I followed the buck sergeant down the dark muddy aisle of the Da Nang Hilton, tripping into back packs and other field equipment strewn all over. I’d tucked my flight bag under my bunk, for whatever security that might provide. My watch was my only valuable possession. At some point I knew, since I was a Marine, everything I needed for whatever reason would be assigned to me — if I could just get to the point of distribution where the stuff was issued. The buck sergeant was kind enough to stop, once he was across the plank spanning the benjo ditch, to direct his flashlight back so I could make the crossing in relative safety. Full dark had overcome us, although the light rain continued. The falling drops were more of a sticky mist than real rain and provided no relief at all. In spite of the unending moisture, the sergeant and I walked upon relatively hard ground toward wherever we were going in the dark. The sergeant’s flashlight bobbed up, down and all around, revealing nothing. It only took a few minutes for us to arrive at the side of a dimly lit concrete wall.

“Headquarters,” the buck sergeant said, turning out his flashlight. “Door’s on your right down the wall,” he pointed. “Just go in. The others are already there.”

I wanted to ask the buck sergeant who the others were but he was no longer there. He moved quieter than I thought possible for a  Marine wearing field utilities and combat boots. There had been enough light at the wall to see that he had the new cloth-sided boots, the one’s I’d heard about in training with the special triangular metal strips running the length of their soles. Punji sticks were a common hazard, or so I’d heard — little pits with sharpened sticks covered in human excrement. Regular boots, especially those like mine that had been regular issue back in WWII, did nothing to stop them. I needed a pair of those boots, a set of jungle utilities and a gun. But most of all I needed an assignment.

Marine wearing field utilities and combat boots. There had been enough light at the wall to see that he had the new cloth-sided boots, the one’s I’d heard about in training with the special triangular metal strips running the length of their soles. Punji sticks were a common hazard, or so I’d heard — little pits with sharpened sticks covered in human excrement. Regular boots, especially those like mine that had been regular issue back in WWII, did nothing to stop them. I needed a pair of those boots, a set of jungle utilities and a gun. But most of all I needed an assignment.

I found the handle to the door and went through into a different world. I actually smiled as the door closed behind me. I felt that all my questions were about to be answered and my problems, solved. I was finally experiencing the real combat conditions that the Marine Corps was all about.

I stood at the end of a short hall in real air-conditioned air. I didn’t move, just took in the cold dry feeling. At the end of the hall I saw a water bubbler. I made for it. Hitting the handle, I stuck my face down and let ice cold water pour into my mouth and over my face. I drank until I thought I’d burst.

“Over here,” a voice said from behind me.

I let go of the life-giving bubbler and turned in the gently blowing cool air that seemed to emanate out through a set of wide open double doors. I could see Marines inside the room.

“Welcome to the Nam,” a Marine attendant by the door said.

I nodded. No ‘sir’ here either, but then I wore no rank because I hadn’t thought to dig my bars out of my bag in the dark muddy misery surrounding my bunk. I noted that the floor was made of rough dirty concrete, the only dirt visible in the place. A line of concrete extended through the doors leading to what resembled a cartoon illustration balloon on the floor inside the room. A vibrant blue, luscious and thick rug outlined the cartoon balloon area. Five men stood on the dirty concrete, none touching the clean rug. They stood side by side, not at a position of attention but not really at ease either. There was a space at the right end and I guessed it was for me. I walked to where I thought I was supposed to be.

In front of us a raised dais, covered by the same blue rug material, set at least three feet off the floor. A wooden desk rested imposingly atop the dais, with a lectern to its left. A uniformed colonel, wearing short-sleeve Class A attire, stood at the lectern with his hands gripping the top edges, a look of impatience on his face. The other man sat facing sideways behind the desk, his highly polished, black regulation shoes, crossed at the ankles. His ankles sat up on the edge of the same desk. He leaned deeply back into his swivel chair and worked at lighting a long cigar with a Zippo flip-top lighter.

“Glad to see you all could make it,” the Colonel said, displeasure evident in his tone and a quick glance toward where I stood. For whatever reason, I was late to an appointment I didn’t know I had.

“If I don’t miss my guess, you’re Strauss. You, person at the end,” the Colonel said, staring straight into my eyes. “You don’t seem to have a rank, little Strauss.”

I hadn’t been referred to as little anything since I’d been in high school. There, I’d been five-feet tall in my senior year, the smallest male in my graduating class. I’d grown nine inches as a freshman and sophomore in college. Now as tall as three of the other five men standing in the concrete balloon, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. The public disparagement by the Colonel was just the last frosting on a brutally disgusting and bizarre day. I said nothing, however. I’d reply to a direct question but nothing more.

“Move on,” the big man at the desk with the lit cigar said. I presumed that he was our regimental commander and I was attending a welcoming briefing before receiving an assignment. The desk man blew smoke rings. Each ring was carefully generated thru his pursed lips, and then sent out over his crossed legs and past the tips of his spit polished shoes.

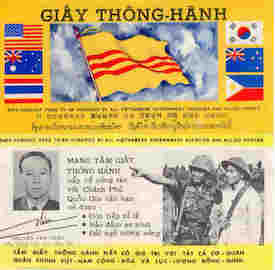

A Chieu Hoi leaflet safe conduct pass, with both sides shown close to the actual size of 6″x3″.

The Colonel went back to talking. He said we’d be given our assignments in the morning, go to supply for our stuff and then be transported out to our waiting units in a matter of days. He talked about military pay currency and why we would be issued some in lieu of U.S. money. I’d never heard of MPC but was surprised that the Marine Corps would give out cash of any kind. The Marine Corps prides itself on being one of the cheapest run outfits in the world. The Colonel launched into a speech which he titled the “Revolutionary Development Doctrine.” It was a ten minute talk about how the U.S. was winning the war by converting enemy soldiers to become allies by joining the South Vietnamese Army. Right after the speech he told us about Chu Hoi passes, which we should be aware of because they were free passes to safety being dropped behind enemy lines by air. Any enemy soldier could use one to cross over to the allied side at any time while out in the field. I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t heard about any of what the Colonel said back in training. Nothing. It was like I was in a different world.

“Chu Hoi my ass,” the big man sitting at the desk intoned quietly, before blowing little circles of cigar smoke through the big rings he’d already generated..

The Colonel ignored him and finished his introduction. He concluded by telling us that the special photo contour-interval maps we would be getting would all have to be specially marked with magic markers. All north/south coordinate designations sent over the radio combat or artillery net would be referred to by the names of popular toothpastes. All east/west coordinates would be named after different kinds of chewing gum. This last part of the briefing stunned me. How could the enemy fail to quickly find out about such a ridiculously easy and stupid code, and then use it to our disadvantage?

“Questions,” the Colonel said, looking up from his notes for the first time since he’d met my eyes at the beginning. He slapped his file closed after only a few seconds, as if the meeting was over.

“That’s it, sir,” he said, turning to face the back of the man sitting at the desk.

“I have a question,” I said into the silence. The Lieutenant next to me elbowed me in warning but I ignored him.

“Oh really,” the Colonel replied, turning back to the lectern.

“When I was in Quantico they constantly beat into our heads that we were to take care of our men first,” I said. The big man slowly brought his feet down from the desk and turned to look at me. I saw the single star on each side of his collar.

I was talking to the division commander. “I arrive here to what?” I continued undaunted. “A muddy concrete walkway leading into a special place in your plush blue rug. An ice water bubbler in the hall. Air conditioning. Electric lighting, for Christ’s sake! What’s going on here? I’m living in that shithole over there with the rest of these guys. What happened to taking care of your men first?”

Nobody moved. I don’t think anyone breathed, least of all me. I could see the Colonel’s name tag. It read “Stewart.” The General’s read “Dwyer.”

It took half a minute for everyone to recover. The Colonel leaned down and whispered in the General’s ear. The General nodded, staring at me with a deadpan expression. The Colonel stood back up.

“The rest of you are dismissed. You can stay,” he said, pointing at my chest.

The other men got out of there so quickly it seemed like they simply disappeared. I stood in front of the two men, not knowing what to expect.

“You’re assigned tonight, right here and right now, so you’ll never spend another minute in that ‘shithole’ over there,” the Colonel said, with flecks of spit coming from the sides of his mouth. “You’re going to ‘Mike’ Company and you’re going tonight.”

“Get him the fuck out of the General’s sight,” the Colonel ordered, looking past me at the Staff Sergeant I’d seen when I entered the room. “Get him his field gear, and then get him aboard an airlift right now, General’s orders,” the Colonel concluded.

“Come on, sir,” the Staff Sergeant said, using the word sir to me for the first time since I’d been in country. The baleful look on his face scared me more than the instant assignment I’d just been handed. I expected to be assigned and go to the field and into combat, but there was likely to be more to it from looking at the Sergeant’s expression.

I followed the Staff Sergeant to a nearby tent at which point everything went like it was supposed to. I got a full pack with everything, a .45 Colt, rations and even an E-Tool. All by the table of organization book and all crisply delivered. The utilities were Korean War issue but I didn’t argue for the new stuff they were all wearing. The old-style combat boots would also have to do.

They wouldn’t let me even go back for my flight bag. They said they’d get it for me and hold it for my return, but I knew it was a write off. I got aboard the waiting Huey. I didn’t realize that helicopters flew at night in the war but, as with almost everything else about Vietnam, I was wrong. I rode in silence except for the ear splitting noise of the chopper’s blades and the awful high-pitched whine of it’s turbine. Nobody offered me ear muffs or plugs, and it was too loud to ask for anything. There were no doormen and no guns on the doors on the chopper. I was in a ‘slick,’ a helicopter used solely for transporting. The crew chief sat directly across from me, staring at nothing in the near darkness, like the zombies I’d never gotten to sleep with in the shithole.

They’d issued me a waterproof flashlight and there were maps in my pack, but it was too dark and windy to take them out and read them. My combat watch said it was just about midnight. How and where we would land I had no idea.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

December 15 1969, landed IN Da Nang Air base, to be assigned to MAG 13 I think it was and stationed on the end of the runway doing A6 SACE Avionics work. Then taken by an Air Force “school bus” up to R&R center at foot of mountain there in Da Nang where there is PX and giant open air mess hall. Waited there for a while and Vietnamese U.S. government paid women were cleaning the mess hall, dressed in their Au-Dais. I quickly leaned back against the wall to feel safer; I did not feel like trusting the women with kitchen utensils. It was then that I noticed high up in the trusses of this giant mess hall the sign above the turn-stiles that read “Welcome to the World”. This was for those returning from service going back to USA. You did not see that sign until you got into the mess hall. That was ominous.

My duty was relatively easy…work on electronic A6 gear in air-conditioned Navy cookie-cutter metal boxes fashioned end-to-end to create an electronics lab.

About six months into my 11 month tour (Nixon gave us one month off our 12-month tour) I was told there would be a new movie at the R&R center, called “MASH”. Went up to the R&R center at base of mountain and saw the movie. Many guys from the jungle came and even though the theater was ventilated, it smelled like a stock-yard, those guys never got a shower, like I did, with heavily chlorinated water. Funny, the movie was, with its referral to pot, drugs, etc., and the smells in the theater were all too obvious and quite a backdrop for such a movie.

About one month later at 2:00 am in the morning I awoke and to an explosion, close by, and I was, it seemed, suspended in mid-air all wrapped up in my mosquito net when it went off. I rushed outside to the smell of gun-powder and smoke in the air. Saw about 300 feet away from me a smoldering mess amidst the row of plywood and corrugated metal hutches. I started in that direction to see what happened and then I realized it was a Soviet rocket that hit not on the runway, but smack dab in our living area. Three men of a four-man poker game where killed instantly. My good friend Dave from Maine, who also worked in my electronics shop, was only 150 feet from the explosion and had retrieved the fourth poker player who eventually died in his arms or when he delivered him to sick-bay. That night changed the war for all of us. The next day no one had the same feelings about the war. Our part in the war was not where the “action” was most of the time. And I can only salute those who were out there in the boonies. The stress must have been immeasurably more for those guys.

Then there was Lenny Hays from Tennessee. He worked in the Da Nang air base lead-acid battery shack (wood building, about 6 feet by six feet in area) adjacent to our electronics lab. His job was to keep the batteries for the Marine F-4’s, Ready For Issue (RFI). The batteries started the generator which started the jet engines. With his work his utilities were constantly getting burn holes from the acid and the supply folks would only allow him so many, to the point where he was always wearing the burnt utilities. Well we had a change of C.O. and this guy was a spit & polish type. A week after our new C.O. took over we were all on the airfield tar mac being inspected in our spit shined boots and starched utilities. I was about three guys down from Lenny and had front row seat to the encounter of the C.O. and Lenny. Here Lenny was in front of the C.O. with starched utilities, only they had holes in them. The C.O. blew a head-gasket. Well Lenny had new utilities from then on. Good for you Lenny.

I also did a stint in the last six months teaching English pronunciation to Vietnamese orphans at the Ang Sang American Evangelical Missionary School. The Marines, Air Force, Army, got together and built them a new school. The old complex was a Jesuit missionary site during French occupation. Every Monday, Wednesday and Friday nights about six of us would hop into the back of a six-by, flak jacket, helmet, rifle sans ammunition, and ride into Da Nang to teach direct method English pronunciation. A friend of mine who arrived same time as me in Da Nang and worked in Hydraulics shop on air base wanted someone to take his place, as he wanted to go live on the perimeter with the Vietnamese. Bored as I was I agreed. It was a good distraction from the hum-drum of electronics shop. I got to know the Vietnamese and felt remorse when it was time to return home. Wonder now if they all were treated well when N. Vietnam over ran them?

This last paragraph I wrote up in the Missouri chapter of the Ken-Burns web site that collected stories from Vietnam vets. Semper Fi

I am sorry, I have not responded to this sooner, Fred.

Thank you for sharing your experiences.

And also thank you for your support in reading.

Have you shared with friends?

Semper fi,

Jim

Thank you sir for writing this. I was a Sergeant in the Army when I went to Vietnam in 1970. I was in the Artillery but was trained as a Forward Observer. I was attached to the 2nd Battalion 327th Infantry. I just started reading you story. What year(s) were you there? Just curious.

I was there in 1968. And thanks for your thanks.

Semper fi,

Jim

I stood in front (of) the two men, not knowing what to expect.

Thank you for your keen eye, Dave

We had edited that for the print copy to be published next week.

But have missed many here on the website.

Semper fi,

Jim

Just started reading. Brings back memories of landing at Cam Rahm Bay. The heat, the waiting, the lack of info, and the not knowing. Went from there to Phu Bai to the 101st(1/501). Thanks for the writings.

Thanks for the kind words. The stimulation of action in the field came at such

a cost to mind and body. Then, when there was any time to rest, the rest was

spent waiting for it all to begin again…for the night to come…so to speak.

Thanks for the kind words and writing the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Got this refered to me by a former Marine pal. It hits close to home. Good reading better writing.

Thanks G.A. as I do read and respond to every comment. Most of the people commenting on this site are almost impossible not to

reply to. Too sincere and too fucking real! And it helps me continue because when I am drawn back in every day to write on

I do not feel alone. I have you guys as my living buddies encouraging me to go on. Strange, I know, but there it is.

Thank you for the comment and the reading.

Semper fi,

Jim

I’ve just started reading 30 Days has September.

I’ve skipped around and read several different section but have become so interested that I’m going back to the beginning and start over.

Very vivid. I can soooo relate.

Bravo Zulu

Thanks for thinking the story is that worth reading. I didn’t know what to think when

I started writing but have been kind of blown away that that many guys and gals might

be interested in the inner workings of a Marine company in combat in Vietnam.

Thank you and thanks for keeping me going.

Semper fi,

Jim

So many of the one’s who went out into the shit never came back, physically or mentally. And then there would have to be ones that could right something engaging and gritty about it. Kind of rarified air, most probably. Glad to be here in the now and in the world of the round eyes….

YES, SCARY INDEED……sounds a lot like I have heard from Some… but, not many seem to talk much….Bad Vibes… Bad Times… Not,.. many good

memories.

Kay F. Romprey – I have rarely talked about my experience in Vietnam. The few times I tried, many years ago, I either got blank stares or they would quickly change the subject. If you want to hear a Vietnam veterans story you must ask. Then please be polite enough to listen but strong enough to hear things that only happen in your worst nightmares.

You are most correct Tim. One must ask these days. Too many bad experiencs trying to tell people about stuff they either did not believe

or if they did certainly didn’t want to hear.

Semper fi,

Jim