I tried to sleep in the morning following my meeting with first Haldeman and Ehrlichman, and then Chief Cliff Murray. I was troubled, yet it was too early to get up because my getting up would awaken my wife, and then Julie, both of whom deserved to sleep in because of the worry I usually brought home with me, like a visiting salesman carrying an old tattered and smelly suitcase.

I very gently slipped my right hand under my wife’s left shoulder, as she slept flat on her back. I simply lay there, drawing strength, the way I imagined it, from the tower of reason and power the woman next to me seemed to exude in the face of all threats and danger. I was long-weathered, although my twenty-four years might belie that. I’d been through hell, back again, and then through more hell. It was easy to imagine, as my undetected parasitic hand remained undiscovered, that the mission-driven woman’s power, although not based fully on anything other than my related and transferred experiences, plus the strength of her solid foundations, was re-energizing my own ability to deal with the multi-phased and complicated universe I somehow had something to do with creating.

My wife turned over, slowly but decisively, like she was done allowing me to sap her core energy. I pulled back and looked at my offending hand. I wasn’t alone. I wasn’t engaged in anything more or less other than seeing that the right thing was done. I lay there, next to her gently breathing body, thinking about what I had to do for the good of everyone. I was needed. I knew that, just like I’d been needed by the company of Marines down in the valley, although my temporarily surviving Marines had taken a while to figure that out. Gularte needed me, or he was lost, traveling a path shaped by his traumatic past that would eventually kill him. Shawna needed me, as I was part of the answer to the adult male leader her own father had sort of opted out of by being brutally dominant. The Chief needed me too.

Tom Thorkelson, my boss at Mass Mutual, needed me. I knew his own Marine combat experience, or lack of it, bothered him to his core. There was no way to ever make him understand that he would have been a fine leader in combat…until it killed him, which it did most officers who were any good at it. Accommodating his situation, as a proven combat ‘war hero,’ even if I wasn’t really, was an arm’s length therapy of a kind he’d never get from a psychologist or psychiatrist back in our ‘real’ world that I knew. And I was the tacit Marine Corps hero. He thought that he was, to himself, a poser of that hero he wanted, and even believed himself to be. My acceptance, no matter what it might be perceived to be, was something to him, but also a necessary burden to me. That he was a great man in his own right wasn’t the issue, as I’d already learned a lot about life back at home from his training. No, it was a man-to-man thing that would likely remain unexplainable to and by both of us.

I lay in the secure and comfortable bed next to my wife. Julie was awake and playing in her barred crib, the noisy evidence of an early happy existence evident from the rattling and chortling sounds coming through the open doors between the two bedrooms on our second floor.

I stared at the ceiling knowing I’d have to get moving soon. Personnel at Mainside aboard Camp Pendleton would be open with some warrant officer very likely filling out my departure document, a DD 214, while I was spending time thinking about him, or her. I’d wear my “alpha” green uniform with blouse, upon which would be all my ribbons, my expert medals for pistol and rifle shooting dangling below the rows of those ribbons.

It would be my last time wearing the uniform as a Marine, and I was a little upset with myself for not being happy about that. I loved so much about the Corps but couldn’t explain to myself or others why I felt that love so strongly after all I’d been through since my first day in OCS.

Aside from processing out of the Corps, I had a mixed mess of situations and players; those who were hugely powerful at the Western White House, and whom I was afraid of, the San Clemente Police Department where the Chief, a man I mightily admired, was fighting for the department’s very existence, my budding career in life insurance that was paying me more than all the other sources (not counting my ‘bonus’ awarded by Haldeman), and then the Seven Dwarfs, a gathered collection of oddball characters thrown together to really do what I hadn’t yet fully grasped yet. On top of all those things and players I was the commander of the reserve force operating a growing and full-fledged beach patrol operation. Finally, if there was to be any finally, I was moving ever closer to building deeper ties with the roughly organized, but very effective, members of the San Clemente Lifeguard force.

Getting dressed was easy, although pinning on the ribbons and placing the shooting medals was detailed and painstaking. I went downstairs, while my wife and daughter prepared for the day. Since they didn’t come down to see me off, I left without comment. This mission, the last of my Marine career, was all mine to perform. The drive to the base was quick, with almost no traffic. When I got to the Mainside Personnel building I was directed to an office where I found what I’d expected.

My guess had been correct, the Marine was a warrant officer, a senior one, denoted by the four red ‘pips’ spaced across his gold officer bars. He sat waiting impatiently for me to sign what I had to sign and then get out of his office and life. He hadn’t risen from his chair when I entered, even though I was a full officer and not a warrant, but then I hadn’t expected him to.

“Here’s the package,” he said, shoving a clipboard across the nearly empty top of his Marine Corps issue rubber-topped desk. “I’ve never seen any expiration of active service package that looks anything like this.”

I didn’t pick up on his unasked question. There was no point. I pulled the clipboard toward me, as I dragged my chair to get close enough to handle the envelopes and what was under them. I opened the smaller envelope, pulling out two I.D. cards, one in my name and one in Gularte’s. I noticed that the personnel staff had used my three year old picture for the card, which seemed strange. The most important part of the card was right on the front below my picture. The word “Indefinite” was typed into the expiration box on mine and Gularte’s both. The second envelope held a bunch of stickers, with month and year numbers separate from the base designation, my designation in blue letters on a white background, while Gularte’s was the same but in red letters, as he was enlisted. There were two extra base stickers, both in pink, denoting qualified V.I.P. civilian identification and access. My I.D. rank was 1st Lieutenant and Gularte’s was staff sergeant.

“In three days, you’d have gotten out as a captain, not that it probably matters to you,” the warrant officer stated, watching me closely, the tone of his voice letting me know that he thought that fact funny and possibly demeaning.

Again, I didn’t respond. I didn’t care about being or not being a captain and the warrant officer wasn’t the kind of man I wanted anything to do with other than processing out. I opened the last, and larger envelope. It was a letter on Marine Corps two star stationary, the kind with two big red stars at the very top. It was a letter, signed by Major General Ross T. Dwyer, commanding general of the 1st Marine Division, stationed at Camp Pendleton. It was more an order than a letter. I scanned through its rather short passages. I was to be given whatever permissions were required in order to pursue looking into and observing any operations I might deem I was entitled to. It was the most unusually strange military letter I’d ever read.

I almost laughed out loud. General Dwyer, the same man who’d attempted to send me to my death in the A Shau, the same man who’d pinned my highest combat decorations onto my chest when I got home, and here he was again. He wasn’t the commander of the base, however, so whatever pull Haldeman used to get the letter had to be channeled through someone who’d write it or copy it and not ask questions or give a denial. I knew that it probably wouldn’t matter at all. Who, on a Marine base, was going to question a letter written and signed by a general officer who was also the division commander?

The DD 214 was, I felt, no doubt exactly in order as what it was intended to be. I almost turned it over to sign the back before I glanced down at the very top of the front side of the two-sided form.

“I entered active service in Buffalo, New York,” I said to the obviously bored, but curious, warrant officer.

“You live in San Clemente,” he replied.

I’d been in the Corps long enough to know that, when one leaves the Corps, one was entitled to all the travel and moving expenses from the location of separation from service back to the entry point of that service.

The warrant officer sighed, and then pulled a thick folder from the top right drawer of his desk. He paged through it, making some notes on a legal pad in front of him while I waited, not moving or speaking, not exactly sure what he was doing or why.

“How many bedrooms to your residence?” he asked, without looking up.

“Four,” I replied.

“Three of you,” I presume,” the warrant officer went on, “and driving mileage…”

“Three,” I agreed, not responding to the mileage part he hadn’t gone on about.

“One thousand eight hundred and forty-five dollars,” the warrant officer concluded. It seemed strange, as I sat looking at his busied work with papers and pencil, that he wasn’t wearing a name tag.

“Take this, with your discharge and the other junk, and go over to payroll. They’ll cut you a check. We’re done here,” he finished up, tossing both hands dramatically in the air.

I took the papers, added them to the pile I had on top of the clipboard. I stood up.

“Where’s payroll?” I asked, now certain that if I hadn’t spoken up I’d have deliberately been denied the payoff I was due.

“You’ll figure it out for yourself,” the warrant officer said. He’d never once referred to me using the word ‘sir,’ which didn’t bother me that much but was also strange.

I walked out of the man’s office and back to the front counter where I’d come into the low flat building. I waited for the young civilian lady to notice I was standing before her. The entire interior of the building was painted in some sort of cream shell yellowish white that was just awful in reflection. The floors were solid polished concrete, no doubt polished every evening or early morning with big rotating electric machines soaked in some sort of special wax.

I handed over my DD 214 and the travel expense document the warrant officer had filled out. I was told that I’d have to wait, as the DD 214 needed to be changed to reflect the correct entry point for my service.

A few minutes later, the woman came back to the counter to let me know that a check and the form would be mailed to me. She kindly commented about whether my current address was also my mailing address. The woman seemed a little uncomfortable asking me to sign a blank DD 214 form, as the proper information would have to be typed in and the warrant officer’s signature would then have to appear below my own.

I drove away, not caring about how long it would take for the check to come or the DD 214. If there was a problem when I got the paperwork, then Haldeman or Ehrlichman could deal with it. I took the back way toward San Clemente, just to drive through Las Pulgas, the artillery part of Camp Pendleton, the part where I’d been detailed awaiting my release from service. When I got there, I figured out that there was really no place to go.

There was no place on the entire base to sit or stand in finality and say goodbye to the United States Marine Corps. The parking lot to my final command, the Civil Affairs Group, was empty. I wondered if the Corps had finally disbanded the unit, as I’d always doubted the need for it or the kind of planning for supply depots across the world that might be predicted and planned for by a bunch of young lieutenants waiting to be discharged because the Corps no longer had a need for them. The Volks, with me inside it, sat idling as I wondered how to spend my last minutes in uniform. I turned on the Blaupunkt radio, hit the button for AM and then tuned the bar carefully across the face of the little machine until the needle reached 890. Dick Biondi’s voice came out of the car’s single speaker.

“Now, here’s one for you guys just back from the Nam,” Biondi said, his normally nasal voice low and slow in delivering the words straight to my heart.

“There is a house in New Orleans, they call the rising sun…” came from the small speaker. I’d never been to New Orleans but I knew well the rising sun and being just back from the Nam. I waited until the song played through. I realized, even back home, that I was still, like the closing lyrics of the song, living with “one foot on the platform and the other on the train.”

I drove the Volks home, arriving to find both my wife and Julie waiting.

“Jimmer pretty,” Julie exclaimed, sitting atop her cheap little electric vehicle I’d paid only twenty-nine dollars for.

I couldn’t help but smile.

“It’s time,” was all my wife said, very softly, and I knew she was right.

I went upstairs and changed, carefully placing my uniform into its plastic bag holder. I hung it next to my blues, my whites and khaki uniforms, all in their own matched hanging bags.

I stood and made a decision. I was going to follow the Chief’s advice. I was going from one service, and one uniform to another. I carefully and analytically dressed in my police uniform, replacing my spotlessly spit-shined shoes with Vietnam jungle boots I’d never been issued in Vietnam, but had been able to afford at the police supply store in Santa Ana, thanks to the ‘pay off’ money provided by Haldeman. Those canvas jungle boots, with anti-booby trap inserts, had been only for the guys in the rear with the gear while I was in country. The jungle boots weren’t police issue, but I’d so far never received any order requiring that I wear the leather shoes or boots authorized and paid for by the department.

When I went downstairs my wife wanted to know where I was going.

“I just need to go out for a bit,” I answered, remembering the package I’d left in the Volks. “The identity cards and vehicle stickers came in and I’ve got to get them distributed.”

“I see,” she answered.

I knew she knew that I just needed to get out, do something productive in uniform. I also had to pray that Gularte was home when I went to get him. Nobody was scheduled on beach patrol for the remainder of the day, and the weather would probably have cancelled any normal assignments down there, anyway.

We said nothing more. I left through the front door, Julie’s battery-powered scooter whining away while she wheeled it around every part of the downstairs.

I drove to Gularte’s place and found him home, thankfully. If he hadn’t been there, I knew I’d have gone to the beach on my own.

Giving him his new active-duty I.D. card, with an indefinite expiration and an official window sticker, sold him on dressing out for a supposedly investigative mission on the beach. I said nothing about my own mustering out of the Corps.

Once acquiring the Bronco, and then reaching and getting out onto the beach, Gularte and I drove on the sand toward the compound, through the roughed-up parts of the deeper sand, rivulets of it, with the Bronco’s huge absorbing tires taking most of the beating, but still bouncing the vehicle to the point where both of us wore seat belts. Generally, while on beach patrol, neither partner wore a belt or kept the front side windows closed. With the windows closed, nothing could be heard of approaching danger, or interest, for that matter. Seat belts meant having to free them to exit the vehicle, where such a seemingly minute delay could be the difference between life and death. Gularte was the only partner I had who truly understood that danger still could very well lurk nearby, in spite of our return home from the Nam. The reality or likelihood of such danger didn’t matter to either of us.

The day was nasty, a little wind, a little rain, a bit of blowing spindrift from the nearby crashing waves, but otherwise okay. The stormy surf and high tide of the days before had reshaped the beach from a bifurcated surface of deep warm sand up near the railroad track rocks and nearly flat smooth hardened sand closer to the water’s edge. Now it was rough everywhere except where the waves actually struck the sand and flattened it. Gularte drove rationally for a change, our pace slow and as even as he could make it. Once more, we closed on the small section of beach where the Marine’s towels and other stuff had been placed, not that conditions would really allow, probably ever, for the kind of very close examination we’d discussed wanting to give it at the Dwarf’s meeting.

“We’ve got to get back on the base, you and I,” I said, looking over at him not bothering to look around to check out any beachgoers, because there weren’t any.

“Then what?” he answered, staring straight ahead, almost convincing me that he was a very safe and secure driver of the specially built, but very finnicky, beach-purposed machine we were in.

“We’re going to Horno, near the back of the base, by Las Pulgas,” I replied.

“Horno?” he asked, his tone one of surprise. “All Camp Horno has is the Infantry Training Regiment.”

“That’s where the Marines were based,” I replied.

“Only privates and maybe PFC’s go through Horno, other than instructors,” Gularte said, but he sounded more like he was talking to himself rather than considering what I’d told him and responding to me, so I said nothing.

“They were corporals, all three,” Gularte mused. “If they were corporals, then they simply had to be somehow part of the training detachment.”

“What the hell is that doing there?” Gularte exclaimed, turning the Bronco toward the nearby edge of the sand berm and facing it out toward the ocean. The Bronco’s inadequate wipers thumped away, as I tried to see what Gularte might be talking about. The wipers pushed the collecting water from the windscreen instead of truly wiping it clear and giving me a good view out into the ocean where Gularte was staring.

I ignored the mess on the windshield and stuck my head outside the open window instead, using my left hand to form a visor over my eyes. The wind was slight, coming off the breaking surf, but the mist and spindrift made it hard to see, even across the open air to where Gularte’s attention had been attracted.

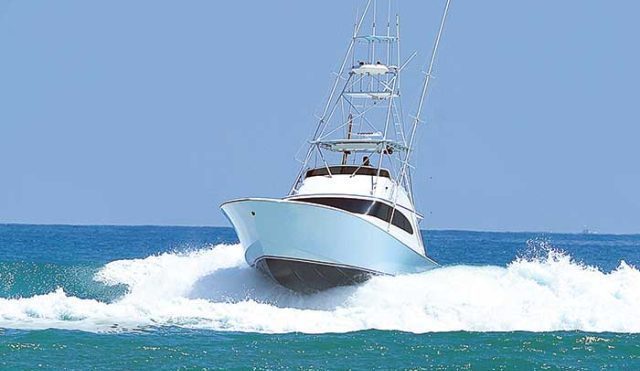

It was a boat, I could see rather dimly. I realized, after a few seconds of adjustment, that it was no regular boat. It was a lengthy beautiful boat of some very expensive design, and it was moving directly toward the shore where we were.

“What the hell’s going on?” I asked Gularte. “What could they possibly be doing this close to the shore and in these conditions?”

“I can’t answer the second question,” Gularte replied, opening his door and stepping out onto the sand, “but I can sure as hell answer the first. That boat is coming ashore, fast and hard.”

As if following Gularte’s directions, the boat pointed directly toward the shore, it’s bow so dead on to us that neither side of it’s hull was visible. I sat mesmerized, staring as the boat came at us, powering directly into the backs of the big swells that were rearing up to break and then expend their energies onto the sloping shore and sand below.

“You going to call it in, or what?” Gularte asked. “What are we supposed to do?”

I jerked back into the real world. I hadn’t even thought about calling in, but we were going to need help, possibly lots of it, very shortly. I pulled the department Motorola handset to my mouth.

“Forty-six-six-seventy-three,” I sent, but didn’t want for Bobby’s receiving response. “We’ve got a boat coming at full speed toward the beach, right in over the surf and it’s going to hit at what appears to be full speed, any second now.”

“You’re not kidding?” Bobby replied.

“We need the guards, equipment to get aboard the craft once it beaches and probably some way to transport victims from the beach.”

“Where are you exactly?” Bobby asked.

“Exactly where the towels and stuff the Marine’s left,” I replied, I replied, not fully thinking about what I was saying. I stopped talking and inhaled deeply as I watched the boat rear up once before falling back, only to rear up again, its bow seeking the sand below it like a bull plunging toward the sharp killing point of a bullfighter’s sword.

I exited the Bronco and moved slowly toward the surf, my feet taking the first hit of sea water as a wave swept up toward and past me. There was no question I was going to get wet, so I ignored it as best I could. My jungle boots were supposedly made to be fully exposed to the most water-logged conditions.

The boat plunged down the front of a big breaking swell, it’s sharpened bow so angled down that it seemed like it would stab right into the sand bottom before it, but it didn’t. Somehow the bow struck the hard-packed sand high enough up so that the forward bottom section of the hull took the hit.

The boat literally bounced, not veering to either side as I thought it might.

Gularte joined me, both of us moving almost unconsciously toward what was fast becoming a major wreck. The waves came in, now up to our knees, forcing both of us to bend into the force of the rushing water.

A swell rose up, bigger than the rest, and struck the boat fully on its flat stern, pushing the craft down in the stern but up by its bow, and thereby sending it forward, almost in a controlled glide, right onto the hard flat surface Gularte and I were standing on, as if waiting for its arrival.

“Back,” I warned, needlessly, as Gularte backpedaling as fast as I. “It’s still under power,” I shouted, “that’s why it came straight in through the waves.”

The boat didn’t stay pushed directly into the shore in front of us for long. Succeeding and unending swells continued to break, striking the boat unevenly across its stern. Slowly the boat began to angle its stern toward the San Clemente Pier, with the shallower water allowing the thrashing propellers to throw sea water up behind it in a low but powerful rooster tail.

“We’ve got to get aboard,” Gularte yelled, plunging forward to approach a thick shoreline that had fallen off the port side facing us.

Before I could say anything, Gularte grabbed the rope. Hand over hand, with his boots pushing against the hull, he climbed madly up the hull. In seconds he was up under the chrome guard rail and standing on the deck. He held the guard rail tightly, as the boat was canting from port to starboard and back severely, almost to the point where it looked from below that Gularte wouldn’t be able to negotiate his way to the main cabin.

I knew there was no way that I could perform the gymnastics Gularte had demonstrated in getting aboard, but I didn’t want him entering the cabin portions of the large yacht alone. I guessed the boat to be about fifty feet long and maybe twelve feet in width. The noise of the breaking sea, along with the wind, the mist and the thumping sound of the boat bouncing up and down on the hard sand prevented any verbal communication. However, Gularte didn’t seem to need verbal communication. He turned his back briefly, and then bent and twisted his torso. A big round lifesaving buoy came sailing through the air toward me. He tried to shout, cupping one hand over his mouth. I knew right away that he was no doubt trying to tell me to get inside the buoy and he’d pull me up.

I grabbed the buoy, hoping I’d fit inside it, before looking up and down the beach. There was no one yet in view, or in hearing distance, to indicate that help was on the way, although I knew it had to be. Bobby was considered the very best dispatcher up and down the coast of Southern California. My last thought about the beach that came to me, before I squeezed myself through the hole set in the center of the buoy, was about coincidence. How was it that the Marines, or others, placed the towels and personal effects right at the same spot that the outlandish yacht we were boarding had just landed not fifty meters from? How was it that the Western White House compound was little more than a mile away? How was it that a large very visible and imposing yacht was not intercepted by the Navy or Air Force, or whomever, before coming ashore where we were?

Gularte pulled hard on the rope attached to the buoy. I was literally jerked off my feet, left to dangle against the side of the pounding hull. I didn’t get a chance to climb at all as Gularte pulled me ever upward. I wondered what I was being raised up into, as there appeared to be nobody operating the boat or, quite impossibly, nobody aboard at all.

Great Chapter, but I seem to not have a link to Chapter xxii. Have all the earlier and now the xxiii, and xiv, but no xii. Please provide me with the link. In past I’ve managed to maneuver by changing the chapter number in the address at the top of the page, but this repeatedly just takes be to xxiii rather than xxii.

Thanks,

Jerry

Hope you got the chapter I sent by email Jerry. Let me know.

Semper fi,

Jim

Dang LT, you seem to have had a penchant for getting yourself into”ticklish” situations, someone who I believe would have been a great friend in my more adventurous younger days! Also I know the difficult feeling you described when being separated from the corps. I anxiously await the next chapter, semper fi

It was tough to leave the Corps, and that part is really true.

That I would return to it over the years was very satisfying, and, in fact,

I still consider myself a Marine first, over all the other careers I’ve had.

Thanks for the great comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another exciting chapter LT.

Thanks Jim, your laconic compliment is anything but laconic to me.

Semper fi,

Jim

After reading this chapter several expletives come to mind but I’ll refrain. What kind of mess have you gotten into? Your more than knee deep in it now.

Eagerly awaiting the next chapter to see where you are taking us.

Too true Phil. Knee-deep or neck deep, maybe. Thanks for the supportive comment

and the compliment of your writing it on this site.

Semper fi,

Jim

Did you two have swords in you teeth as you boarded the yacht? Man you come up against some of the most intriguing situations. Can’t wait for the next chapter, keep up the awesome pace LT. On a side note I can sense a touch of sadness in your leaving the Corp. I faced a somewhat but different time when I was drummed out of the FAA in 1981, yep I was one of those Air Traffic Controller who stood up for what we believed was right. A large number of our group where Viet Nam era vets. We all had a mistrust of Uncle Sam! Semper Fi Sir!!

Thanks for this great lengthy but worth it comment.

Much appreciate you adding your own experiences and how you felt and feel about all of it.

Semper fi,

Jim

“Hard hitting” is a great description for this chapter.

Separation from the Navy was hard for me – as a Navy Junior, plus my four years, made 20 years of Navy life. Really enjoyed much of it, but “the World” had made some major changes there in the late ’60’s, for which I was unprepared. Became a tumbleweed for about 5 years before starting college. That turned out well, as it gave me some direction and purpose. The GI Bill helped me a great deal.

You seem to have weathered that storm, which speaks strongly for your character.

Write faster, my friend – you’ve got me ensnared!

Thanks Craig, for the lengthy compliment, and also sharing some of your own life and experience.

I find so many comments on this site…so straight from the shoulder oper and filled with reality and integrity.

I cannot thank you enough for adding to this whole unusual experience and experiment!

Semper fi,

Jim

Two stories, what a day !!!

I once saw a Tee shirt printed with – I may not have a PHD, but I do have a DD-214 😉

Love that “T” shirt you mention here SgtBob. So many people don’t really get the kind of depth that military service gives almost everyone

who serves, in on way or another. Thanks for pointing that out in your own special way,..

Semper fi,

Jim

I found both this and the previous chapter wait in my email today, so will comment on both here. First off, both of these chapters seem to be a much easier read than most of the others in any of the series. Either you are taking more time in the writing, or you are having them proofread prior to publishing. I do notice some of the things DanC mentions, but I don’t try to be your proofreader. Your mustering out was no doubt a bit of a traumatic experience for you since you have mentioned several times how you loved the Corps. I retired from the Army as a senior NCO and though I loved what I did, for me it was more of ‘time for me to go’. No regrets, just good memories along with a few not so good. I have (and had) a few friends who were lost in the civilian world after getting out. I’m hoping that your comments about taking off one uniform and replacing it with another means you had an easier transition. I’m sure that future chapters will tell us. I got the feeling that maybe the Warrant who completed your discharge was a bit of an ass. I also got the feeling that you recognized that as a ‘Senior’ Warrant, there was no use in you bring that to his attention. I’m still baffled as to how you were able to cope with having to work with Haldeman and Ehrlichman. As to these two chapters, things get mysteriouser and mysteriouser. Keep them coming Lt.

Thank you Rick. What for? For trying to clarify and comprehend the output of my writing and the interior thought process i may go through

to produce it. In truth, I don’t know, myself. I just write away and then don’t look back. Intelligent readers, which you obviously are from

your writing here, help me to better understand me. Much appreciate the compliment you pay me in writing something so comprehensive and substantive

on the site. Thanks so much.

Semper fi,

Jim

Really enjoying your style of sharing your experiences. I was disappointed that I left before making Captain only because it had been a goal from childhood. But now it’s not important at all. But hanging up our uniforms is something only veterans can appreciate.

Looking forward to the next issue and appreciate them coming more often now. Best wishes!!

Thanks Gary for understanding the torn feeling of leaving the Corps, even though I understood that I wasn’t really qualified to remain.

I would serve again, however, as you will see in the novels ahead. Thanks for the liking the work and then writing about it on here

in public.

Semper fi,

Jim

I would hazard a guess that you wrote or thought out, at least part, of this chapter at a much earlier time. It seems like two different perspectives from the first part to the second part. (Both are very good!)

The perspective, Steve, did change, as I relive it to the best of the knowledge I have been able to recall as much as possible.

I didn’t keep a journal back then or notes on anything. It’s just that kind of strange memory…not that I’m always entirely accurate.

Thanks fo thinking I’m smarter than I probably am…although I am admittedly, a bit complex in presentation.

Semper fi,

Jim

I believe you might like to see this:

The Give – Army to Marine:

Yesterday I had my annual visit with my guy at the local VA Clinic. After I sat down in the waiting room an old Marine walked in and sat near me. He immediately started up a conversation asking me what town I lived in and needed some information on where the VA Office was. I told him and also said that the woman that worked there was almost impossible to see because she was rarely at her office. He noticed my metal Huey on my DUSTOFF cap and said that he really liked it. He said that he was in Vietnam 67-68 and had flown in Hueys and some other helicopter but couldn’t remember the name of it. I said that it was probably that funny looking Marine CH-53 but it actually was the UH-34, ugly as hell. He was called for his appointment and when he returned a few minutes later he continued with our conversation. He told me that he was recently diagnosed with cancer and wondered if the VA would increase his compensation. I said that they probably would and told him that he could apply online. He said that his wife did the computer stuff and that he didn’t. He said he was 82 and she was 28. My eyes must’ve opened big time! He laughed and said that he often told that to people to see the reaction. It wasn’t true but I told him that I had wanted to shake his hand when he said that. We enjoyed the laugh even though I had told him that I wouldn’t hold it against him that he was a Marine and I was Army. His doctor had told him that the cancer was not aggressive and that he would probably live to be 90. I told him that he should get that in writing. Again he said how much he liked the pin on my cap. I took it off and gave it to him. It made his day and then he made mine when he said that he was going to tell his wife that when he died that he wanted her to pin it on him so that he could be buried with it. For a moment I was stunned and then said well maybe that helicopter might help him go up instead of down. I can’t recall his name but will pray for him.

Thanks fo much, Gary! Your rendition of your own experience is invaluable and dovetails neatly into what’s become, basically, the story of my now life.

These run-ins between service veterans ae of import and need to be shared as much as possible. I found almost no inter service rivalry back in my time of active

servie, or even after. Once again, movies are not accurate eat all about such things.

Semper fi, and keep on writing.

Jim

“Tom Thorkelson, my boss at Mass Mutual, needed me. I knew his own Marine combat experience, or lack of it, bothered him to his core. There was no way to ever make him understand that he would have been a fine leader in combat…until it”

I had to stop reading at the end of this paragraph . I found it important while still fresh to let you know that in a very similar fashion you have pinpointed something that has effected me personally and maybe a few others . I have realized that as a peacetime Navy vet , I have been seeking the approval of those, who like your self , gave tremendously while serving . Your story helps me to understand myself a bit better . Thank you seems inadequate

That comment means a lot to me, Charley, as the detail written into my works is all about the credibility of those works. Tom’s

communications with me, because he’s reading the works along with you, are also of inestimable value to me…and hopefully to him

as well. He’s ninety now but as clear as can be. His memory of those days isn’t as detailed as my own, but then, that’s just me.

Thanks for the great comment about your own identifcation with what I’m writing about.

Semper fi,

Jim

Good one LT. The plot thickens!

thanks a lot Tony. Short support comment, but it got through to me…

Semper fi,

Jim

WOW ,that hits hard !

Thanks for the really great compliment Bill. That comment ‘hits hard,’ as you put it and I could not appreciate it enough.

Semper fi,

Jim

Wow I can’t wait to read the next chapter

Thanks Donald, I’m writing it just as I am writing this…well, in between, I mean.

Thanks for the compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Good morning, I eagerly await your emails alerting of a new chapter and have to immediately find I place to stop what I’m doing and read. I’ve read everything from the beginning of the first 10 days and have a question, I’ve looked everywhere and was wanting to make sure I wasn’t missing something, is the end of the 30 days and what happened on the hill prior to waking up in the clinic still forthcoming or did I miss something? Thank you for your excellent descriptive writing and your service. God bless you.

Thanks so much Joshua, for this deep and heartwarming comment. Any writer would be honored and so happy to get this kind of support,

and I am so honored and happy, let me tell you! I will continue on, it would just be too hard to quit the people like you who have

come to expect more of the continuing adventure of my life…

Semper fi,

Jim

We know there are no coincidences. The boat came ashore at that particular spot for a reason ! Can’t wait to find out why. Another great chapter James! The plot thickens! Semper Fi!

Life is, indeed, filled with coincidence, but there are such things and then there are those events that give the

impression they are conincidences antil you start to look at the probability of the occurences happening. Thanks for pointing

this ‘coincidence’ out and the questionable nature of it.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks for the great continuing story. I rank the first three books in my top five ever books. Semper Fi, Rick

Can’t thank you enough for that telling and deeply felt compliment, felt when you wrote it and definitely felt when I received it.

Thanks so much on this windy night…

Semper fi,

Jim

On 8/31/2020 I posted a picture on my my FB page of a sunrise, but it could have easily been a sunset, as I saw that day as such. I was leaving a practice that had been my life, and I had no idea of what was ahead for me. Kind of like you mustering out. You were young with years ahead, and they seem to have been filled with all kinds of experiences. My professional career did not end that day as I expected, but it is not near what it was, Even though it is more limited, I wonder how much longer I can continue as I find my mental acuity and tolerance for bullshit seems to be sliding away. Perhaps it is just falling into my role of being an old man, and not enjoying it too much. That said, I enjoyed the symbolism of leaving a life as a Marine behind, and it struck a chord with me.

Please keep it up.

Wow, H.Kemp. Thanks so much for revealing so much about yourself and your own vitally interesting background and motivations.

I am alway surprised by some reader’s comments, and how much wonderful people like you are willing to take a change on here

and say things that others might find fault with. We are twins in many of the things we have been through. I call the reactionship

and affinity twin. Others who comment on this site I also share such a relation with. Most pleasing and satisfying, I might add.

Much enjoyed your comment and totally identify with it.

Semper fi,

Jim

something very early in your magnificent tail struck me, especially when you talked about the Mass Mutual, man and his relationship with the Corps yours and I realized something I had realized a good 25 or 30 years after I left the Corps

The essence of any good leader is honesty, integrity, empathy, compassion, and bravery, both physical and spiritual

very few people will understand what I’m going to say next, but I know it to be true and that is these are also the traits of a great warrior you cannot be a warrior or a hero without these traits

The difference between being a leader in business or in combat, is not that is similar

The difference is combat leaders warriors are participating in a greater good, and their training enables them to act in ways that would go against their spiritual compass, but you react in a situation, and then later it bothers you, but you ultimately come to realize that you did what you had to do for the greater good you cannot be a great warrior without compassion without integrity and that’s what people don’t understand people that know you will look at you Jim, and think he could’ve never done those things. He’s too nice a guy however you did what you had to do for the greater good at the time doesn’t mean you enjoyed. It doesn’t mean it didn’t weigh heavily on you doesn’t mean that it still doesn’t bother you, but it’s also part of what makes you the great man that you are I know and I know from experience my own experience.

What can I say to my great friend Rich? Other than thank you, of course.

Your opinion of me could not be appreciated more, and I feel the depth of it because we meet on regular occasions for

lunch or Marine celebration activities.

Thanks so much for this great tome about the writing and me.

Your friend,

Semper fi,

Jim

WTF James

Nice three letter compliment my friend. Got it. Love it.

Semper fi,

Jim

Your story is really getting intriguing, your descriptive writing is mond boggling for an old EM. Still trying to guess what’s coming.

I am so happy that the rather convoluted mixture of plots and sub plots is continuing to interest you to

the point of actually writing on here about it. So many people never write and I think it’s because so many of

them think their comments will not be read or responded to. Over the last five years I’ve gotten almost 30,000 and answered just about every

last one myself. Thanks for being one of those, well, both of those if you calculate your comment and my response here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Seeing a new chapter just made my good day even better.

Daily searching for yet another episode paid off.

Yet another James Strauss cliff hanger ending that will lure every reader back.

Mystery and intrigue abound.

Actually, I think each of your chapters brings more new mysteries than the solving of past mysteries from previous chapters.

This chapter is another 10 out of 10.

Keep ’em coming, LT.

So much we all need to find out…

As you know, whether you believe it or not, the events I’m writing about all happened almost exactly as I’m writing them.

I’m even using people’s real names and hearing from some of them about my renditions of their part in things. Entertaining

as hell for me as, so far, none of them have been outraged about my revealing stuff that’l lain their undiscussed for many

years. Thanks once more for you friendship and very cogent and timely comments.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, Yes, separation from the service is a huge change.

What will happen on the beach and what it might mean will be revealed – maybe. Joking thinking if you and Gularte could claim salvage rights to the yacht.

Some minor editing suggestions follow:

I tried to sleep-in the morning

Better to drop the hyphen. Sleep-in is a kid’s gathering.

I tried to sleep in the morning

I was troubled, and it was too early

Maybe “yet” instead of “and”

I was troubled, yet it was too early

I simply laid there, drawing strength

“lay” rather than “laid”

I simply lay there, drawing strength

undetected parasitic hand remain undiscovered

Better “remained” instead of “remain”

undetected parasitic hand remained undiscovered

I had somehow had something to do with creating.

Two “had” drop one.

I had somehow something to do with creating.

OR

I somehow had something to do with creating.

traveling a path that his traumatic past, a course of travel that would eventually kill him.

Redundant. maybe shorten.

traveling a path shaped by his traumatic past that would eventually kill him.

was an arms-length therapy

No hyphen. Add apostrophe.

was an arm’s length therapy

psychologist or psychiatrist back in our ‘real’ world. I knew, and I was the tacit Marine Corps hero.

Maybe drop period after “world”

Period after “knew”

Start new sentence with “And”

psychologist or psychiatrist back in our ‘real’ world I knew. And I was the tacit Marine Corps hero.

from his training, No, it was a man-to-man thing

Substitute comma after “training” with period. End of sentence.

from his training. No, it was a man-to-man thing

I loved so much about the Crops

“Corps” instead of “Crops”

I loved so much about the Corps

my budding insurance career in life insurance that was paying

Two “insurance” Maybe drop the first.

my budding career in life insurance that was paying

do what I hadn’t yet fully grasped yet.

Two “yet” Drop either.

do what I hadn’t yet fully grasped.

OR

do what I hadn’t fully grasped yet.

Finally, if there was to be any finally, I was moving

“Finally twice. Maybe drop parenthetical

Finally I was moving

Marine Corps issue rubber-topped desk.

Hyphen seems extra.

Marine Corps issue rubber topped desk.

/Probably gray in color with rounded corners./

/I have a story involving a 2nd Lt, a loaded shotgun, and what happened to a similar desk plus the remains of a report that had taken hours to type./

In three days, you’d have gotten out as a captain

OK for story. Google says 4 years in service to become a captain.

I was to be given whatever permissions needed to be given in order to pursue looking into and observing any operations I might deem to find I was entitled to.

Maybe change “needed to be given” to “were required”

Maybe drop “to find”

I was to be given whatever permissions were required in order to pursue looking into and observing any operations I might deem I was entitled to.

“One thousand eight hundred and forty-five dollars,” the warrant officer included.

I’m not sure about “included”. Maybe “concluded”?

“One thousand eight hundred and forty-five dollars,” the warrant officer concluded.

busied work with papers and a pencil

Maybe trim to

busied work with paper and pencil

if I hadn’t spoken up I’d have deliberately been denied the payoff I was not going to get a check for.

“payoff” and “check” seem redundant. Maybe trim.

if I hadn’t spoken up I’d have deliberately been denied the payoff I was due.

information would have to be typed in and the warrant officer’s signature would then have to appear above my own.

/On my DD 214 my signature is above whoever signed off on it./

Change “above” to “below”

information would have to be typed in and the warrant officer’s signature would then have to appear below my own.

I turned on the Blaupunct radio

“Blaupunkt” instead of “Blaupunct”

I turned on the Blaupunkt radio

If he hadn’t been then I knew I’d have gone to the beach on my own.

Maybe change “then” to “there”

If he hadn’t been there I knew I’d have gone to the beach on my own.

where the waves actually stuck the sand and flattened it

Maybe “struck” instead of “stuck”

where the waves actually struck the sand and flattened it

he was talking to himself and considering what I’d told him than responding to me, so I said nothing.

Maybe change “and” after “himself” to “rather than”

Change “than” after “him” to “and”

he was talking to himself rather than considering what I’d told him and responding to me, so I said nothing.

that neither side it’s hull was visible

Add “of” after “side”

that neither side of it’s hull was visible

full speed, any second now,”

Period instead of comma after “now”

full speed, any second now.”

I replied, not thinking what I was saying fully through.

Maybe drop “through” and move “fully” behind “thinking”

Could add “about” after “thinking”

I replied, not fully thinking about what I was saying.

stab right into the sand

bottom before it

Backspace to connect sentence fragments.

stab right into the sand bottom before it

almost in a controlled guide

Maybe “glide” instead of “guide”

almost in a controlled glide

boat bouncing up and down on the hard stand

“stand” could be either “sand” or “strand”

boat bouncing up and down on the hard sand

OR

boat bouncing up and down on the hard strand

Blessings & Be Well

Again,

Many, many thanks,

Dan

This journey is easier with you on board.

Jim