The door opened. It was a steel door about six inches thick, or so it seemed. It hit with a jarring thud when its heavy flat surface pivoted down and smacked upon the mud. Sunlight shot in like a wave of heat, followed by a wave of real heat, the air-conditioned inside of the armored personnel carrier likely to be my last until my tour was over. I had no weapon, no pack or jungle boots. I was new.

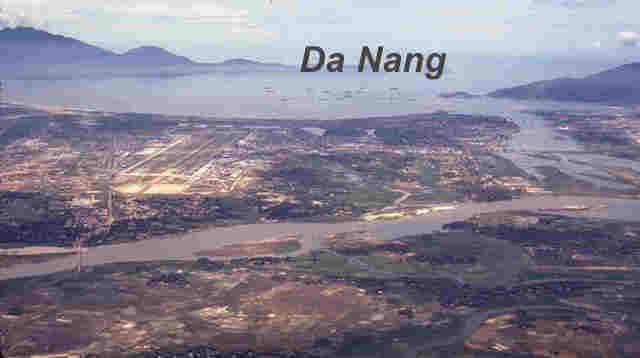

The civilian airliner had landed at Da Nang, offloaded a hundred uniformed men like me and then left without the crew ever getting off. No passengers had been waiting to come aboard. An F-4 Phantom fighter lay burning at the end of the runway. We’d all seen it before we touched down. The flight attendants said it was probably an old plane used to train fire fighting teams.

I hunched over, moving toward the torrid heat and light streaming in through the hole made by the back of the armored personnel carrier falling into the mud. We’d ridden maybe five minutes from the airport. Nobody told us where we were going or what we were doing, so I simply followed the silent procession of men out into the mud, dragging my government flight bag at my side. I was an officer but I’d taken the single gold bars from my utility jacket after being told by the plane crew that the shiny bars weren’t worn in combat areas.

Six of us had climbed into the waiting carrier. There had been other carriers but I had no idea where they’d gone because when I stepped outside, only one remained. A tall Marine staff sergeant stood facing the rear of the vehicle about fifteen feet away, on more solid ground. His boots gleamed in the sun, his spit shine on each, perfect. The pleats on his uniform, a short sleeve Class A in khaki, were ironed so starchy sharp they looked dangerous. Unaccountably, he wore a D.I. instructor’s flat brimmed hat with a small black leather tassel dangling from its stiff edge. His hands were on his hips, his elbows sticking out looking as sharp as the pleats running up and down the front of his shirt.

“Gentlemen, welcome to the Nam,” was all he said, waiting a few seconds for his words to sink in before turning and heading off on a path through the thick undergrowth.

It was the first day of my time in Vietnam. I was unafraid, my emotions blocked by wonder. The light, the heat, the thick cloying mud with a burning Phantom sending up tendrils of black smoke snaking across the sky, masked everything else I might be feeling. The plane I’d arrived on was from America and it was gone, America gone with it. I moved along the rough hewn path, my flight bag knocking into the ends of every hacked off branch. I was nobody. I didn’t feel like a Marine officer or even much of a citizen, and I sure wasn’t in California anymore. I was a slug moving through a forest that looked like something out of a bad horror film, following an enlisted man I was supposed to out rank but who apparently didn’t think so, toward a destination nobody had told me about. I was not disconcerted. It went deeper than that. In only moments, with no warning, I’d become lost in another world that defied the darkest imagination. We came out of the bush to see a wooden structure in the distance.

“Gentlemen, the Da Nang Hilton,” the staff sergeant announced, continuing to lead us without pausing or turning.

Just before we came up to the building, he stopped. We stopped behind him in a row, as if we were in a squad he commanded.

“It’s got a moat,” one of the other men said, pointing at the five-foot-wide stretch of water dug between us and the building. A thick plank extended out over the water to allow access to a ratty five story wooden structure beyond it.

“That’s a benjo ditch, not a moat,” the staff sergeant indicated. “No bathrooms here, except for the ditch.” He stopped and ushered us up, one by one, onto the plank. “They’ll come for you when they come for you,” he said to our backs, walking away after the last of us crossed.

There was nothing ‘Marine Corps’ about the shanty of an open barracks . No windows or even walls. Wooden pillars held the wooden floors up with a big tin roof covering the whole affair. I saw so many bunks it was impossible to count them from the outside. A corporal sat at an old metal and rubber desk taken from some earlier war supply house. I watched him deal with the officer in front of me, making no attempt to hide his boredom. “File,” the corporal said when he finished, holding out his hand toward me. “That’s your bunk. Break the rack down and make it with clean stuff in the cabinet down at the end. No lockers. Keep your own stuff close.”

There had been no “sir” in any of his delivery to the guy in front of me. There was none to me either.

“Tag,” he continued, handing me a metal edged paper tag with the number 26 written on it’s white surface. First floor. Officer country. You heard the rest.”

I wondered why officers were quartered on the first floor. I presumed, as I made my way to rack number 26, that it was because the benjo ditch aroma would be more available. The rack was filthy when I found it. The place was nearly full with men recently returned from combat patrols or whatever, I presumed. Most were covered with mud. None looked like they’d showered or washed in days or maybe even weeks. I hauled the old sheets to a bin near the end of the narrow row that led to my bunk. I tried to talk to a few of the other officers who lay without sleeping atop their muddy beds. They would only look back at me like I was some specimen on display at a zoo. They would not answer. Not one of them. I finished making my bed, deposited my flight bag under my cot and then huddled with my back against a corner support. The bunks were four high with a slatted ladder going up on one end. The three bunks higher up my tier all sagged with the weight of other officers in them. Their packs simply lay all over in the aisles with junk loosely attached to them. Junk like muddy guns and grenades.

It started to rain. Like the day was not proving bad enough with the smell, the mud, the zombie company and a miserable cot without a mattress as my supposed resting place. There was no pillow either, but there were mosquitoes. Perfect. It was at that moment that I became afraid. I’d never been afraid of anything in Marine training, other than the very likely fact that I might not get through to become a Marine Officer. That I was second in my OCS platoon, and then won The Basic School Military Skills award, only reinforced the fact that I’d found my calling. And here I was, in absolute squalor, trapped in misery with a bunch of other men who’d preceded me and who now appeared all mentally ill. What had happened and where was I really? I’d seen all the war movies through the years and I’d never seen anything like where I was. Nothing close. Those wars and those characters had meaning, relationships, communication and decent clothing. I had shit. Quite literally.

I tried to lay down but could only cower and slap at the mosquitoes. From a bunk above, someone tossed a small clear plastic bottle. It landed on the wooden floor with a small thunk.

“Repellent. Use it and then shut the fuck up,” a voice said from above. I leaned over and picked up the container, the voice presumably registering a complaint about my slapping of insects. I rubbed the foul but strangely attractive oil onto all the exposed surfaces of my body and returned to my previous position.

I passed the time, as the sun set out in the rain, watching mosquitoes land but not bite me, as if they sensed a tender morsel nearby but couldn’t access it. The repellent didn’t repel them at all. It simply made me less edible, which was fine by me. Only a few of the other men had flashlights or bothered to turn them on. I had nothing in my bag except some extra socks, underwear and a useless change of street clothing. And my hard fought proudly worn gold bars.

I waited. Even though it was still early, I knew there would be no sleep. I recorded each passing moment by reading the luminous dial on my special combat officer’s watch I’d bought at the PX stateside for fifteen bucks. At eight o’clock a face appeared before me — a man holding a flashlight so I could see his features.

“Welcome to Vietnam,” the face said, its eyes not looking at me. “Chief of Staff will see you now.”

Another zombie, I concluded, already getting tired of hearing the welcome phrase.

“What’s your rank?” I asked.

“Buck sergeant,” the illuminated face replied, staring out into space, waiting.

‘Then call me sir,” I replied, getting out of the bunk to follow the him.

“If you like,” the sergeant said, not saying another word — certainly not sir.

My first day in the welcoming Nam was over, and my first night about to begin.

30 Days Home | Next Chapter >>

LT, what a great reminder of how your adventure begin.

Thank you for posting.

Thanks a lot JT, glad you took the time and trouble to look back.

Semper fi,

Jim

jim ; when I was at oak knoll homer an jefrow came by our ward you got rachal you lucky stiff I was the only one that even new who thoses hillbillys were. I’m with judie at st lukes kc mo. this is tougther then nam seeing my wife like this. shes losing her mind with all the drugs. her new kidney isn’t kicking in yet an shes back on dialisas. my oldest son is flying back in tonight from virgina. dr think they can get her head to clear up. hope the book I send is of some value.i gave the itune to my granddaughter.i don’t know how to use them.hope to visit later your friend omer.

Finally got to this comment Omer. Glad Judie’s kidney is kicking in since you wrote this…

Semper fi,

Jim

I prayed and it worked so I feel good!

Hello James Strauss. I would like to introduce myself to you and tell you why I want to you about me and hoping you can help if you’re could. My name is Tri Doan and I was born on June 1st,1972 in Vietnam. I had been looking for my Dad on Ancestry online for last 2 years. On and off checking online information about him. About 4 month ago I have told my Mom that I was looking for my Dad online and I would like to ask her more information about my Dad. She said she did not remember anything about him except the sound of his name or last name is “ Strauss”. To make story short today I went online and type in Strauss and your story pop up. I read the first chapter. I am interesting to get to know you and I would like to ask you more information during the time you’re in Vietnam. if it’s possible you could email at dnatri72@yahoo.com. I am looking forward to hear from you soon. Have a wonderful weekend. Thanks

I can appreciate your journey seeking identity, Tri.

I was in Vietnam for 30 Days, each day in the “jungle” of the A Shau Valley.

I hope you enjoy reading the story and someday find your ancestor.

Thank you very for let me know it. I am really much enjoy reading your 30 days in Việt Nam!

Thanks Tri for commenting about your enjoyment on here. Keeps me motivated and going….

Semper fi

Jim

Flew in to Pleiku. I’ll never forget walking to the door on that plane and in an instant went from AC cool to being smashed with hot, humid air. It was overcast and lightly raining as we rode a bus to the repo barracks. Unloaded on to a field of ankle deep mud and in out starched khakis and low quarters struggled down the hill to the new barracks still smelling of wet freshly cut wood. A SSG welcomed us, gave us booklets on Vietnam and lectured us on being guests in their country. Shortly after I got grabbed for shit burning detail. By then the sun was out and it got even hotter and more humid. Like others have said, the smell of burning kerosene and shit will never be forgotten. Later in the afternoon I got orders and put on a Caribou headed for Qui Nhon. We did a deep dive landing at An Khe onto some of that steel matting to drop off some troops. That combination had me worried about what was ahead. As it turned out I got lucky and ended up as a REMF for the year

Thanks for starting the read Marty. And thanks for writing about it in detail on here.

Your own story sounds damned interesting, as well. Glad you made it to the rear, where we

all wanted to get to but generally didn’t.

Semper fi,

Jim

Well done James Strauss great book, well written, thanks for sharing. I was there 1970-71

Thanks for saying something here about that and being one of us Walter!

Semper fi,

Jim

Were you around LZ Profesional 68/69? I was on that hill, wasn’t fun.

Professional was over in Dragon Canyon, another hotbed of trouble.

I was parallel in the A Shau, further west.

We could not draw fire from your artillery there because of the range.

Thanks for the comment,

Jim

I have enjoyed the first twelve days immensely. However I have been unable to advance to Day 13. Any particular reason?

As of early this morning it isn’t finished yet. ~~smile.

I am posting as I write.

Thanks for your support, John

Semper fi

Jim

James, I just stumbled onto this site from somewhere else (probably a link in a Doug Rawlings article…). Thanks for setting up this site to tell your story. It is with a certain amount of dread that I look forward to reading the rest of it.

I was a one hitch REMF. U Tapao, Thailand, 1973-74, working on BUFFs and KC135s. For the longest time after discharge I felt I was neither fish nor foul. I was classified a Viet Nam Vet because I was in the theater of operations, but having never put boots on the ground in-country I didn’t feel I had earned the right to that label. That if I did it diminished the significance of those of you who did.

At some point in time, I resolved to say I’m a Viet Nam Era Vet and specify I was in Thailand, not Nam, when anybody asks. (Not that that many do ask.) I’ve found an uneasy peace with that, for now.

I’m glad you made it back. And thank you again for telling us your story.

Go easy into that peace. We sure as hell needed all the support you gave, no matter

how ancillary it seemed to you. You were part of the body of that metaphorical pen and the vital ink inside it.

That we were the tip laying down the words was just a different job of the whole. Thanks for your work

and please be a Vietnam Vet the next time. We need all the guys we can get and besides, as the other guys here will attest,

you are one of us…

Semper fi,

Jim

I landed in DaNang late May 1965, to join MCB 3, it was quite a shock for a 17 year old, I did my two tours before my 20th birthday, as a heavy equipment operator in the SeaBees, I was not faced with the things that the Marines and Army had to face, but the threat was always there. Glad you guys made it back.

That must have been one hell of an interesting time to be there,

because you went home and all the war after and stories about it followed.

You saw it all before a lot of that happened and must know quite a bit because of

how much ground the equipment operators had to cover. Be fun to talk to you one day

about al of it.

Thanks for commenting here and reading the story.

Semper fi,

Jim

Enjoy your writing and have gone back to read from the beginning and in sequence. I had a different arrival. I went over early Feb ’68 with BLT 2/27. I was a radio operator with 2/13. We only had roughly 72 hours notice. Came in from weekend liberty at Camp Pendleton (camp Las Pulgas) on Sunday evening. Was informed we would be in Danang as a BLT by Wednesday or Thursday.

We flew from El Toro on C-141’s. It was organized chaos. I was told to get on a specific C-141 with 4 other marines, a 105 howitzer, a MRC-110 com jeep, and a pallet of ammunition. We refueled Clark AFB then into DaNang. Being very young marines we thought we would have to fight our way off the plane. Once landed the back end of the plane opened to reveal the largest airport in the world – then. Being a radio operator I spent time in field with FO’s – usually a E-4 or E-5 and in FDC talking to marines in the field. Very interesting experience. Great satisfaction putting arty right where it was needed.

Fight your way off a loaded C-141 Starlifter. Hilarious. I am picturing

you guys when the plane hit the runaway and you are all crouched down.

funny as hell. Like the movie Stripes. Glad you liked delivering the arty

we need so badly out there. The Marines, Army and Air won that damned thing

before the politicians stepped in and decided that we hadn’t at all.

So here we are.

Thanks for all the detail of your comment.

Semper fi,

Jim

Semper Fi Jim. Riveting read. Curious, when did you arrive in country and what Regiment were you in ? I came to RVN January, 1969. I was with G.2/9. A Shau Operation Dewey Canyon. Is your story in that time frame or after that Op.

Thanks for your service, welcome home

John DiDomenico (Doc D.)

Hey, MCB 3 – I went in the first time in early April 1965 with 3d Marines. I think it was you guys who moved in just below us, between our regimental headquarters and Dog Patch. You guys came in and made showers and a club appear like magic, and invited us to share them. You can’t imagine how much we appreciated you.

James, you’re right that early 1965 in the DaNang area was really bizarre. We actually got liberty in DaNang and saw some of what it must have been like before WW II and for a while after that. The bar in the DaNang hotel looked like a set for the Alan Ladd movie “Saigon”, and was pouring Martel’s VS for bar brandy. There were excellent restaurants; great bread from carts on the street; really good tailors, if you can believe it; and everything even cheaper than Japan and Oki had been.

The second time was Hue and then Quang Tri, Aug67-Apr68 – not so much fun.

Thank you for writing about this stuff.

God, but you make me wish I’d gotten around a bit in the Nam

before I hit the field or had time along the way.

Interesting, near movie, quality images you float before us…

Semper fi,

Jim

First of all Thank you for your Service and “Welcome Home”. Something we never received upon arrival back to the “World”. I was sent to the Army replacement station in Long Bihn, while awaiting orders and that was by far, the nastiest place I have ever experienced. I presumed it was a prelude for things to come and I was not disappointed. My duty station was in Can Tho down in the Delta region and upon arrival with two other Spec. 4’s we stepped off the C-123 transport only to see 3 body bags to be transported back to Saigon. That was the most sobering moment I had ever witnessed to that point but that was on day 3.

Jet Fuel, burning S**t and to food smells still linger.

Your entry was a lot like my own Doug. A Pre-cursor of things to come, and none of them good.

Thanks for the detail and sharing the similarity. One of the problems I will face in telling and

getting this story out is credibility. Even though I have the track record and decorations, the system

is not going to be pleased.

Thanks for the support.

Semper fi,

Jim

We arrived in Cam Rahn during a hot Feb. night in 69 aboard a TWA freedom bird. The Captain welcomed us to Vietnam like we all wanted to visit there. Boarded an Air Force bus and went to a welcome center where they threw us sheets and told us to find an empty rack to get some sleep. An hour later we were laying there in scared silence when we heard the sirens as rockets were walking across the billet area. By the time it was over 3 of the guys who came in on the plane were dead and heading home. Welcome to Vietnam, I wasn’t in Idaho anymore.

Some people back here don’t get what it’s like to hear the word “incoming” and know that there may be no place to go.

Hell, when your brand new you don’t think to figure out where a close bunker might be!

Then the word comes and everyone runs like a chicken and you can’t figure out that you might want to follow one of those wild chickens.

And there you are….

on the next plane out, either dead or wondering what that was all about…

Semper fi,

And thanks!

Jim

Jim, My first night was very much like yours. Our huts were very close to one another. When the mortar rounds (incoming) came in I just followed the crowd. Later learned It wasn’t my assigned bunker. My guess was that it was the VC way of ‘greeting new replacements’. Bien Hoa 67-68 (tet offensive)

My brother was hit at Bien Hoa with the Big Red One. He made it to

the hospital and then flew home but his plane crashed. Anyway, yes,

it is interesting just how many of us were plopped into the FNG position

no matter what our rank.

Thanks for the comment and the support.

Semper fi,

Jim

I think this is the definitive book on Vietnam and the USMC’s part in it. Well done James. It’s a difficult read but I could not put it down. This may be superior to Karl Marlantes’ “Matterhorn”.

That is high praise indeed. Matterhorn is the very top of the peak of Vietnam war books, not matter what the

service or time…

Semper fi,

Jim

I arrived in cam rahn replacment center on june 5 70 . The middke age

stewardes made a comment about welcome to vietnam and we hope to see most of you on your return flight.

The next day I got on a C130 with 4 other fngs to go to bien wa . Then they started loading cages of chickens , and strapped of unwilling hogs to the deck then loaded the rest of the space with Vietnamese families.

Then we sat and waited for clearance to takeoff , I had bever been airsick befire but the heat , and stench from the people the hogs shiting and the noise of the vietnamese kids screaming crying was getting to me

fortunately we tookoff soon and the cool air as we reached altitude cured the urge to puke. Enjoy your memoirs , write on welcome home

Geez, Lucky, that comment was something to read indeed. Like it was.

I so identify and yet have never talked about the real details back here.

Who can tell someone that the first thing that happened is that you got sick?

We were supposed to be warriors. What the hell! You make me feel better

about life and what happened. it’s so easy to think you are alone out here.

Semper fi,

Jim

I was an Army 2LT. My first arrival wasn’t bad like yours. I and a hundred other guys stepped off a civilian airliner in an orderly manner in Pleiku. It was early morning. The vista was a huge flat airfield with green mountains in the distance. A threadbare, stained, aged-looking column of soldiers were to one side, waiting. I realized they were waiting to get on the plane and go home. They didn’t mock us. Everybody in charge of us was kind but impersonal. They all said “Welcome to Viet Nam.” I didn’t see any bomb craters, wrecks or ruined buildings. There were some satifyingly warlike-looking pillars of smoke around the horizon in the early sunlight. I knew enough to keep my mouth shut, but in my mind were two questions: Where’s the war? And: What’s that smell?

Real shit Rick Gauger. There were so many wars fought within the war over there. Just a few miles away could mean all the different in the world, or if you got to stay in the rear areas. So bizarre in its accidental (and sometimes not) combat exposure. The smells were wild and remain with me today. I drove through a neighborhood in Santa Ana, CA years ago. It was newly populated by Vietnamese. The smell of the fish sauce wafted in and I had to pull over to get myself together.

Thanks so much for your comments. Means a lot to me. Hard to keep going because it was all so unlike my medals or the citations accompanying them. It wasn’t heroic and it was many times shameful. I did not conduct myself intelligently or well. I live with a lot of regret that I’ve been able to handle but is still all there.

I could have done so much better than I did.

Semper fi, Jim

I was in the Intel branch, 1st Cav Div. I spent my tour interrogating with my little team at many brigade level LZs. About once a month I would make my solo way with an ARVN interpreter and a POW, begging for helicopter rides to little platoon-size LZs here and there in the mountains and hamlets, where I would persuade some LT or SGT to escort me to some map coordinate so I could retrieve a cache or some dropped equipment. The infantrymen were astonished at me, my ARVN, and my VC prisoner. We would hike over some mountains and they would stand around smoking cigarettes while I turned over dead VC to photograph their faces. In pursuit of this, a couple of times, I did my own tunnel-crawling, super-slow, checking for booby traps. Today I am amazed at how well I was tolerated in these places. My mouth only got me into trouble once. I was at the language school but never was fluent. With the help of my interpreters (they were my only constant companions) and hundreds of POWs I learned more about how the enemy did things than I did about my own army. Sometimes we would find something interesting, usually not. Sometimes I thought we saved American and Vietnamese lives, sometimes I thought we only thought we saved some lives. I failed to overtake some US POWs who were being taken north. It was probably just as well because I had no idea how to get them back alive. I was usually kind to my prisoners, sometimes not. I saw, heard, and participated in, some things that were so stupid and shameful that today I have to forcefully shut down my brain when these things come to mind. I was and am a college graduate and an Army brat. I spoke Spanish and German and some Vietnamese. I lived all over the planet when I was growing up in the 50s. I knew that the only reason we were in that war was because of America’s history of dumb anti-communism and because of our fumbling after WWII. I was there because I was doing what I thought I was supposed to do, for my father, my teachers, and my country. We all felt that way in those days. I did all this stuff without ever stumbling into an enemy patrol, without ever being the first to step on a booby trap, without ever being hit by any of the snipers who took a shot at me, without ever crashing during one of the dozens of plane and helicopter rides. I came out of all of it, and a second tour, without a scratch. In 2000, after thirty years of unemployment, I was awarded 100% for PTSD. I survived and I’m OK (really) — I published an entertaining sci-fi novel — and I’m happy (really). But I can’t hold my head up much when there are real disabled vets around. After all that, America still invades Iraq in 2003, disregarding the advice of every expert in the intel community and the State Department. Someday God is going to get tired of the USA and our luck will run out. Maybe He did already, and he sent us Donald Trump. You can edit out those last three sentences if you want to.

Can’t edit out that kind of opinion Rick, not when it’s so well stated and founded

in history and current reality. You are a man among men and your recovery from what you

went through is terrific. Thank you so very much for taking the time and trouble to comment

and tell your story here. There were so many micro wars fought over there and it was like back

here is one way….where you end up being has so much to do with that being….

Semper fi,

Jim

I had to drop from an E-4 in the USNR to an E-2 to join the Army, with dreams of high school to OCS. Never made it to OCS. Asked for Military Police and jump school. Finished basic with orders to Aircraft Mechanic school at Ft. Rucker; Trained on the Bird Dog and Beaver. By the time I finished the first second phase I was a Sp-4 with over 4 years prior service. Failed the run for the Airborne PT Test. Wound up going to Germany. Volunteered for the 7th. Army NCO Academy and graduated. Went before a promotion board on a Friday morning and was to report after lunch with buck Sgt stripes. This a-%ll happened way too fast. I was sent to the field on a training exercise in charge of the Aviation section and the SSG stayed home. I was clueless! I had never been to the field except for Bivouac at the end of Basic. My best friend, a new Sp-5 turned on me like a wolf. Hey Sarge, where do you want the tent, etc. I re-up’ed for 6 and got orders to Rotary Wing Tech inspector school at Ft. Eustice enroute to Vietnam. I had never worked on a helicopter and was being trained to inspect the work of experienced mechanics on all the turbine engine helicopters. I arrived in Vietnam and a clerk saw my orders and said “Wow! Tech Inspector! You must know a lot about tools” and turned and ran upstairs before I could say No I don’t! I wound up in Phu Loi and never touched a helicopter. Within a day or so after my arrival in Phu Loi, I was sent to Long Bin for in processing. The truck driver dropped me off and told me to hitch a ride back with another unit. I did manage to get a ride back with some guys going to a place called Xeon. When they got to their turn off they dropped me off to continue my hitch hiking. I was a little nervous, being alone in Vietnam with no weapon as the sun was going down. Thankfully an RVN convoy came along and a Duce and a half stopped and I climbed on back to sit on boxes of rockets. I made it safely back to Phu Loi and had a relatively peaceful war. Thinking back it was one of the worst examples of leadership I’ve ever encountered. No horror stories. Just a heart full of gratitude. I’m glad you guys all made it home too. Welcome home brothers. I retired as a first Sgt. in Hawaii, after 23 years.

Gosh darn! Talk about a wild and twisting adventure all of your own!

There were a lot of disconnections going on over there. Sometimes the choppers would deliver

FNGs we had no paperwork or anything for. And our wounded were taken away never to be heard from

again. Nobody ever rejoined us from the rear. Ever.

Thanks for the lengthy story and the interesting odyssey.

Semper fi,

Jim

Memories. I landed in DaNang Jan. 69 around sundown. There was a light drizzle rain. After leaving the plane everyone dispersed like roaches looking for a hiding place when the lights come on. I was 19, several thousand miles from home and lost. It was dark and I had no idea on where to go. I found an empty building with some racks and mattresses. I manage to crawl under a mattress and finally went to sleep. I was so tired and don’t remember waking up during the night. The next morning everything looked different. I wasn’t in Ky anymore. This stuff was real. This was Vietnam in the daylight. Luckily I found the flight that was to carry me to Quang Tri and the red mud and dust of Vietnam.

Thank you very much for sharing your experience, “joe”

It was a strange place to be in so many ways

The door opened. It was a steel door about six inches thick, or so it seemed with the jarring thud it made when the its flat surface pivoted down upon the mud. So a plane with a 100 men landed in the Mud and then left without the crew getting off. I don’t believe you landed in the mud and then the plane left I worked on the flight Line those planes dont move in the mud.

Darrell, I am so sorry I was not more clear. The armored personnel carrier picked us up from the plane and then dumped us not far away through the jungle just distant from the Da Nang Hilton, or what they called the edifice. The steel door was the back door on the personnel carrier, although it may have been the front door, as I think about it. It was a long time ago. Many memories are so vibrant and others a bit dimmer….thanks for your comment and thanks for thanks for ‘being there.’ Jim

I landed at Ben Hoa on a Flying Tiger civilian airline.

We rode in back of a deuce and half to 90th replacement at Long Bihn. We walked by a infantry unit and I had never seen men so filthy in my life. We were afraid of them, they did not acknowledge us.

The heat was horrible. Several hundred of us got in formation. I remember some men passing out and busting their nose and face. I remembered don’t lock your knees. This Sargent came by and said, “you, you and you get on back of the truck, you are on the shit burning detail.”

We had never heard of shit burning but that’s what I did all afternoon.

Shit burning smells like shit burning.

That was my first day.

There was a lot of Shit Burning in Vietnam in so many ways……

Hard to imagine but hope your subsequent days went a little better

My arrival was similar but guys were boarding the plane I got off of returning to the world, several rockets came in and killed two men in the return boarding line. Suddenly it was really real!

Bill and Morris,

So many of our finest were mowed down quickly….

Really appreciate your support.

The day I flew out of Nam, on emergency leave because my father had died suddenly back in the states, we flew from Hue over Da Nang and looked down upon the 1968 Bob Hope Christmas Show in progress. I missed my Christmas in Vietnam, but made it to Green Bay just in time for my father’s funeral, still wearing my tropical tans. On reflection, my father may have saved me. Who knows…

Sorry to hear about the circumstance that allowed to leave the MESS, but appreciate the fact you made it out OK

When asked why I joined the Marine corps, I have two answers which actually translate to the same answer. The first was that if I was going to be in the military because of the war, I wanted to be in the front row at the Bob Hope Christmas Special, and the second was that if I was going to be in the service because of the war, I wanted to be in the war. On Christmas Day of 1969, I was about three miles from Freedom Hill (Hill 327) at Da Nang listening to the Bob Hope Christmas special on AFVN. I did however have a friend who made it to both the 1969 and 1970 specials, and met Bob Hope before the show in 1970. They had about a fifteen minute chat, and Bill gave him a copy of a scrap book he had put together which included many photos of our tour.

Many years went by, and Bill got a call asking if he was the creator of that scrap book. When he answered that he was, a representative of the Library of Congress explained that they were preparing an exhibit honoring Bob Hope’s service and they had that scrap book and wanted to include it in the exhibit which was to be a permanent exhibit in the library, if they could get his permission. Bill said not just yes, but heck yes. They invited Bill and a guest of his to the unveiling, and Bill and his son were seated at the table with Bob Hope and his Daughter for the dinner. If you ever see the display, Bill’s album is the one opened to a page with a picture of a lovely young Oriental lady in a bikini. That’s the same picture which was included in our 1969 cruise book.

Bill extended because he wanted basket leave to Australia and because he wanted to go back to the 1970 Bob Hope Christmas special to present that book to Mr. Hope. In true Bill form, he went to that special as well.

In 1969, I was setting on a revetment which surrounded a bomb dump south of Da Nang looking out across Dog Patch and listening as the first man stepped onto the moon. Five months later Neal Armstrong walked onto the stage on Christmas Day in Da Nang. If you watch the Bob Hope Show on the video “Salute To The Troops – Bob Hope The Vietnam Years”, they have the Neal Armstrong address to the crown on that day, and as he leaves the stage, you will see a long lanky Marine catapult himself across the crowd to be the last Marine to shake Neal Armstrong’s hand on his way off the stage.

That was Bill, and in January of this year he left us.

Semper Fidelis!

I heard about the Hope shows, and I never heard a bad thing. Raquel Welch visited me in the hospital

in Oakland and that was something, indeed.

I am so sorry about Bill. And the scrap book is in the Smithsonian.

That is so cool.

Thanks for telling us all on here and spending the time

and space to tell a whole lot more too.

Semper fi,

Jim

My dad was USAF stationed there in 69 – he went over as a chief master sergeant. Would his experience have been similar? He was in communications – sadly he passed away a 18 months after his return at only 39. It would have been bitter-sweet to be able to talk to him about at as an adult but I was only 15

Thanks for your comment, Diane.

Your father’s experience was most probably similar.

I am truly sorry to hear of your loss at such an early age.

Diane do you know what Squadron your Dad was in? I was there in 67/68 on Tan Son Nhut in the 1876th Comm Sq.

Typically your Dad’s experience would have been very different from that of the Army or Marine Corps. We normally slept in a decent bed in an open bay Barracks and we also normally had hot Chow 3 meals a day. I did spend a few nights in a hole dodging Mortar & Rocket Fire and also we were hit with ground attacks every once in a while. Other than coming away with Agent Orange exposure and one little scrape I came home without being injured.

We buried my wife’s 1st Cousin yesterday who had been drafted and served his time with an Infantry Unit in Nam. Even though I had seen him from time to time I really didn’t know much about his experiences. I only knew that it left him being chased by demons that he was never able to be rid of. RIP David!

Glad you had a better position on the field of combat.

It’s not like taking incoming is not combat either.

That is hard junk if the rounds come in close and the terror of the enemy coming

through the wire in the dark after the attack, even when they don’t, was tough as hell.

The chopper crews had some real seeming benefits too,

but hell, I can’t imagine having to then get up every day and go back out into the shit.

At least I was stuck out there.

Semper fi,

Jim

gritty…and reminiscent. my arrival in Bien Hoa was in a transport plane that caught enemy fire as we were landing, and sort of belly-flopped onto the tarmac, where we waited spread out face down for hours.

Is there any wonder that the public, as we have come to know it back here, has no comprehension of what so many of us went through. Right out of the box!

That smell of burning s**t was the main thing I recall definitely worse than the first day of school.

There were so many “different” smells for sure, Daniel

To this day it is the smells more than anything that bring me back.

I was driving one day, many years ago, through a neighborhood in Santa Ana, Ca with

a friend looking to buy an apartment building there. My friend and I had come home about

ten years earlier. We drove unwittingly through a neighborhood populated exclusively with

repatriated immigrants from Vietnam. Our windows were down. The smell of the fish sauce

suddenly permeated the car. I had to pull over. I could not drive on. I looked over at

my friend and he was crying silently. There was nothing to be said. We sat there, taking it’ all

in, back but not back, for about twenty minutes, until I could drive us out of there. We went to

a bar and that was it for that day and night. The sense of smell can be a tremendously powerful emotional reactor.

Thanks for the remembrance and the comment.

Semper fi,

Jim