumb in there too many times to recount.

thanks for the history and the time you spent putting it up here.

I am working away on the next segment.

Semper fi,

Jim

I absolutely LOVE firing that Garand! And the 10.3 lb weight absorbs a lot of recoil. The Gunny was a great teacher – concentrate on the front sight, and the target. Let it be a surprise when it fires. All that really works, and I rarely notice either recoil, or the noise. Works with my 9.3 x 62mm “deer” rifle also – shot a deer about sunrise in Nov – first time I had noticed a muzzle blast. Now, THAT startled me! Been there all that time, too. And didn’t hear the discharge or notice the noise. Neck shot at 175 yards, dead right there. Concentrate, Jim, Concentrate! Got some Tracers and AP if you want to try it!

Craig. You are a man among men and I am no longer.

Just the old lieutenant (Junior) out in that proverbial field trying to dispense

not really believable advice and history.

I don’t hunt. I don’t shoot.

I had to kill all that off to survive or I was going to kill some more.

And I was done after the CIA. You’d have thought Vietnam was enough. So I stay away from the pyrotechnics but can still appreciate

and love the smell of Hoppes #9.

I have a big bottle in the basement and every once and awhile open it and take a whiff. And smile. I don’t know why.

With iron sights, at one time, after working on the Garand pretty seriously, I could hold a six inch group at five hundred yards.

That damned thing is good for over a thousand but you’ve got to get a scope or iron sights that will view at that angle.

And then there’s the meteorology to consider, of course.

Anyway, Pleasure to talk about the toys.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great work, and I mean that in the absolute sense. I was a FAC with 2/26, and jumped over to ANGLICO and the ROKMC Brigade when a buddy told me of the opening and encouraged me to do it. Can’t say that was a bad move. 2/26 ended up in Khe Sanh. I spent several months with ANGLICO, then back to the Wing. Never saw anything close to what you’re conveying in these writings, but knew some of us were really tasting it as you’ve written it. Sure gave me inspiration when I was providing CAS with the Skyhawk out of Chu Lai. Sorry you don’t like the Airdales. We sure cared for you.

Thanks for your sharing the darkest part of the war as it hit average American boys.

By the way, I remember all Marine Corps M-1’s being surveyed out and exchanged for the M-14 round about ’62. The Koreans used the M-1 while I was with them, along with water-cooled .30 Cal Machine Guns, but the only M-1’s I saw with the Marines in RVN were the carbines, and not many of them. Where did you smash your thumb?

S/F

Swift. Camp Perry is where my thumb kept getting mashed. Back then they had a course where a tire was suspended from a cable fifty yards a way and then pulled rapidly across the range perpendicular to the gunner. The middle of the tire had a target on it. The damned thing moved just fast enough to be tough to hit. You were no limited on the number of rounds you fired to get hits so part of the effectiveness of scoring was reloading very quickly. You can guess the rest. I did not dislike airdales. We all loved them in a twisted way. They were life when we needed stuff or to get to the rear injured. But they got to leave and up there in the cool air and back to hot food and a rack. We resented the airdales but loved them. Our RVNS had carbines too and M-14s which they sold to some guys going home (you could not get them home, however). Thanks for the usual informative comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

One word…Fuck! Looking at the comments I told you that you were not alone. For you personally glad you are getting this story told!

Terry. Mr. Erudite! Thanks (LOL) for the one word laconic evaluation of the work.

Yes, you were most correct.

I have been as blown away by the comments as many of the readers.

You knew.

Thank you for being along for the ride…

Semper fi,

Jim

I would like to thank you for conveying your experances to those of us both to young to have experanced Vietnam and to old to experance todays conflicts. You imagrey allowes a glimpse into a horrific experance. And you relating your first hand accounts portray some of the emotions our fathers and older male relitives must have experanced during their time over there.this allows me personally a better understanding of some of the elements that shaped them into the men they became and offers me a deeper level of respect for them. You have also answered questions that in many cases may be to painful for famlies to openly discuss. It is because of men like you I can see a healing of long open emotional wounds for those of your generation. So once more with gratitude and respect I thank you not only for sharing this with us but for the sacrifices that lead to the telling of this story.

Hopefully, Eric, the idea is for those of us who ‘bit the bullet’ and got caught in that

meat grinder, to be more able to open up about what happened,

at least by pointing at my story and saying “see,”

that’s the stuff I carried back and have been trying to deal with.

There is no going through stuff like that and then coming home and “getting over it.”

You are not the same human anymore, physically or mentally.

Thanks for the intelligent comment and your support.

Semper fi,

Jim

We’d also been moving hard and fighting sporadically as a until for two days and a full night. (until/unit)

Damn, Lt., nearly wet my pants right along with you!

Finished reading an hour ago and my heart is still pounding, but ready for the next installment.

Thanks for the sharp eye, Richard

UNIT fixed!

You wrote “I hated it so bad but sometimes find myself wanting to be there just one more time. Of course, I would never take that kind of risk, nor would any sane human.”

Which of us was sane then, and which of us is sane now when we go back in our mind? You to the A Shau Valley, me to the Cua Viet River.

There are those who are not going to believe my story or at least say it is all made up.

Those people should read your short comment.

Only those of us who were in those places can never shed them

and only those of us who did those things understand what it is to always being going back,

or totally unaccountably wanting to go back.

Thanks for that bit of credibility.

Semper fi,

Jim

I see going back to Nam and to Army life even thou only in for two years active. The same as I do high school those times are so formative and changing to making us who we have become. And Even thou we know how bad it could be, Now it does not look as bad. Know this I did not have it as bad as you did Jim, or I do not maybe want to think I did. I try to do as much good and be the best I can be because by the only the grace of God I am here. Im always looking for more purpose. I also survived bladder cancer qt 57 so feel I am here to do something more than I have been able to. Don

You are living with the effects of undeniable and unavoidable PTSD. You are dealing with it, as regular citizens are fond of saying,

although have no clue and in most cases want no clue. That you are a man among men cannot be displayed or identified to the ‘normal’ public

because they don’t recognize the signs; no violence, over-committment to friends and family, the drinking phase, the drug phase, and then the search

and never ending quest for redemption because the heart and soul of having gone over to the real world and coming back alive is a terrible want of forgiveness

inside ourselves. And we also do not want others around us to go to that world, through that ‘door’ into that other, and come back like us. Hell, we can’t even talk about it to each other for fear that our giant mortal sins will be greater than the person’s we are talking to….and it’s sure not going to be a VA or outside

shrink who has no clue…but will keep records that will follow you forever.

Thank you, fellow traveler, for writing about it on this site. And maybe for coming in out of the ‘cold’ out there…

Semper fi,

Jim

I know why The 2nd Lt was calling you a svengali.You are able to make people do what you wanted them to do.Good luck with that gift.Not natural but true.If you use it well then you will be fine.

Thanks Billy. Not always, that was and remains for damned sure. I mean about getting people to

do what I want them to do. And define “fine.” I made it through alive, however, somewhat based upon

that dictum. Thanks for the comment and the support.

Semper fi,

Jim

After coming home from Nam and seeing what was taking place at home, there were many times I had wished that I had died there with my brothers who never made it. I often would think how fortunate they were, that they did not have to come and see what had happened to their country after they left.

The country remained the same, my friend. It was we who changed. We went through that portal into a reality

that people living back here in the phenomenal world we helped preserve for them will never ever know, except through us,

and from which they will not and cannot believe. The mud, stink, leeches, pills, repellants, defoliants, cordite, explosions, gunfire, friends bleeding, friends dying, us

bleeding and wanting to die….no, they can’t deal with those things, and do we really want them to? Did we not fight so they did not have to? Because they

could not? They will never hear the helicopters in the night, or the silence while we wait for them to come when we are seventy years old. Still up. Still waiting.

They will never hear the artillery in the distance that they think is the thunder from an approaching storm. They will never understand why some songs, some smells

and some people will cause us to freeze like a January frozen statue in an ice carving contest. No, they never will, and we don’t want them to. They don’t drink to

forget and they don’t understand why we have or must. They don’t take drugs so they can escape who and what they are, because they are not formed from that hard bitten jerky

of awful combat discontent that you are. No, and we don’t want them to. Come forth, back into this world, without regret, because God and the USA allowed you to know truths that

you never expected to know, and would never have chosen to know, but now cannot shed. Or share. So you are here, with us, marching along to a very slow drummer,

beating a refrain of honor won and surrendered so many times, of friends lost, so many times. Here now we did not plan our sacrifice to be silent, as we

pass in this parade of thriving humanity. Know what you helped build and smile at your knowledge, however private it must remain. You have been gifted to

know and they do not, and that is not enough. Nothing is enough….but then that is one of those foundational secrets we were gifted.

Welcome home, fellow marcher to these distant slow drums. You are here, in company, with others who were there

and are now here…but not really because of what we had to leave there.

Enough of you came home to make it matter. Make it matter.

Semper fi,

Jim

James,

What a great read, all I know of “real” war is the little my father told me of his experience in Korea (Marine Corps). You sir have opened my eyes to a world I could not imagine existed. I am amazed at your transformation in just a few days. Day ten feels like month ten.

I’m know I am being selfish when I say how lucky I feel that that war was over by the time I reached 18 and did not have to go. My respect for those of you who did has done a complete 180.

One thing my dad said that has stuck with me all these years is “The only people who want war have never been in it”.

Thanks for sharing with a dumb ass like me who had no idea.

What your Dad says is true Tim. However, there are a whole lot of bellicose warlike men who cruise around the battlefields of the world who never go out in the shit but say they just love it and war itself. There’s a whole Pentagon loaded with them. And many presidents and vice persidents as well. Not too many combat veterans make it into office, George Bush Sr. being the last.

Thanks for your comment and your support.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim: When can we expect to see the rest of the 10th night? I’m on knife’s edge looking over your shoulder. And let us know when you have books for sale; I’ll be happy to buy direct.

Ed

I am writing right now Ed on the second part of that night. I can only churn out about one

segment every three days or so because I have to let it rest and go back and rewrite it and then edit it.

That rewriting and editing usually takes longer than the writing!

Thanks for asking and for wanting to buy the book when I get it out.

Semper fi,

Jim

What you say is true in the personal sense, for those of us who experienced the hell on earth that we went through on the battlefield, but that is not all that I was referring to.

For over forty years, I have watched many of my military brothers who came back from Nam, suffer from mental and emotional issues as well as physical ones. There has always been a hidden element to that suffering, that was ignored and never talked about, which dealt with the betrayal of our government. We went over as proud American freedom fighters who were putting our lives on the line, to free a people that wanted to be free like we were. We did our job and in most cases, we won the major battles that we fought against the communist enemy that we grew up hating. We had them on their knees and their CO was ready to waive the white flag when our government betrayed us, stole our victory and brought us home in shame. Kerry and Kissinger, betrayed our troops in Paris. At the same time, the politicians betrayed us here at home, because of the unrest of the voters over that unending war. That was the result of the hippie generation movement, that had been referred to here in the comments section. Love and peace at the expense of freedom for other citizens of the world.