It was too early to do much of anything but head over to Galloways, the place that was growing to become the one thing I might miss the most when we finally made our geographic move.

Despite my high regard for the man, my conversation with Herbert had been discomforting. The things he left me with invariably made me feel more exposed, less secure and many times befuddled. How could anyone have confidence in anything I might do with whatever was dumped into my hands or ‘area of operations’ as Herbert referred to it? Operations was a big word in the CIA because it referred to that small portion of the Agency with the mission to go out into the world using HUMINT. Those were the letters used to describe who and what I was taking up with, and it wasn’t a voluntary part of the CIA. You were picked, selected, ordered, or simply found yourself to be one of them. Humint was a word pronounced as a word and not using individual letters. I had to handle the artifact and get that ready to be moved, as well as confront Paul so he didn’t live the rest of his life wondering when I might be coming to extract a price I never intended to extract.

I got to Galloways driving the Volks but thinking about the Ferrari and wondering whether it was actually a great thing to have driven that dream machine or would it have been better to never have driven it. The Volks felt like it was held together by cardboard, baling wire, and a bit of epoxy here and there…all painted over in bright red.

Nobody was there, except Lorraine and her husband, Tom, only discernable because of the noise he generated doing whatever he was doing to start their day.

I sat in my special chair at my special table. I’d miss both of those. Lorraine poured the coffee after setting the white porcelain cup and saucer into place atop the table with two slight tumbling whacks and then poured, all in one flowing motion using both hands.

“I owe you some money and we don’t have any prospects right now,” she whispered into my left ear.

I wanted to tell her that she owed me nothing but stopped myself. Knowing Lorraine, that just wouldn’t fly. There was no way she was taking money as a gift from me no matter what the circumstance. Her sense of independence was simply too strong, and I knew it.

“We’ll find another prospect soon and your credit is good,” I replied, not whispering because the was no one else there. I realized then that Lorraine was whispering to keep her husband from hearing, even though she’d indicated earlier that the money was going to him.

“We’ll talk at the first of the month,” I whispered, sipping my coffee and looking out the window.

What Lorraine might or might not owe me, a number I couldn’t come up with, in my mind, was of so little significance compared to the rest that I didn’t want to spend any time thinking about it. The money was very important to her though and part of what I had to do was make her believe it was important to me too. Lorraine was one of the Dwarfs, the only real group of people I could legitimately admit to myself that I was the leader of. I lead none of the beach patrol, the department, the Western White House things, and people. But the Dwarfs were different, even though I had almost nothing more to offer them.

Lorraine disappeared for a few minutes to the back, and I breathed a sigh of relief, but too soon. In seconds she was back.

“You didn’t come in wearing your new medal?” she said, with a great smile.

Tom eased into the room but didn’t come over. The medal subject had been discussed between them.

“Ah, no,” I replied, thinking fast. “The medal is up at the department. They’ll probably put it up on a wall in the squad bay, or something like that,” I lied.

The story about the wearing of the ribbon and the rejection by the shift officers would never be told again outside of what I’d told my wife.

“I need to use the phone,” I said, getting up out of my chair.

Lorraine said nothing, as Mike Manning had walked in through the nearly always open side door. I greeted him warmly and headed toward the back of the restaurant. There was no privacy, but the cord attached to the phone was one of those very long ones. I stepped outside and pulled the door closed behind me.

Matt’s number was right where I’d put it. I dialed and waited. There was no answering machine at the other end. I promised myself that I’d hang up after the twelfth ring. I waited, impatiently. I’d learned from one of the few egghead communication types at the Western White House that the ring you heard on the phone when you called somebody was a sound generated by your phone. For any phone you might be calling the rings occurred on the receiving end but that was during the silences on the calling end. The information never seemed to have any purpose in knowing but it made me wait through the silence after the 12th ring on my end and Matt picked up, but then said nothing.

“Matt?” I asked, frowning, and waiting.

“Matt,” the voice said back, and the image of the man from his gruff voice came right back to me.

There was a silence before Matt spoke again.

“It’s your turn,” Matt said and then waited again.

It was a strange start to any relationship the man and I might have and I was beginning to regret ever having kept his number, much less relying on him.

“I have a package that I’ve got to move a distance, and that package is hyper-sensitive to any change in direction…and I mean absolutely any.”

“Sub-orbital or interplanetary?” Matt asked.

I was struck into silence. Did the man have extrasensory powers?

“It’s a problem of a fluidly changing mass of extreme proportions,” I replied, hoping neither Matt’s phone nor Galloways was bugged by anybody but the agency. The garage break-in was still fresh in my mind, and my discussion with Matt, if overheard, might confirm that I still had possession of the object.

“How big and how far?” Matt asked.

“Medium moving box with the mass of an elephant,” I replied, risking even more on someone I didn’t really know at all. “It’s going from 303 Lobos Marinos in San Clemente to 4416 Magnolia in Albuquerque.”

“Interesting problem,” Matt replied, before going silent for a bit.

I waited.

“Truck for transfer and then truck chained down to the flatbed car on a train.”

A six-by is the ticket, borrowed from the Army National Guard here and then returned to the Marine Corps in New Mexico. There are no real problems dealing with weight and mass using a train and it’s mostly a straight shot for a journey of that small distance.”

I realized that the man was everything I hadn’t even dared to hope for. I’d have never thought of the train. It went mostly straight with gentle curves and the six-by, being the main military truck was called that because it had six wheels where all six could be powered to drive the vehicle. Its load capacity was five tons. It would be perfect.

“Dates, times, access, and billing number,” Matt said.

“Billing number?” I asked, suddenly realizing that there might be a problem in using Matt’s services, brilliant or not.

“Payment for stuff, what do you have or what did they give you?”

“American Express?” I murmured, almost as if saying that was a joke.

“Love Amex,” Matt replied, rolling right on as if everyone might have an Amex card that was unlimited since no numbers or reasons for numbers were being discussed. “Twenty-four hours from one end to the other, just about and I need about the same to get everything ready. A bit extra to pull the thing out of San Clemente as there’s no loading stop for cargo, much less a six-by at the stop there. Call me, I’ll stand by.”

The phone went dead in my hand.

I hadn’t had a chance to ask what the word ‘access’ meant. Access to what, or for what? But there was time. I was beginning to believe we only had a few weeks left in San Clemente. Herbert hadn’t given me a date, but I knew he was merely sitting back and waiting for me to get ready. Another violent change of applied discipline from the Marine Corps where just about everyone below flag rank gets told what to do about everything all the time.

I took the phone back inside, curling up the long cord as I went. I joined Mike at the table, Lorraine having emptied and refilled my coffee as soon as I headed back into the place.

“The insurance business is eating up your time,” Mike remarked.

“Well, I guess you’re right since my next client is sitting right here.”

Mike craned around to see who else was there before it hit him.

“Not me,” he said, expressively. “I don’t have anybody to leave anything to and I’m not sure I’d care enough even if I did.”

“I’ve got to get over to the Sun Post office and get my hero picture taken but we’ll talk a little bit later,” I said, getting up and downing the too-hot coffee, one medium gulp at a time. “You like Galloways here, Lorraine and Tom, all the people we send to your store, the other help I’ve added to that, and a bit more?”

“Oh, real nice sales presentation,” Mike replied, derisively. “You threaten all your clients into buying, is that it?”

Lorraine walked up, getting ready to deliver another small pot of hot water so Mike could re-steep his used tea bag. She waited until I was ready to leave.

“Mike’s considering buying a policy and he’s probably open about discussing it with you.” I smiled at Mike as the last words came out, then turned and walked out the door. As I started it, I watched the heated exchange between Mike and Lorraine going on through the front windshield of the Volks.

Lorraine had taken my seat.

“You have no hope, you poor bastard,” I said to myself, before turning on the radio and hoping to catch an A Shau inspiration in song. I knew there was little question about Mike’s coming purchase of a policy and, in fact, I could guess just about what the premium would be.

I drove toward the Sun Post office, located along the main drag leading toward the Pacific Coast Highway, a direction I was going to be headed after Freddy Sweggles got done with me.

I put on my blue pinstripe, Western White House suit coat when I was parked on the street out in front of the place. Fred was waiting, having cleared his desk so I could sit at it and make believe we were in my office. I had the certificate folder under my arm when I walked in.

“Where’s the medal?” was the first question out of his mouth as he grabbed my free arm and guided me into the back where his desk was located. He cleared off a bunch of half-naked women in beach shots and he went to work setting up the camera and two lights.

“Let’s just go with the certificate,” I said, sitting down and unfolding the plastic holder. A piece of white stationery fell out of the folder onto his desk.

“What’s that,” he asked, working frantically to get the stuff for the shoot just right.

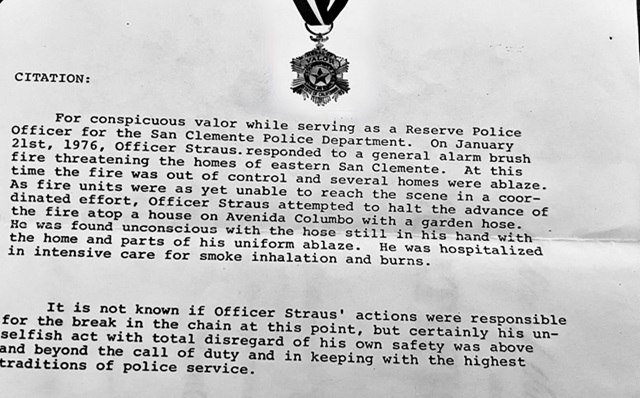

I picked up the typed sheet of paper. “It’s the citation,” I said, never having read the thing. It had been read, along with the citations of the other officers at the Redondo Beach Aviation High School event.

Fred grabbed the paper and read it through.

“This is great. This is the article I was supposed to read. This says you’re a great hero even if you might not deserve to be one. It’s pretty hilarious really.”

Fred was laughing but I frowned. The ‘turd’ part of the syndrome seemed to be starting pretty early, as I took the paper and read what I hadn’t even listened to at the ceremony.

I sat back and started laughing with Fred.

“You’re right, this is pretty funny. Maybe the guys up at the department would like me better if they read this.”

Fred stopped laughing. “Those guys don’t like you? That’s a little hard to believe. You know the president’s wife and have a nickname from her. You know Kissinger, Linda Ronstadt, and command the beach patrol. How can they possibly not like you?”

I knew immediately that I’d walked myself right into a lion’s den, and the small but potentially very damaging lion in front of me had to be diverted from a story that might kill my new career before it even got started.

“It’s not like that at all,” I said, dropping my laugh and smile. “We’re a very tight-knit department and brotherhood and they think the world of me. I’m sure that medal’s up there at the headquarters waiting to go into a shadowbox or something. After the shift last night, though, we held a choir practice and played poker. I won all the money and they’re mad about it.”

“Well, I can use this anyway,” Fred said, disappointment in his voice, “let me make a copy and then I’ll get the shot.”

Once we were done I took off the coat and headed home. I wasn’t going to appear in Dana Point in the White House rig when OP shorts and a Ralph Lauren short-sleeve would do. My New Balance 1300 shoes were unparalleled for my daily runs and simply for walking when my torso might be acting up a bit. Dr. Forche, my friend at the San Clemente Hospital complex told me that only a few years earlier, when I had my extensive bowel resections, the surgeons had yet to discover that the nerves in the intestines needed to be set against one another when rebuilding intestinal material, hence there would be occasional problems ‘down there’ until enough time for regrowth took place. I’d asked him how long and his answer was chilling.

“Longer than I have left.”

I turned on the radio, and hit the AM button, as San Clement was exactly 66 miles from L.A. north and 66 miles from San Diego south. FM didn’t do so well on most days with the hilly environment of the city’s location. Margaritaville came on and I smiled while I drove. A song about being righteous wherein the protagonist, the singer, goes from being right in the divorce to his being fully at fault as the song and story play out. So much of real life inside the lyrics of another song, written and played by some guy down in Mexico I didn’t know and very likely never would know.

The house was empty by the time I got there, which meant, since the Caprice was also in the driveway, that Mary and both kids had to have gone to the beach. Mary was amazing in so many ways, as I’d come to know. Down the cliff path she’d gone, carrying a newborn and accompanied by Julie, where they’d sun and play in the lapping waves until later in the day. My childhood was steeped in being around water of all kinds, but mainly the Pacific Ocean. I knew I was going to miss that part of living in New Mexico and I wondered how long it would take before I was pulled back toward that giant body of water that I could only hope would be waiting for my return.

I did a fast change and then stopped briefly to visit the artifact in its ‘hide in plain sight’ resting place. The slightly damaged box was secure although I didn’t open it to physically take in the artifact itself, as it was doubtful that anyone would open the container instead of simply taking the whole thing if that was what they wanted. The container was not so much a hiding place for the object but a safety feature, as well.

The trip to Dana Point took almost no time at all. Traffic was light and I’d decided to take Mary’s car as I was still trying to adjust to not being in a Ferrari anymore. Little Mardian played with my mind in a way that I had never expected nor would have assigned much importance to until the experience of driving that stunning automobile was over.

The Caprice was no match for that barely civilized race car carefully built to allow it to be driven on regular roads and highways, but it was a long way in size and performance from the Volks. Running north on the straight stretch into Dana Point I hit a hundred and twenty before sanity emerged and I shut myself down. Civilian roads were no place to drive like a maniac on any kind of regular basis. The police experiences had burned that in. Accidents were called just that because nobody intended for them to happen, and generally they happened because of either idiotic behavior, like my own, or unforeseen circumstances. Still, the trip made me feel better, although I wanted to make sure and get home before Mary got back. She didn’t like my taking her car, even when she wasn’t around. She never said why, but by doing a hundred and twenty when I did take it, however unknown to her, was very likely suspected. I liked the fact that she worried about me, as well as the time and effort she’d spent, so far, in reassembling me for a functional life again after the hell of Vietnam. I had to get her to Albuquerque so she could give her acceptance and final approval on the house. Her tacit approval was appreciated but I knew, after our years together, that she needed her tactile and physical presence in the place to make it her own.

I drove to the parking lot and put the Caprice in a slot as close to Richard’s boat as possible. I needed Richard for the move, nearly as much as I needed Matt, but not on the same level and not, even though I had known him so much longer, trusting him like I had so quickly come to trust Matt. I knew it was because Matt gave every appearance of wanting to be on my team, or of my never-ending search to be a member of my fictitious lost company that he knew nothing about. Richard was a player in the same game I was now in, but he was a player who’d already demonstrated several times that he was in the game for himself first, and me somewhere down what might be quite a lengthy list.

He came on deck without my having to jump down into the cockpit and knock on his expensive teak door.

“The hero comes aboard,” he said, with a big smile, “Almost like the Navy thing on ships when the coxswain at the helm yells out to anyone around, ‘the skipper is on the deck’.”

I nodded and sat down on the uncushioned edge of the cockpit. There was no use deprecating or trying to minimize the decoration. I’d learned the hard way that those getting that message from the ‘hero’ only reacted badly. Failing to properly show respect for a decoration was a complaint that was hard to argue with. Even taking the ribbon off my police uniform and then showing up to work without it would be seen that way. The hero turd syndrome just lying there waiting for conduct like that. Mary’s usual comment of wisdom, when I’d mentioned the experience was spot on.

“Just don’t go in and work the street again, since we’re leaving anyway. I think it was Lucy Ricardo who said in one of those I Love Lucy shows, ‘One of these days I’m going to leave these clowns.’”

I didn’t mention that the show was totally fiction, instead simply accepting her objective opinion about what to do as being the best course of action to follow.

“You need me for something?” Richard asked, going right to the heart of the reason I’d stopped to see him.

I filled him in on the coming move and as much about the details, leaving out the transportation and potential delivery of the object to either Los Alamos or Sandia Labs, and then stopped talking.

“I’m all in,” Richard replied, which surprised me, “Just let me know where and when you want me and how you want my help to be adjudicated.”

I hadn’t heard the word adjudicate since I’d been that officer for evaluating moving expense losses at Treasure Island.”

“Thanks,” I replied, about to go on before he spoke again.

“Herbert interviewed Paul and Paul’s at the drug facility waiting for you. I don’t think, for whatever reason, that Herbert was much comfort to him as Paul, before that, had little idea of just what kind of power structure you may be a part of.”

I sighed deeply. Paul had nothing to fear from me. At times I’d wondered if he was a plant placed there by the Agency but could never get past the part where I’d stopped by Straight Ahead only because I’d seen his lopsided and seemingly ridiculous sign for psychological services pasted near the entrance to the place. That was pure circumstance that nobody, not even the Agency, could arrange without going back in time.

“Alright,” I said. “I’ll go see him now.” I got up and turned to climb off the boat.

“Be careful, he’s a complete amateur, which means he may be armed.”

“What?” I said, my shock at such a comment registering fully in my tone.

“You carrying?” Richard asked.

Mr. Strauss, Sir,

After reading your works since sometime in the second 10 Days, I’m having a problem getting your most recent posts. I have been getting them for a long time in my email inbox, but Volume 4, chapter XIII is the last one that I got in this manner. I have been using a search engine to find your page and then getting a chapter that way, but now even that doesn’t seem to be working. Am I doing something wrong? Or maybe I missed a new sign up program? In any case, I hope that I will be able to get back to having the weekly chapters delivered to my email inbox. You’ve got me hooked on your life story and would like to be able to continue.

Keith thanks for the comment. According to our email server you are still subscribed and have been since 2019.

We can’t control how Comcast handles those emails. Have you white listed the email address jim@jamesstrauss.com?

Also Please check you spam folder. The image below shows how you are listed.

If you are not getting them, please also contact, Chuck Bartok

chuck@jamesstrauss.com

I just got back to reading the series and I don’t know if you can help me or not, but I got two posts for Chapter VII, one on 3-27 and the other on 4-4. I never got Chapter VIII. On 4-10 Chapter IX arrived. If it is possible to forward VIII That would be great, and I wouldn’t have to imagine what I missed.

jamesstrauss.com is the website. On the top of the front page you click on The Cowardly Lion, Volume Four, and then when that link comes up you scroll down and all the chapters to Volume IV are there. You don’t have to wait for the email as Chuck usually gets the chapter up the day before or sometimes even earlier. Thanks and sorry for the confusion.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thanks. I guess getting older made me not think about that.

Nah, you are cool. We can’t think of everything all the time…that was Sherlock Holmes and we know how

old and real he was.

Semper fi,

Jim

I did receive both emails but am tardy in my response. I enjoy reading the comments & your responses as well. Gives me a better understanding of what’s going on.

You must have a 6th sense about people to trust. The latest being calling Matt out of the blue to help in your latest quandary, a person you barely knew.

Enjoying the ride. Keep them coming.

Being young is to experiment and we do that with relationships as well as other things, as I am portraying.

Yes, I trusted many who I had not time to really get to know or test, but then it’s all such a vast learning project.

I won more than lost, which I attribute more to the innate goodness of man than to my ability to be a judge of such things.

My wife is better, and she helped a lot that way.

Thanks for the great comment and the compliment.

Semper fi,

Jim

when I had by* extensive bowel resections, the surgeons had yet to discover (my*)

Next step dump off the artifact and move on to your new life of adventure without medals !!

Trying to keep up James great chapter !!

Semper Fi

Would that life was so easy as dumping off anything back then.

Thanks for the thought and paying attention to the developing story in such detail.

Semper fi,

Jim

When I was a kid I used to daydream about doing daring things…after reading 30 Days and reading this book I am glad i live a simple uncomplicated life…they bust em and I fix em…(mining machinery)…that stuff donT argue, bitch, piss and moan, whine, or make any strange demands of me. Just weld it all back together and get it running again.

All that being said I am glad there was and still is folks like you that do the stuff you have done. There aint much more I can say other than thank you.

Popeye

Jay, an uncommon and well written comment for certain.

I love it when readers like you bring the rest of us in about they do and have done in life as well as the depth of thoughts provoked by the writing.

Much appreciate the thanks and the compliment of your writing it on this site.

Semper fi,

Jim

Having been a part of this from the beginning or at least the through the episodic version of Cowardly Lion, I am wondering this has corrupted my understanding of the whole… Reading the completed books; if that ever occurs will be an epiphany! But now I am encapsulated as a follower and can not wait for next week….

Colonel, you are just as great a man as you were flying double harness back in that A6 over the valley.

I don’t miss those days and so glad that I don’t have to miss you either.

Much appreciate having the friendship, trust and honor of your great friendship.

Thanks for the supporting and creatively fortification of a comment.

Semper fi, my great friend,

Jim

Jim,

Things are just blurringly racing by, requiring a supreme bit of simultaneous ‘multi-tasking’. For most folks, their idea of ‘multi-tasking’ is: sitting on the porch; drinking their morning, afternoon or evening coffee, or some other favorite beverage; noting the welcomed call of a bird, or owl; watching as an opossum has his/her head stuck in a plastic McD’s cup you’d left partially full of coke on your steps, happily slurping up the remainder, completely ignoring your presence or the light being shined on its face, as if saying “bug off” or some other adequate phrase; noticing the grass needs to be cut while thinking – “First thing tomorrow!” – Yes – “multi-tasking”.

While you, on the other hand, deal with: getting a medal; dealing with the “turd” syndrome; saying goodbye to folks who have meant something to you; changing to a new job, a new job just chocked full of unknowns; having to fool your wife about the new home in NM; moving to NM; turning over the alien object with little to no guidance; dealing with a guy who’s afraid you might want to make him ‘disappear’ after hitting on his wife, firmly believing you could indeed make him disappear; and on and on. Well, at least no opossum, though I think you’d enjoy the experience. Like I said earlier – ‘a supreme bit of simultaneous ‘multi-tasking’. Most folks would have just said “bug off” or end up institutionally confined. Just sayin’.

He_l, I had to have another cup of coffee just reading this. Oh, more comments to come.

Sincere regards my friend,

Doug

I read you comments in great depth, taking my time and then rereading a few more times.

You have an ability to reach inside and really hit points right on the head, time after time.

Thanks for taking your ‘coffee time’ to read, reflect and then pick up your own pen and

write straight from the shoulder and heart…

My day starts with a Danko smile…

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

Jim, Thank you for your kind words. One of the minor multi-tasking events (There may be more —- OK, there’s more.) I forgot to mention, deals with you becoming the father of a new addition to the family. Oh – how has The Cat responded?

And to be completely honest, my day starts with some words of thanks, a pee, some gas and making some coffee. Then taking out the puppy for a pee, some gas (Hopefully more than just gas.), some sniffing and seeing if there’s anything in the grass to eat or any four legged animal to eat, then back inside to drink some coffee and some more words of praise and thanks. Just sayin’.

Have a great day and regards to Mary on her Nationally recognized day, for the many things she does every day. I forgot – Does the NM home have a pool? If not, mmmm. Just a thought, as I reach my limit for TftD (Thoughts for the Day).

Regards my friend,

Doug

Thanks my friend, my last comment kind of said it but I missed the ‘reply’ button.

Your comment needed to be published though.

Semper fi,

My friend,

Jim

Lt, you have had a very complicated life and it comes out in your writing. I took a look at the poem that you sent out. I’m not the person you should ask to evaluate poetry. It appears to be sound, but don’t take my opinion to heart.

Sound poetry. You have a rather droll sense of humor and I love it.

Thanks for that and the evaluation of my life.

Semper fi,

Jim

Hello sir, yes I received the chapter, sorry for the long wait for my thoughts. Reading the comments was as enjoyable as the chapter! The “move seems ready to occur and with it a whole new story, keep it a going and Semper fi Lt!!

The comments on this site are extraordinary and unexpected.

When I started publishing my work this way, I never thought about the fact that the readers might be my equal in laying down their most

heartfelt and personal thoughts…

and then taking the risk of putting them up here for others

to read and possibly disagree with.

Thanks for that and what you wrote…

Semper fi,

Jim

You keep writing critiques like this Danko and I’m going to have to start paying you!

Thanks a million for the truly great interaction and your work on pouring through the pages.

Much appreciate that and your friendship.

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

Jim,

Thanks for another episode to whet our whistles.

A little confused about wo “Matt” was. But then I looked back on previous chapters and saw it was the guy on the military plane on your return trip form NM.

Maybe Lorraine is spending the money on something her husband knows nothing about?

Looking forward to the next chapter.

Wishing you well, James.

THE WALTER DUKE. Thanks for the apropos comment and the compliments.

Always neat to read what you glean out of the story and then comment on.

Semper fi,

My friend,

Jim

LT, as always another interesting chapter. I need to go back and catch up on some of the characters in this novel. I airways wondered about Paul being something other than portrayed. He has to be shitting bricks as he learned about power among people around him. Thanks for keeping us rolling along.

Unless you spell it out or actively display it in some other way, people generally don’t know or recognize the

power that may be in their presence…something I usually treasured, as the power I held, if unleashed might

not be fully under my control. That’s my wisdom of today, which was in the future back then and I had a lot

to learn about all of those things.

Thanks for the great comment,

Semper fi,

Jim

Not surprised at your reaction to the medal you received. You’re quite humble at heart, like many who have received awards for heroism. Lord knows you are deserving, and those of us who have been in the military usually recognize that. Personally, I would see a medal or ribbon and be a bit in awe of what you had been through. Many of us would have done the same in that given situation, many of us would not.

I do not envy your move to New Mexico. Being a Navy brat, as you were a Coast Guard one, I had my 55th birthday on the same day I moved into my 55th house. I’ve added only 8 more in the past 23 years. Filling out the forms for different clearances was always a pain – but retired fossils no longer have that chore.

Truly enjoying your autobiography. And wondering about that sphere if the train has to make a sudden stop…

Just as a primer toward future writing and the direction of my life back then; they don’t call New Mexico the land of enchantment for no reason at all.

Thanks for the usual meaningful and heartfelt response to my writing and since you didn’t mention it I’m going to continue feeling positive about your health and having you in my life, such as it is, for some time to come.

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim

the tale of shipping the artifact is dull but need in the story

Funny for Richard to ask if you were strapped.

the medal you and awards/ medals

the readons?

1. **Humility**: They may feel uncomfortable with the attention or recognition that comes with receiving an award and prefer to stay humble.

2. **Personal Values**: The award might conflict with their personal values or beliefs, making them reluctant to accept it.

3. **Imposter Syndrome**: They might feel like they don’t deserve the award or that their achievements are not significant enough to warrant such recognition.

4. **Pressure**: Accepting the award might come with additional responsibilities or expectations that they are not ready for or interested in.

5. **Privacy**: Some individuals value their privacy and prefer to stay out of the public eye, which can extend to declining awards or recognition.

6. **Political or Social Reasons**: They might decline the award due to political or social reasons, such as disagreement with the organization presenting the award or the values it represents.

Understanding the specific reason behind someone’s reluctance to receive an award often requires knowing more about their personal beliefs, values, and circumstances.

Do you remember the day i presented you the Order of the Cowardly Lion?

you cried

How about, simply, that other men who don’t have such decorations are not nice to the people who have

them in any private or substantive way? They say they are nice and they act that out under social

circumstance but down deep, they feel like they lost the competition or something and that the need

to bring the decorated person back to ‘reality.’ A reality that is deep down and dark. I don’t want to

go there and never did. I accommodate what I received but I sure as hell am not proud of how it all

really works through life. Decorations belong first in a shadow box, then in a suitcase and finally

in a trunk to be discovered by living people after the decorated guy or gal is safely dead. I support the

USA, the military, the United States Marine Corps and the people who went to the trouble of awarding the

decorations they did, but the rest of it? Trunk in the basement.

Semper fi, your friend,

Jim

I keep thinking about the Marine rat in the maze that chews his way diagonally to the cheese! You seem to be an artifact on your own.

Then we have apposing nerves is your large colon!

Paul could only exist in the SoCal 70s & the M1 tanks move…..

Beautiful

An artifact on my own…now that takes some thinking about. Little question that

I am a stranger in not only a strange land but an alien one as well.

Thanks for the usual penetrating and deep comment.

Semper fi, my great friend,

Jim

James, Interesting that Matt joined the team and came up with a solution. Good man to remember.

VW red may be konigsrot aka royal red. Loved mine.

Lorraine for the victory!

I’m waiting to see if you resign from the police force or if Chief Brown finds some excuse to dismiss you.

Some minor editing suggestions follow:

The things he left with invariably made me feel

Maybe add “me” after “left”

The things he left me with invariably made me feel

I got to Galloways’

Possessive apostrophe here. Just be consistent in whatever you choose.

another prospect soon and you’re credit is good

“your” possessive instead of “you’re”

another prospect soon and your credit is good

none of them did I lead

Maybe rephrase

I lead none of them.

sound generated by your phone

/sorta true/ actually a sound generated by your local telephone office

Matt’s phone nor Gallows was bugged by anybody

“Galloways” instead of “Gallows”

Matt’s phone nor Galloways was bugged by anybody

Truck for transfer and then chained down a truck to flatbed on the train

Maybe reword

Truck for transfer and then truck chained down to flatbed car on a train

the six-by, being the main military truck was called that because it had six wheels that all drove the vehicle and could carry six tons, although in reality it carried five

/basic design came in several sizes: 2-1/2 ton and 5 ton carrying capacity. Slang for 2-1/2 ton is deuce and a half (most common).

Six-by-six refers to the ability to engage all axles and have all wheels powered. Note also the rear wheels have dual tires – so ten tires total./ Maybe rewrite some:

the six-by, being the main military truck was called that because it had six wheels where all six could be powered to drive the vehicle. Its load capacity was five tons.

since my next client is sitting right here.

Close quotes

since my next client is sitting right here.”

getting up and down the too-hot coffee one medium gulp at a time

Maybe “downing” instead of “down”

getting up and downing the too-hot coffee one medium gulp at a time

clients into buying, is that it?

Close quotes

clients into buying, is that it?”

“

You have no hope, you poor bastard,”

Backspace to close gap

“You have no hope, you poor bastard,”

piece of white stationary fe-el out of the folder

“fell” rather than “fe-el”

piece of white stationary fell out of the folder

working frantically -to get the stuff for the shoot

Extra hyphen before “to” Drop

working frantically to get the stuff for the shoot

This is great, this is the article I was supposed to read

Two sentences.

Period after “great.”

Capitalize “This”

This is great. This is the article I was supposed to read.

when I had by extensive bowel resections

“my” instead of “by”

when I had my extensive bowel resections

FM didn’t do so well on most days and with the hilly environment

Drop “and”

FM didn’t do so well on most days with the hilly environment

The slightly damage box was secure

“damaged” instead of “damage”

The slightly damaged box was secure

simply taking the whole thing is that was what they wanted

“if”instead of “is”

simply taking the whole thing if that was what they wanted

trying to adjust not to being in a Ferrari anymore

Move “to” after “adjust”

trying to adjust to not being in a Ferrari anymore

doing a hundred and twenty in when I did take it

Drop “in”

doing a hundred and twenty when I did take it

trusting him like had so quickly come to trust Matt

Add “I” after “like”

trusting him like I had so quickly come to trust Matt

into the cockpit and now on his expensive teak door

“knock” instead of “now”

into the cockpit and knock on his expensive teak door

coxswain at the helm yells out to anyone around, “the skipper is on the deck.”

Maybe single quotes around coxswain at the helm yells out to anyone around, “the skipper is on the deck.”

And leave full quotes around Richard’s statement.

coxswain at the helm yells out to anyone around, ‘the skipper is on the deck.’”

Blessings & Be Well

As usual, my friend, tremendous help with editing the chapter and great comment too.

The 69 was called Poppy Red and the paint touch up was L64, I think. I’m sure its on the Internet

for real though. Maybe it was L65. Thanks ever so much for the help on this one.

Semper fi, my friend,

Jim