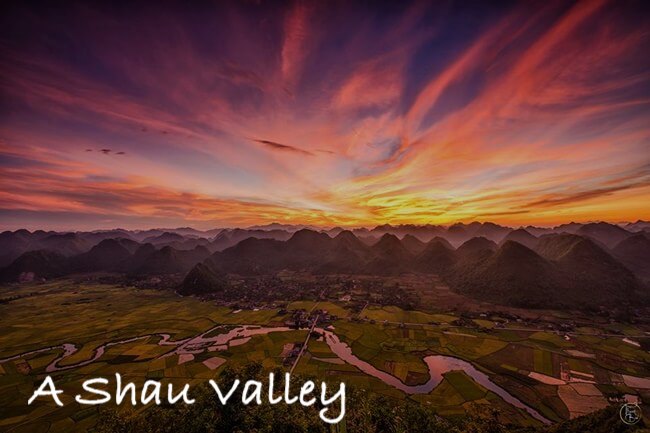

I lay in the muck of oozing mud seeping slowly up through the packed, cracked, and broken debris of jungle and aging decay. The smell was of the damaged sort I’d come to know as my home away from home down inside the A Shau Valley expanse. I wondered if the smell would ever leave me, should I somehow have the good fortune to survive my experience in actual combat. I’d come late to discover that I, inadvertently, had built the confidence of the Marines around to such an extent that they had gone from being ‘dead men walking’ to believers that they might make it through the Vietnam war experience and one day go home without serious disfigurement or injury. I had, however, not built up that belief system inside myself. No matter what I did in the few moments of rest or reverie that I had it was impossible for me to believe that I could survive another year under such conditions.

The dawn came creeping up and over the far eastern wall of the canyon rim, with the first tendrils of light visible only like a faint glow across the clouded sky that had to signal a return to monsoon rains. The respite through the night had been too long and too good. The enemy would be able to use the monsoon rain during the next night to cloak another of its relentless attacks, and very likely a fully coordinated and successful one. I peered upward, toward the top of the western lip of that canyon wall but could see nothing. It was time to move from our position, I knew, and a plan was beginning to form in the back of my mind for our next survival attempt.

Glad you recovering and getting well. took me a while to get into reading about combat again. now back in the groove or should I say groovy. still one waiting for me on to the read I go. Don

Thanks Don, means a lot right now and I’m not kidding.

Semper fi,

Jim

When will the third 10 days be available for purchase?

As soon as I complete the last segment, Mike.

Thanks for your patience. I am back in the strength mode.

As usual another exciting chapter. Waiting to see how the new Lt. works with Sugar Daddy’s people. Smoke and prayers for your quick recovery.

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

LT-

Glad you are back in the Saddle.

Latest chapter is great!

Bypass will buy more time plus you now have more blood flowing and more blood means more oxygen flowing.

The NAM adventure was a hard year.

We get it.

Keep writing 👍🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸

Thanks for the well wising and yes the blood is ‘flowing’ once more, along with the ink!

semper fi,

Jim

I appreciate your support, Chris

I am mending form the heart surgery but now this Pandemic has so many lives upside down, it is difficult to stay as focused as I want to.

Semper fi

Jim

Hoping the operation went well & you are on the road to recovery. Gentle hugs for you & your wife.

Jim’s daughter just let me know surgery was a success and Jim is in ICU most probably through to Friday.

He will probably be answering a lot of these wonderful messages over the weekend.

Chuck

Very first and most important, Lt. may your medical procedure have the best possible outcome.

Your writing is good and something I look forward to. I was not involved personally in the madness of that time but was close enough to know of it and as the decades have passed have tried to get my mind around all of it.

I’m noting in the first paragraph the sentence, “I lay in the muck of oozing mud seeping slowly up through the packed, cracked and broken debris of jungle detritus and aging decay. ” is trying to carry a little too much with use of the terms ‘detritus’ and ‘debris’. My opinion, of course.

very best going forward.

Jim Adams

Chuck Bartok here standing in for Jim. Today is day of surgery.

I removed the word detritus and it does sound better.

Jin appreciates your support

Thank you Sir! You are in my prayers. Semper Fi

Take care of yourself Jim. Your recounting of your story has taken this long and it can certainly take a little longer.

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

May your surgeon/s be the best. Heal as fast as life allows it, we will be waiting. ben

Thanks Ben, I am in at oh five thirty tomorrow and wish the Gunny was here watching over me.

Semper fi,

Jim

I keep thinking – that damn bridge – and I’m surprised the NVA hasn’t made a major effort to destroy it somehow.

Personal note, I also had a brother in the Army at Bien Hoa, he’s no longer with us.

SEMPER FI

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

Thanks for bringing back an old song from Jr. High. Could not remember the band. You and your men bring tears sometimes to this old soldier’s eyes. You are one of the few writers that speak of the dysfunction in the military in those years and hidden blue on blue violence that seemed to permeate my memories from 70 to 78. It was a hard time to serve for many of us. Thank you for serving and being courageous enough to tell your story.

Many of us our age are finding our bodies are no longer 18 or even 50. Hope for a speedy recovery. I am not far behind you on the heart issue LT.

You are simply this wonderful class act SSG

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

LT My prayers are with you and your family as you go through this medical speed bump I will post my thoughts on this chapter after I know you are in recovery God Bless Salute George

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

Another great chapter.

Good luck on your procedure today. Please keep us posted.

Hey L.T. Hope the recovery from that surgery continues to progress nicely. I enjoyed this last segment and have quit trying to predict the chain of events. Which just proves that life is not a novel. The story I read here seems an unburdening of the soul by sharing with others an intense coming of age. Thank you, I feel privileged to have experienced this view into your personal past experiences.

ESSAYONS

Glenn.

Thanks so much Glenn…and that describes the laying down of the story through all of the books.

We are closing on the end of the combat phase of my life and will soon move into the revovery when I start publishing

The Cowardly Lion…which I had to become when I came back into the ‘real’ world to survive.

Semper fi,

Jim

“Cowardly Lion” is now on my must read list. Thanks for the heads up.

It will be a while…

But stay with me, Glenn

Semper fi,

Jim

Prayers for your surgery to go well & a speedy recovery.🙏

Thank you, Cathy.

Heading to the hospital today.

Semper fi,

Jim

Good luck with the surgery LT

Thanks for that. The guys and gals pulling for me have true meaning in my life now.

I can hack it. I’ll just draw on Junior’s survival instincts!

Semper fi,

Jim

Prayer for everything to go well on your surgery and speedy recovery Lt.

Chuck filling in for Jim, Richard.

The surgery went well and Jim should be out in ICU Sunday.

Thank you for your support

Prayers for a successful surgery and a full recovery!

Chuck filling in for Jim.

As I mentioned before surgery was a success.

He will probably be moved to regular room Sunday.

He will be reading all of these well wishes.

Thank you

Let, my thoughts go with you. Looking forward to your return to duty

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

Father in the name of Jesus, I lift James up to you. I ask for a totally successful surgery and complete recovery.

Amen

Thank you, Ricky,

Semper fi

Jim

Nice, my pray too!

Be well Brother. I had a small heart attack about three weeks ago, The pain was tremendous. I laid on the floor with my feet and lower legs up in a chair. I said a little prayer, if you can call it that. Ö.K. God don’t fuck with me. Do or do not. Went to sleep, believe it or not, and woke up in the morning. He didn’t. Went to the Doc the next week. He said I have a left bundle block an another artifact”he can not I.D. They got me on meds. This gittn old shit sucks.

see ya on the other side of the grinder. Still, lookin forward to sippin a beer with ya.

Looking forward to the ‘beer time’, Bud.

Hope your condition improves

Semper fi,

Jim

Good luck with your surgery. You will be in my thoughts and prayers. I have been with you since day 1 and it has been both exhilarating and freighting. Eagerly awaiting the next installment.

Thanks for your thoughts, Patrick.

I ‘squeezed’ out another installment last night and it will be published today.

Semper fi,

Jim

Godspeed for your successful surgery and recovery cousin. Will see you soon!

Thanks for your kind thoughts, Savanna.

On my way to Chicago this morning for Prep.

Thank you for taking the time to answer. I know my first time I was pretty much a duvus. The second time I cracked a joke just before they scrambled all hands on deck. I think the joke was to a very sweet nurse who I know now knew trouble was brewing. But she laughed anyway after asking me how I was doing and I responded very inappropriately that I would rather have a yeast infection. Smiles will get you about anything you want or need just start early as you can and you’ll be fine. Sempre Fi

I am so thankful for your support, Poppa J, and of course your sense of humor.

Semper fi,

Jim

Your health is # one , good luck and God’s speed for recovery. Can’t wait for the last book to be printed so I can start all over from day one since I have a bad case of CRS.

The last segment came out yesterday and the next one after that tomorrow, so I am punching them out just before I go under.

Thanks for the kind words. Five more segments, or so, to go and the third book will be done, before the follow on book.

Semper fi,

Jim

Another great read! Thank you and prayers for a full recovery.

Thanks Ray, means a lot to me, the well wishes and all, not to mention the compliment straight from the shoulder.

Semper fi,

Jim

Praying for a speedy recovery from ur surgery. And again II. Just blown away with your writing. Fantastic job.

Thank you, Billy

Semper fi,

Jim

LT, another great read. Good luck with the upcoming surgery. I will offer more prayers for you and a speedy recovery.

Jim

Thanks James, I shall endeavor to persevere through this. The last segment came out yesterday and the next one tomorrow.

Wanted to get ready for the end and also give you guys something to hold on to until I am back.

Semper fi,

Jim

Glad you are back and in cardiology rehab! I eagerly await the outcome of Ferry Cross the Mersey.

I am not in rehab. The operation was delayed until Wednesday so I hope I will be in rebar after that.

Thanks for caring and saying so on here…

Semper fi,

Jim

James, may the doctors operating on you be guided by the the Holy Spirit Himself. May He give them wisdom and skills.

Para 18 or so, “ordinance?”

right below the music play bar thing:

distribute the man accordingly. Maybe “the men?”

There’s something else, but I can’t find it now.

Thanks a lot Tom for being an editor here. Sure does help.

Semper fi,

Jim

James, thanks for another great chapter. Good luck with the surgery.

thanks for the well wishes and the compliment Mike. I am ready to go in on the 22nd.

Life’s adventures…

Semper fi,

Jim

I don’t see any comments?

What are you talking about Tom? Oh, you don’t see them until I answer. I am on it this night.

Semper fi,

Jim

Thx Jim. I didn’t know about that. Don’t recall running across it before.

Thanks Tom, appreciate the help and the concern too…

Semper fi,

Jim

Another excellent read. Prayers your heart surgery is successful. Looking forward to having all three books.

Yes, only about five segments left after the next one hits on Wednesday.

Thanks for sticking with me so loyally.

Semper fi,

Jim

Still here, since Day 1 Sir. I don’t know even after two separate readings if I am just too emotionally attached but I could not find any serious needs for editing. You keep banging away at a readers 5 senses, which is crucial with your chosen approach to retelling this tragic, yet heroic event in the lives of your now TWO companies of Marines. As we near the end of your tour I just want to say it has been an honor to follow you day by day. Thank you for sharing this defining segment of your lives, along with all those you lead. With you through the end.

Thanks so much for the depth and sincerity of your comment Bob, particularly at this rather sensitive time.

Much appreciated and the compliments too.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great read. Prayers coming your way for successful operation and recovery.

Appreciate that, Frank

Semper fi,

Jim

Good luck with your surgery & thank you for another great chapter.

Thanks, Phil.

More coming soon

Semper fi,

Jim

Get well soon —- you are needed and appreciated!!

I am honored to have the support of such a fabulous group.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great segment once again. You will be in our thoughts and prayers as you fight your next battle. Had a quadruple bypass at the end of last October 2018 and was back to work full time end of January 2019. You will fare well I am sure. Important thing is to stay positive.

Yes, thanks Tom, although I cannot imagine that I can pull away from everything for that long.

My weekly newspaper needs me and so does the writing, but God makes those rules and I shall endeavor to follow them.

Semper fi,

Jim

Lt. This has got to be really tough to write, day 29 and in two more days your heart surgery. I hope and pray that you doctor’s have a steady hand. That your recovery will be easy, and you are back to being a new man soon. I will await the next up date when you are ready. Until then I and everyone else here wish you God’s speed.

Thanks so much SGT. I will be ready and raring to go when they are done, or so I hope. Thanks for the kind words and yes, right here right now and I have to continue

to the end? Well, yes, as a matter of fact. God’s rules, not my own.

Semper fi,

Jim

Knowing the end is near I am on pins and needles to read the rest. Then I will buy the last book. Thanks, LT. A very good read.

I will finish soon, God willing and this heart thing lets me recover quickly.

Thanks for the kind words and the compliment inherent in your writing.

Semper fi,

Jim

Wishing you the best and a speedy recovery from successful heart surgery.

Thanks, Walter,

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, I too will be going in for an aortic valve replacement two weeks from today. I hope I’m around to see the final chapters. It’s been good therapy for an old DUSTOFF medic to see the war from another perspective. I was always looking down on you guys and now I have just an inkling of the hell that y’all went thru. Good luck with your surgery. If neither of us survive, I’ll see you on the other side….P.S. bring a copy of the final chapters!! Hahaha!!

‘see you on the other side,’ I love that, old Mountain Man expression.

Thanks for the kind words and the good thoughts and putting a smile on my face this night.

The next segment will come out tomorrow.

Semper fi,

Jim

Take care of yourself first and worry about finishing the book when your feeling better

I appreciate your thoughts, Roger.

Semper fi,

Jim

The old guys who used to roam this country in the badlands and forests used to use that language. The Mountain Men. See you on the other side.

Neat expression. I will have the books in my head, where they remain so you will get the end one way or the other.

Semper fi, and thanks a lot for making me smile.

Jim

James, this is an outstanding chapter. Good to see you writing, and best of luck with the hospital thing.

Facing one’s own mortality. You know, I think most sentient people rarely get that chance. For those of us who HAVE, life can sure throw some crazy curves.

Your “crossing the Mersey” is going to be one Hell of an expedition, but you seem to have the Marines dialed in for the task. I will try to be patient until you can get the jaunt down on paper.

Semper Fi, my friend.

The next segment comes out tomorrow and then the last five when I get out of the hospital, hopefully sometime next week.

Thanks for the great words in your comment and the meaning that shines right on through.

Semper fi,

Jim

Intriguing as usual Jim

I was wondering what happened to you Lieutenant. I hope you are well and are on the was to a speedy recovery. Another wonderful chapter. I hope this plan works out. Can’t wait to see.

One small edit. Paragraph #9 , last sentence , should be “remaining” two companiew crossed to thee other side.

Thanks, Gunny.

Corrected the error.

Your eyes were very helpful.

Semper fi,

‘Jim

Prayers for you. We readers can wait.

Nah, you can’t wait! So I wrote another segment today and it will go up tomorrow, to tide you over.

Thanks for writing what your wrote on here and your serious concern.

Semper fi,

Jim

Heal up our friend. We need you to finish your story. What a chain of events that follow us in combat. Be well and remember the next chapters.

Next segment tomorrow Marlin, and thanks for the patience and sticking with me through this new odyssey.

Semper fi,

Jim

The intensity is mounting as Sugar Daddy and others are no longer in position to make the plan come together. There is so much on the line one more time. With the heavy losses will they be sending new recruits . As the saying goes “ truth is stranger than fiction. My cardiologist is on stand by for tonight’s encounter. Thanks LT for your writing.

Thanks W. Sapp. I like the cardiologist thing. I never had one of those before but I sure do now. Three, in fact.

The next segment comes out tomorrow so there will be ruminations while I wait out the time they say I have to wait out

for recovery.

Semper fi,

Jim

Extremely difficult situation that you all were in that the NVA were too damn confident to realize you weren’t going to stay there and be overwhelmed by them come nightfall.

I had self propelled 155’s and 8” located on the end of the airstrip in An Hoa and Hill 55 got hit hard while there.

Thank you James, and praying for success and good health from your upcoming heart surgery- Semper Fi brother!!

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

That should have been Fusner Damn auto correct

I continue to be amazed at the resilience displayed by you and your men. You are one of a kind, yet one of a long line of American fighting men who give better than they get, and have done so since the American Revolution, or before.

My mind may be going, but I don’t recall your brother being mentioned before. I lost the essence of my brother in RVN. He survived, but yet he didn’t. Still suffering 50 years later.

May your surgery and recovery go well!

Possible edits: “The NVA had shown no resistance at all make that “reluctance” ??

“… this next night might be our last unless we get across the river, hold up under the cliff, …” perhaps “hole up under the cliff..” ??

thanks for the great comment Mike and the editorial help. No, I had not mentioned my brother being in combat at the same time as me over there.

We did not know that brothers did not have to serve in the same conflict but you had to tell the military that. They did not volunteer that information.

Thanks for the concern. My brother passed although not until after I was hit myself, but I won’t be writing that in the story because it hadn’t happened yet.

Thanks for the care and the concern and the help.

Semper fi,

Jim

I hope Fisher passed along Ferry Cross the Mersey and added get even for Sugar Daddy on his jungle Telegraph.

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

I know the question has ben asked before, but will the three volume set include a map or illustration of the movements during your time in the valley? Sometimes it’s hard to visualize the all the ground you’ve covered. Thanks again for your story.

Yes, the three volume set will include a may and plenty of illustrations and unit descriptions.

There will also be a huge single volume that will have that data and cartography in it.

Semper fi,

Jim

You have yourself squared away for Wednesday. The crew working on you and your problem are well exercised in the delicate work of repairing your living heart. After, when you can complain do so if you need to. And if anyone asks you if you have pain say yes particularly if you get the word they’re about to remove some tubes or wires. And as everything proceeds normally they will be detaching more and more restraints and will be helped into a chair bedside. There starts the journey. We pray for you the whole time. And we know The LT can grunt his way to full recovery. God bless

Oh, and this is one helluva plan. Your Marines are about to make it work, we sense it because they have done so , many times before. Poppa

Thanks Poppa, you guys have given me a great gift in life. I have come to believe that I was a pretty good commanding officer after all under the circumstances.

There was no quit in me then and now. I should not have survived the wounds I received but they said at 1st Med that I had a survivors body. I’m counting on that now.

I can hack the pain and getting through to rehab…but its sure a helluva lot better and easier with guys like you riding shotgun for me…

Semper fi, my true friend,

Jim

Recoup from surgery Lt. never knew about brother sorry. Many of us had s*** sandwich there. We came back to tell our stories. Warriors one and all. Thanks to you and those like you most of us came back. Love to all our brothers.

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

All I can say is “damn Lt” great writing as usual!

Thanks, Brian.

The support of the readers is very heartening.

Semper fi,

Jim

My prayers are with you as you have surgery, L.T. I’d tell you to take it easy as you recover, but somehow I don’t believe that you’re a ‘Take it easy’ kind of guy!

Semper Fi!

Chuck filling in for JR.

According to his daughter, all went well with surgery but he is driving the staff ni=uts

good luck on your upcoming heart procedure LT—had mine four years ago–a quad bypass–they can do miracles today—am up and totally functional—thoughts and prayers are with you and your family as you face this surgery—if an old Navy LT

can get thru it you as a tough Marine should have no problem—demand cute and caring young nurses–they make this journey easier

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

we were never there 63-67

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

Incredible story and story teller ! Would make an incredible movie

Best wishes for your upcoming medical event and recovery.

Semper Fi!

Semper fi

Thanks, Bob,

Semper fi back to you,

Jim

Saw the update last night just before going to bed – wisely made the decision to get up early this morning to read.

“If I lasted through the years I wondered how I would come to consider the man or any of the Marines around me, and still alive. Humanity was a term that could only be applied loosely to any of us” The return to the world, (civilized society) thankfully, for most of us, slowly whittles away at our warrior shields and responses.

” it was impossible for me to believe that I could survive another year under such conditions” It’s impossible to explain to others, that when you get to that level of acceptance, how liberating it is. You never, ever, give up on trying to save as many of the company as is possible.

“I’d come late to discover that I, inadvertently, had built the confidence of the Marines around to such an extent that they had gone from being ‘dead men walking’ to believers that they might make it through the Vietnam war experience and one day go home without serious disfigurement or injury. I had, however, not built up that belief system inside myself.” – Leadership = but your expectations of yourself exceed those of your men.

I was sent to Yokosuka.

Thanks so much for helping so many of us with the healing process – but now maybe it’s time for you to focus on the upcoming surgery. Best wishes for a speedy, successful recovery.

Your comments are always so appreciated, Bob.

Heading to Chi-town for prep.

I will be back ASAP.

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim thanks for another great segment.You are a great leader of men and a great writer.Your Thirty day’s should be required reading for all officers in training could save thousands of lives .Hope all goes well with your surgery.Once again thanks for your service and sharing this great story!

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

Welcome back. Another great chapter.

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

I know the same feeling’s you have went through , God bless you , you have earned it !

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

The suspense is building!

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

You do what you gotta do LT. HQ. not always right !!!

“My baby wrote me a letter” surreal or what?

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

All too often, I’ll be reminded. Reminded of the importance held within the sounds and songs of the mid to late sixties and the role they’d play in weaving the fabric of both life and death for so many of us, living and dying during that time. Those songs represent for me the transition from 1967 to 1968. As an about to be eleven year old kid, the shift from my own idyllic world perceptions to a more frank if not less sheltered view of reality. A shift that might come by way of clever teachers who’d open their pupil ‘ s eyes by way of songs either played or performed in the classroom, or on the radio. In any case, that time required interpretation and guidance. I believe the Gunny was right to question “Ferry Cross the Mersey” because musically it was after all, a hopeful croon against impending loss. Though perhaps, a bit over-produced! In stark contrast to Fusner turning on his radio in time to hear “The Letter”. A song which was described by my teacher in our fifth grade classroom as “akin to the Vietnam war…no more than a wistful plea to a return…completely lost on powers that be, and in the face of a rapidly growing, and for too long ongoing, situation of impending tumult, turmoil, and doom.”

When reality bites, whether young or old…it never let’s go!

This chapter was for me, the most expressive you’ve written thus far of the unfathomable depths of sadness experienced in the reality of combat. Even as you steadfastly refuse to go down! You and all our brothers in arms have my undying respect. Tremendous work, sir! Carry on!

Semper fi,

ddh

What can anybody say about how deeply you seem to be the drummer to the rock group I am sending out the message from in front of….

James, You never cease to amaze me with your novel plans. At least now there is some hope. I await what unfolds.

Some minor editing suggestions follow:

Supporting artillery fire could reach up to, across, and deep past that rim, but not accurately, once the 175 rounds were fired they did not have the arc to go over or to one side or the other of Hill 975.

Seems like two sentences. Maybe period after “accurately”

Supporting artillery fire could reach up to, across, and deep past that rim, but not accurately. Once the 175 rounds were fired they did not have the arc to go over or to one side or the other of Hill 975.

that meant the only way out was either to attack up the valley until reaching either friendly forces or the DMZ itself

The “either” before “to attack” seems extra. No alternative is given for what follows.

that meant the only way out was to attack up the valley until reaching either friendly forces or the DMZ itself

/although later the alternative of crossing the Bong Song is presented/

Medevac instead of Medivac – multiple instances

save the A-6 if it came into bomb the hell of the same jungle it had become accustomed to the bombing.

Maybe change “into” to “in to”

Maybe drop the “the” before “bombing”

save the A-6 if it came in to bomb the hell of the same jungle it had become accustomed to bombing.

the Ontos was moved, and then the remains two companies crossed onto the other side.

Maybe “of the” or “from the” before “two companies”

the Ontos was moved, and then the remains of the two companies crossed onto the other side.

/OR/ the Ontos was moved, and then the remains from the two companies crossed onto the other side.

and I presumed they were orbiting out of contact us to let them know what we were doing

/Not sure exactly how to read this. My guess is they are waiting for you to initiate contact/

and I presumed they were orbiting waiting for us to contact them to let them know what we were doing

and the enemy could be kept sufficiently suppressed to allow the Marines doing to work to survive while they did it.

Maybe change “to” before “work” to “the”

and the enemy could be kept sufficiently suppressed to allow the Marines doing the work to survive while they did it.

I’ll rain a zone fire down into the valley while were climbing out

Change “were” to “we’re

I’ll rain a zone fire down into the valley while we’re climbing out

we have almost four hundred Marines

/number seems high for remains of two companies??/

/Just a minor detail

serving down in Ben Wa

Maybe Bien Hoa. It was the largest town in III Corps – about 20 miles from Saigon. Site of a large airbase. At various times the 173rd Airborne or portions of the 101st Airborne were based there./

May your upcoming medical procedure be uncomplicated and totally successful. May your healing be swift. Blessings & Be Well

As always, Dan, your sharp editorial eyes are so appreciated.

I believe we have corrected all,

Semper fi,

Jim

Flash….Junior…..I prefer Junior. It’s deceptive in a good, sleepy way that that carries a profound sense of unspoken hard earned confidence.

LT, as you close in on the next adventure in your life, please know this, you’ve made my list. It’s not extremely long, but as I age it has slowly increased in length. It’s the list of those individuals for whom I pray on a semi-regular basis. The longer I live the more importance it seems to generate.

I’m grateful to you for sharing in such riveting detail. It keeps alive the memory of family members and friends who have served as far back as Sherman’s March and as recently as Benghazi.

Keep turning the crank. It’s important.

Grace to you always,

Jeffrey

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

Makes me think about “ my short timer” status!!! So short my ass hit the curb. And all the while we were in the country! Wanting to shit in a stateside shitter!

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

Semper Fi,keep em coming.

There are at least two places where you’ve used the word were when you mean we’re.

Thanks, Bob.

I think we got them

Semper fi,

Jim

Jim, Damn. Now you have me in a foxhole, my back against its wall, feeling the vibrations of a not too distant drum, hoping. Hoping that the plans works. Hoping for the re-supply. Hoping for the needed air support is there. Hoping to get the Ontos across to face their next assault. Hoping all those things come together, regardless of BN. Well, here’s to hoping all things come together on the 22nd. Doug

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

It’s been a while Lt….sorry for the lack of comm’s here, been reading all but just not making the comments… you hope to make it out of the A Shau and head for Go Noi Island area.. in the hopes that it will be better than where you are… puts a hell of a perspective into play for those that fought at both places…..Go Noi island….a bad motor scooter all by itself.. thought I lost my leg there once….spun me like a top and threw me down hard…saw a chunk of steel imbedded in the hard bone center below the knee cap…pulled it out and said to myself hell…that’s number three…then my Lt came out of the brush in front of me….nice guy…with no left hand any more….a look of bewilderment on his face…I tossed the scrap of steel into the brush…fuk it….I can still shoot….. you have the advantage of having a “plan”…a goal…a map to look at…the mud Marines just wait….wait for the order to move out..and in what direction…..their only ‘goal’ is to see one more sunrise…..beat the drum slowly…and play the fife lowly….semper fi…

Beat the drum slowly and play the fife lowly..God, but you hit that right on the head of this three ‘novel’ series Larry….

I am here trying to recover…

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

I thought it was “Gary and the Pacemakers” ???

Actually Gerry and the Pacemakers.

Thanks.

Semper fi

Jim

I hate to see this come to an end soon.

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

James, well written. Saw no editing problems whatsoever. Sorry about the 27.

Best of luck in your upcoming operation.

What is the model name of that RV truck thing you are driving throughout the Rendezvous2020. Hope to see it and you when you come down I25 in Southern Colorado.

Best, Dave

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

On and on and on. I can hardly imagine how you keep at it day after day, night after night. Battle after battle. But then you are Marines. And I know you have no choice but to stay the course. I am in awe of your strength a d that of your men.

I am just getting fully ambulatory after the bypass surgery. Sitting at the computer fully erect is still demanding but I am getting stronger day by day. Wednesday of this week (Feb 5) will make it two weeks.

Thanks for the comment and I’ll be fully answering all my comments again soon and also finishing the Third Ten Days. My heart surgery was a success but the recovery will be a bit longer than I

anticipated.

If you want to help you can buy my books (there are now seven available) either online or if you want autographed and signed/inscribed from my website here. If you can and want to help with the coming

jamboree this year and tour then you can contribute at https://www.gofundme.com/f/thirty-days-has-september. I will much appreciate whatever attention you pay to me and my work.

Semper fi, and I cannot thank you enough.

Jim

Great read ,, couple or Qs …”hell of the same jungle it had become accustomed to (the??)

bombing.“

“ If I lasted through the years I wondered how I would come to consider the man or any of the Marines around me, and still (??alive.??). Live??

“I could hear the Skyraiders orbiting high above, and I presumed they were orbiting out of contact (?? Waiting for us??) to let them know what we were doing and for the light to improve. “

Thanks

Thanks for the notice, Jim

I believe now corrected.

Semper fi,

Jim

Welcome back LT. More importantly welcome home.