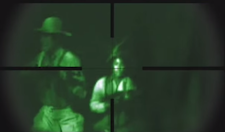

Zippo didn’t get back from retrieving the starlight scope from Rittenhouse until full dark. There’d been no fire from the hill. I’d registered our new position but not ordered a fire mission. I knew it wouldn’t be long. I wasn’t afraid of taking fire from a heavy machine gun nearly as much as I was from the prospect of the NVA attacking and penetrating our lines, or what might come of the obvious threat from First and Fourth platoons internally. By the time I moved to Zippo’s hooch to try out the scope, I realized my shaking hands were back. Longer than an M16, the scope weighed twice as much. It was like handling a thick length of sewer pipe with a big rubber grommet on one end. The night mist returned, combining with my repellent soaked hands to make the black metal hopelessly slippery. Handling the ungainly scope, in conjunction with my shaking, was nearly impossible. The case for it had to be bigger than Fusner’s radio. I wondered if the thing was worth the effort until Stevens flipped a switch and I pushed my eye into the rubber grommet and stared into the lens.

Green light everywhere. Shadows of green light in the distance. I knew I was seeing things in the dark that were impossible for a human eye to detect, but I couldn’t make them out. Everything moved too much and the scope seemed to be slowing things down. If I moved the scope at all it seemed to take part of a second for the green scene to catch up.

“You’ve got to prop it up on something,” Stevens said. “It came with a tripod but that got lost somewhere.”

I laid down on Zippo’s poncho cover and propped the ‘sewer pipe’ across the back of his pack. I pulled the scope and pack closer, and then stared at the jungle not far away. I knew it wasn’t far away because I’d seen it during the day, but I also knew because I was seeing it at night. The view was astounding. The wind wafted across the tips of different kinds of jungle growth. I watched, feeling like I was hypnotized. I could even see the moisture falling and blowing around in the air. It looked like rolling green mist. I watched the Gunny light a cigarette in his hooch twenty yards away. His lighter flared briefly, like a street light burning out. I saw every green feature of the Gunny’s face. Gazing through the scope took some of my fear away, and I didn’t want to stop looking through it.

“It works best across cleared areas,” Stevens said, “and tracers coming in make it impossible to see anything because it takes a while for the tubes, or whatever, to recover from bright lights.”

I pulled away from the addictive device. I noted that my hands had stopped shaking.

I pulled away from the addictive device. I noted that my hands had stopped shaking.

“What case does it come in?” I asked, wondering how much space on Zippo’s back it would take. I’d already decided that I never wanted the scope far from me at night if I could help it.

“Case?” Stevens said, “It straps to the outside of a pack with a sock on each end.”

“No case,” I replied, shaking my head. “Lost somewhere, no doubt.”

“Let’s move out,” I ordered. “We’re headed straight for the perimeter just short of the hill. Maybe we can use the scope to find the best way through the muck.”

“There’s a path not far from here,” Fusner pointed out, getting strapped into his radio rig.

Nguyen leaned out of the dark and whispered to Stevens.

“No path,” Stevens said. “We’ll break some trail south and come around along the western perimeter,” he went on. “Wouldn’t want to run into an ambush,” he finished.

I wasn’t sure about whether my team was looking out for me or for themselves, or both. But I appreciated it.

“When we get set in to observe, I want the scope out and operational, pointing behind us,” I ordered.

My team had picked up on the phony ambush routine, or seen it before, so I fully expected they’d understand what I was trying to do.

“Everyone’s got tracers now, sir,” Fusner said, standing nearby and ready to go. “The scope doesn’t work around tracers.”

“I’m not worried about anyone shooting,” I replied. “At least not until they find us. I want to see them coming first.”

Zippo carefully slipped two socks on the ends of the Starlight scope and slipped it over his shoulder. He’d found a rifle sling from somewhere. The heavy scope was like an invisible twig on his broad back. I noted that he carried a mostly empty pack in his right hand. We didn’t wear packs inside the wire, especially when we expected to engage the enemy. Without a deep foxhole to dive down into the only protection available from some threats was the ability to move.

Creeping through the brush was hard work, even with Stevens and Nguyen breaking trail in front of me. Fusner and Zippo followed up. If visible in daylight, I’m sure we resembled hunched over dirty lobsters as we crept around and then straight up to the perimeter.

“Who the fuck is at our six?” came back from up ahead.

We automatically slunk down into the mud on our hands and knees.

“Arty up,” Stevens half-whispered toward whoever manned the perimeter ahead of us.

“What do you think this is?” the voice hissed back. “Fucking officer country?”

I listened to the exchange, knowing that I was crazy and not caring. I wanted to take out an M33 grenade and lob it forward. That would take care of the problem. A craven need building inside me to do something about the flagrant insubordination and the lack of one shred of respect toward me was a basal force driving my emotions. I knew it, and what remained of my sanity made me hang on. Instead of replying or taking action I simply waited in silence. My normal role.

A form appeared from out of the nearly invisible mist.

“Over here,” the voice said.

The form moved back the way it’d come, and then away when Stevens and Nguyen settled in, their bodies pressed up against a beaten down hillock of reeds.

I joined them, pulling out my map and my taped up flashlight with the small hole in the center of its lens.

“Who was that?” I asked, unfolding the map and looking out to see what I could see of the hill in the dark, which was mostly nothing.

“Obrien, Second Platoon,” Stevens said.

I recorded the name into my memory for no good reason.

“The handset,” I ordered softly, holding my right hand out behind me.

The handset magically entered my open hand.

“Fire mission, over,” I said, knowing Fusner would already have changed the frequency to the artillery net.

I put one round of white phosphorus above what I thought was midway up the near side of the hill. I used a super quick fuse since I didn’t care if anybody on the ground was injured or killed. Seconds later the shell exploded, briefly showering part of the hill with flaming particles of the horrible burning substance. For some reason wooden bullets, like the Japanese had used on some of the islands of the WWII campaign, were banned by the Geneva Convention, but not the use of much more horrible napalm and white phosphorus.

The flash of light was enough to let me see the whole hill but gone so quickly I couldn’t adjust any fire using it. I called in for a battery of three using illumination rounds.

“Your position is on the gulf tango line,” came back over the radio instead of ‘shot, over.’ “Calculating casing and base impacts now. Are you in contact?”

“Negative on contact,” I sent back.

“What did they mean, sir?” Fusner asked, when I handed the handset back.

I wasn’t intending to fire high explosives until incoming fire began. I wanted to have the layout and plenty of potential targets of opportunity, however, when that happened. I had not thought about the company’s position on the gun target line. That meant that the guns were directly to our rear and had to fire over our heads to reach Hill 110. Since we weren’t at the extended maximum range of the howitzers, that wasn’t much of a problem for regular rounds, but illumination ammo came apart in mid-air a good distance from the target. Where the canister and baseplate holding the parachuted flares landed was sometimes life or death information.

I explained the delay as briefly as I could to the team. The fire direction center was busily calculating where each piece of every round was going to fall. They would not fire if any of those pieces were likely to impact on our position, unless we were in contact and absolutely had to have the light.

Minutes later, Fusner answered the shot and splash warnings. The rounds came screaming in, distinctive pops coming down from on high when the shells opened to permit the flares to complete their travel and rain down on the target. The whup, whup whup of the canisters sailing on through the air could be heard after the illumination rounds lit up the scene like an old black and white television screen.

I studied the hill intently, making notations on my map, but I didn’t have long to work. The illume rounds were still up there doing their thing when the heavy machine gun opened up. Green tracers began stitching back and forth along the perimeter line. The company had set in earlier, leaving one rounding curve of reed covered hillocks to be the natural perimeter between the company and the hill.

I burrowed into the mud. The giant fast-moving beer cans of green light fired by the gun blasted by. Terror swept through me, only relieved by the fact that I knew I had a twenty-foot thick berm of mud between the gun and me. That relief was short-lived, as a couple of lower rounds exited the berm right next to where I lay cowering. The fifty caliber bullets could go right through twenty feet of mud. That just couldn’t be, I thought, my memory of the weapons underrated capability in combat slowly returning. The .50 armor-piercing rounds would go through up to five inches of steel. Twenty feet of mud was no problem.

The machine gun stopped firing. I peeked out but the illumination rounds had burned out so I couldn’t see anything to adjust fire on. I shrunk back down, slowly realizing my mistake. I had illuminated the entire area between the hill and our own position. The gunners on the hill had taken advantage of the light to register their machine gun so it could accurately deliver fire all along our perimeter without the need to see the target. My own Army training methodology had been used to good effect. On me. “You’re not in Fort Sill anymore, Dorothy,” I intoned under my breath to myself.

“Why are their tracers green?” I asked Fusner in a whisper, just to make human contact. My hands were shaking badly again, but they only did it if they had nothing to do. I folded my map and then opened it again, and again, and again.

“Ours are all red,” he answered, also whispering.

I waited but after a few seconds knew that that was all the answer I was going to get. It was a physics problem and Fusner was seventeen. Physics was still ahead of him if he went on in school. I also knew that the color had something to do with the composition of the material used in the tip of the round. Magnesium burned red in a lab using a Bunsen Burner. I couldn’t remember what burned green. Copper. But copper wasn’t a material that would ignite on its own and trace across the sky. I knew I was thinking about the composition of tracers because I was so afraid. ‘Displacement activity’ it was called in anthropology. Anything to avoid facing the threat directly.

I forced myself to rise a few inches and look over the edge of the berm again.

“Assholes,” I breathed. “Fire your chicken shit little machine gun. I have artillery. Big boom.”

I somehow felt better and my hands stopped shaking in saying the words, even under my breath. I also wanted the binoculars badly. It was hard to feel like a real forward observer without them. They also would help penetrate the darkness. Not like the magic of the Starlight scope, but some.

I saw the machine gun open up again only because my head was up high enough over the berm. I ducked down, but I had an idea where the things were up on the hill, at least approximately. My mind had also recorded a second series of flaming bullets coming by me, from not thirty yards forward of our position.

M-33 Grenade

I hunched back down. I wanted to say something to Fusner but couldn’t get anything out. Artillery. I couldn’t call artillery. The battery wouldn’t fire this close and they knew where we were now. Thoughts bounced around in my head as the perimeter Marines opened up with their own machine guns and M16s. Somebody else had seen them coming. Grenade. I had two M33 grenades. I pulled one out, held the perfectly round little spewer of death and pulled the pin. And I lay there frozen. The spoon of the grenade was depressed with the death grip of my right hand wrapped tightly around it. In that position I’d become frozen, unable to get the grenade out with my body lying face down, the M33 and my fist crushed between my chest and the mud under me.

I breathed deeply in and out, trying to get control of myself. My ears rang from the nearby gunfire. After a while the shooting stopped and a silence fell over the whole battlefield.

“Fusner,” I finally grunted out, the side of my face in the mud.

“Sir?” Fusner said back, leaning down close to be able to make out my words.

“I’ve got a grenade under me and I pulled the pin,” I got out, my voice hoarse from fear and pressure. I still imagined the enemy racing up and over the small berm to bayonet me from above.

I felt someone else move up to my right side.

“Forget the pin,” Stevens said. “Just roll over and throw the grenade as far as you can out there. We’ll back up.” I heard Stevens slither away.

I had control of my breathing. Could I simply roll to my left side and toss the grenade over the berm without killing myself or any other Marines? And what must my team think of the stupid predicament I’d put myself in?

I rolled and threw the baseball size grenade, all in one motion, like I’d been taught in explosives ordinance disposal training back in Quantico. The spoon audibly clicked as it flipped itself away from the round body of the grenade. It was gone. Five seconds later there was a sharp crack as it exploded.

I edged my way back up on the side of the berm and turned, sensing movement.

“Fire mission?” Fusner said, pressing the radio handset into my hand.

It took only a moment to call in the topmost registration numbers back to the battery. I called for a zone fire mission after the single adjusting round landed just where I’d calculated. The battery then dropped six rounds on the point I’d chosen and six more on four other points forming the end of an imaginary X calculated by the FDC.

We set in to wait. If and when the fifty caliber opened up again, I would call for either a repeat of the same barrage or move the initiation point around until it was close to where a new position for the gun had been found. Ammunition, like for the 81s on loan from Lima Company, was limited in the field but there was no end to the amount of artillery that could be called throughout the night. The only real limiter was demand from other units in contact, if there were any.

Things remained quiet for some time. Nobody moved about at all but nobody fell asleep either. I patiently marked where the Hill 110 rounds had impacted on my map. When I was done with that I started counting. One one thousand, two one thousand, and so on. If I could count the long night away — If I could just live until morning — I might have another day. I figured I would probably be on a hundred and forty thousand or so, before first light.

“We’ve got company coming,” Zippo said, his nearby voice low and his words slow.

I moved backwards and down from the berm, and then crawled across the mud flat to join him. Fusner trailed behind while Stevens and Nguyen were already next to Zippo when we arrived.

“What have we got?” I whispered.

“Some of my old friends from the Fourth,” Zippo said, moving aside from the Starlight scope so I could stare through the green lens.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

You never forget the smell of the jungle mixed with burning gunpowder . There are still nights when I wake up and for a brief instant can smell it . Then realizing where I am I take a deep breath and wipe away the sweat and try to go back to sleep . Two tours without a scratch thanks to the lord and a lot of great men I served along side of .

That smell will never go away. I almost went back to Vietnam once just to walk the island again but thought better of it.

I could not figure out what I could gain and although I appreciate the Vietnamese and my old scout sergeant I still don’t want to

let it all go. Like some of the WWII guys and the Japanese I think.

Semper fi,

Jim

James,I am reading right along. I particularly enjoy your attention to detail. Perfect description of peering though a Starlight scope and hoping for first light. I carried one on a Army Lurp team in Vietnam. I was almost equally anxious about losing the thing as I was using the thing. Just another of the endless absurdities when you are twenty years old, in the thick of it.

Thank you Mark for the reading and the commentary. That damned invention saved my life a couple of times but what a bulky

reactive and undependable thing it was compared to the latest NVGs they use today. Semper fi, Jim

When was NGF on GoNoi? I called New Jersey on GoNoi fall of 69. Was Scout Sniper with 5th at An Hoa

68 Steve. We were way out there near the gun’s maximum range, as you know. At that range the damned rounds could not be trusted.

Impressive as hell when those freight trains went off though. Wow.

Semper fi,

Jim

My brother Spec 4 Paul E. Vaughn was wounded on Firebase Birmingham, on August 10,1971.

Sorry to read that Wayne. So many of us got our butts shot off over there and then returned home to a patched up society that wasn’t really ready for us at all. Hope he did okay.

Semper fi,

Jim

The terror of the night never ceased to leave me amazed that I made it to see the light of day again. I anxiously await each new chapter! You have stirred so many memories both good and bad but it’s good to bring them out. Semper Fi

Thank you Jack. It is the guys like you that drive me on into writing every speck of the experience…for those who cannot’write it or say it or sometimes even think it. Thank you most sincerely for the vote of confidence, your readership and your support.

Semper fi,

Jim

Shipboard testing of the old Mark 1A Analog computer was done constantly. The dynamic “B” tests ensured that with an accurate target speed input the gun target line bearing over a time span did actually meet specifications. In NGFS operations the speed and course made good by the ship was used as the “target” speed and course of the target with own ship speed input set to zero. The initial target bearing and range were set in and the time motor was started. After a series of “Marks” were done to know that the generated target bearing and range were computing accurately, we were then ready to engage with the spotter’s call for fire. Of course our limited range from just offshore could not help you folks in the Au Shau Valley. Your artillery folks were your life.

Received Naval Gun Fire once. It was the New Jersey firing into the Gonoi Island

area. Astounding that the 16 inche monster shells could reach that far inland. At the end of

its range though so accuracy was an issue and we were really scared of dropping those 2200 pound

shells down on ourselves. One must never be on the GT line when calling NGF.

Thanks Navy! Always had great service, care and fun with the Navy when I got the chance.

Army was that way too, not the way I’d been led to believe in training. And it was the enlisted Navy that was so

cool.

Semper fi,

Jim

Tough ass place! Army/Marines,all good men.Took three rounds myself different time and place. Waiting for next chapter.

Thanks Ron, it was something else again, as I am relating.

One former SSgt said he would have loved to be with me just

for the gallows humor later on!

Semper fi,

Jim

I can’t wait for the next chapter. As I read I can feel the darkness, see the willy Pete and the slime of the mud. Ready for more. The

Thank you Doug. I just finished the Fifth Night Second Part and am working on the third part of that night.

It was a tough night, but then I don’t recall having many easy ones out there in that mud infested mess….

Semper fi,

Jim

I thought VC and NVA used Dushka MG which were a little heavier round. I feel privileged to read your account of service.

You are correct Carl. The 12.7mm they used was similar to the Browning Fifty but had a heavier round flying at just a little slower speed for

regular ball ammo. Having run across a few in the field back then I never saw any armor piercing rounds and also discovered that their tracers were’green because they burned barium instead of magnesium. Thanks for the detail. I call their weapon a .50 for convenience and understanding and also because I didn’t know about the details until later on.

Semper fi,

Jim

I just keep wanting to read the next Chapter….

Thank you most sincerely Richard. It means a lot to have people interested in the time some of the bitter reality of real combat, at least

as it was fought in that jungle environment. Semper fi, Jim

Good read James takes me back keep em coming Semper Fi

Thank you Ronnie. Keeps me going, you and the other guys saying supportive things. Most of us vets who saw action have little or no contact with others that did and that can be a bit lonely on those dark days and nights when it all comes back.

Semper fi,

Jim