ZACK

Short Story

By J. Strauss

Zack prepared himself for the confrontation. Winter had been hard. So very hard. He hadn’t really been ready for that kind of cold. He’d thought he was ready, but it was the wind off that lake that nearly did him in. He’d been saved by the boathouse. But everything was over. The owner of the big house up at the end of the old runway, which led directly down to the boathouse, had come back early. Zack looked over at the electric barbecue grill, which had kept the small space, occupied by himself, the cat and a wooden Streblo boat, warm.

The cat, a feral gray thing, drifted in right after Christmas. One morning Zack awakened to the loud cracking sounds of thick lake ice breaking up and discovered a heavy weight atop his chest. He opened his eyes, terrified. Two hazel eyes stared into his own, inches away, unblinking. It had taken many moments to generate enough courage to move. The cat, however, did not hurt him. Instead it leaped away and disappeared, not to reappear until Zack was once again asleep.

The cat, a feral gray thing, drifted in right after Christmas. One morning Zack awakened to the loud cracking sounds of thick lake ice breaking up and discovered a heavy weight atop his chest. He opened his eyes, terrified. Two hazel eyes stared into his own, inches away, unblinking. It had taken many moments to generate enough courage to move. The cat, however, did not hurt him. Instead it leaped away and disappeared, not to reappear until Zack was once again asleep.

A week passed before they confronted one another directly, and then come to terms. Zack fed the thing, let it sleep on him, and was allowed no closer than three feet from it at other times. In return, Zack got nothing. Except company. And that was enough.

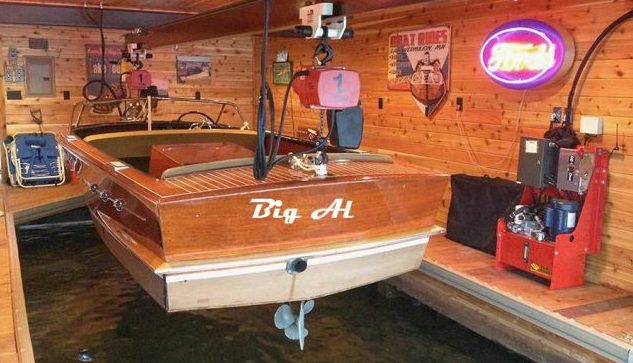

The wooden boat had the name ‘Big Al’ on it’s stern. Streblo was inset along the side of its hull in small metal letters. Zack liked the manufacturer’s name, although he thought it a dumb name for a boat. So the cat became Streblo too.

“We’ve got to go Streblo,” he said.

Streblo regarded the eight-year-old boy, from his place draped over the bow of the boat, one paw and his tail hanging over each side. The tail flicked back and forth every few seconds.

“Well, I have to go anyway. That man up there is waiting. I can’t cross the lake. The ice broke up. I can’t go along either shore. It’s too open. Too open for a runaway.” The boy took a break from gathering his small canvas pack of goods to peak through one of the windows facing up toward the big house. A huge man sat on a chair at the top of the lawn, staring down the brown grass runway. The man had approached moments earlier, knocked on his own boathouse door, and then yelled through it. His instructions had been clear. Whoever was in the boathouse could get his or her things together and be up at the main house in half an hour or the police would be coming.

Zack didn’t have a watch, but he knew how long half an hour was. He delayed the coming confrontation because of the heat. He would miss the heated space. He’d miss the storehouse of canned foods he’d yet to go through completely (the canned chicken soup was his favorite). He’d miss the tiny but personal bathroom, but most of all he’d miss the cat.

He put his pack on, adjusting the straps. The pack was heavy because it was topped off with a load of stolen sardines and crackers, which were Zack’s favorites after the soup. That the boathouse had been stocked with canned goods had been a winter lifesaver. Zack squared his small shoulders, leaned to balance the pack, and then turned to approach the cat. Amazingly, the animal didn’t shy away when Zack breached the limiting three-foot perimeter. Zack held out his left hand. Streblo sniffed it. One brief pat on top of the head was allowed before the animal disappeared under the blocked-up boat. Zack smiled to himself, staring down in surprise at his uninjured hand.

“You take care, Streblo,” he murmured out into the remaining space of the boathouse, before going to the door and stepping outside. Slowly and carefully, he closed it behind him, once again wondering about how the cat got in and out without using the door. It was an unsolved mystery. Zack had been up and down the Eastern side of the lake early in the winter, checking out boathouses. He’d found just about everything imaginable but never another cat. Most animals did not do well in weather colder than five degrees. It had much colder than that through most of the hard winter.

The dead grass of the old unused runway was wet and soggy. The incline was gentle but steady, so Zack was breathing heavily when he walked up to the huge sitting man. He had to take his pack off to rest. He made a big deal about unstrapping the thing, more to hide his nervousness than because he was tired. The big man said nothing. Zack noted his calm face, totally devoid of expression. He knew that that was not good. Finally he readied himself by straightening his thin body and throwing his small shoulders back.

“How old are you?” the man asked, his eyes slitting slightly as he got out the question. Zack stared into twin black pools. He knew that his usual lies were not going to work on the man.

“I’m sorry, I don’t have that number for you right now,” he answered, in as flat a tone as the man had used to ask the question.

The man brought one large hand up to massage his jaw. Several seconds passed. Neither the man nor the boy blinked during their passage.

“I don’t believe I’ve ever heard that answer before,” the man said, his voice evidencing disbelief. “And I thought I’d heard it all,” he went on. “I’m an attorney. A great attorney, for Christ’s sake, and some little kid waltzes up and gives me an answer I’ve never heard before. I don’t have that number available right now? Wow!” The man’s hand dropped back to his side.

“Who the hell are you, anyway?” the attorney inquired.

“My name is Zack, and I’m no little kid,” Zack responded.

“Well, I take that back then,” the big man said. “So you’re a minor runaway with an invented name. Why Zack?” he asked.

“What’s your name?” Zack countered, then added, after a small delay “Sir.”

I’ll ask the questions here,” the big man responded instantly. “You’re trespassing on private property and doing I don’t know how much damage to my boathouse.”

Zack said nothing. He could not keep from staring straight into the big man’s hypnotic eyes.

“Jerry. Name’s Jerry,” the attorney finally answered. And this house used to belong to the governor. He died so I got hold of it.” The man glanced behind him, as if to assure himself that the house was his and still there.

“I can’t call you Jerry, sir,” Zack said.

“Why not? Oh, I get it. You have manners. Common burglar living off my land for nothing, but having high-class manners. I don’t believe it. Strain. Mr. Strain, like in a strained knee. You can call me Mr. Strain.”

“Why do you weigh so much?” Zack asked.

“Well you little…” the big man began, then sighed deeply before going on. “I’ve lost sixty pounds. I used to be fat. Now I’m just hefty.”

“Like the bag?” Zack asked.

The big man started to laugh. “Joey Bishop never had such a straight face,” he got out between laughs. “Hefty bag. I’ve gotta tell my wife that one. In the mean time, what am I going to do with you?”

“I’ll just go home on my own,” Zack stated, hopefully.

“I wonder how long you’ve been down there,” Mr. Strain mused, his voice barely audible. “All winter? And what kind of price does that portend?”

“Portend?” Zack asked, blinking his eyes a few times.

“Doesn’t matter,” the attorney waved his ‘hefty’ hand. “What matters is what happens to you. What do you want? You want go home to a home you don’t have? You want to run to somewhere else until it warms up? Or you want to stay in the boathouse for awhile longer?” He stared at Zack when he was finished, with his cold black eyes. Unblinking. Waiting.

Zack tried to think deeply about what he’d heard. He couldn’t believe that the man might be giving him a chance to stay. Adults did not give things away for nothing, he’d observed during his hard eight years.

“What in hell is that?” Jerry said, pointing his finger toward the lake.

Zack whipped around. A gray object raced toward him, jinking right, then left, before arriving to crouch next to him. The cat had stopped just over three feet from the boy, his normal distance of comfort, but his eyes were riveted on the attorney.

“That’s Streblo, my cat,” Zack said, acting as if the wild animal was his domestic pet.

“Streblo? You named that mangy thing Streblo? After my expensive boat?” the attorney asked, in disbelief.

“Big Al’s a bad name,” Zack answered as best he could, hoping that Streblo would not attack or do something dumb. Any chance of staying in the boathouse might, if it was real, disappear if the man felt any slight at all. Adults could not be depended upon.

“Don’t tell my wife,” Mr. Strain said. “Big Al was her Dad. It was his boat. Now hers. I don’t know about that cat. He doesn’t look like anybody’s anything, but if you want him then he’s all yours.”

Zack almost said thank you, but stopped himself. Nobody owned Streblo, so the cat wasn’t Mr. Strain’s to give away. Zack had been around. Adults constantly gave away stuff that wasn’t theirs, but hung on dearly to anything that was.

“You want to stay in that boathouse until we come up for the summer? Well, you gotta do something for me,” Mr. Strain stated, his right index finger turned inward to point at his own chest.

“What do you want?” the boy asked, his voice guarded.

“Hell, I don’t know. I’m bored. Stuck in this goddamned inherited resort for the weekend. You come up with something. I’ll be in the house later, drinking fine Malbec wine. When you think of something, knock. If you don’t then goodbye, to you and that feral fellow traveler of yours,” the attorney finished talking. He rose slowly from his chair.

“C’mon,” whispered Zack to the cat, grabbing his pack with both hands, and then turning to run back down the overgrown airstrip.

“Surprise me,” the big man yelled after him, “nobody surprises me anymore,” he said, his voice beginning to fade behind the running boy, “I’m sorry, I don’t have that number for you,” was the last thing Zack heard before he got out of range.

Streblo reclaimed his spot across the bow of the wooden boat. Zack broke open a can of Campbell’s soup. He ate it cold, tossing the noodles down by tipping the can up and tapping the bottom with his fingers, once the yellow liquid was gone.

“I think that’s the strangest man I’ve ever met, Streblo,” Zack said up to the sprawling cat. He opened a can of sardines, and then placed it carefully up by the animals paw. Streblo just looked at him.

“I know, you’ll get it later,” the boy said wistfully, “It’d kill you to actually accept something when I gave it to you.” Streblo’s tail swept down once, before returning to the top of the boat. The boy sighed.

Zack peered out the side window of the boathouse. He had to think. What could the big unhappy man living in the big unhappy house possibly want? He tried to look around a concrete statue to see more of the broken lake ice. Then his eyes were drawn back to the statue. The thing was bigger than a human, except it lacked a head. Only the body, in flowing stone robes, stood facing out toward the lake.

Something nagged at the edges of the boy’s mind.

“I think I have it,” he yelled so excitedly that Streblo jumped up to all fours, before settling down again to sit and eat sardines straight from the open tin.

Zack hurriedly emptied his pack, then immediately raced to the boathouse door and was gone. Dragging the empty pack with one hand he ran a distance four boathouses down the lake. When he got there he stopped behind some pines to wait. Slowly he checked out the entire area for movement, but there was none. He approached the boathouse. The door was closed, just as he had left it a week before.

Zack turned the knob. The door was still unlocked. Once inside he searched the shelves until he found the big yellow pail he’d remembered. Pulling it from the low shelf he set it on the concrete floor and removed its contents. Inside the pail was a large stone head. Carefully, the boy placed the object into his pack, and then returned the pail where he’d found it.

The head was heavy. Zack had to strap the pack to his back. He could not run with the weight so he walked bent over all the way back to the statue. He looked up at the headless figure. He knew that he wasn’t strong enough to put the head back up on it. Even if he could, he realized, he had no way to make it stay.

Part of the boathouse stuck out into the lake. It was the part that some service would come along and erect a wooden pier out from, Zack knew. But it was still too early in the season for that. At the end of the concrete he removed his pack, then rolled the head out as gently as he could. He set it up on the flat part of the broken neck so it faced the boathouse, then he tossed his pack inside the boathouse door before running all the way back up to the house.

Zack didn’t knock. He saw the big man sitting at a table inside, through the back door glass. The man was drinking his Malbec from a dark bottle, not even using a glass. Zack sighed. He’d seen adults drink like that before and it made him uncomfortable. He went inside, closing the door behind him.

“I have it,” he said to the man, who seemed to take no note of him.

“Have what?” the attorney asked, taking another great swig from the open bottle, dribbling a little rivulet of red down onto his white shirt.

“The surprise,” Zack answered.

“You are one piece of work, you know that boy?” the attorney said, not making the question a question at all. Zack said nothing.

“Well, what is it?” the man asked.

“You gotta come down to the boathouse,” Zack answered, “I mean, if you can.”

“Ha, come down to the boathouse. You think I’m infirm or something. I’m just big, not disabled. C’mon,” Mr. Strain said, as he laboriously rose from his chair.

Zack followed the big waddling man through the house into the attached garage. The man hit a switch and the place lit up, while a garage door started to go up.

“Here we go,” the attorney said, slipping into an electric golf cart. He took up the whole front seat. Gingerly, Zack moved behind him, sitting in the middle of the back seat, but holding on to the sides with both hands. The cart lurched forward. The trip down to the boathouse took only seconds it seemed. The silent cart appeared to float over the dead grass. The cart stopped right beside the door of the boathouse.

“Well?” the big man asked, turning to face the boy.

“Well?” the big man asked, turning to face the boy.

“There, at the end of the stone,” Zack pointed.

The man looked, and then did a double take before removing himself more quickly form the car than Zack would have believed if he had not seen it. The man got to the stone outcrop before Zack.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he breathed, “you found my head.”

Zack stood next to Mr. Strain, but was as shocked as the man was when a fast moving gray object raced by both of them. Adroitly and smoothly, as it the move had been choreographed and practiced many times, Streblo ran out along the concrete, performed a short leap, touched the stone head with two front paws and then returned, running back through the open boathouse door.

The head tumbled into the water with a splash.

“Oh no,” the big man yelled. Zack raced to the end of the concrete, knelt down and peered into the water. The ice had moved out from the nearer shore areas. He could see straight down though the clear flat liquid. The head lay with its face staring back up at him through four feet of water. Zack’s eyes widened.

“It’s you,” he said, transfixed by the head under the water. “It really is your head,” he went on, before turning to look up at the attorney. “Why is it your head?’ he asked the man. Zack watched the man’s features soften for the first time since he’d met him.

“I just liked the idea,” the big man said, looking away.

Zack stared first at the headless statue, then down into the water. He thought about what the man had said, and then turned to look back up at the house.

“The house is the governor’s, even though he’s dead,” Zack intoned. “The boat is your wife’s boat, still with her dad’s name on it. None of this is yours. You put your face on the statue to have something about you.” The words had all come out of him of their own accord. He was as surprised to hear them as the attorney seemed to be.

“No. It wasn’t that. It could not have been that,” the big man said, staring looking out across the lake.

“I’ll jump in the water and get your head,” Zack offered, moving to take off his coat. He was working on taking his shoes off when the man spoke.

“No. Leave it. It kind of looks better down there, don’t you think?”

Zack walked back over to the edge of the concrete to stand next to the big man and look down.

“I like your real head,” Zack said, softly.

“Hmmm. You think so?” the big man said after a moment, still staring. “You, and that mangy cat, can stay in the boathouse as long as you want.”

James, you have talent you don’t even realize you have, Great story!!

Well, thanks Leo. I’m not sure to this day what I have or

don’t have in the way of writing capability because the real world we live in

does not do much to approve of or compliment good work.

Unless it is by themselves, relatives or close friends.

The criticism I get on here and in Amazon credit I take very seriously

because most of it is so detailed and valid.

Thanks for your compliment and putting it up right here…

Semper fi,

Jim

Lt. thanks for your writing I really enjoy it. I have always read a lot when I was a kid in summertime I would walk to town to the library (six mi one way by road less through the woods) to get books to read for the week. When in USMC whatever base I was at I would read everything they had on one thing, in Okinawa I read about the Boer war and other conflicts. I have read every word of 30 days and most comments. The more I read the more I appreciate your way not just with words but the way you tell your story. You have a way with adjectives that only one other writer that I know can even come close to. Your work keeps one wanting more yet is thought provoking. Simper Fi

Thank you Don. That’s a great compliment. I am so happy you are entertained and learning something at the same time.

thanks for coming on here and writing about that too.

Semper fi,

Jim

Great short story. Hanging on for 15 th. night!

Thanks Harold, working away on it, for all of us…

Semper fi,

Jim

James, I really enjoyed this short story. A story doesn’t have to be long in order to be good and to also give the reader food for thought. Thank you for this incredibly smart story. I always look forward to whatever you post on Facebook.

Thanks Lisa. Not everyone would agree with that complimentary assessment, of course.

Thanks for the support and writing about it on here.

Semper fi,

Jim

I have always felt the way Zack does, “Adults are always giving away things that don’t belong to them.”

Thank you for taki g me back 50 years to a time when I actually knew what I was doing.

Now that is really neat Scott, that you would excerpt that comment and then read deeply into it.

Too true. It’s like the question I asked in Catholic grade school that got me into trouble in the sixth grade:

“why was everything already owned when I got here?” Simple, childlike and devastating…

Semper fi, and thank you for writing on here about it,

Jim

James, although Mr. Strauss seems more appropriate, thank you for making me look forward to opening facebook again. Another quality story by far!

Thanks Bruce for allowing my work to ‘reach’ you in that way.

I really appreciate the comment. You can call me Jim or Junior if you prefer.

Semper fi

Jim

Great short story. A lot to think about in this one. It’s begging for a follow on. Many more chapters.

Thanks Vern. The short stories kind of come in between the chapters and books.

I don’t know why. They just pop up…of course there’s a lot of real life in there

that you picked up on…

Semper fi,

Jim

Great story, James. That you share so much is rare in these times. Thanks for the few minutes away from a sometimes harsh reality.

The proverbial leopard. Walt the leopard. He does not change his spots.

Class act all the way. Thanks Walt!

Semper fi,

Jim

James, once again your character development is outstanding. In such a short story, we grow to like Zack and Streblo for their internal fortitude and personality, and both the cat and the boy really demonstrate intelligent and rational thinking.

Our attorney (who WILL be contacting you directly) becomes a living, breathing human. And yep, I have sure found some really good attorneys along the way. Jerry has some baggage, thus helping him to become a better-than-average human.

Keep writing, my friend, but do get back to “30 Days”!

Thanks Craig. The attorney was a real guy living on the lake and the house

was real too. Jerry still carries a lot of baggage but his wife left him and that

seems to have relieved some of it.

Thanks for your care and interest in my other works.

Semper fi,

Jim

Streblo the cat looks identical to my cat,Snuggles.I also have a small dog named Rufus. I am going on 81 years old and restricted a little

by my knees, so they and my wife are my constant companions.Treat them

just like they were our kids. Enjoyed the story, thanks!

Thanks for liking the story Charlie. Harvey is the name of the real cat in the story.

The House and the Attorney are also real, or were at the time.

Appreciate the compliment and taking the time to write about it here.

Semper fi,

Jim

Quite a story but the last is hard to believe. A lawyer with a heart.

Yes, but the guy really does have a heart. The real lawyers name is Jerry and he runs his own firm out of Chicago.

Pity he’s in zoning as I have no needs there. Had a great friend, Peter Wilson, who was a criminal attorney and

he died, unfortunately. Another one of those rare attorneys. Or, is it not in fact, one of those rare humans?

Thanks for the comment Pete, as usual…

Semper fi,

Jim

Enjoyed reading this but I believe I have read it before. Still good and stirs the imagination.

It’s OK to read our stuff often, Marion. ~~smile

Enjoyed this story. Listened to the audio version. Great story and great narration too. Well done. A great team to be sure.

Thank you Bill

Your business seems to be a rewarding one, helping others enjoy their Dogs.

Appreciate your sharing our site with others