CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

Endurance

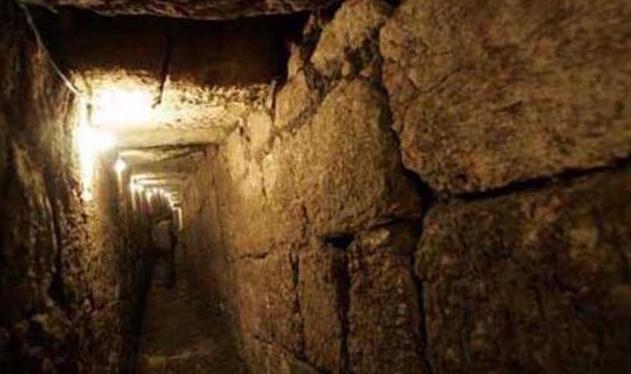

Kasinski and his assistant preceded me through the pipe. Our direction seemed up, although from deep underground it was hard to tell. The cool air bit into my torso, now uncovered by the cashmere coat. I’d spent five thousand dollars of Agency money on that coat, which I had so casually handed over to the boy. I intended to extract a lot more than five thousand dollars from the Commissar, given the opportunity.

Don's Miss any Updates or New Chapters

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

You have Successfully Subscribed!