THE SECOND DAY SECOND PART

Breakfast in the mud pit was ham and lima beans served with canteen cup holders of instant black coffee. I didn’t ask the Gunny why the other men bothered to pull the cream and sugar from incoming C-rations. It didn’t matter. I remained so scared I was unwilling to impart more of my ignorance by asking questions that probably had no rational answers. I crouched and sipped the coffee from my holder. My Scout Sergeant was named Stevens and I found out that his job was to check around the perimeter and with the platoon leaders to keep me informed. My Kit Carson Scout was Nguyen, pronounced ‘new yen’. He wore no rank, although he had on a utility jacket. His job, Fusner said, was mostly to serve as an interpreter to members of the local civilian population we might encounter and also questions any prisoners we might take. He didn’t speak much English.

“How’s he supposed to interpret when he can’t even understand me?” I asked quietly.

“That’s up to Stevens,” Fusner replied, his voice a whisper, as the rest were nearby. “Stevens speaks the gook lingo.”

Stevens was supposed to interpret my interpreter. My shoulders sank with the continuing insanity of all of it. I ate a few more spoons of the awful C-ration fare before looking up at the rising sun, coming up over the lip of the shell crater.

I realized why I was there. I’d dumbly stood and accused my commanding officers of being Marine scum. What could I possibly have expected, other than to be sent to my death? In truth, I would never have expected anything like that before coming out to the field. Suddenly, I was not only willing to believe it but I understood it. Nobody in the rear area wanted to come out to the field and face maiming or death.

The way they prevented that from happening to them was to send new people coming in off of ships and commercial liners. The Marines who occupied rear area positions, by good fortune or because they somehow served in the field long enough to get out, never left the rear area, I was coming to realize. They kept the best of everything that came into the war zone simply because they understood that the best stuff was wasted on people who were going to die anyway.

“How many?” I asked of the Gunny, sitting a few feet away.

“How many what?” he answered, working on his sliced ham and cracker meal.

“How many casualties are we taking a day?” I inquired.

“Eight KIA last night and three WIA.” Chopper will be in soon to pick up the body bags and the wounded guys in ponchos. You have to sign off on them.”

“Eleven,” I concluded, more to myself than to him. “And how many Marines do we have?”

“Reinforced company. Two hundred and twenty-two, including you and the dead and wounded last night.”

“Eleven out of two-twenty-two,” I said. “So, we’re losing about five percent a day,” I went on. We have twenty days left, if my calculations are accurate.”

“Twenty days for what?” Fusner asked.

“Before we’re wounded or dead,” I answered, my voice without emotion.

“I’ve been here for almost two months,” Stevens said. “I’m still here,” he went on with some enthusiasm. “So what does that mean?”

“Not good,” the Gunny said. “You guys scram. I want to talk to the actual.”

Fusner, Stevens and Nguyen moved quickly out of the crater, leaving their stuff behind.

“Don’t tell them shit like that,” the Gunny said, staring into my eyes. “They’re fucked up enough. None of us are going home. Not in one piece, anyway, and there’s nothing we can do about it.”

“Those guys, and the others, killed the last two sets of officers,” I hissed back at him. “What am I supposed to do? Let them kill me too?”

“It wasn’t them,” The Gunny said wearily, sitting close to me and pulling up his knees. He took out a cigarette. “Funny, we get more cigarettes than we can ever smoke. I wonder if that’s because they know back home none of us is going to die of lung cancer.”

He offered me one. I shook my head in reply. I’d tried cigarettes in high school. They’d made me sick every time. I was in enough trouble without getting sick to my stomach.

“We’ve got a race war going on in this unit, but you’ll find that out real soon for yourself,” the Gunny said, spitting out a bit of tobacco. “The only way out of here is in a bag or on a medevac. You figured that out. You can do whatever you want for as long as you have left. We’re moving out in about an hour.”

“Moving out to where?” I asked, surprised. We’d just been under fire. I couldn’t imagine going anywhere until a secure passage could be figured out or arranged.

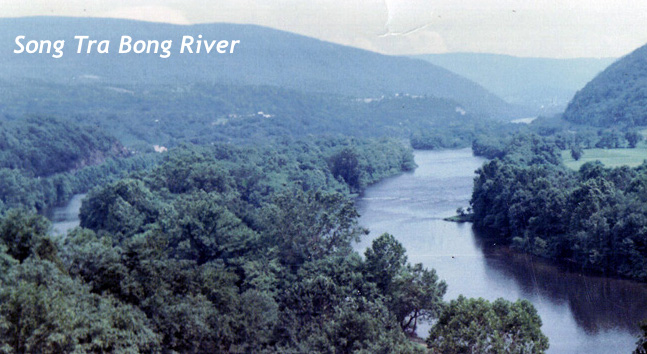

“We move by day and then get hit every night,” the gunny said, pulling out a photo grid map layered over in plastic tape. “They don’t shoot at us in daytime because hell from the air would drop down on them. It’s the way of it out here. We’re on what’s called Go Noi Island, although it’s not. We’re trapped by three surrounding swollen rivers about to get more swollen with the monsoons coming. We move inland under our supporting fires, mostly artillery and retreat toward the ocean under their supporting fires. We’ve got to get seventeen clicks up the Song Bong River, across from Duc Duc, before dark.”

“Who’s laid out supporting fires?” I asked, looking down at his nearly unintelligible map, half covered with black magic marker.

“Outside of me, and now you, nobody has or reads a map, much less can call artillery,” he said. “Accurate artillery fire might just save your life, although I doubt it.”

My stomach would not uncurl. I wasn’t sure I could even stand up when the time came. I looked at his map, my own still tucked into my pack. I knew he was right.  Calling artillery was an arcane science passed on down by the French from before World War II. A fire direction center in the rear, all the way back at An Hoa processed calls for fire and then sent the data to the guns so the battery could fire accurately. The language required to be used on the artillery net was as complex as it was inflexible. Call in, using that radio, without the language and knowledge and you wouldn’t get anything in return no matter how dire your situation or how badly you needed support. You didn’t pick up artillery ability in the field or on the job. You either went to Fort Sill and were trained for six tough weeks or you could forget about artillery support.

Calling artillery was an arcane science passed on down by the French from before World War II. A fire direction center in the rear, all the way back at An Hoa processed calls for fire and then sent the data to the guns so the battery could fire accurately. The language required to be used on the artillery net was as complex as it was inflexible. Call in, using that radio, without the language and knowledge and you wouldn’t get anything in return no matter how dire your situation or how badly you needed support. You didn’t pick up artillery ability in the field or on the job. You either went to Fort Sill and were trained for six tough weeks or you could forget about artillery support.

“They can’t call artillery?” I asked, my voice very soft, almost asking the question to myself. “You can’t call it either, can you Gunny?” I asked, looking the man straight in the eyes for the first time.

“In a pinch,” the Gunny said, his own tone softening for the first time since I’d been dropped in. He looked away.

“Call Fusner and those other guys back,” I said, giving my first order. “Do I call Nguyen a gook too?”

The Gunny got up, climbed to the top edge of the mud pit and gestured before sliding back down. “Nguyen’s a scout. He’s on our side. Only the NVA are called gooks. Some of the men call all Vietnamese gooks but it’s not a good idea. Nguyen’s invaluable when we’re in contact, which is pretty much every night.”

I noticed my hearing improving. The distant ringing was going away. It was a tiny thing but that little fact made me feel a bit better. I grabbed my pack and took out a small stack of folded maps and my compass. I realized I’d need a supply of the plastic tape. Everything around me was wet all the time. I also needed a rubberized flashlight instead of the pitifully cheap metal thing I’d been issued. I found the one to twenty-five thousand quarter map I needed. I realized a second problem about why the unit lacked artillery support, other than the battery I was supposed to be assigned to might have heard about Mike Company and not wanted to provide any fire. Two Eleven was the unit, Second Battalion of the Eleventh Field Artillery Regiment. The maps had very few contour intervals on them. There was almost no rising and falling topography high or low enough to merit a twenty-five-meter difference in elevation. I oriented the map north and south. I’d worry about true north, the math calculation closing the difference between grid north (where the map pointed north) and magnetic north (where my compass pointed). The difference was important for accurate fire but not for what I was going to do.

The Gunny was about to put away his map when I stopped him. “Where do you think we are, precisely,” I asked,

Fusner, Stevens and Nguyen assumed their former positions nearby.

“Where do you think we are?” the Gunny replied, surprisingly.

I looked up from the map toward where he sat concentrating over his own. And then it hit me. He didn’t know exactly where we were, not for incoming artillery fire purposes, anyway. I let him out.

“We’re right here,” I reached over and dotted a point on his map above the Song Bong River.

“Yes, I thought so,” the Gunny replied, quickly packing his own map away.

I took one more compass reading, re-oriented the map slightly and took bearings on two distant peaks to make certain.

Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

“Give me the arty net, Corporal,” I ordered, holding out my hand for the mic.

Fusner handed the instrument over, and then fiddled for a few seconds with the thick radio he’d brought down from his back. The flat bladed antenna was folded back on itself to stick up only four or five feet.

I keyed the mic when Fusner nodded.

“Fire mission,” I said, pushing the transmit button down with my index finger.

“Fire mission, over,” came right back through the little speaker. The words were loud enough for everyone in the crater to hear.

“What are you doing?” the Gunny asked.

I looked at the man coldly, while I held the mic and waited.

“Sir,” he finally said. I ignored him.

“Ipana 44565, Wrigley 61238,” I instructed, reading the magic marker numbers I’d written to mark out position on the map. The fire direction center (FDC) would not process a fire order without knowing the caller’s position for fear of hitting that position. I knew that someone was putting a pin up on a wall map while I waited.

“Ipana 44145, Wrigley 34745,” I intoned, still looking at my map.

“Sir?” the Gunny questioned, deep concern beginning to register in his tone.

“One round, whiskey papa, fifty meters, over,” I ordered, before handing the mic back to Fusner.

I looked at the Gunny. I’d lied to the fire direction center. I’d stated our coded position on the map incorrectly. I’d placed Mike Company almost a thousand meters from where it really was. The second set of coordinates were our own.

“Shot, over,” came through Fusner’s open mic.

I nodded at Fusner, wondering if he had any experience with artillery at all.

He did. “Shot, out,” he said into the mic.

“Oh shit,” the Gunny wrenched out before going face down in the mud.

“Splash, over,” came through the radio. Fusner didn’t respond to that because there was no reason. The splash indication was a calculation by the FDC that your fire mission round or rounds were five seconds from impact or detonation.

A huge Fourth of July explosion took place far above all of our heads.

I smiled, I’d gotten the map reading and calculations right.

The forty-six-pound artillery round of white phosphorus had exploded precisely fifty meters over our heads and the phosphorus rained down like a giant fireworks fountain display. The tails of the phosphorus trailed down almost to the ground before going out.

“Holy shit,” the Gunny got out, crawling up to his knees. “What in hell did you do that for?”

I didn’t reply. I was most pleased. The fifty meters had apparently been sufficient enough to allow all the phosphorus to burn up before impacting down on the Marines of Mike Company. I smiled openly, not at my success or the fact that I had graphically demonstrated that the unit now not only had artillery support but someone who could call it accurately on command. I smiled because I didn’t give a damn if the Marines below, including myself, were hit or not.

I grabbed my map and began to plot night defensive grid coordinates for our day travel. Those coordinates would prove invaluable if we were hit along the way because they acted as registration points. There would be no need to do any plotting at all if we were close to one of them. I’d be able to call a round to the pre-designated point and then adjust fire accordingly.

I got packed up then and got ready to move.

“If we reach the river can we bathe?” I asked the Gunny.

The man just stared back at me, his expression almost inscrutable except for a very faint look of worry and fear in his eyes.

“Yes sir,” Fusner said with open enthusiasm. “The Bong is mostly runoff but it’s a lot better than trying to clean up in the rain. We better get to the units and introduce you.”

“Oh, I think they all got introduced just now,” Stevens said, saying something in Vietnamese to Nguyen that made them both laugh.

The move was unremarkable. The reinforced part of Mike Company was a machine gun platoon added for security, or whatever. Sixteen M60 machine guns, each manned by four Marines. The gunner did the shooting while the others packed ammo, carried the gun and its parts and then set it up when it was ready.

Seventeen clicks was seventeen thousand meters. The clicks were derived by someone with one of those little map distance measuring devices found in training. The machines clicked at the equivalent of a thousand meters the map. Ten miles, or so, was the distance of the hike. Everything was wet so the company moved mostly atop paddy dike walls. It was lousy cover. In fact, it was no cover at all but the rice paddies were filled with human excrement as fertilizer and nobody wanted to have anything to do with them. It was a long hard hike. I hadn’t been in the unit to be there for the last resupply. I had no water in my two canteens, no C-rations outside of the single box that had been in my pack. I refused to ask for anything from anyone there, however. In a very short period of time I’d found out about war.

I was at war with everyone and everything from my own men, my commanding officers, the environment, the insect life, the weather and finally the enemy.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

Spent time on Goi Noi island,

Still have the nightmares. Would like to go back and see it for real.

Was an m60 gunner with two FNG s for help.

The island was quite a pit. I think in some ways I hated it more than

the A Shau because the A Shau was kind of honest. Except for the Montagnards, everyone

hated us. On the island the locals all made believe they were our friends…

Semper fi,

Jim

It sounds to me like calling in artillery requires a mastery of Newtonian physics, like the first one or two years of a science or engineering curriculum. I won’t be surprised if I’m wrong. I once talked to a Coast Guard instructor who claimed to be able to do celestial navigation with simple arithmetic.

Physics had a hell of a lot to do with it. I liken it to mastering sniper skills

Almost the same thing but working with micro equipment and nearly alone. A spotter, like

an F.O. We worked with more meteorology than a sniper encounters and bigger rounds at

longer range, but similar indeed. I got even better with a rifle when I came home

because of it but then had to go hunting and ruin it all. That one deer looked me

in the eyes before it died and that was it. I’d seen that look so many times before.

Sempr fi,

Jim

Something which has changed in the world of fire support is that FDC’s mission now includes working with untrained observers. I was 11C and worked every position in the mortar platoon from ammo handler, to assistant gunner, gunner, platoon sergeant and acting platoon leader over a 4 year tour in the 82nd. During training evals our FDC was always required work through fire missions with untrained obsevers.

I’d say that guys like you paved the way.

I believe the FDC alway shad to work with untrained observers. The problem was, and eemains not with the FDC. There is only so much the FDC can do to

fix a bad call or adjustment. Today is most probably a much better time to call artillery because of GPS and positioning determination. Map reading was a really

big deal back in the day. If you gave your position wrong then the FDC did not know exactly where you were and friendly fire casualties would become a real issue.

Thanks for the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Color blind. Interesting. On my 2nd tour in VN I was with an Air Cav unit and even though I was a grunt I got to fly a number of missions into Laos in 1971. With me was a guy who was color blind. For some reason because of it he was able to see what the rest of us couldn’t see and guide our Cobras in on targets (tanks, trucks, artillery)that the rest of us couldn’t see. At the time we didn’t know about his “impairment”, so our imaginations about how he was doing it took over…

Color blind people, under difficult circumstance but with others present, can

usually draw on those people to help, like with recognizing the color of a smoke

grenade thrown to mark something. Or the color coding used on explosive

devices. The Marine Corps does not permit color blind people to be officers

because of the potential problem of no one being around to help.

Interesting situation.

Thanks for picking up such detail and for reading so deeply.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, your nights must be long….I served with Lima Co 3/5 from Dec 67 until March of 69 as their 81’s and Arty FO. Think I only saw an Arty FO Officer twice in that time period. (They were always being commandeered to fill the Officer slots that became vacant in the other Companies..) Took us a long time to get permission to use Arty in Hue City… would love to trade some stories with you someday…Semper Fi Brother…..and Welcome Home..

Larry, I was 3/5 too but I have to be careful about what I am putting up on the Internet because there is a lot I am

writing that simply can’t be admitted to without shit coming back even after all these years.

Yes, permissions were huge issues over there and if you didn’t lie about your own position many times you could not get fire where it needed to be (village permissions and gun-target shit).

Regular officers and some non-coms could call artillery but not effectively because they never understood the complexities of the FDC and how it all really worked. Thank you for being there with me and thank you for you comments. Semper fi, Jim

Jim, I have been working with a guy the last year that Instructs NCO’s and junior grade officers on field tactics and problems based upon real events from our time… Have generated some very interesting discussions. Were you with Mike 3/5 up on Hai Van 5/68?

Larry, I am trying to keep my actual outfits and personnel out of the

narrative. The people who died, and most of them did, still have relatives out

here and I don’t need them to come crashing down upon me over the events of

so long ago. When I came home and got out of the hospital to await the

disability discharge from the wounds the powers that be said I could spend

my remaining time at any duty station of the corps. I chose Quanitco to

train new lieutenants going over there. That was axed from the get go.

There was no way they would allow someone who’d just come back through

that experience to talk to the guys headed over.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was with 1/27 on the island from June to mid July 68. Transferred to A Co 1/4

So many guys plied that island Dean. I remember one spot named after a Marine

who got hit directly with an artillery shell. You always knew when you were in that part of the island

because of the faint smell in the moist jungle air.

Thanks for what you did and so happy you made it back to the land of the round eyes.

Semper fi,

Jim

Amazing so far..esp for a new 2lt. Plus you have writing talent!

Appreciate the ‘compliment’ Terry.

Have a few life experienced short stories and novels over on

James Strauss Author

Just the smells always burning diesel fuel and s””t. And 115° and keeping a cig going 24/7 to keep the bugs off your face.

Some experiences are difficult to forget.

Always appreciate your input, Daniel

Holy crap. Sad, scary, awesome, horrible.

Attempting to remember vividly just what it was like to come straight from the wonderful phenomenal world of America straight into a fourth world hell where the touch of anything and everything brought pain, misery and/or death. Not the fare of modern literature or Hollywood. There is no going over as a boy and coming back as a man.

You come back as a basket case unless you suffered the good fortune of not having to go out there. What a Godsend to come home from such an outrage against the human condition, having served in a rear area but able

to tell all your friends back here war stories about honor, bravery and ‘growing up.’ Sadly, almost nobody comes home from having been in the shit, not alive, or not in any condition to want to tell any stories at all….