Chapter XXIII

The trip onto the base was quick and easy, although getting through the gate for the first time without having to travel ten more miles to Mainside to sit, qualify for, and get a base sticker, was a bit problematic. The two guards were suspicious of the car, which I had the registration for but had forgotten the USAA auto insurance packet back at the hotel. They motioned me to the far side of the tiny guard booth, but then everything changed when I got out.

“Holy hell, lieutenant, you okay?” the Corporal said, noting the fact that it had been difficult for me to extricate myself from the seat and stand upright.

James – reading the end of this chapter my heart almost jumped out of my chest. Let me preach on…

I finished 30 Days Has September then lost track of your writing as life got in the way.

Back in Mid February of 2020 a friend and I were returning from a 5 week trip through northern Thailand, Northern Laos, Cambodia, and back through Hong Kong. We were scouting old CIA sites in Laos for a novel my friend was writing. We had very Little knowledge of this Covid thing but almost got stuck in Hong Kong. Then my son at W & M came home in March when colleges we’re closed for the last few months of his senior year. He lived with us for a year as the Covid turned Life upside down for us. Fortunately he graduated and is gainfully employed living in Richmond

However, I’ve started the Cowardly Lion and am focused! I read each chapter with a rapid heart beat!

This chapter was particularly interesting. I completed USMC MOS 2533 radio school June ‘67 at MCRD San Diego, and I reported to my first duty station in the Fleet – HQ Battery, 2/13 at the beautiful Camp Las Pulgas. A few months later was sent to Kaneohe Bay 1st MAR DIV Interrogation & Translation School for Vietnamese language. Returned to 2/13 Pulgas December ‘67. Second week of Feb ‘68 2/27 and 2/13 were sent to DaNang with 4 days notice. It was confusion at best. All short timers for Nam were sent to other units. I never went through Staging BN at Las Pulgas. The only training I had was rudimentary Vietnamese language.

I can’t wait to finish the next chapters as I have some similar experiences as a Corporal returning to stateside duty from VN with no uniforms and sent to Quantico as Student Demonstration Troops PLC / OCS for my last 5 months of active duty. Quantico MB and especially OCS didn’t like marine VN veterans returning with absolutely no uniforms and looking a little scraggly. Will share later. Thank you and hope your healthy.

This is one of those comments that slipped away somewhere. Thet’s happened a few times now and I don’t understand it. This comment re-appeared today although I never saw it when it was written.

Thanks for such a great rendition of your own experience here. I am so happy to be writing Cowardly Lion as it is much more accepted than I thought it would be. I was living history but

the details are no more intensely believable than those that occurred and were written by me in Thirty Days. Wild times. You also describe those times. Everything in the rear and back home, when it came to military was almost all about appearance. Appearance the physical training, yet, combat is so much of the mind.

Thanks for the length and oh so qualitative comment.

Sorry about the time that’s gone by.

Semper fi,

Jim

Hard to wait for the next chapter in your life . And I will want a signed copy of the finished book to complete my collection. Already moved to your other writings quit awhile back I am hooked lol !

Thank you for your support, Don

James: I’ve chimed in once or twice with general and positive comments. No edits since you’ve good a great group of volunteer editors.

Just wanted to say that this time I got the.notification of two chapters as I was starting a short hike up Sweeney Ridge in Pacifica. Couldn’t help myself so I stopped under the shade of a pine tree to read them.

Delightful writing in a delightful setting. NB.

Glad to hear you have been enjoying the story, Nick

Share with your friends.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks for another Barn Burner LT. Love it, would give my soul and first born for that Pony Car!

In truth, Joe, it wasn’t that great a car. It went like a bat out of hell and the feeling in the seat of my pants has never been matched,

but it wouldn’t even come close to beating a Tesla, any Tesla, and it didn’t have air conditioning, a decent heater or much of anything else that

worked very well. It was beautiful compared to almost any cars today (who thought that when the Japanese brought their cars here that all cars would

end up looking like them?). Thanks for the compliment and support.

Semper fi,

Jim

Too bad you don’t have the Goat today,,,,,,worth a small fortune!!!

Intriguing James (LT). Thank you for your service and sacrifice, and Welcome Home! I have been following you all along, since the first Ten Days. Tremendous and amazing story!

As a side note, I ordered “Thirty Days has September” on 4/5/21 and it has not arrived as yet. My order number is 38588. I would appreciate if you could check on it. I plan to order the “Cowardly Lion” when it is finished as well. Thanks so much. Marine Airwing Danang 1965.

Which of the three did your order? Send your address right away and I will get off the order

as I have no time right now to check the records. Thanks for letting me know.

Semper fi,

Jim

Hello James,

I have been along the whole way as well. I have not commented but love reading all of them. I did not receive my order either… I tried emailing a few times. Stay well…

[Order #38419] (February 23, 2021)

The books will go out later this morning USPS. found you back there. Don’t know how your name got checked off as having been sent.

My apologies. Thanks for sticking with me.

Semper fi,

Jim

tracking 9549 0127 7683 1222 5644 47 USPS

no worries sir….. Thanks a bunch.

Another really great chapter – thank you.

I figured that you would be selling the car, which was almost impossible for your wife to drive. Shame, though, leaving all of Micky Thompson’s fine work behind.

I have no idea where my ribbons, etc., are. Moved too many times. Hopefully in this house until I get graduated from this life.

Semper Fi, my friend. Keep up the good work.

God knows what happened to the car and how much it would be worth exactly as Mickey built it, with his scrawled signature on the dashboard.

Semper fi,

Jim

As always your true faithfulness and love to your work and family comes through with a humble atmosphere of devotion . <3

Well it would seem the Col. may have some insight into your reality LT.

Hope it stayed that way, as alot us had to deal with some of those as you mentioned that were not so warming to us returning home. I hope when and if they ever returned from their turn being in-country they had a change of attitude.

A long drive down from the SFO area in a GTO, in a “normal” situation would have been a blast !! I know because I’ve done it but not in a GTO !!

Reporting in to an unknown situation once again must have been harder on your wife I would think, as they want to set up house ASAP.

Great chapter, looking forward to the next.

SEMPER Fi

Well, SgtBobD, a retromod GTO maybe…but those cars of that era, what a mess to keep running and fuel up all the time.

We have come so far. My old hot GTO would not be able to outrun a Honda today.

Semper fi,

Jim

Loved this chapter! Sorry you have to give up the GTO but “Happy wife, happy life.” One question. You wrote: “He’s got the purple heart,” the Colonel said, putting some anger into his tone, “and he’s wearing five decorations for combat valor…” I’m not familiar with the Marine Corps’ awards. What were the five decorations for combat valor on your uniform?

…and the answer is???

Captain my captain, I don’t reveal stuff ahead of time that is due to be part of the story

and my decorations are part of the story as it goes on in a fashion I want to have impact within the telling of the story.

You were a captain in the Special Forces. You know or can access the chart of decorations, which are pretty much the same,

with a few differences among all the services.

Appreciate your interest and the compliment you pay me in wanting to know more.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thank you, Sir, for another installment of your story.

God Bless!

You are most welcome Walter. Glad you are still along for the ride…

Semper fi,

Jim

WoW !!! James ( LT ) I know the Marines was/is different from the Army, but WoW I am so glad God interviewed in Your life so many times.

Well it looks as though You have lots to catch up on and recover from. I know the decision to part with the GTO was not easy, but You performed many tasks that were not easy. You have me amped up now for You’re next installment. PS what did it take to make 1st LT seems that would have been in order with all You went through.

God Bless Salute George

Making 1st LT was not the problem. It was automatic back then after around 12 months service, because they were going through lieutenants that fast. My serial number is 0104358. That means that I was

the 104,358th LT to never get his bars since the beginning of the Corps. Rare territory all by itself. The problem was having the promotion catch up with me in paperwork. My pay in the Nam was delayed four months

and that made life hell for my wife. I would not get nt official 1st LT notification for some time after being at Pendleton. Computers were in their infancy in those late days of the sixties and early ones of the seventies. Thanks for the kind comments

and reading the stuff.

Semper fi,

Jim

Geez, went does it get easier for you LT. Life just seems to keep handing you crap when it should be sugar, Thanks for the new chapter, keep it up, Semper Fi sir!

Finally, things seem to be going better for you and its been a long time coming. Great read with my morning coffee. Thank you!

One correction stood out though. When you were buttoning yourself back up in the Colonel’s office it says “bottoming” when it should say buttoning.

Find it hard to understand why some treated you so bad, especially your fellow Marines. I’m guessing they never were in Viet Nam. How long did you stay active duty?

The story continues Pete and that will all be covered as we proceed.

I was told that the books after Thirty Days should have less of an influence from the wartime experiences and I thought about that

for a bit.

My son told me to continue, as those years following had everything to do with what happened to me and my life and so many around me.

My son also said, when I indicated that the war had affected almost everything I did for the rest of my life, that I had yet to include those things were deeply effected by me. Interesting.

I don’t really stop and look at life that way.

Thanks for the interesting note.

Most of the people I served with following the war had not been to the war, or, if they had, had not been in combat. The combat Marines were very few and far between. Those Marines were totally cool.

Semper fi,

Jim

Things haven’t changed a lot. As you know both my MArines Sons served in Combat. One was in a reserve unit so when he returned home and got reassigned to a new Reserve Unit there were many long timers that had never seen combat so there was some ill will that this young non com had more ribbons than they did.

So very true, about the decorations, and so hard to accommodate back then, or even now.

We are still so very small as human beings developing…and way too competitive.

Semper fi,

Jim

LT you are so right! Combat changes you forever! It’s been 50 years since I left Vietnam but I still have “Vietnam” habits. I sit so I can watch the entrance (and that is non negotiable). I still watch my 6. I have a civilian legal unit one I carry with me when I’m out in the field. I have a fully stocked trauma bag in my pickup. I still react badly to loud unexpected noises. The 4th of July is a bitch. My late wife always said “He lived through it and now I live with it.” She learned the hard way not to grab me to wake me up. We all adjust and find a way to carry on with our lives. Welcome home Bro. Glad you made it back!

I’m enjoying every one of the chapters as they come out.

The amazing thing is, Terry, that we don’t really come back. Not as the men we were before.

We come back alright, but we come back different. So different that only by a very hard forcing

of fake behavior do we fit in at all. As time goes by that fake behavior deteriorates and people

see the real creature inside. Some like it and respect it and some don’t. Rough game, this long

term behavior is all about.

Semper fi,

Jim

Boy just think if you had been able to keep the “GOAT” what you could get now? I still regreat selling my 56 T-BIRD!!!

And my wife thought it was terrible and tacky that Mickey Thompson had painted his signature across the dash board on the passenger side with mineral-based white paint.

Jeez.

Semper fi,

Jim

Welcome Back James. I have heard similar stories about uncompassionate treatment of wounded vets from Nam. You might expect that from civilians but not from the military.

This is one huge competition out here and that includes everyone, not just the military. If you rise high then you will likely fall without ever having to do a damned thing, unless you are very

careful about guarding those things you have excelled at. Marines especiall, at that time, and probably now, did not like other Marines who had higher decorations.

I didn’t make the system or understand it at the time, but it sure as hell cost me a lot of pain.

My medals today are in the basement of my home, inside a trunk, which is inside a concrete bunker. That’s where they’ll stay, along with the boxes they came with, the citations, and the rest of the letters and other junk that came with them. I am proud of them, don’t get me wrong. But I do not need any more pain.

Also, never forget that decorations are the opinion of what someone else thought they saw and assumed that you did…not necessarily actually what you did or why you were doing it. When you get the medal you then have to decide whether you want to spend your life living the likely ‘lie’ on the citation or tell the truth and be held in either contempt or laughed at.

As in the song lyrics from long ago…I don’t have time for the pain.

Semper fi,

Jim

wonderful writing. glad you are here to put pen to paper! carry on

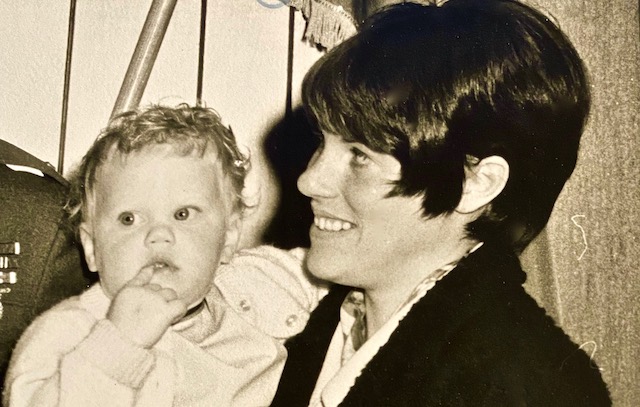

Great picture of Mary and Julie!

Thank you Dan

Jim

James, Great to hear the “welcome home” you received. They were few and far between – if at all.

Some minor editing suggestions follow:

Only four vehicles were present, none of the spaces occupied that had the letters; C.O., X.O., and 1st Sgt printed across the top of them.

Maybe reorder the words.

Only four vehicles were present occupying none of the spaces that had the letters; C.O., X.O., and 1st Sgt printed across the top of them.

Colonel’s, even regimental commanders

Plural not possessive

Colonels, even regimental commanders

because they are underarms.

Maybe separate “under” and “arms”

because they are under arms.

was to be encountered at personnel and forced to return to the 2/13

Maybe upper case “P” in personnel

was to be encountered at Personnel and forced to return to the 2/13

Multiple instances where personnel might be better capitalized.

When I found the personnel office

so much of the personnel office in Da Nang.

Fennessy had insisted that I get to personnel

maybe the fake aide, will call personnel.

I simply acknowledge the reporting

Maybe past tense for “acknowledge”

I simply acknowledged the reporting

so the forty-four dollars a month combat pay would be gone.

Are you sure about the $44?

Imminent Danger Pay: +$65 (Enlisted and Officers). Granted to personnel serving in a Combat Zone. Also known as “Combat Pay”.

I walked out to the GTO, reflecting on the simple fact that the woman’s sincere welcome and thanks were the most genuine I’d gotten from anyone outside of my wife and the guys who’d bought us lunch at the Thunderbird Restaurant at Rockaway Beach days before since I’d returned.

“since I’d returned” seems tacked on. Maybe drop it.

I walked out to the GTO, reflecting on the simple fact that the woman’s sincere welcome and thanks were the most genuine I’d gotten from anyone outside of my wife and the guys who’d bought us lunch at the Thunderbird Restaurant at Rockaway Beach days before.

The GTO was half empty of gas, and I’d been about nowhere in distance.

I had to reread this a few times to comprehend. Maybe substitute “traveled” for “been”

The GTO was half empty of gas, and I’d traveled about nowhere in distance.

“Read the orders,” I replied. The paperwork’s over on the kitchen counter. The orders say that I have to report in next week. This time I’ve been given is recuperative time and I’m taking all of it.”

Open quote before “The paperwork’s”

“Read the orders,” I replied. “The paperwork’s over on the kitchen counter. The orders say that I have to report in next week. This time I’ve been given is recuperative time and I’m taking all of it.”

_________________

Definitely some insights worth pondering:

“Or, had I changed?”

Oh yes! Big time. Didn’t we all.

“I’d underestimated her hatred for the car.”

That’s a huge step towards maturity and being a husband.

Blessings & Be Well