I opened my eyes to see Mary sitting next to the bed I was lying in, leaning forward, her face only inches from my own. The bed was tilted so I looked a bit down at her worried expression.

“Do you know where you are?” she asked, her expression serious and verbal delivery very studied and slow.

“San Clemente Hospital, where they brought me, I think,” I replied, looking over toward the room’s only window for verification but failing because the blinds covered every bit of the glass behind them.

I swallowed hard, my throat sore, and shook my head a little to try to clear my thoughts. My right arm was strapped to a board, an I.V. needle pierced the inside of that elbow although the bottle and other stuff had to be off somewhere behind me I knew. Mary was clutching my left hand, but not too tightly.

“Why are you asking?” I said, trying to think through the fuzzy feeling inside my head.

“You’ve been gone for two days,” she replied, looking into my eyes a bit too intently for my comfort.

“Where was I?” I said, realizing how stupid that had to sound. I was in a hospital bed following the fire. That much I knew. Where else could I possibly have been? I had no memory of being anywhere but on the roof then in the bush and finally inside a rocking and rolling ambulance probably on the way to where I was now.

“You were back in Vietnam,” Mary said, “I couldn’t make sense out of most of what you said. The super-heated air burned your lungs and esophagus, the doctor said so you’re on blood thinners and morphine for the pain.”

“Demerol,” I said, feeling a bit of discomfort for the first time. Talking was difficult. “Morphine makes me hallucinate but Demerol works fine, but I don’t think I need that at all. I’m not in that kind of pain.”

Her expression softened. I’d told her of my hallucinations when I was in the hospital at the Naval Hospital in Yokosuka. At least, possibly, she wouldn’t think I’d gone completely around the bend. I decided not to ask her about anything I’d said during the past two-day period as I’d hear about it soon enough if it were bad enough.

“How do I get out of here?” I asked, sighing deeply.

I had things that simply wouldn’t wait. The agency and reporting in, however, that was done, proving I was fit to keep my job, at least temporarily on the police force, meeting with Bob Elwell, who’d found me a secretary named Alice, further examining the artifact that I couldn’t get out of my mind, now that I had my mind back, and finally, listening to the last tape to make sure it contained nothing even more potentially cataclysmic than the tapes that preceded it.

It took all day to process out of the hospital, with Dr. Forsch, the neatest doctor I’d run into so far in my life, and I’d met a few, telling me that I should stay longer, be on blood thinners longer and, barring that, stay in bed for a week in order not to strain my lungs and esophagus. I fended him off, happy that he hadn’t brought up anything about my mental state during the two preceding days before I ‘popped out,’ as my wife put it.

When we got to the Chevy, parked in the doctor’s parking lot, Mary actually opened the passenger door for me.

“Where’s Julie?” I asked,

“With Bozo at the house,” she replied. “Elwell stopped by so he’s babysitting. It’s a wonderful house. Thank you,” she went on, pulling out of the hospital parking lot and hitting the gas, “The house, getting me this car, which I love since it’s like driving a great gentle bear, and coming back. I thought I’d lost you again.”

“Thanks,” I murmured, wishing she’d slow down a bit.

The low grumbling burble of the dual exhausts was something she’d instantly taken to, even though she’d always hated similar sounds emitted by both the GTO of old and some of the police cars I brought home upon occasion. I stared toward the south, as she held the Caprice to eighty-five miles per hour.

I watched the scenery go by, most of it undeveloped land on both sides of the freeway. I’d survived another potentially life-taking encounter. I felt inside myself that I was going to be okay, but I didn’t feel good about the Chevy. My wife had driven the car while I was in the hospital and came to love it. It was not her car. I was relegated to the Volks and there was absolutely nothing I could say or do about that seemingly small adjustment to my life, except I’d been so looking forward to blasting around town and up and down the freeways in the Caprice. It was like the Marauder, but instead of the macho presentation, it was a total sleeper. A family car turned into a road monster and now turned back into a family sedan.

“You might want to slow down a bit, even though there’s no traffic,” I offered.

“The speedometer says forty-five,” she replied, pointing between the spokes on the wheel.

“That’s the tachometer, that little thing,” I said, trying not to laugh. “The speedometer is that long bar running from one side of the panel to the other.”

When we arrived at Lobos Marinos Gates’ department Marauder was parked in the driveway.

I got out after Mary parked the Caprice next to it. He opened his door and stepped out, making no move to come around the rough idling vehicle.

“He wants to see you right away, so you better get into uniform,” Gates said, lighting a cigarette and taking a few initial puffs before going on. “That little prick has it in for ex-Marines so watch yourself. I don’t think either one of us is long for this job.”

“Thanks,” I replied, not wanting to confirm or deny anything about the new Chief.

I needed the job, at least temporarily, not just for the money but because I wasn’t ready to leave the guys on the force, the beach patrol crew, or the association it gave me with the lifeguards, the pier, and all the rest of it.

I thanked the lieutenant, went inside, and moved around among the strewn pieces of furniture and boxes. Bob was there playing with Julie, as usual when he was there. Bozo sat on the tallest clothing box, seeming to enjoy his new quarters.

Before climbing into my uniform, I checked to make sure my shoe shine box was ok, and the canvas sack holding the tapes was under the bed. They were. I’d have to search around for the tape deck but I was sure it was somewhere among all the junk that had been placed in our main bedroom.

Mary was working in the kitchen. I let her know I had to report in. She kept working, a shrug of her shoulders letting me know she’d heard but was too busy to discuss anything.

I drove ‘my car,’ the Volks up to the station and parked in the back.

Getting out of the vehicle I made sure I was properly attired, with everything on my uniform exactly where it had to be for an inspection. I’d even swapped out the .44 Magnum for the .38 the department provided for approved police work.

I braced myself and then walked in through the department’s back door and straight to Pat Bowman’s office.

Her door was open, as usual, and she was in her normal position behind the desk facing the opening.

I could walk without limping and my posture was fully erect, unlike the many months I’d moved around hunched over from the stomach wounds just after coming home and getting out of those hospitals. Sitting was easier than standing but standing straight up sent a message of health, whereas asking to take a seat did just the opposite after what I’d just been through.

“You want to sit down?” Pat Bowman said, noticing that I’d looked at the two chairs that were positioned against the glass wall that sat in opposition to her desk’s door-facing spot.

I shook my head, waiting for the chief’s door to open up, the door that had never been closed when Murray was chief but there was a new play in town and it wasn’t a comedy or a feel-good drama kind of thing.

“That was an amazing thing you did,” Pat said, her usual smile growing to be even larger.

“Thanks,” I replied, not really wanting to talk about it until I found out what Gary Brown wanted from me or to do to me.

“You formed the Dwarfs, let me in and I’ve so loved that, plus you never gave up on those Marines, like everyone else did. All that other stuff in the war too. Your wife must be so proud of you.”

“Thanks, Pat,” I said, not knowing what to make out of all her praise.

I wasn’t used to hearing it from anyone. My wife said I simply moved too fast to allow anyone to do much of that. That veiled lie was another reason I loved her.

The Chief’s door opened, but Chief Brown wasn’t standing in or offering to welcome me. I looked at Pat with a frown. Pat nodded back toward the opening and then whispered up to me so quietly that I almost couldn’t make out what she said.

“Be careful with him. When you see him don’t react like you have a way of doing.”

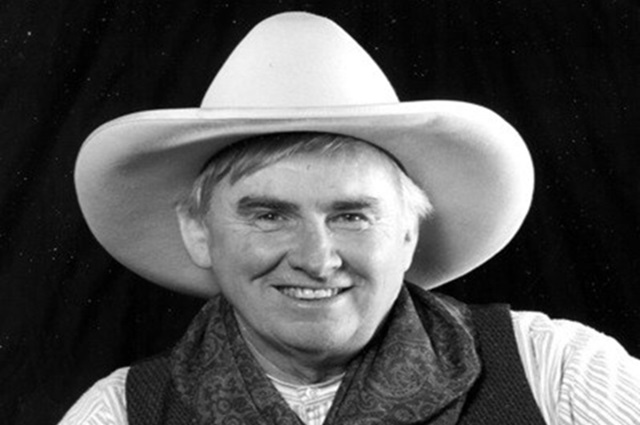

I walked through the door, wondering what Pat was getting at until I was inside the office. Chief Brown wasn’t smoking, and his feet were carefully tucked under his inherited desk. He sat in Paul’s position, his back ramrod straight with his torso leaning slightly forward, his chin placed firmly atop the interlaced fingers of both hands. I stopped to stand in front of his desk, looking over at him but keeping a straight face. I wanted to laugh so badly that I almost couldn’t stop myself.

The man was in full San Clemente police uniform, which was pretty extraordinary in of itself as he’d only been conditionally appointed only days before. It was the giant cowboy hat with a huge floppy brim that almost caused me to lose it.

“Jingles,” I wanted to say, as he looked for all the world like a thin miniature of Andy Devine, who played the sidekick to Guy Madison in the Wild Bill Hickok series on the many early morning television shows of my childhood. To make matters worse, he also wore a bandana that was held together under his chin with some sort of special pin I couldn’t quite make out. It was a six-pointed star but that was all I got.

“Close the door and sit,” he said, using his right index finger to point toward the only chair left in the office beside his own. He hadn’t moved his hands to do the pointing, which I also thought was odd.

I closed the door, as ordered, and then took the instructed seat, making my moves as smooth as possible. I wanted to give this caricature of a man as little reason to fire me as possible. Until the CIA officially came through I wanted to give this new very strange chief as little as I could to get rid of me.

“I got this job because of the kidnapped school kids in Chowchilla,” he said, surprising me. “But I was just the chief of a tiny department. We did nothing. The sheriffs out there, and the feds, did it all, but I got the credit.”

I stared at the man, who delivered his small speech while looking at the wall across the office in front of his desk, not at me. I waited a few seconds but said nothing, once again following Chuck Bartok and Tom Thorkelson’s sales advice.

“You climbed up on top of a house to do God knows what, the gas tank next door blew up, putting you in the hospital and stopping the progression of the fire. In other words, you did nothing except get the credit. We’re the same, except for that military crap. I wasn’t in the military, so I don’t give much of a damn about that.”

“I got to be chief,” he repeated, before turning his head to stare directly into my eyes. “You get to keep your job until it’s safe for me to send you on to something better. You are way too experienced and educated for this kind of thing and I think you know it. Officer Jordon, Sergeant Yeager, Gularte, and more of the officers, including firemen, are putting you up for the California Medal of Valor. It’s a big deal, to have one of my officers be given that award.”

I replied with the only phrase I could think of that might not set the seemingly unstable, or at least odd, man off, “Thank you, sir.”

“There’ll be no big celebration when they give you that medal, by the way, not here at the department, anyway. I don’t believe in that crap, but I don’t need any headaches from the department’s only duty hero ever. I know the power of that because it got me this job. What do you want?”

The man continued to stare at me, while I still fought to control the inner human demons that were threatening to express themselves and cause my demise. I had to get out of Brown’s presence as quickly as possible, I knew. He was potentially more capable of hurting me than even Haldeman had been, but I also knew I had to ask for something, only then would he feel satisfied that I was buying into the deal he was offering, even though he wasn’t really offering it to help me, but only himself.

“I’d like to wear my commander badge again, even though that’s kind of not real either.”

Brown nodded very slightly, looking away and then dropping his hand to grab a pen and write my request down, as it would take written annotation to remember the request. He paused and waited but didn’t look up or say anything. His fingers remained strangely still, holding the pen as if there was more writing to be done. I searched my mind for anything I could think of. I needed more, and then it came to me.

“I’d like you to promote Jim Gularte from the reserves to full-time as a Patrolman Two, I’d like not to have to attend any more meetings of any kind I don’t choose to until we agree that it’s time for me to retire. At that time I’d like to retire on disability instead of resigning and finally, I’d appreciate it if you bought a life insurance policy from me for both you and your wife.”

The chief stopped writing and looked across the top of the desk at me.

“Not my wife, she’s a Seventh-Day Adventist and won’t have it. How much will it cost in premium a year?”

I was shocked, as I had only added the life insurance as something to be denied, not to be purchased.

“About a hundred a month,” I said, no expression on my face.

The Chief wrote some more. “I’ll have the city add it to my benefit package, as long as you don’t want to be the beneficiary.”

I smiled, losing control for just a second.

“Oh, that’s kind of funny, isn’t it,” he said, smiling over at me, although his smile was more like that of a Japanese Samurai warrior.

It wasn’t really a smile so much as a very threatening grimace.

“That it?” he asked, putting his pen down and leaning back in the chair.

“When you get that medal the governor will be here for the event,” he said, finally removing the big hat and placing it carefully in front of him, before going on. “I want you to honor me at that luncheon, dinner, or whatever else they come up with.”

I still wanted to laugh but held myself together, looking intently at the man’s monster hat taking up fully a third of his desktop. Paying attention to every detail of the hat kept me from laughing out loud, which would be a disaster. I knew I was dealing with a kind of mental illness I’d never encountered before.

“Thank you, sir,” I said, getting to my feet, hoping against hope that I’d be able to avoid the man until I was retired, or whatever he arranged, at my departure.

“You’re gone when you get that medal, and don’t even give it a thought that you’ll be pinning that thing to your chest and showing up back at the department. I got diddly squat for the kidnapping mess.”

I almost replied that he’d been given the San Clemente Chief’s job but instead headed for the door. I wanted to stay and tell him all about the problems that were hidden when receiving a big decoration for valor but then remembered what I was dealing with.

As I walked by Pat’s desk she looked up, but her normal ebullient smile was reduced to a slight curving line across her lips. She shook her head gently. I kept going but understood. She was going to have a whole lot more difficulty in keeping her job than I’d have in losing mine.

When I was finally outside, standing in the parking lot next to the Volks I breathed in and out several times before getting inside and heading for home. The man had so rattled me that I drove to the old apartment instead of the new house at Lobos Marinos. There was already a family moving in. We’d finished moving out the day before. I sat watching for a while, amazed at how quickly property in San Clemente was sold or rented out if it was located anywhere near the ocean.

I headed for Lobos Marinos, but pulled off of Ola Vista to stop at Gularte’s place. His truck was there and the single entrance door was wide open. Before I could get the ignition turned off on the Volks he ran through the door and straight to my open window before I could get out.

“That little cretin’s promoted me to full-time!” he yelled, beating his chest with both fists. “Not only that, he’s jumped me right over Patrolman Three to Patrolman Two so I don’t have to do ride-along junk or go through the normally required probationary period. I can’t believe that such a weird creature, new to the job, might see the inherent talent and intellect of a man like me.”

I slowly got out of the Volks to stand at its side. Once again I was in full emotional and verbal suppression. To take credit for Gularte’s success would reduce his feelings of self-importance, which he didn’t have a lot of under almost any circumstances I’d witnessed so far in the time I’d known him. I had to say nothing about what had taken place and celebrate with him. I also didn’t thank him for writing me up, the real reason I’d stopped by, as Gularte was no dummy. He’d put two and two together, which he might eventually do anyway, but for the time being his life, and my own, was pretty good.

There was no time to go out and celebrate with Gularte. I wanted to return home and catch Elwell before he left. I knew nothing about Alice Ray, the woman Bob had ‘hired’ to be our assistant/secretary/whatever for the Mass Mutual District Office I was supposedly the manager of, now that Bartok was moving to Northern California. We hadn’t really discussed the artifact and the vital importance of keeping that secret a total secret for all of our protection.

When I got home Bob was already gone. Jules played among the boxes, making new play spaces using blankets and pillows that should have gone upstairs but there was only so much we could do in the day in getting unpacked.

I went upstairs to change. Once into my shorts and T-shirt, my usual San Clemente attire, I reached under the bed and pulled out the canvas sack. It took only a few minutes to open three boxes before I found the tape machine. There were certain things I was driven to do, and listening to the last tape was one of them. I knew I wasn’t in much shape to carry or lift boxes, or even unpack them as I’d had to sit and rest three times in searching for the tape deck.

The upstairs bathroom was a double bathroom for some reason or other. I went into the back one, closed the door, and locked myself in. There was a plug outlet by the small sink. I set the deck on the toilet after putting the lid down. It took only a minute or so to load the tape on the machine. I knelt. I’d listen to the tape as quickly as I could, and think about what was on it while I went back to work helping Mary finish the move-in.

The tape moved when I hit the play button. I adjusted the earphones trying to get more than a hissing sound out of them until the President’s voice could be heard. There was no question that the voice was his.

I listened intently for a few seconds before pulling the earphones abruptly from my head. His words had burned themselves into my brain so hotly that I knew I’d never forget them. I couldn’t go on. I shut the machine down and put it back inside its box with the tape still mounted on its flat playing surface. It took only seconds to replace the machine and the tape sack under our bed. I sat on the end of the bed thinking.

Mary climbed the stairs, Julie in tow, along with Mrs. Beasley. Bozo appeared atop the bed right next to me, standing before settling down to lie at the end of the unmade mattress next to me. Not characteristic of his behavior at all.

“You got tired and had to rest, didn’t you,” my wife accused.

I nodded. The words that I’d heard on the tape could not be repeated to her, or anyone else. I’d stopped the tape but there was more, and likely more that I didn’t want to hear. Richard Nixon’s words replayed in my mind as I watched my three favorite living beings, plus one not living, scamper around the bedroom.

“Kilgallen had to go and through time that work isn’t completed just yet. Are we together in that?”

One more trip to the confines of another hospital room, but you made it !!

Mary seems to be the perfect wife in so many ways, “but” take over that Chevy ?? Woah a step too far for me !! LOL

Great read James, will we ever get to hear the full info on the last tape? Sure hope so, but no doubt all in good time as is the writers prerogative 🙂

Semper Fi

SgtBob, yes you will get the full message on the tape and yes a lot of the mysteries will have resolutions.

Although when reporting on real life sequences it is sometimes difficult to provide final resolutions

many of them do resolve over time or get solved by work like I’ve been involved with. Thanks for the great

comment and your continued support.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thank you for the personal response, I feel privileged to be in on what happened straight from you.

I knew it had to be bad.

I joined the Patriot Guard Riders in 2013, we set up the Vietnam Wall in our local V.A. hospital in Kissimmee, FL. I was there every day for 2 weeks, helping the vets find their buddy’s names with our computer, then showing them on the wall itself. Even though it was much smaller than the actual wall in D.C., it had the same impact on them, most had never been to D.C.. When they came up to the table, they were just like a regular person, but when they found and saw the name(s) on the wall, they changed, I could see it and feel it. I would just go back to the table, most come back as we would print out any info we had and give it to them. When it was slow, I looked in the data base for any clue as to what happened and found nothing, which now makes sense.

I wasn’t in VN and have no idea what it was like for anybody that was there. I served from ’75-’82, 4 years USAF and 3 in the Army NG in Fl. 28 years as a fireman. I don’t know if I have the right to say this, but I don’t believe the blame falls on you. You were in a place and a position of authority that should have been under the control of more experienced people and of higher rank, none of which was by your choosing or design. You did everything you could with what you had. Those above you dropped the ball, who knows why, I sure don’t. My troops took great care of us FNG’s, most had served in VN as USAF firemen.

Not that I have anyone to tell, but mums the word. I can’t help but think if the Gunney had at least talked to you, even if it was an ass chewing, it might have helped you in some way deal with all of this. I want to thank you for sharing your life with me and all of us, I’m certain it has helped many you have felt like they were the only ones that had horrific things happen to them. I hope for peace of mind for all who need it. Thanks again Lt.

A great read LT. Awaiting the next installation.

Thanks Alan, I am working on the chapter today and on into the weekend. Look for it by Wednesday of next week,

and thanks for wanting to read it…

Semper fi,

Jim

My boss had a high school education and no military experience. I was a college graduate in engineering and a Vietnam veteran. He was jealous that his boss the VP of Operations wanted me to work for him half of the time. That high school boss showed itself in him thinking that I wanted his job which was as far from the truth as possible. He did everything he could to make my life unbearable. I ended up telling the VP that I was quitting if I had to work under that guy. The VP said that he didn’t want me to quit and that I could work directly for him. That was like going from hell to heaven.

You certainly use elements of your own past to write the truth, Cary. The city of San Clemente with Murray as Chief was a wonder.

The City of San Clemente under Brown was horrid. The sheriffs eventually took over the police department and that was lousy too.

Brown went on to become chief of other larger places because, well, those were the times. Thanks for the observations

and that truth…

Semper fi,

Jim

Jealousy from your boss can be a bitch!! Been there, done that. It makes you miserable.

Yes, I have to agree. There are plenty of ‘them’ around, like the battalion commander of my battalion in the Nam or the clown

at Treasure Island, the commander at the Civil Affairs group and so many more. Haldeman was all of that. thanks again, Cary,

Semper fi

Jim

Ha ! The Chief was never mentioned in the childrens kidnapping at Chowchilla that I could ever find any reference to. So it goes to show his attitude to being overshadowed by anyone who displayed any kind of initiative or outright devotion to duty re: heroism . Him giving into you while retaining an obviously chickenshit ” prominent ” role in what happened says it all . Hopefully his tenure as Chief didn’t last long and a real leader once again emerged from the ranks of the department .

The problem with Gary Brown was his total lack of any formal education and the simple mistake wherein he could

make himself the hero of Chowchilla to other law enforcement bodies. The media didn’t notice him but others did

including San Clemente’s city council of the time. It wasn’t that Gary was dumb, it was that he hated others who

seemingly outperformed him…and that very much included me.

Semper fi,

Jim

James,

Blessings & Be Well

Thanks DanC, for the edits, suggestions and the compliments…not to mention well wishes!

Semper fi, your friend,

Jim

Jim,

Bravo on the newest chapter!

Incredible and unexpected twists in the story!

It brought an audible chuckle when you discovered Mary thought the new beefed-up car was HERS! But you can still cruise around in the sexy VW bug.

Showing your wife where the speedometer was…

So flustered you drove home to the old former residence…

Plus, a new chief that was the spitting image of Andy Divine…

So thankful the propone blast did not kill you. That would have made the writing of your books and the reaching of thousands of readers and impacting their lives impossible.

The new chief sounds like a mess. You should be thankful you are on the way out of the police force there and will not have to be there long and have to dread working for the new head case.

Dorothy Kilgallen…?

That one came from way out in left field. Not expecting that.

Thanks for the newest ‘present’, and I will be anxiously awaiting the next ‘present’ in about a week.

Keep enlightening us…

I am sure you must have had some thoughts and theories of where these tapes came from…was it some of Nixon’s own tapes that somebody purloined? Or were THESE secret tapes–now in YOUR possession–secretly recorded by someone else (with their own ulterior and nefarious motives) without Nixon’s knowledge? How would they have come into the possession of the shady character who gave them to you? Why would he have stored them in the frunk of his irresponsible son’s car?

Wishing you the best, Sir.

THE WALTER DUKE: Man, my friend, you certainly can cover a lot of ground in one comment.

Mary’s ‘stealing’ of the Caprice was a classic, as was the car. Wish I’d been able to keep it through the years

Lasted a lot longer because she drove it most of the time. So much stuff came out of left field, as you describe it

during that brief period when I worked with the Western White House. Makes me wonder just how weird the current

situation is in D.C., although because of my time in the agency I know it’s got to be beyond strange most of the time.

Gary Brown was a piece of work, no question and diffcult to work with…to the extreme.

Thanks for the usual great comment.

Your friend,

Jim

About 15 years ago, I was living in Murrietta, California. It is located just over the hills from Camp Pendleton. The city probably did not even exist when you were there. There are some interesting roads up in those hills. I had an old Corvette with a brand new 383 stoker engine, and my wife was driving it for the first time. She said: “It sure seems like we are going faster than 30”. I pointed out that she was looking at the tach. I couldn’t help but smile when I read that you had said the same thing.

When I was a kid, my grandmother lived just down the road. I spent a lot of time with her, and she loved to watch the quiz shows. I remember Dorothy Kilgallen as being a frequent panelist. I never imagined that I would be reading about her 70 years later.

I am eagerly waiting for the next installment.

Randy, funny how real life situations can be repeated in other places at other times.

Illigallen was brilliant, like a lot of those earlier guests on that talk show.

Thanks for the great comment and sharing some of your own life and experience on this site with the rest of us.

Semper fi,

Jim

Well, last chapter, you went from the frying pan into the fire, literally.

Now your demons are continuing to vex you.

To paraphrase another common saying, “no rest for the wicked”

Keep up the good work Jim.

When you work in and around whaat are called ‘first responders’ there is stuff that can simply come out of

seeming nowhere. Then you have to improvise if it’s not something you or others around you, might have prepared for.

Sometimes firemen have to act like cops and sometimes the reverse is also true. Thanks for the compliment and the

encouragement.

Semper fi,

Jim

As usual, Jim, you captured my attention from start to finish. You have really developed as a writer. Didn’t even see any obvious editing to do!

The new Police Chief fits the description of many I’ve seen over the years. And almost always, it was barely possible to conceal my humorous thoughts – who the H— failed to see this idiot’s ego? Captain of my very small (4-man + me the armorer, the only one who had been to both LE Academy and Highway Patrol Academy) police department of a 1,000-person town. He pinned FIVE stars to his collar! He was also well over 300 lb., having broken the scale at the feed store.

Please, as requested previously, write faster! That neck surgery reminds me daily that I ain’t a-gonna live forever!

Stop it Craig. Just when you are making me smile in the writing of your comment then I am dragged back to worrying about your

continuance on the planet. I’ve lost so many, not that that counts toward much of anything accept realizing grief is not an emotion

that gets better over time or with the number of times you go with, not through, it.

Thanks, for the great comment and the compliments!

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

well James your writing continues to approve with each chapter you’re setting the bar very high and that’s delightful to watch and it creates a lot of suspense

there is a lot to uncover in this starting with your recovering from once again another injury if you’re anything like me once you cross 70 those old aches and pains come back in spades

i’d like to start with the crazy San Clemente chief obviously he’s a Saigon warrior type that is running a large mahogany desk however I do like that he wanted you to get the metal that he listened to you about Galardi and that you’re going to get an insurance sale out of it not all bad but obviously the guy is a dick but you shouldn’t have to put up with that for too long but you really held your own and didn’t lose it I have been in situations where I’ve been both side of the equation in my batting average is probably about 50-50 I’d like to discuss with you what you think yours might be LOL

not listening to the tape and sure hearing the horror you expressed through your writing was interesting when I finally got to the last sentence then it hit me

I remember Dorothy Kilgallon from what’s my line and my mother talking about her columns and she was one of the first two of course challenge the war in commission and the next thing you know she’s gone in somewhat mysterious circumstances for a woman at the time who was about 55?

so it’s clear there’s an association to JFK and I remember reading in a lot of the JFK books I have read over the year that there were people that pointed out her strange demise and her contact with Ruby and Ruby alone is another issue we must talk about sometime

it is clear from your description of listening to the tape and the way you describe your own behavior afterwards that it had a major impact on you and that is something that probably is with you to this day

my only disappointment in the last couple of chapters as that you have not at all and perhaps you can’t for legal and/or other reasons revealed much about any response you heard saw felt from the Nixon crew that was in the western White House Haldeman airman and all the other Hitler youth but we kind of all know that story and I can’t wait till we have lunch sometime soon

Keep up the great work

Thanks Sir Richard! Your in depth analysis plus your observations from your observations of what’s contained in the work.

A simple story complexly told…some might say, but certainly not you. Thanks for the time your take and the writing you do

yourself to make my work appear better. I much appreciate that, as you know.

Thank you, my friend,

and Semper fi,

Jim

Keeps getting more interesting. My Dad was allergic to Demerol. Went in for major experimental surgery and almost died. They had to put him on Morphine. He told me about the dreams (hallucinations) messed with your mind because it was always real places and situations that stretched reality in a demented way. Always had to stay an extra week for them to wean him off it after any procedure. Looking forward to the next chapter of your life!

My hallucinations were both frightful and entertaining, depending…had a monster ‘blob’ under my bed nobody else could see, of course.

Had people walking by in the hall but there was no hall as I was in ICU.

That kind of thing. Thanks for the comment and your own experience and your dad’s too.

Semper fi,

Jim

The first tape you listened too had something to do with the Texas book depository the next day on Fox a CIA guy from that time said they owned it. The next tape you listened too had Jackie talking to Nixon about the government killing her husband, the next day on Fox Robert Kennedy was on claiming the government killed his uncle and his father ,now the name Kilgalin comes up and she was on whats my line?I have forgotten what happened to her but im gonna be looking at Fox to see if it comes up. The democrat party has fallen out of love with the Kennedys and will never give him a chance.

Kilgallen died sitting up in her bed with a glass of wine half-filled on the side table.

Her hotel room was perfectly neat and tidy. Her toxicology at 52 years of age showed the wine and some barbiturates in her system.

That was given as the cause of her death.

Weather she died because of drugs ingested by others or herself will never be known.

All of her writing materials were missing from the room…supposedly never there in the first place, but the woman wrote non-stop so go figure.

Thanks for the interesting comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Wlkopedia didn’t really help in explaining that (by the way I think that is spelled wrong)? I thought your explanation of Demerol vs Morphine upon returning from the dead said you were Alive! “Very interesting”!

Colonel, you’re down there in Florida right now roaming around with a population that combs the beaches for jellyfish, so they

can consume the stingers and get their memories of youth back. Youth being back when they were eighty years old. At lest I did hear there

was some medicine for dementia based on jelly fish stuff. Hope you are having a wonderful time.

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

How people handle & harness the adrenaline rush in tight situations is telling. Kudos to you & the actions you took in that fire not thinking about your on safety. recall being on perimeter guard duty & they came around handing out extra ammo in anticipation of an attack. The obese guy in bunker w/me started quivering like a bowl of jelly & squatted down in the corner & wouldn’t get up. I had to restrain the urge to bash his head in.

The portion of the tape you reveal about Kilgallen adds substance to the conspiracy theories surrounding her death. What’s in the test of the tape? Did you listen to the rest of it? Left us hanging again!

For some reason this chapter showed up on facebook before your email notification.

Phil, Chuck sends the email out while I put up the Facebook stuff myself on all seven Facebook sites and LinkedIN. Sometimes I precede him

in that the chapter is up on the site first before the email is sent out. Thanks for the in depth analysis and accurate comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

I had forgotten about the untimely death of Dorothy Kilgallen. Now I’m going to have to read her book. Also James I just read that a movie about her life is in the works. Another compelling chapter my friend! Semper Fi!

Maybe Oliver Stone is making the movie about Kilgallen…at least I hope so.

/So many true patriots have paid these kind of prices for being so true…while

the cretins of the world, including inside the USA, continue to hold power by

killing them or dishonoring them. Thanks for the supportive comment…more to come.

Semper fi,

Jim

I wish my memory was good enough to keep all the pieces of this epic story straight. I have had to read three or four other books and historys because of questions I had about this time. I was shocked to hear that Kissinger was looking for places to “hide” the money (I trust more on that line may be revealed in the future)

I am totally blown away by the last line of this chapter. I just remember Nixon saying:: “I am not a crook.”

Now, I wonder who we can really trust? You, me, Chuck and ??

John, world leaders kill people all the time…sometimes on purpose and other times by accident.

Collateral damage, so to speak.

The most common comment I ever got when I was out attending the writer’s conference circuit was about people coming forward to say that they never lived and how much pain it had caused them to always tell the truth.

They were lying. Most truths about people are told by other people.

“I confess he did it” kind of thing.

Anthropologists once theorized that the spoken word was not invented to communicate facts. It was invented to cover actions.

And so, we have the mass media of today, and politicians and so many more, shaping the future by lying about the present and past. Great comment and appreciate the compliment and trust of you writing it.

Semper fi,

Jim

“ stay I bed for a weak” s/b in bed for a week

Time travel too? WOW!

Thanks BigG for the help and the compliment too…

Semper fi,

Jim

Tom, as you know by now, I answered this call with a rather extensive email in depth that I didn’t want to put on here.

What you have written I placed on Facebook, as it is so meaningful and caring.

Thanks doesn’t really speak deeply enough.

as a word.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, I’m completely blindsided by Mary’s claiming dibs on the Chevy.

You go, girl.

There’s two items in this chapter that may have already been mentioned in previous chapters. I’ll do some checking and post another comment if I find a discrepancy.

Note my suggestion on numerical order of Patrolman rank.

Andy Devine was “Jingles” in another TV series – not with Roy Rogers.

The death of Dorothy Kilgallen is suspicious as she was investigating the assassination of JFK. “The Reporter Who Knew Too Much” covers some of that.

Chapter heading is “Volume Two, Chapter II” maybe change to “Volume Four”

Change chapter order on home page to start with Chapter I

I’d like to see comment count under chapter header on home page.

Some minor editing suggestions follow:

barring that, stay I bed for a weak in order not to strain

“in” rather than “I”

“week” rather than “weak”

barring that, stay in bed for a week in order not to strain

got to the Chevy, parked in the doctor’s parking, Mary

Maybe add “lot” after “parking”

got to the Chevy, parked in the doctor’s parking lot, Mary

arrived at Lobos Marinos there the Gate’s department Marauder was parked

Drop “there the”

“Gates'” instead of “Gate’s”

arrived at Lobos Marinos Gates’ department Marauder was parked

checked to make sure my shoe shine box

And the canvas sack holding the tapes

One sentence instead of two. Lower case “a” in “and”

checked to make sure my shoe shine box and the canvas sack holding the tapes

Pat Bowman said, noticing that I’d look at the two chairs

Maybe “looked” rather than “look”

Pat Bowman said, noticing that I’d looked at the two chairs

My wife said I simply moved to fast to allow anyone

“too” instead of “to” before “fast”

My wife said I simply moved too fast to allow anyone

“Jingles,” I wanted to say, as he looked for all the world like a thin miniature of Andy Devine, who played the sidekick to Roy Rodgers

Google says Andy Devine was “Cookie” when paired with Roy Rogers.

“Jingles” was used when in the series “The Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok”

“Cookie,” I wanted to say, as he looked for all the world like a thin miniature of Andy Devine, who played the sidekick to Roy Rodgers

I wanted to give the caricature of man as little reason to fire me

Maybe “this” instead of “the” before “caricature”

Maybe add “a” before “man”

I wanted to give this caricature of a man as little reason to fire me

‘You get to keep your job

Open quotes

“You get to keep your job

It’s a big deal, to have one of my officers be given that award.

Close quotes

It’s a big deal, to have one of my officers be given that award.”

Jim Gularte from the reserves to full-time as a Patrolman two

Maybe capitalize “Two” as it is a rank.

Jim Gularte from the reserves to full-time as a Patrolman Two

I got diddly squat for the kidnapping mess.

Close quotes

I got diddly squat for the kidnapping mess.”

standing in the parking lot next to the Volks breathed in and out several times

Add “I” before “breathed”

standing in the parking lot next to the Volks I breathed in and out several times

he’s jumped me right over Patrollman three to Patrolman two so I don’t have to do ride-along

“Patrolman” rather than “Patrollman”

/LAPD ranks Patrol Officer from one to three with one lowest. Like military rank E-1, E-2, E-3. I’m suggesting change this sentence to “over Patrolman One” LAPD uses Roman numerals – in this case maybe better to use written numbers. Capitalize numbers.

he’s jumped me right over Patrolman One to Patrolman Two so I don’t have to do ride-along

for the district office I was supposedly the district manager of, now that Bartok moved North

“district” twice. Maybe drop “district” before “manager”

Lower case “north”

for the district office I was supposedly the manager of, now that Bartok moved north

Richard Nixon’s words I replayed in my mind

Maybe drop “I” before “replayed”

Richard Nixon’s words replayed in my mind

I watched my three favorite living beings, and one not living

Maybe “plus” instead of “and” before “one”

I watched my three favorite living beings, plus one not living

Blessings & Be Well

Thanks a million, as usual Dan. Everything fixed. Mary would let me drive the Chevy from time to time but under strict

supervision. Thanks for the comments, the compliments and the hard work on all our behalf.

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim